Background and Objectives: Untreated maternal depression negatively impacts both the mother and her children’s health and development. We sought to assess family medicine program directors’ (PDs) knowledge and attitudes regarding maternal depression management as well as resident training and clinical experience with this disorder.

Methods: Data were gathered through the Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) national survey of family medicine PDs in US and Canadian programs, from January through February, 2018.

Results: Surveys were completed by 298 PDs (57.1% response rate) who were majority male (58.9%) and white (83.8%). Nearly all (90.2%) PDs agreed that family physicians should lead efforts to minimize the impact of maternal depression on child well-being. According to PD report, in the family medicine clinics where residents train, most (77.3%) have a clinic process that ensures that routine screening for depression occurs, and 54.4% do some screening of mothers during pediatric visits. Only 18.2% report routinely taking steps to minimize the impact of the mothers’ depression on child well-being. Finally, 41.3% of PDs reported being familiar with the literature on the impact of maternal depression on children; self-reported familiarity was significantly associated with more comprehensive resident training on this topic.

Conclusions: Family medicine residency program directors are supportive of training in maternal depression, though their current knowledge is variable and there are opportunities to enhance care of mothers and children impacted by this common and serious disorder.

Maternal depression is a worldwide health problem, and one in 10 US children are cared for by a depressed mother.1-3 Symptoms of depression can negatively impact parent-child interactions and other parenting practices,4,5 as well as child development, behavior, and mental health.3-9 Screening and interventions for depressed mothers are needed in primary care settings to promote the health and well-being of mother and child.10-12

Family physicians are uniquely positioned to take a two-generational approach to identify and support depressed mothers and their children since they may have mother, child, or both as patients. While most physicians believe it is their responsibility to recognize maternal depression, more than one-third report that they rarely or never assess for depression in mothers.13 While physician training and knowledge about maternal depression increases the likelihood that physicians will take steps to identify and manage maternal depression,14 little is known about resident training on this topic. Our objective was to explore family medicine (FM) resident training in screening and treatment of maternal depression during the child-rearing years, focusing on reducing the negative impact of this disorder on infant and child health and wellness, and to compare approaches based on PD self-reported familiarity with the topic.

