Background and Objectives: Faced with a limited supply of applicants for faculty positions, increasing demands for residency faculty, and a growing number of programs, our program has increasingly filled ranks with recent residency graduates with broad scope but limited experience and training in academics. These early-career clinicians often require further mentorship as they seek advancement in clinical skills and development of teaching and scholarly activity skill sets.

Methods: To educate our recent residency graduates in teaching/scholarly activity skills, and to provide a career trajectory, we created a process to guide their maturation with milestones using the six core competencies from the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. The milestones consist of four levels of clinician/academician maturation. Each competence has goals and activities for each level of development. We validated the milestones using our physician faculty assessing time spent in academic medicine and academic rank.

Results: Faculty of higher academic rank scored higher in all competencies than faculty of lower academic rank. Correlation between systems-based practice and years in academics demonstrated statistical significance, and all other categories showed nonsignificant associations.

Conclusions: The milestones are consistent with faculty academic development and career progression, and may serve as a guide for career advancement and as a guideline for professional progression for residency clinicians. Further testing for validation in other family medicine programs is necessary, but preliminary findings indicate this milestone project may be of service to our profession.

With the increasing number of new medical schools, new family medicine residency programs, and current faculty retirements, there is a need for new physicians possessing broad-based clinical skill sets.1 A clearly defined career path in academic medicine to guide new physicians’ development is often lacking.

This raises the question of how to develop teaching/scholarly activity skill sets in faculty members. We chose to model professional growth in academic medicine after the educational milestones created to measure and report the growth of residents as part of the Next GME Accreditation System authored by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME). The milestones the residents reached provided meaningful data on the performance graduates achieved before entering unsupervised practice.2

Academic medicine utilizes milestones for several functions. Shah and colleagues developed a series of educational milestones for surgery residents to evaluate their faculty. The residents reported the milestones were easier, more effective, and objective in evaluating them.3 Garand and colleagues utilized milestones to guide nurses through the promotion and tenure process. The tool prioritized the critical milestones necessary for promotion by offering a time frame to accomplish them.4 Srinivasan and colleagues identified six core competencies and four specialized competencies for educators. They adapted skills for medical educators from the physician competencies authored by the ACGME and the roles from the Royal College’s Canadian Medical Education Directives. This tool helps educators think about the skill sets and resources needed for success in their chosen field.5 Görlitz and colleagues created six educational competencies with 57 learning objectives. The model maps faculty development initiatives at different sites within their system. The core competencies for medical educators outlines a profile of requirements for teachers.6

Our study sought to assess the ability of our faculty milestone form to guide a faculty member’s development. To internally validate its ability to measure growth, all physician members of the department completed the form. Our institutional review board reviewed this study and granted an exception from formal review.

