Background and Objectives: Specialized medical school educational tracks aim to increase the primary care workforce. The International/Inner-City/Rural Preceptorship (I2CRP) Program is unique in addressing multiple communities, a large cohort and applying the Self Determination Theory framework. This study examined program impact by analyzing the numbers of graduates matched into primary care and practicing in medically underserved communities.

Methods: We compared the match list of I2CRP graduates between 2000 and 2017 (n=204) to non-I2CRP Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine (VCU SOM) graduates (n=3,037). We analyzed the matches into primary care, National Health Service Corps (NHSC) priority specialties, and NHSC priority plus general surgery. We searched a federal database to determine which graduates are practicing in workforce shortage areas.

Results: Many more I2CRP graduates matched to primary care (71.1%), compared to non-I2CRP graduates (38.2%; P<.001). Within primary care, I2CRP graduates matched to family medicine more frequently than non-I2CRP graduates (36.3% vs 8.4%). Eighteen percent of posttraining I2CRP graduates work in rural areas and 41% work in medically underserved areas.

Conclusions: I2CRP graduates are more likely to match to family medicine and primary care. I2CRP curriculum nurtures new medical students’ interest in primary care, and self-determination theory provides a framework to organize the program curriculum. The program’s impact endures as evidenced by participants’ continued work in underserved areas after residency. Increasing support for such programs may help address the primary care physician shortage in medically underserved areas.

There is a critical shortage of primary care physicians. By 2030, physician demand will be greater than supply, and the United States will face a shortage of 43,000 primary care physicians.1 The demand for primary care physicians will continue to increase with population growth, aging, and insurance regulation.2 This shortage is greater in underserved settings. If lack of insurance and access to clinics were addressed for underserved populations, an additional 95,000 physicians would be needed to fill this gap.1

In order to overcome this shortage, it is important to address barriers and to adopt best practices in academic training to expand the pipeline of primary care physicians. Barriers to enter primary care include emotional burnout and concerns about income.3,4 Other factors found to discourage a career in primary care are the ethos of educational institutions and disparaging remarks from hospital colleagues, referred to as aspects of the “hidden curriculum.”4 Factors that predict careers in rural or underserved areas include female gender, older age, early interest in primary care, Peace Corps experience, community service, and rural upbringing.4-9

A critical juncture in the pipeline to increase primary care physicians occurs during medical school. Several schools have educational tracks to promote primary care careers and to enable students to train and practice in medically underserved areas. Among these programs are 4-year longitudinal programs, where approximately 50% of students enter primary care.10-14 Other medical schools provide electives, volunteer experience, and extracurricular or short-term programs to promote primary care careers.15

Recognizing the need to increase primary care physicians in our state and beyond, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine (VCU SOM) started the Inner-City/Rural Preceptorship (ICRP) program in 1998. It was expanded to the International/Inner-City/Rural Preceptorship (I2CRP) in 2010. Until now, the career outcomes and practice locations of I2CRP program graduates have not been systematically assessed. This study describes the outcomes of the I2CRP program, and uses self-determination theory (SDT) as a model of analysis.

Background of International/Inner-City/Rural Preceptorship Program (I2CRP)

Goals of the Program. The ICRP program began in 1998 with support from a Health Resources and Service Administration grant (HRSA, grant #D15PE80054), and expansion to I2CRP was supported by a second HRSA grant (#D56HP10302). The goals of the I2CRP program are to help students develop the knowledge, skills, and attitudes needed to provide high-quality, compassionate care to underserved populations, and to increase the number of primary care physicians in underserved areas. A focus on a single underserved domain may not be sufficient to fully address workforce needs, as has been reaffirmed in subsequent research.6,10 Therefore, the I2CRP program includes rural, inner-city, and international underserved communities to cultivate transferable skills that may be applicable in all three settings.

