Background and Objectives: Adequate parental leave policies promote a supportive workplace environment. This study describes how US family medicine (FM) residency program parental leave policies compare to reported leave taken by residents and faculty.

Methods: This is a descriptive study of questions from a 2017 Council of Academic Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of accredited US FM program directors.

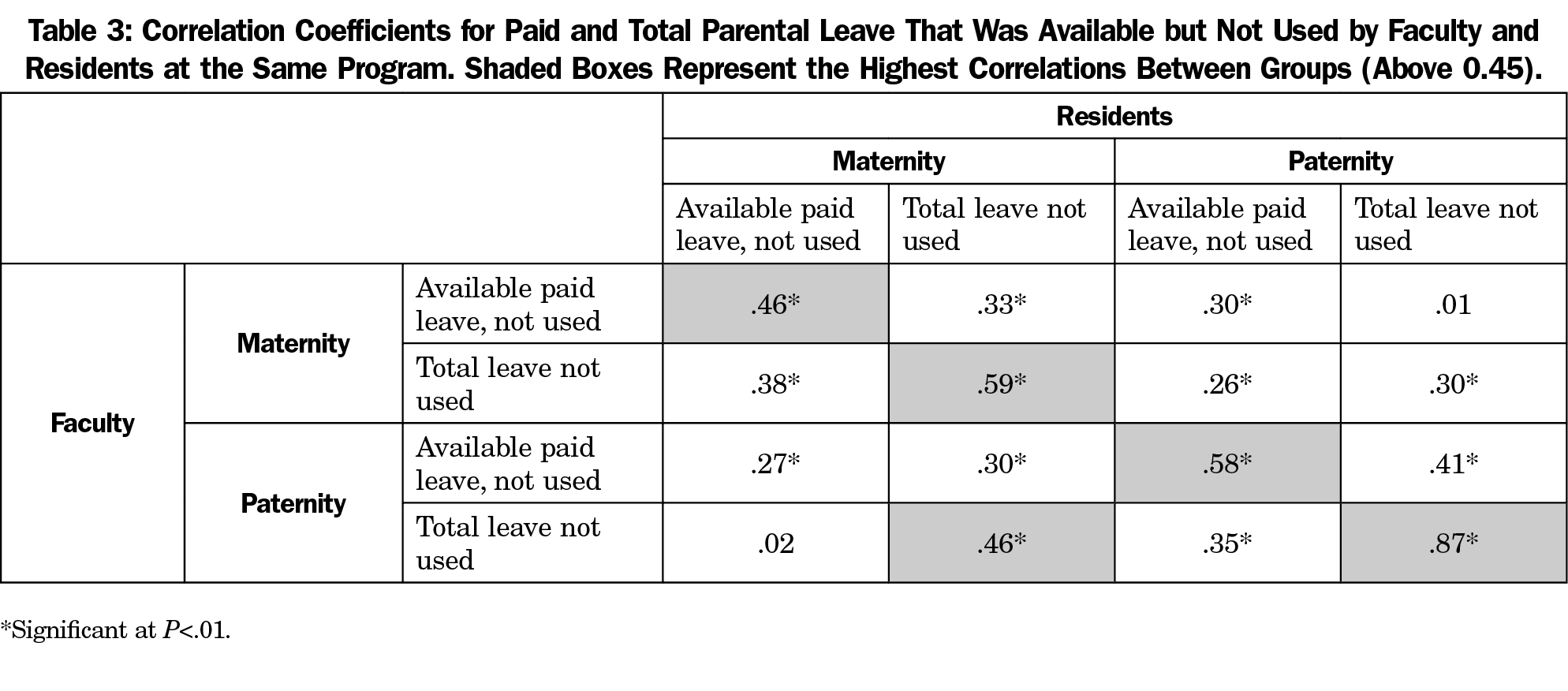

Results: The overall survey response rate was 54.6% (261/478). Paid maternity leave policies varied widely (0 to >12 weeks; mean=5.3 weeks for faculty and 4.5 weeks for residents); paid paternity leave ranged from 0 to 12 weeks (mean=2.7 weeks for faculty and 2.4 weeks for residents). Some FM programs reported offering residents (29.1%) and faculty (28.5%) no paid maternity leave; 37.2% offered residents and 40.4% offered faculty no paid paternity leave. Both female and male faculty took significantly less paid leave than was offered (maternity leave: faculty 0.6 weeks less, P<.01; residents 0.5 weeks less, P<.01; paternity leave: faculty 1.6 weeks less, P<.01; residents 0.6 weeks less, P<.01). The amount of paid and total maternity and paternity leave surrendered by residents was strongly correlated with the amount surrendered by faculty in the same program (correlation coefficients 0.46-0.87, P<.01). Residents in smaller programs, and programs with a rural focus, surrendered more parental leave.