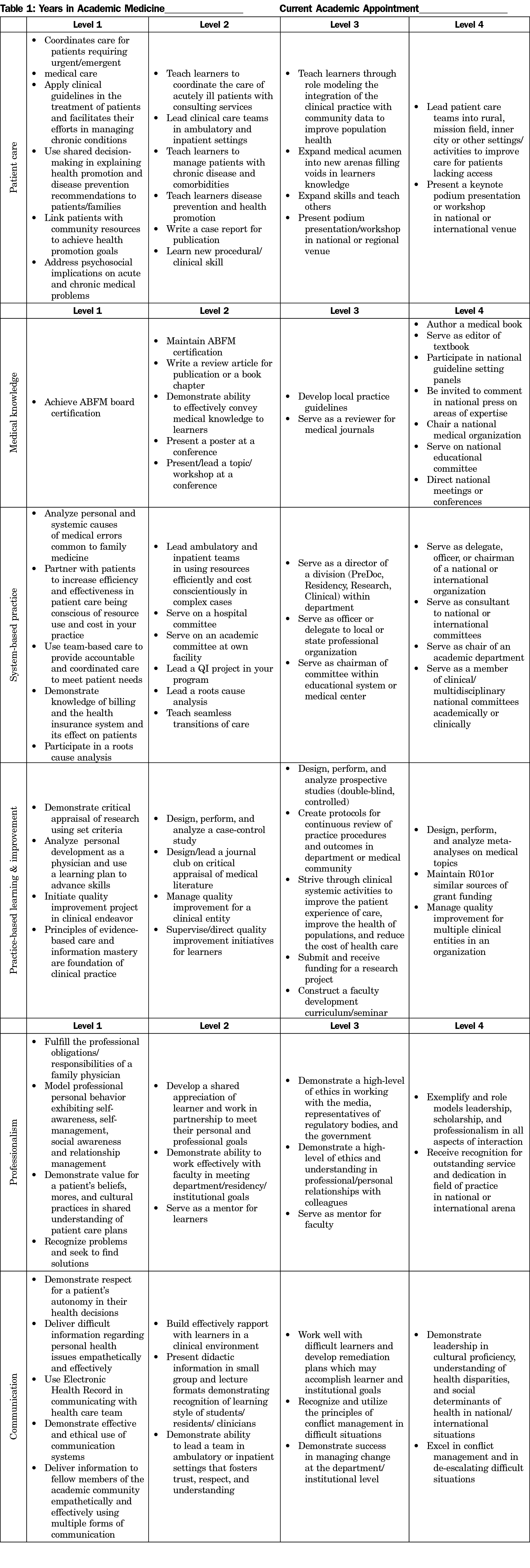

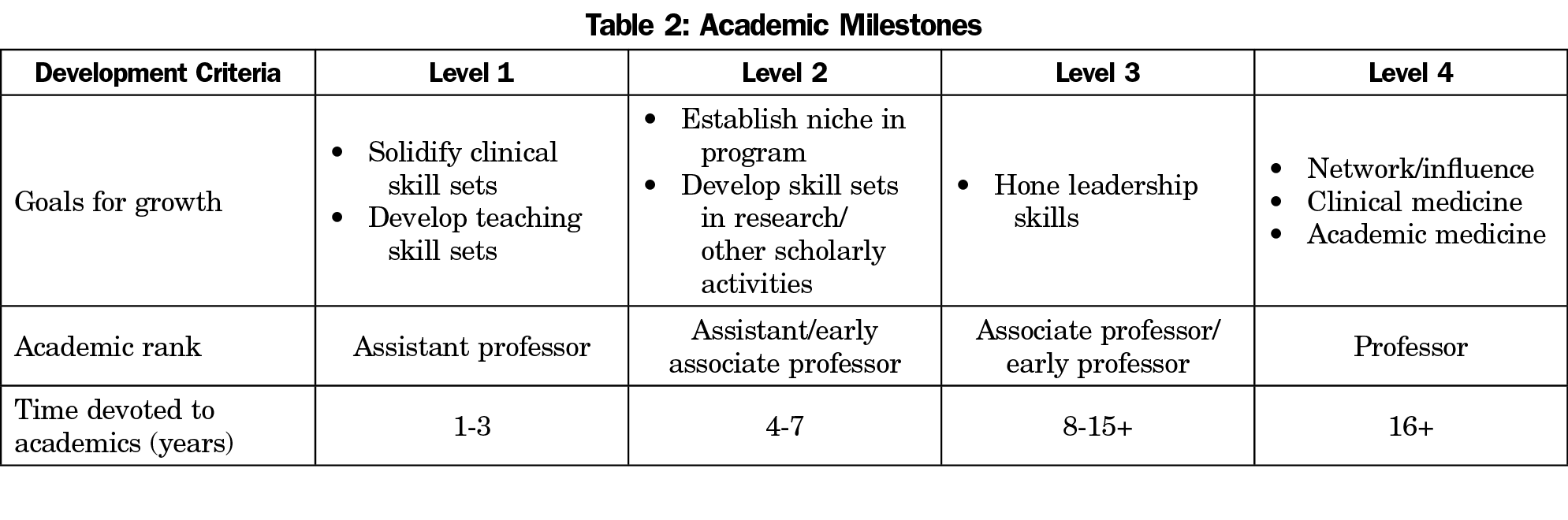

Our milestones identify four levels of progression in an academic physician’s career (Table 1). Under each of the six core competency categories are activities common in an academic physician’s job description that may meet this level of accomplishment (Table 2). The ideal first-time faculty member would possess broad generalist skill sets, perform several procedures, and provide hospital care. The level one milestones highlight this proforma, combining ACGME Milestones levels three and four. Level two faculty milestones feature teaching the level one skills and adding scholarly activity pursuits. The level three faculty milestones feature leadership positions and advanced scholarly activity. Faculty level four milestones target national recognition activities. Faculty members may score at a higher level of milestone on specific competencies as they advance in years of service in academic settings by obtaining more exposure, experience, and the availability of leadership opportunities.