Conceptual Framework. The VCU SOM I2CRP program aligns with self-determination theory. This theory proposes that an individual’s motivation to learn is driven by fulfilling innate psychological needs including relatedness, autonomy, and competence.16

Relatedness may be defined as feeling like a member of a community or profession.16,17 The I2CRP program provides students with opportunities to engage with underserved communities in both clinical and nonclinical roles, promoting a more holistic connection between professionals, patients, and the communities they serve. The program is a 4-year longitudinal program promoting peer-to-peer relationships, student-to-faculty relationships, and mentorship among trainees and practitioners with common career goals. Curricular experiences foster group identity and a sense of connectedness. With regular meetings, discussions, and didactic sessions, students validate and reinforce their decision to serve medically underserved populations, while cultivating knowledge, skills, and supportive relationships to sustain the vision for future practice in underserved settings.

Autonomy may be defined as choice, volition, or perceived locus of control.17,18 In the I2CRP curriculum, autonomy is supported by enabling the student to control their individual learning experience and make decisions to support their own career goals. Students elect to participate in the I2CRP program despite the significant time demands of medical school. Upon admission to the program, students choose their track of interest—urban, rural, and/or international—and refine their choices to match their evolving career interests and goals.

Finally, competence may be defined as the mastery of desired skills or the perceived ability to bring about desired outcomes in one’s environment.17,18 In the I2CRP curriculum, competence is enhanced through the presentation of frequent, formative feedback. Participants engage with specialized teaching environments in medically underserved settings throughout the 4 years of medical school. The aim is to cultivate a multidimensional perspective on factors impacting the health of individuals and communities, thereby building competency to better understand and address patients’ lived experiences as well as the complex historical and structural issues that impact health equity.

When the core components of SDT—relatedness, autonomy, and competence—are satisfied in the learning environment, motivation and development of social, professional, and personal well-being are promoted.16 This theory is woven into the fabric of the I2CRP program and provides a framework to assess the program’s structure and content.

Admissions. Admission to I2CRP is based on an application cycle in fall of the M-1 year. The application assesses prior personal and service experiences with underserved communities, interest in primary care careers, and the role students perceive I2CRP may play in their professional development. The VCU SOM class size ranged from 172 to 216 students per cohort for classes of 2000-2017. Currently, the I2CRP program admits 24 students per cohort, and twice as many applicants as available seats typically seek admission to the program.