Conclusions: Programs vary widely in their parental leave offerings, and FM residents and faculty frequently take less parental leave than offered. As the amount of leave taken by residents and faculty at the same institution is correlated, institutional culture may contribute to parental leave use.

Adequate parental leave policies are an important component of creating supportive workplace environments. Many residents are parents or become parents during training, and report higher satisfaction with their experience when they feel their newborn’s needs are met, including maximizing the opportunity to breastfeed.1,2 A 2013 resident physician survey of various disciplines at one institution reported that 41% had children, 7% were pregnant or had pregnant partners, and about 40% planned to have a first child or another child during residency.3 This contrasts with a 1983 survey that found only 13% of married women had a child during residency.4 The growing number of trainees who plan childbearing makes the topic of parental leave increasingly important for medical educators and for graduate medical education governing bodies that are responsible for developing policy and procedures that affect these professionals.

Maternity leave policies may also affect recruitment and retention of women in academic careers, as policies often affect women at a time when they are beginning their roles as faculty. Although women make up nearly half of medical school matriculants, they constitute only about one-third of academic faculty, and leave academic careers at a higher rate than men.5 Residency faculty are role models and mentors as residents make decisions about career paths and practice locations, and the environment where women train strongly influences these choices.6-9 Creating policies that allow women faculty to succeed is essential for meeting the ongoing need for teaching faculty who will develop the future physician workforce.10

Leave policies for nonchildbearing parents are also important. Although no studies have examined the affect of parental or adoptive leave on physician recruitment, studies have reported the positive impact of paternity leave on families. Fathers who take leave around the time of childbirth, especially 2 weeks or more, are more likely to be involved in subsequent childcare activities, which correlates with higher satisfaction with parenting and improved developmental outcomes for children.11-14

Despite this, leave policies vary greatly across programs and disciplines.8,15-18 A 2016 survey of surgery residency programs showed less than half of programs had a paternity leave policy and, when present, paternity leave was typically 1 week.2 Pediatric program directors reported 61% had policies for paternity leave and approximately one-third had policies for domestic partnerships or same-gender unions.16 Obstetrics residency program directors reported 55% had policies in place for nonchildbearing parents.19 Maternity leave policies are reported more frequently,2,8,16,19 but length of leave varies by program and often includes vacation, sick leave, or disability.15,18 Importantly, many of these surveys describe policies rather than actual leave practices.

The impact of parental leave on residency progress varies. A 6-week leave may not delay graduation at all, or may delay board certification by up to 1 year, depending on specialty.20 One pediatric survey noted that the mean amount of leave residents could take without making up time was 3 weeks, regardless of the reason for the absence.16 A 2011 survey found that family medicine (FM) residents take an average of 6.5 weeks of maternity leave, but did not explore whether leave was paid, whether time was expected to be made up, or the differences between organizational policy and amount of leave taken.1 In a more recent survey, over 40% of family medicine program directors noted that a high proportion (81%-100%) of female residents who take parental leave at their program will extend residency.21 To mitigate the need for program extensions, some offer at-home or reading electives to new resident parents as a way to allow a small amount of residency work to be completed at home, a practice identified in the literature as supportive for new parents.22,23

The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP) parental leave recommendations suggest that programs encourage residents to take the longest leave possible, prioritize time for mother-child bonding, offer electives that can be completed at home, and provide clear policies about patient care during a resident’s absence.24 Nonetheless, there are no strict overarching policies governing the duration of resident maternity or paternity leave.

Similarly, although parental leave policies for academic faculty members have been discussed in the literature,25,26 we are aware of no studies exploring the experiences of FM faculty. This is important, because gender-specific policies and the degree of institutional support for parents can vary significantly across specialty departments.5 Furthermore, even the most generous policies, if not supported by institutional culture, may not be meaningful.

Programs must balance the needs of residents and faculty on leave with the workload of those who remain. Leave in educational programs, as in all practices, must be balanced against patient care needs. Because of these conflicting demands, parental leave practices may be less generous in smaller programs, or possibly rural programs, where there may be less available cross-coverage.

The purpose of our study was to describe parental leave policies of US FM residency programs, to identify factors that predict parental leave, and to compare policies to leave actually taken by residents and faculty members. Although not all FM faculty are employed by residency programs, this survey of program directors is a first step in understanding the family leave policies and practices of a large group of academic family physicians in the United States.

We surveyed all program directors of US FM residency programs accredited by the American Council of Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), as part of a Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey. These biannual omnibus surveys include standard demographic questions describing the residency programs and program directors as well as questions submitted by various researchers on different topics.27 Pretesting was done using FM educators who were not program directors, and questions were modified for flow, readability, and consistency.