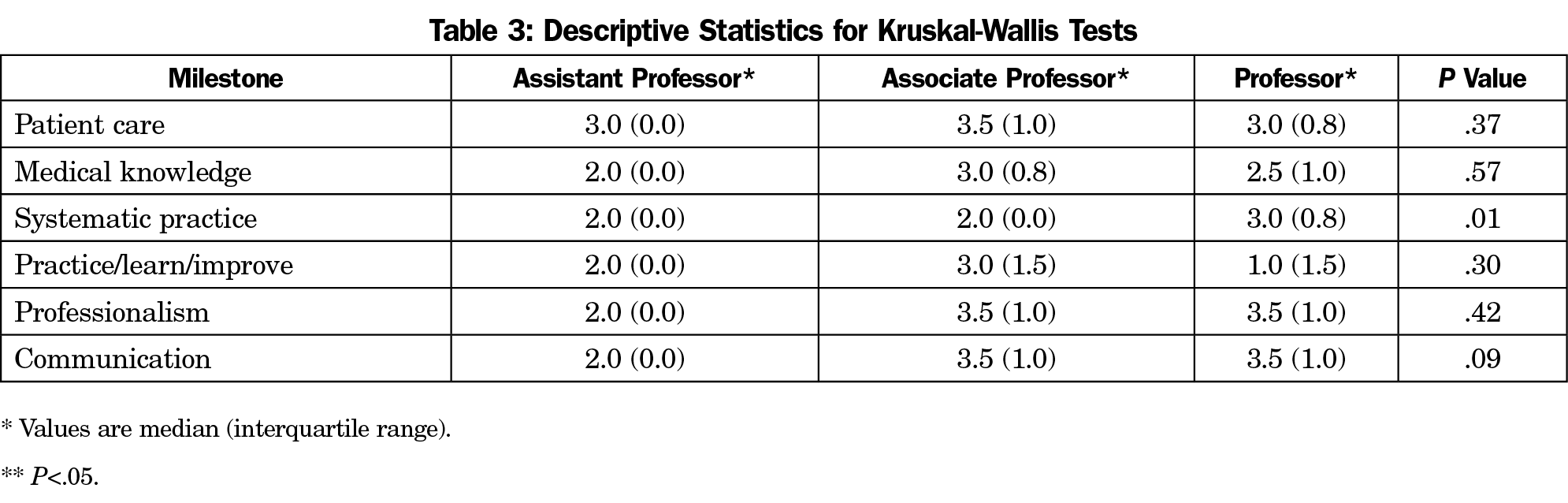

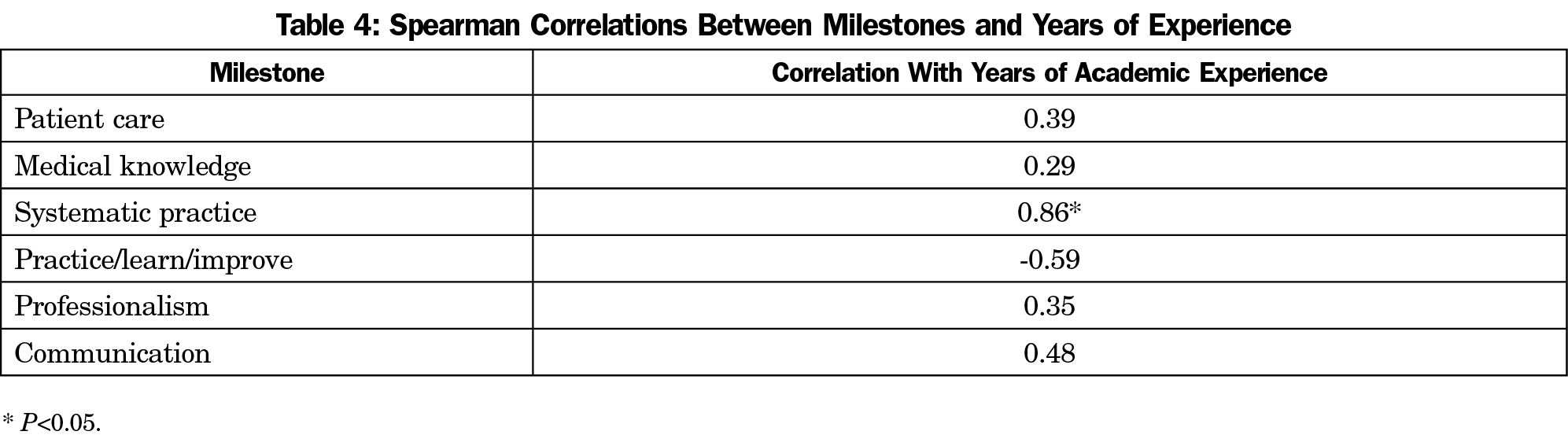

Frequency and descriptive statistics tested the sample by academic rank and years of academic experience. Skewness and kurtosis statistics checked for the statistical assumption of normality for each milestone’s distribution. If either statistic was 2.0, then Levene’s Test of Equality of Variances tested for homogeneity of variance. When statistical assumptions were violated, nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis tests evaluated for significant effects associated with academic rank across the milestones. We used post hoc pairwise Mann-Whitney U tests when a significant main effect was found. We reported medians and interquartile ranges and interpreted for the nonparametric analyses. We used Spearman’s ρ correlation to analyze the associations between years of academic experience and the six milestones.

The statistical assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance were violated for each milestone outcome, so nonparametric analyses were conducted. Nonsignificant main effects were found between the academic rank groups for all except for systemic practice, for which a significant main effect was detected. Post hoc testing found statistically significant differences between assistant professors and associate professors, assistant professors and professors, but not for associate professors and professors (Table 3). Spearman’s r correlation found a statistically significant association between systematic practice and years of academic experience, and nonsignificant associations between all other categories (Table 4).