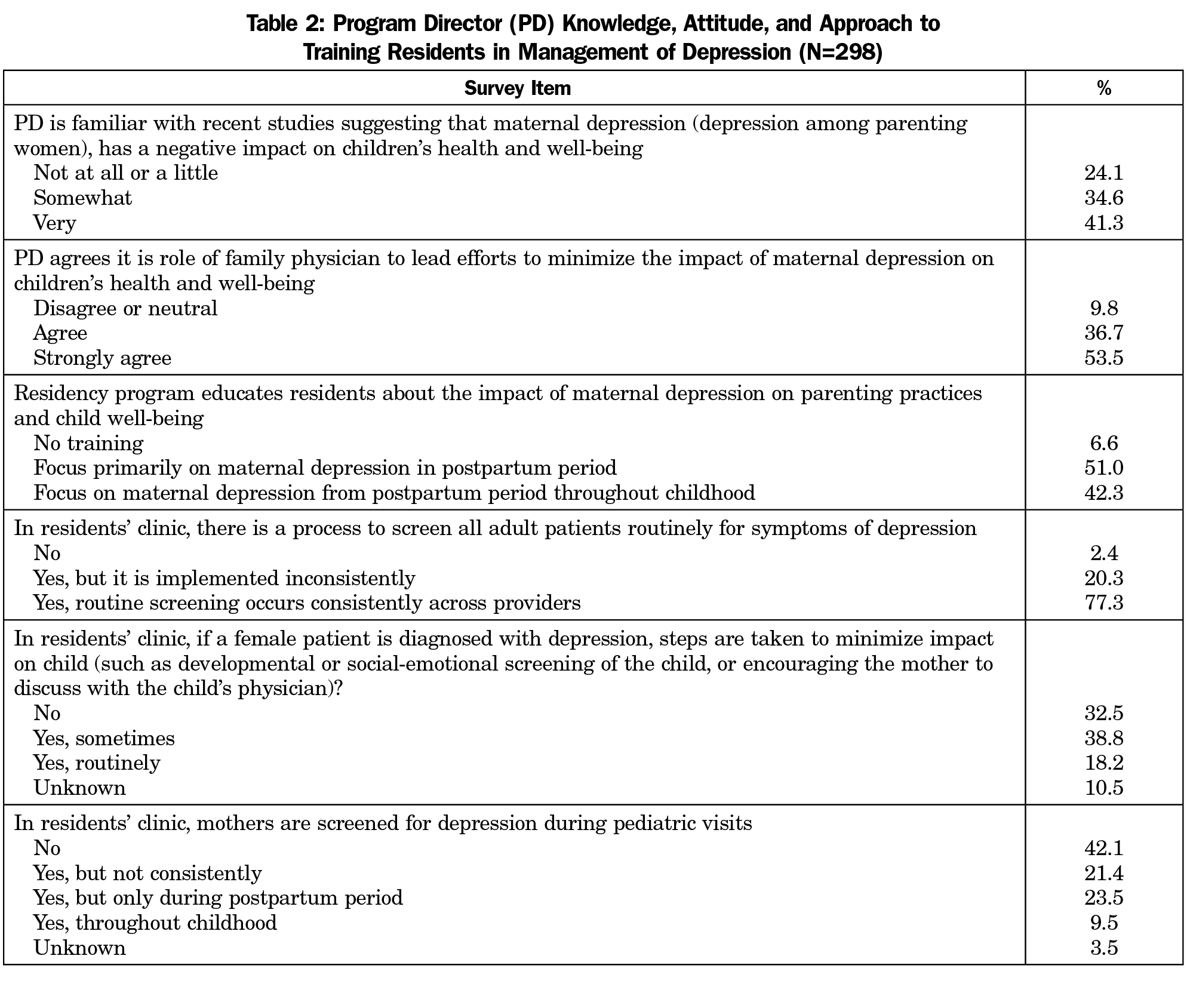

Data were gathered through the Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) online survey of family medicine program directors (PDs) of programs accredited by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. The methodology has been described previously.15 The author team designed survey questions to describe the training and clinical experience that residents in family medicine programs receive in methods of screening for and managing symptoms of maternal depression from the postpartum period throughout childhood (Table 2). Items addressed the goal of reducing negative impact of maternal depression on infant and child health and development. With SPSS Version 22 (IBM Corporation), we used descriptive statistics and χ2 tests to describe PD reports of the training and clinical experience of residents and to explore the relationship between PD self-reported knowledge of the topic and the training approach.