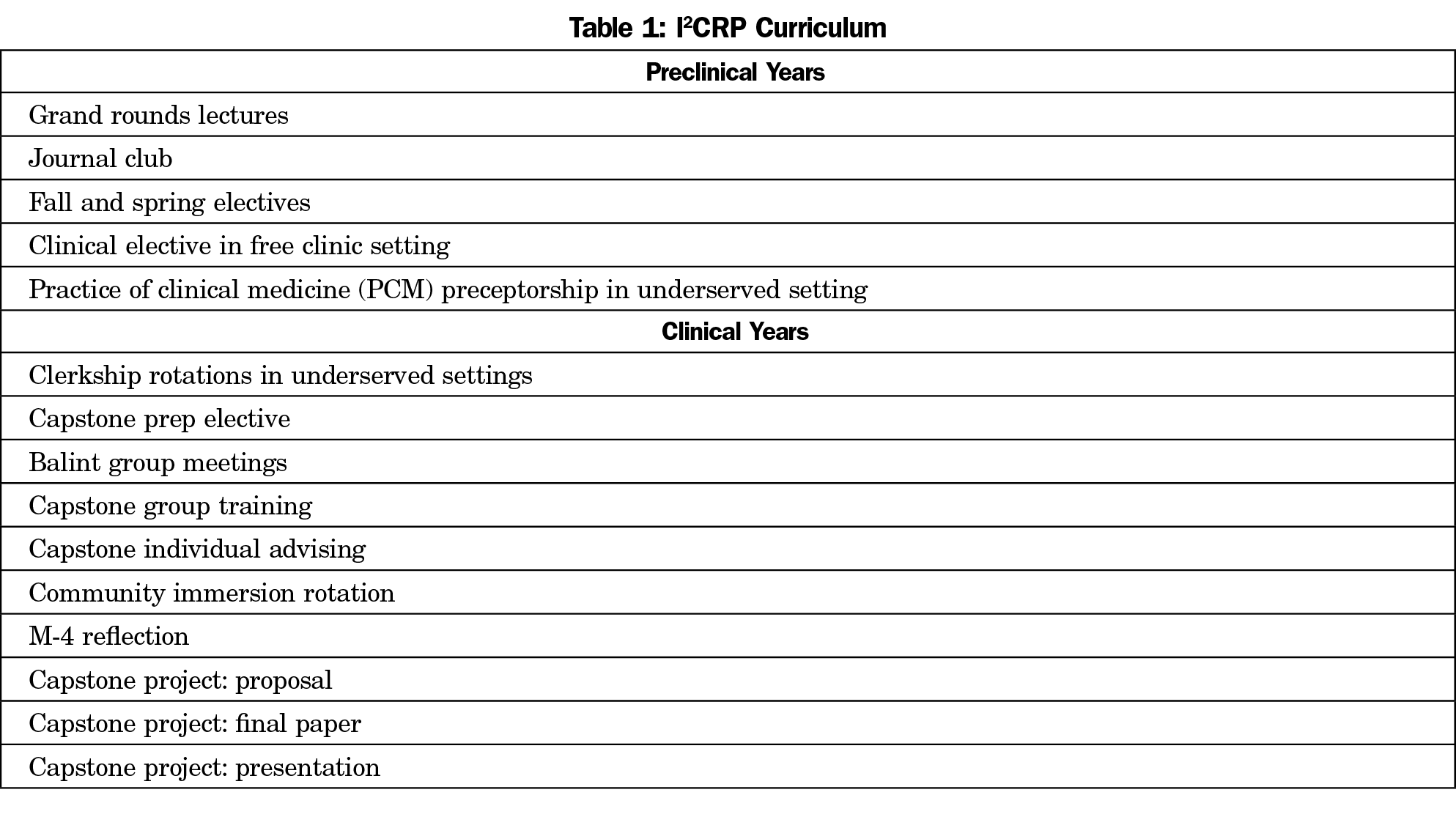

Preclinical. The I2CRP curriculum is divided into preclinical and clinical components. Table 1 provides an overview of the I2CRP curriculum. In preclinical years, workshops and experiential learning activities allow students to explore issues such as social determinants of health and health care disparities, to engage and work with communities, and to understand the impact of policy decisions and structural inequality on the health of individuals and communities. Small group sessions allow topics to be explored in more depth, with opportunities to share prior experiences. Partnerships with community organizations provide a better understanding of local communities and contemporary outcomes of historical policy and political decisions. For their introduction to clinical medicine, students work with physicians practicing in medically underserved communities, where they gain mentorship and opportunities for role modeling.

Clinical. In the M-3 year, students complete up to 12 weeks of clerkship rotations in settings such as free clinics, federally qualified community health centers, academic practices, and private practices in rural and urban settings in or near Virginia, and one site in the Dominican Republic. Rotations include 4 weeks of family medicine, 4 weeks of ambulatory medicine (general internal medicine or family medicine), 2 weeks of general pediatrics, and when possible, 2 weeks of general surgery. Duration of these rotations are equal to the rotations of non-I2CRP students however, I2CRP rotations optimize students’ exposure to primary care in community-based, underserved settings as most non-I2CRP rotations occur within an academic health system. Throughout the year, students participate in Balint groups for structured reflection and debriefing to improve health outcomes by optimizing the doctor-patient relationship.19

The M-4 requirements include a community immersion month and a capstone project. The immersion month may be clinical or nonclinical, and the goal of this rotation is for students to better understand the role of a health care provider in a medically underserved community. The capstone project builds on the model of scholarship defined by Boyer and Glassick.20,21

For the capstone project, students identify a question and a community of interest to define, develop, and carry out a project with faculty and community mentors. Students have formal capstone training sessions during the M-3 year and individual advising sessions with core I2CRP faculty throughout M-3 and M-4 years.

Longitudinal Peer Community. Throughout the preclinical and clinical years, I2CRP journal club and grand rounds introduce skills of critical appraisal of peer-reviewed literature, while integrating scholarly research into discussions on improving the health of underserved communities. Written reflections are used to assess participants’ beliefs and abilities as they continue their professional development. The I2CRP program culminates with M-4 students presenting their capstone projects in poster or oral presentations.

To date, we have not studied outcomes data. The purpose of this project is to evaluate I2CRP’s impact on its participants’ choice of specialties and practice locations posttraining. We hypothesize that I2CRP program graduates are more likely to match into primary care specialties and practice in medically underserved areas compared to non-I2CRP graduates.