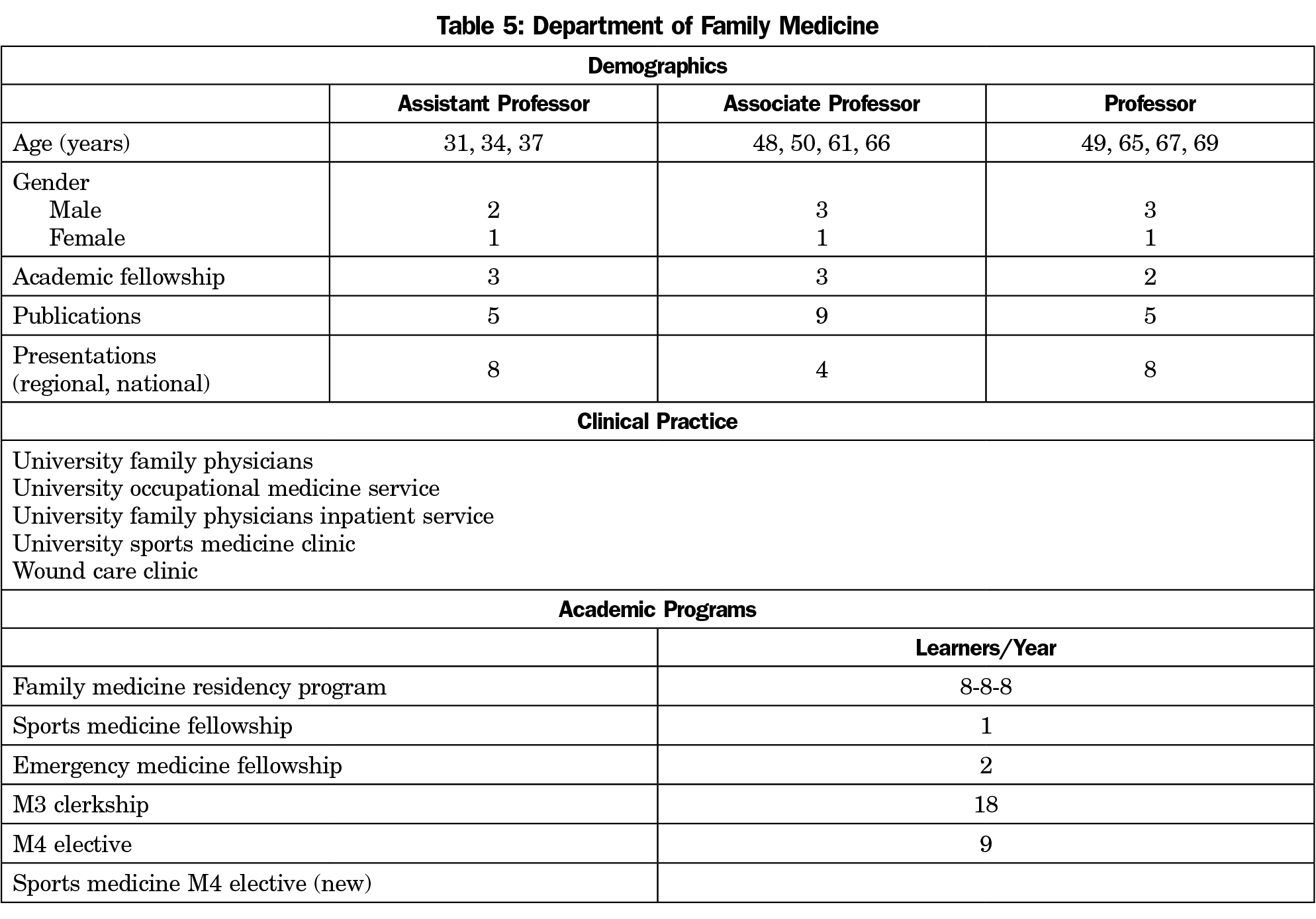

This academic milestone form effectively describes our department’s strengths and weaknesses along with anticipated development trends in the other competencies. This department’s footprint maintains high inpatient and outpatient profile, which is consistent with faculty scoring higher in patient care, professionalism, and communication categories across years in academic medicine and academic rank categories. The accelerated performance of assistant and associate professors in medical knowledge and practice improvement is likely related to six of the seven faculty in these ranks having completed academic fellowships compared to 59% for full professors (Table 5).

This department’s profile is likely unique to programs with similar academic/clinical environments. A program’s profile would differ by the health care system’s emphasis on clinical, teaching or research pursuits and whether they reside on a medical school campus, or are a stand-alone community residency.

The limitations of this study limit generalizability. The total number of faculty evaluated was small. Further, all participants were located at the same site, and each author participated.

Our milestones provide a matrix whereby academic programs can guide professional development. These guidelines are not intended as a checklist for academic promotion or as a framework for evaluations. They are not intended to bring about punitive measures, but offer insight on career trajectory. Based on personal characteristics and skills, physicians gravitate toward the levels of their interest and expertise. For this reason, these guidelines should not function as a plumb line to evaluate individual success or serve to define a productive academic career.