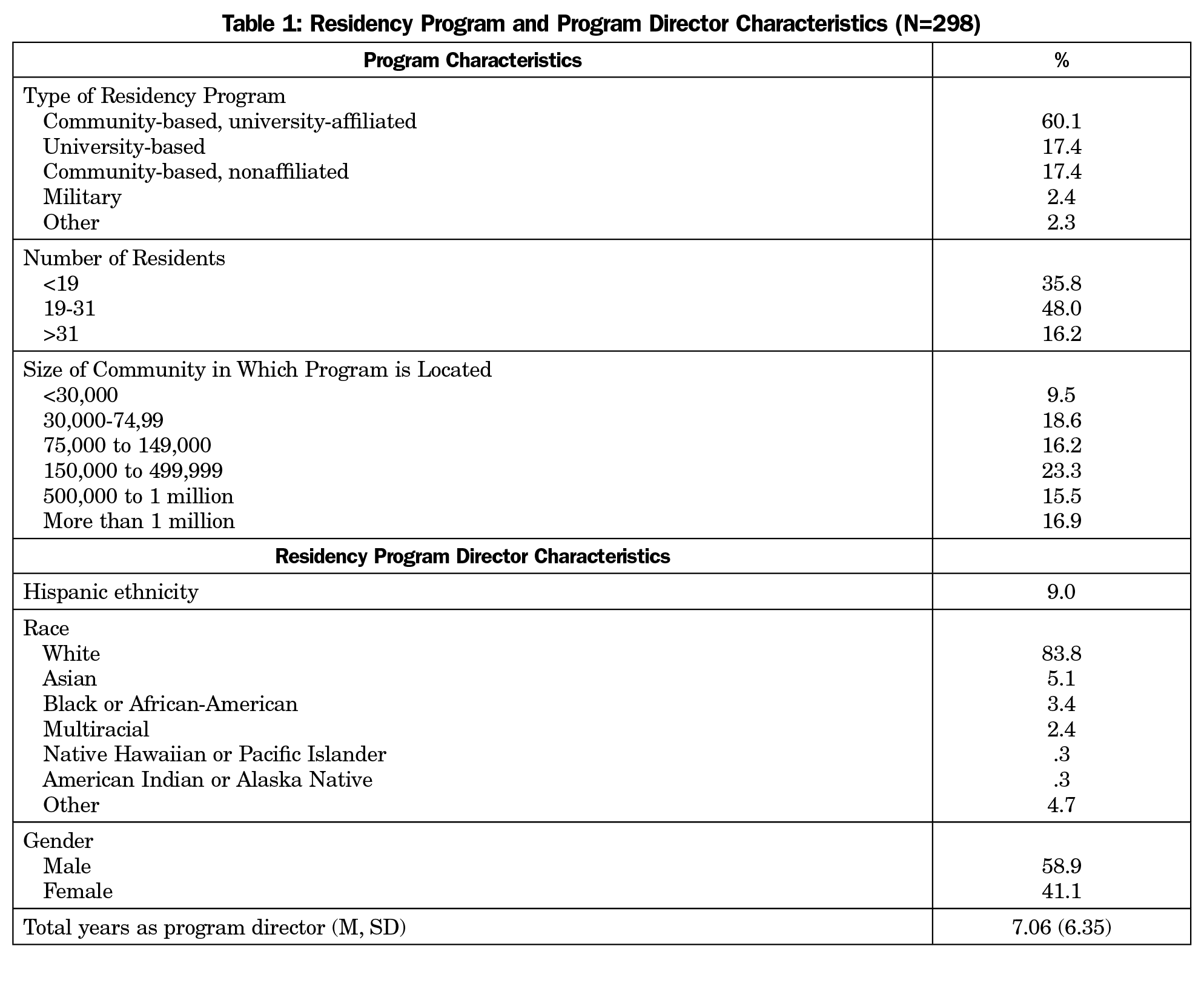

Of the 549 known PDs, 13 opted out of CERA surveys and 14 emails could not be delivered, resulting in a final sample size of 522. The survey was completed by 298 PDs for a response rate of 57.1% (298/522). As shown in Table 1, responding PDs were located in all regions of the United States. The PDs were majority male (58.9%) and white (83.8%) with an average of 7.06 (SD=6.35) years of experience as PD.

As shown in Table 2, most PDs reported that their residency programs provide education about the impact of maternal depression on parenting practices and child well-being (93.4%), though the focus in half of these programs is limited to postpartum depression (51.0%). In the family medicine clinics in which residents train, PDs reported that most (77.3%) have a clinic process that ensures that routine screening for depression occurs, 54.4% engage in some level of screening of mothers during pediatric visits, and 9.5% screen throughout childhood. When a mother is diagnosed with depression, 18.2% reported routinely taking steps to minimize the impact of the mothers’ depression on child well-being (eg, developmental or social-emotional screening of the child or encouraging the mother to discuss her diagnosis with the child’s physician).