Program Evaluation

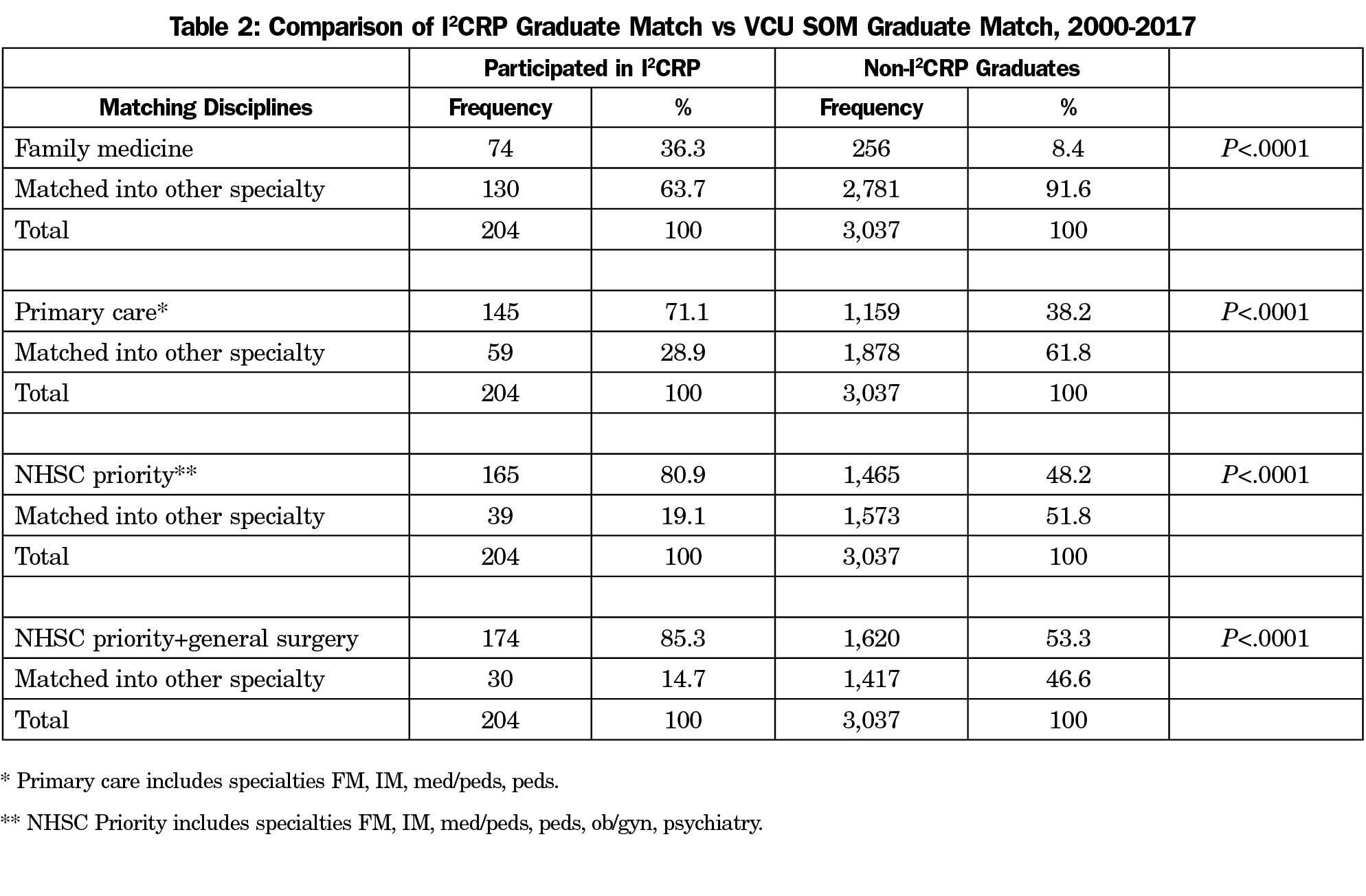

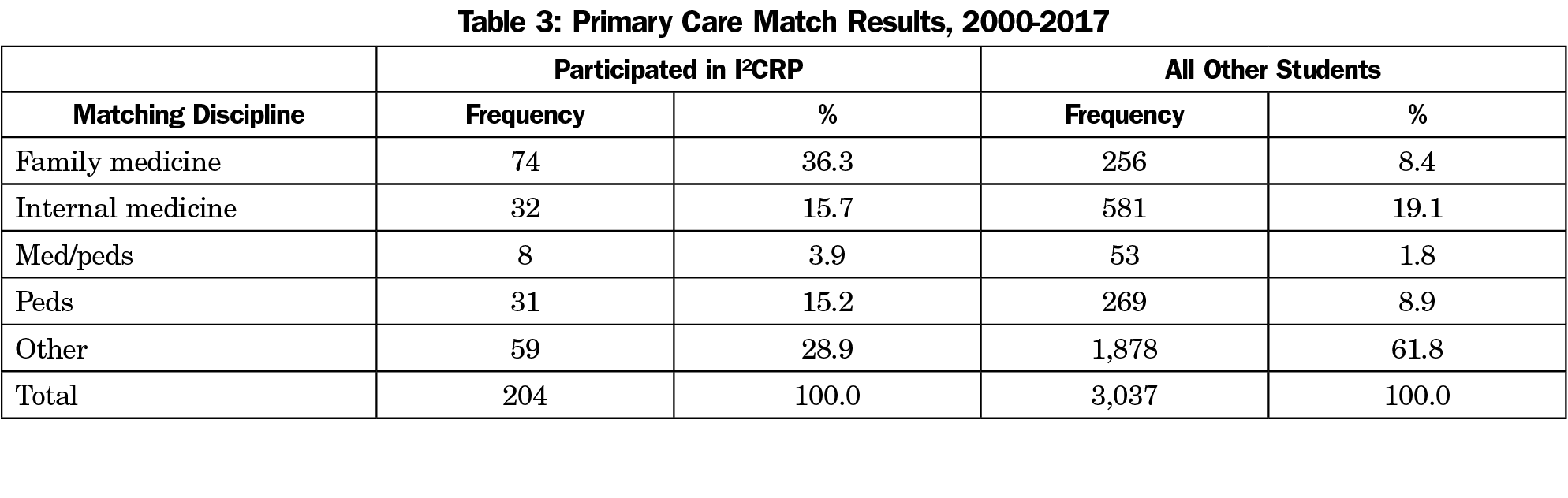

We compared the number of I2CRP graduates entering family medicine (FM), other primary care specialties (internal medicine [IM], pediatrics [peds] and medicine/pediatrics [med/peds]) and National Health Service Corps (NHSC) priority specialties (FM, IM, peds, med/peds, ob/gyn, psychiatry) to non-I2CRP VCU SOM students. We also compared I2CRP program graduates’ rates of entering general surgery, which is another specialty experiencing a workforce shortage.1 Additionally, we analyzed the proportion of I2CRP graduates who have completed training and are currently practicing in health physician shortage areas (HPSA), medically underserved areas (MUAs), or rural areas.

Data Sources and Residency Match

VCU SOM’s I2CRP program faculty maintained a database of graduates and their matched residencies since the class of 2000. Match data from VCU SOM Office of Student Affairs were used to compare the frequency of graduates entering different specialties to I2CRP graduates from 2000 to 2017.

After Residency Practice Setting

Multiple resources were used to determine the specialty, subspecialty and location of each I2CRP graduate, who were confirmed to have completed their residency or fellowship as of December 2016. Professional resources such as Doximity, LinkedIn, residency websites, and interpersonal resources such as social media or personal networks were used to verify specialties and locations. Each I2CRP graduate’s license status and current practice site were confirmed through state licensing and employer websites.

Definitions of Primary Care and Underserved

Primary care was defined as FM, IM, peds, and med/peds. NHSC priority specialties were defined as FM, IM, peds, med/peds, ob/gyn, and psychiatry. Graduates were considered to be practicing in underserved areas such as HPSA or MUA if their practice addresses were in HPSA or MUA/MUP (medically underserved populations), as designated by HRSA Data Warehouse (https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/shortage-area/by-address). Rural sites were identified using HRSA Rural Health Information Hub (https://www.ruralhealthinfo.org/am-i-rural), and defined as rural if they met criteria under the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services Rural Health Clinic status. For this study, the definition of workforce shortage includes areas designated as HPSA, MUA, and rural.