The Milestones Form should be tested in other family medicine programs to determine generalizability, its ability to define strengths/weaknesses, and gauge faculty members’ development. If these are realized the form could guide faculty selection, enhance faculty member’s strengths while minimizing weaknesses, and nurture the development of faculty within departments.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Mack Worthington, MD for his counsel on the Milestone form and Ms Diane Jones for her preparation of the manuscript.

References

- Petterson SM, Rayburn WF, Liaw WR. When do primary care physicians retire? Implications for workforce projections. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(4):344-349. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1936

- Nasca TJ, Philibert I, Brigham T, Flynn TC. The Next GME Accreditation System— rationale and benefits. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(11):1051-1056. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMsr1200117

- Shah D, Goettler CE, Torrent DJ, et al. Milestones: The Road to Faculty Development. J Surg Educ. 2015;72(6):e226-e235. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2015.06.017

- Garand L, Matthews JT, Courtney KL, et al. Development and use of a tool to guide junior faculty in their progression toward promotion and tenure. J Prof Nurs. 2010;26(4):207-213. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.profnurs.2010.01.002

- Srinivasan M, Li ST, Meyers FJ, et al. “Teaching as a Competency”: competencies for medical educators. Acad Med. 2011;86(10):1211-1220. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c5b9a

- Görlitz A, Ebert T, Baver D, Grast M, Hofer M, Lammerding-Köppel M, Fabry G. Core Competencies for Medical Teachers (KLM). A position paper of the GMA Committee on Personal and Organizational Development in Teaching. GMS Zeitschrift für Medizinische Austiktung. 2015;32(2);1/14-7/14. https://doi.org/10.3205%2Fzma000965

There are no comments for this article.