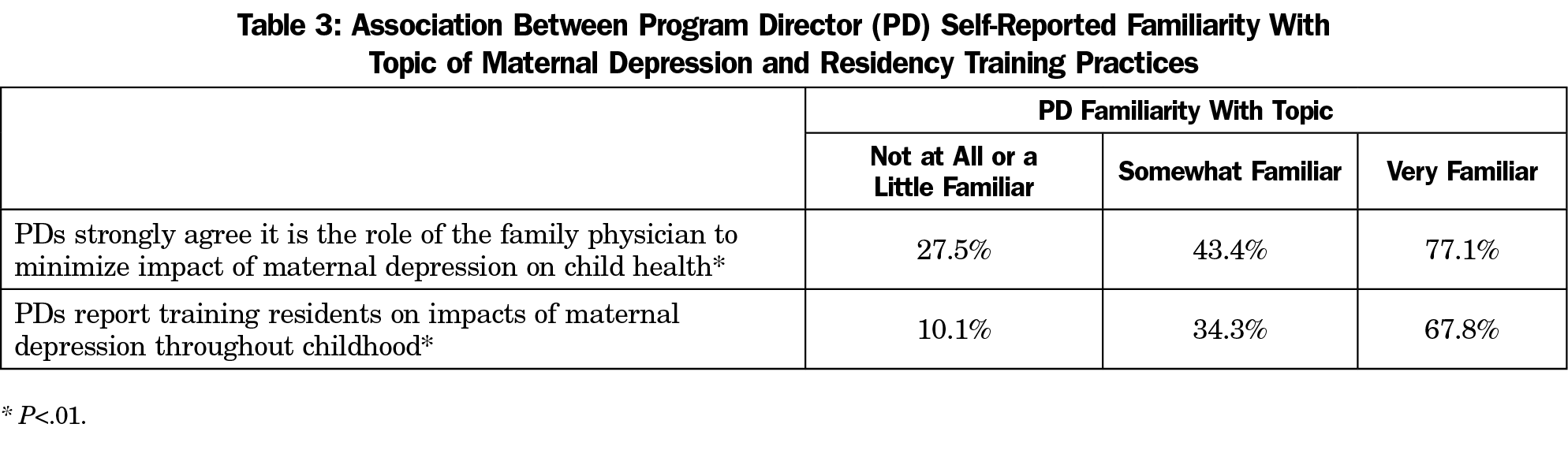

Less than half (41.3%) of PDs reported being very familiar with recent studies suggesting that maternal depression has a negative impact on children’s health and well-being. As shown in Table 3, The stronger the self-reported PD knowledge of the literature, the more likely they were to agree it is the role of the family physician to minimize impact of depression the child (χ2 [4, N=286]=59.71, P<.001), and to report residents are trained comprehensively on the problem of maternal depression (χ2 [4, N=286]=88.39, P<.001; Table 3).

We found that while most residents are trained to address maternal depression, there may be opportunities to increase awareness about the impact of maternal depression on child well-being and clinical approaches to supporting mothers and their children. As family physicians implement screening approaches consistent with the recommendations of both the American Academy of Pediatrics for screening for maternal depression at child visits during infancy and the US Preventive Services Task Force for screening for adults,10,11 they may be particularly well positioned to explore the impacts on both mother and child.

Beyond screening, many options exist for supporting mothers with depression and their children.16 For example, health professionals can provide mothers with referrals to supports such as home visiting and high-quality child care.17 They can also provide psychoeducation to reduce stigma and educate about the impact of maternal depression on parenting and child development, with an emphasis on ways mothers can support healthy development through play, consistent routines, reading, and more.18 Monitoring mood and supporting mothers through technology such as mobile apps may also be a useful approach.19 The IMPLICIT network has demonstrated that well-child visits in family medicine clinics can be used to identify and support high-risk mothers and children20 and that mothers are interested in health advice from their child’s physician even if they receive their health care from a different provider.21 Enhancing the knowledge base of PDs on these approaches may be one avenue to promote change given the association we found between the self-reported knowledge of PDs on this topic and the comprehensiveness of the approach to resident training on this topic.

A limitation is that our study relied on PD report to describe the training and clinical experiences of residents. Future studies should examine this issue from the perspective of the trainees and integrated behavioral health faculty, as PDs are unlikely to be aware of every aspect of resident experiences. Our measure of PD self-reported knowledge of this topic was also limited to one item. Additional research is needed to identify opportunities to enhance the training and clinical experiences of family medicine residents to better support high-risk mothers and their children in ways consistent with emerging science.

References

- Ertel KA, Rich-Edwards JW, Koenen KC. Maternal depression in the United States: nationally representative rates and risks. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2011;20(11):1609-1617. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2010.2657

- Howard LM, Molyneaux E, Dennis CL, Rochat T, Stein A, Milgrom J. Non-psychotic mental disorders in the perinatal period. Lancet. 2014;384(9956):1775-1788. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61276-9

- Bennett IM, Schott W, Krutikova S, Behrman JR. Maternal mental health, and child growth and development, in four low-income and middle-income countries. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2016;70(2):168-173. https://doi.org/10.1136/jech-2014-205311