Statistical Analysis

Residency match results among I2CRP participants and non-I2CRP participants were summarized with frequencies and percentages. C2 tests were used to compare the distributions of matches over five general residency specialties (FM, IM, med/peds, peds, other) between I2CRP participants and all other medical students (SAS version 9.4, Cary, NC). These tests were repeated for primary care, NHSC priority specialties, and NHSC priority specialties plus general surgery. No comparison group was used for practice setting analysis.

This study was approved by the VCU Institutional Review Board, HM20013117.

Between 2000 and 2017, 204 graduates completed the I2CRP program. Eighty-two I2CRP graduates matched into residencies from 2000-2011, and 122 graduates matched from 2012-2017. From 2000-2017, 3,037 non-I2CRP graduates matched into residencies. Match data of these 3,241 graduates were compared between I2CRP graduates and non-I2CRP graduates. To analyze the rate of practicing physicians in HPSA, MUA, and rural areas, practice locations of 96 I2CRP practicing physicians posttraining were found. In the analysis of I2CRP practicing physicians, 90 residents, nine fellows, and nine I2CRP graduates who were inactive, had incomplete training or were unable to be located were excluded from the current practice analysis. Fellowship training included subspecialties such as gynecology-oncology (1), adult hematology-oncology (1), cardiology (1), child psychiatry (2), pediatric hematology-oncology (1), pediatric endocrinology (1), pediatric infectious disease (1), and advanced policy/education (1).

Since the start of the program, 36.3% of I2CRP graduates matched to FM, compared to 8.4% of the non-I2CRP graduates; 71.1% of I2CRP graduates matched to primary care, 80.9% to NHSC priority specialties, and 85.3% to NHSC priority plus general surgery. Participation of I2CRP had higher probability of graduates matching in FM, primary care, NHSC priority specialties, and NHSC priority plus general surgery compared to non-I2CRP graduates (P<.0001; Table 2). Of primary care match results, FM was the highest at 36.3% for I2CRP graduates, compared to IM for non-I2CRP graduates (19.1%; Table 3). Excluding those in residency and fellowship, 17 of 96 I2CRP graduates work in rural areas (18%), and 39 work in HPSA and/or MUA (41%). Three graduates are in rural but not HPSA and/or MUA. In total, 42 of 96 posttraining I2CRP (44%) graduates continue to practice in workforce shortage areas

VCU I2CRP graduates are far more likely to enter family medicine, primary care, and other workforce priority specialties as compared to non-I2CRP graduates. Of note, 41% of posttraining graduates are working in underserved areas. Including areas designated only as rural, 44% of I2CRP graduates are in workforce shortage areas. This suggests that the impact of I2CRP program completion is long lasting for a significant percentage of program graduates.

I2CRP stands out due to its 4-year longitudinal structure, cohort size of nearly 100 students, and shared focus on urban, rural, and international underserved communities. I2CRP encourages students to seek out experiences in all three settings to foster a multidimensional perspective on resources and barriers to health in diverse communities. These experiences allow students to develop an overlapping set of clinical and nonclinical skills that can then be informed by the unique needs of specific communities. The program aims to foster students’ abilities to assess needs and resources in any new setting and to adjust their approach to specific patients and communities accordingly.

Another strength of the program is the SDT framework, which inculcates relatedness, autonomy, and competence throughout 4 years of participation, and nurtures students’ interests in working with medically underserved communities. Other programs seeking to train students for careers in underserved settings may find SDT to be a useful approach to addressing their curricular and programmatic needs. Future research should include a more detailed assessment of the impact of SDT on curriculum design.

The program’s population of students with a preexisting interest and experience working with underserved communities represents inherent selection bias. This is not, however, a limitation of the program’s outcomes. Given the hostility toward primary care that students frequently experience during clinical rotations and reports of specialty disrespect, supporting students’ interest in primary care careers may be a key role of programs such as I2CRP.22,23 Similarly, focusing on students who have a declared commitment to caring for underserved communities and who perceive medical careers as a calling may sustain their interest in primary care careers.24 By identifying students with this sense of calling and by avoiding the decay in student empathy and interest in primary care that often occurs during clinical rotations, I2CRP and similar programs may maximize their impact on students’ career decisions.

Finally, this research stands out due to the total number of program graduates who enter in workforce priority disciplines, and their long-term impact in underserved settings. While burnout rates among primary care physicians remain high especially in underserved areas, a significant percentage of I2CRP graduates continue to practice in shortage areas. Given the resources needed to sustain programs such as I2CRP, tracking career outcomes must extend beyond specialty choice and residency training locations. Future research should consider the impact of duration of practice on I2CRP graduates’ career decisions, and specific factors graduates identify as having particular value in sustaining careers in underserved areas. Future assessment of I2CRP graduate outcomes may focus on SDT and how meeting needs for autonomy, competence, and relatedness may influence why some practitioners sustain these career trajectories while others might not.

It is unclear if the high number of I2CRP graduates who pursue primary care in underserved settings is attributable to students’ development of a new interest, or if the program serves to sustain students’ preexisting interest. The fact that the admission criteria for I2CRP includes assessment of students’ interest in working with medically underserved communities suggests the latter. If this is the case, it is an important aspect of the program’s success. Given the impact of the hidden curriculum and the tendency for medical students’ empathy to decrease during their clinical training, programs that sustain commitments to primary care and careers in underserved medicine may play a key role in addressing workforce needs. Rather than creating interest where none existed, programs such as I2CRP that nurture and sustain such interest may be a preferred approach.

Our results should be interpreted with the consideration of the following limitations. A small number of records remained unconfirmed due to an inability to verify graduates’ current locations based on public data. Additionally, the current practice locations of known participants may be incorrect in publicly available data. Many steps were taken to verify the graduates’ current location, including the use of personal networks when available. The website used to assess practice addresses’ HPSA/MUA status used geographical designations, and did not search for facility-specific HPSAs. This might underestimate of the number of graduates working in designated workforce shortage areas. As already noted, nine I2CRP graduates either did not complete training, are not in practice, or could not be found. If some of the program alumni who were not found were actively practicing, this number would have a small impact on our results. An additional limitation is that there is no comparison of non-I2CRP graduates working in workforce shortage areas. We were unable to find national comparison data of all medical school graduates or all physicians in workforce shortage areas.

Despite these limitations, this study shows that students with a strong commitment to work with underserved communities are influenced by early medical education to later pursue primary care specialties. The study also shows the potential of these programs to impact decisions to practice in health shortage areas.

Programs such as I2CRP have demonstrated efficacy in addressing key workforce needs, both in terms of geographic practice location and specialty. Further development and expansion of such programs is an important consideration in medical school curriculum and in meeting the social mission of medical education.25

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Dr Michelle Whitehurst-Cook, Dr Anton Kuzel, Dr Steven Crossman, and members of the Department of Family Medicine and Population Health at VCU School of Medicine for contributions to the program, as well as members of the VCU School of Medicine and the greater Richmond community who provide ongoing support for the mission of the program.

Portions of this study were presented as a poster at the STFM Medical Student Education Conference, Anaheim, CA, February 10, 2017; and as a presentation at Medical Student Education Symposium in Richmond, VA, April 26, 2017. Portions of this paper were accepted for lecture presentation for STFM Annual Spring Conference in Toronto, Ontario, Canada, April 27, 2019.

Financial Support: The I2CRP program was supported by HRSA grants D15PE80054 and D56HP10302.

Conflict Disclosure: Dr Santen receives funding from the American Medical Association for consulting on the Accelerating Change in Medical Education grant.

References

- Dall T, West T, Chakrabarti R, Reynolds R, Iacobucci W. The complexities of physician supply and demand: Projections from 2016 to 2030. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2018.

- Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL Jr, Rabin DL, Meyers DS, Bazemore AW. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs: 2010-2025. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(6):503-509. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1431

- Chung C, Maisonneuve H, Pfarrwaller E, et al. Impact of the primary care curriculum and its teaching formats on medical students’ perception of primary care: a cross-sectional study. BMC Fam Pract. 2016;17(1):135. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-016-0532-x

- Nicholson S, Hastings AM, McKinley RK. Influences on students’ career decisions concerning general practice: a focus group study. Br J Gen Pract. 2016;66(651):e768-e775. https://doi.org/10.3399/bjgp16X687049

- Boscardin CK, Grbic D, Grumbach K, O’Sullivan P. Educational and individual factors associated with positive change in and reaffirmation of medical students’ intention to practice in underserved areas. Acad Med. 2014;89(11):1490-1496. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000474

- Eidson-Ton WS, Rainwater J, Hilty D, et al. Training medical students for rural, underserved areas: A rural medical education program in California. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(4):1674-1688. https://doi.org/10.1353/hpu.2016.0155

- Goodfellow A, Ulloa JG, Dowling PT, et al. Predictors of primary care physician practice location in underserved urban or rural areas in the United States. Acad Med. 2016;91(9):1313-1321. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001203

- Ko M, Heslin KC, Edelstein RA, Grumbach K. The role of medical education in reducing health care disparities: the first ten years of the UCLA/Drew Medical Education Program. J Gen Intern Med. 2007;22(5):625-631. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-007-0154-z

- Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Santana AJ. Increasing the supply of rural family physicians: recent outcomes from Jefferson Medical College’s Physician Shortage Area Program (PSAP). Acad Med. 2011;86(2):264-269. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820469d6

- Ko M, Edelstein RA, Heslin KC, et al. Impact of the University of California, Los Angeles/Charles R. Drew University Medical Education Program on medical students’ intentions to practice in underserved areas. Acad Med. 2005;80(9):803-808. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200509000-00004

- Wendling AL, Phillips J, Short W, Fahey C, Mavis B. Thirty years training rural physicians. Acad Med. 2016;91(1):113-119. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000885

- Roy V, Hurley K, Plumb E, Castellan C, McManus P. Urban underserved program: an analysis of factors affecting practice outcomes. Fam Med. 2015;47(5):373-377.

- Girotti JA, Loy GL, Michel JL, Henderson VA. The urban medicine program. Acad Med. 2015;90(12):1658-1666. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000970

- Greer T, Kost A, Evans DV, et al. The WWAMI Targeted Rural Underserved Track (TRUST) program: an innovative response to rural physician workforce shortages. Acad Med. 2016;91(1):65-69. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000807

- Bruno DM, Imperato PJ, Szarek M. The correlation between global health experiences in low-income countries on choice of primary care residencies for graduates of an urban US medical school. J Urban Health. 2014;91(2):394-402. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11524-013-9829-4

- Ryan RM, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol. 2000;55(1):68-78. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.55.1.68

- Deci EL, Ryan RM. Facilitating optimal motivation and psychological well-being across life’s domains. Can Psychol. 2008;49(1):14-23. https://doi.org/10.1037/0708-5591.49.1.14

- Niemiec CP, Ryan RM. Autonomy, competence, and relatedness in the classroom. Theory Res Educ. 2009;7(2):133-144. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878509104318

- Kjeldmand D, Holmström I. Balint groups as a means to increase job satisfaction and prevent burnout among general practitioners. Ann Fam Med. 2008;6(2):138-145. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.813

- Glassick CE. Boyer’s expanded definitions of scholarship, the standards for assessing scholarship, and the elusiveness of the scholarship of teaching. Acad Med. 2000;75(9):877-880. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200009000-00007

- Glassick CE, Huber MT, Maeroff GIBE. Scholarship assessed. San Francisco, CA: Jossey Bass Inc; 1997.

- Brooks JV. Hostility during training: historical roots of primary care disparagement. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(5):446-452. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1971

- Alston M, Cawse-Lucas J, Hughes LS, Wheeler T, Kost A. The persistence of specialty disrespect: student perspectives. PRiMER. 2019;3:1. https://doi.org/10.22454/PRiMER.2019.983128

- Kao AC, Jager AJ. Medical students’ views of medicine as a calling and selection of a primary care-related residency. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(1):59-61. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2149

- Mullan F, Chen C, Petterson S, Kolsky G, Spagnola M. The social mission of medical education: ranking the schools. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(12):804-811. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-152-12-201006150-00009

There are no comments for this article.