- Cummings EM, Keller PS, Davies PT. Towards a family process model of maternal and paternal depressive symptoms: exploring multiple relations with child and family functioning. J Child Psychol Psychiatry. 2005;46(5):479-489. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2004.00368.x

- Netsi E, Pearson RM, Murray L, Cooper P, Craske MG, Stein A. Association of persistent and severe postnatal depression with child outcomes. JAMA Psychiatry. 2018;75(3):247-253. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.4363

- Carter AS, Garrity-Rokous FE, Chazan-Cohen R, Little C, Briggs-Gowan MJ. Maternal depression and comorbidity: predicting early parenting, attachment security, and toddler social-emotional problems and competencies. J Am Acad Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 2001;40(1):18-26. https://doi.org/10.1097/00004583-200101000-00012

- Weissman MM, Pilowsky DJ, Wickramaratne PJ, et al; STAR*D-Child Team. Remissions in maternal depression and child psychopathology: a STAR*D-child report. JAMA. 2006;295(12):1389-1398. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.295.12.1389

- Goodman SH, Rouse MH, Connell AM, Broth MR, Hall CM, Heyward D. Maternal depression and child psychopathology: a meta-analytic review. Clin Child Fam Psychol Rev. 2011;14(1):1-27. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10567-010-0080-1

- Stein A, Pearson RM, Goodman SH, et al. Effects of perinatal mental disorders on the fetus and child. Lancet. 2014;384(9956):1800-1819. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61277-0

- Siu AL, Bibbins-Domingo K, Grossman DC, et al; US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF). Screening for depression in adults: US preventive services task force recommendation statement. JAMA -. JAMA. 2016;315(4):380-387. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.18392

- Committee on Practice and Ambulatory Medicine Bright Futures Periodicity Schedule Workgroup. 2017 Recommendations for Preventive Pediatric Health Care. Pediatrics. 2017;139(4):e20170254. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2017-0254

- Chae SY, Chae MH, Tyndall A, Ramirez MR, Winter RO. Can we effectively use the two-item PHQ-2 to screen for postpartum depression? Fam Med. 2012;44(10):698-703.

- Leiferman JA, Dauber SE, Heisler K, Paulson JF; Leiferman J a. Dauber SE, Heisler K, Paulson JF. Primary care physicians’ beliefs and practices toward maternal depression. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(7):1143-1150. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2007.0543

- Leiferman JA, Dauber SE, Scott K, Heisler K, Paulson JF. Predictors of maternal depression management among primary care physicians. Depress Res Treat. 2010;2010:671279. https://doi.org/10.1155/2010/671279

- Mainous AG III, Seehusen D, Shokar N. CAFM Educational Research Alliance (CERA) 2011 Residency Director survey: background, methods, and respondent characteristics. Fam Med. 2012;44(10):691-693.

- Perry DF, Miranda J, Ammerman RT, Beardslee WR. Depression in mothers: more than the Blues—a toolkit for family service providers. 2013. https://store.samhsa.gov/shin/content/SMA14-4878/SMA14-4878.pdf. Accessed April 10, 2019.

- Earls MF; Committee on Psychosocial Aspects of Child and Family Health American Academy of Pediatrics. Incorporating recognition and management of perinatal and postpartum depression into pediatric practice. Pediatrics. 2010;126(5):1032-1039. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2010-2348

- Trussell TM, Ward WL, Conners Edge NA. The Impact of Maternal Depression on Children: A Call for Maternal Depression Screening. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 2018;57(10):1137-1147. https://doi.org/10.1177/0009922818769450

- Hantsoo L, Criniti S, Khan A, et al. A Mobile Application for Monitoring and Management of Depressed Mood in a Vulnerable Pregnant Population. Psychiatr Serv. 2018;69(1):104-107. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.201600582

- Srinivasan S, Schlar L, Rosener SE, et al. Delivering Interconception Care During Well-Child Visits: An IMPLICIT Network Study. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(2):201-210. https://doi.org/10.3122/jabfm.2018.02.170227

- Rosener SE, Barr WB, Frayne DJ, Barash JH, Gross ME, Bennett IM. Interconception care for mothers during well-child visits with family physicians: an IMPLICIT network study. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(4):350-355. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1933

There are no comments for this article.