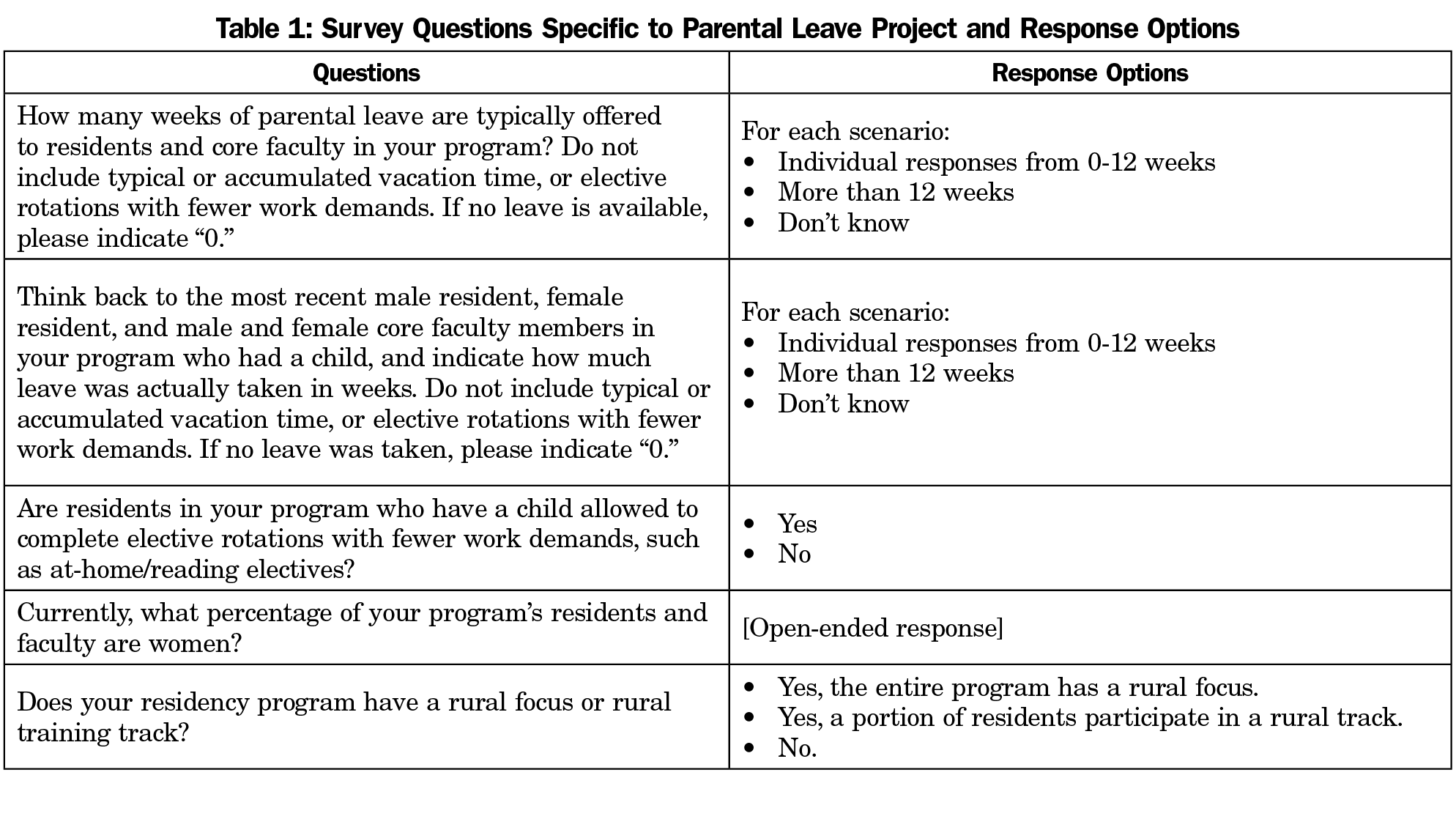

Our questions focused on the amount of parental leave offered and taken by residents and faculty, excluding vacation time or elective rotations with fewer work demands (Table 1). Program directors were asked to describe leave taken by the last residents and core faculty members who took maternity or paternity leave, using the ACGME definition of “core.”28 They were also asked whether their program had a rural focus, rural training track, or neither; the percentage of female residents and faculty members; and whether elective rotations with fewer work demands were offered to new parents.

Data were collected from January to March of 2017. The CERA program sent email invitations to residency program directors with a link to the online survey. Five follow-up emails were sent to remind nonparticipants about the survey. At the time of the survey there were 499 US FM residency programs. Ten program directors had previously opted out of surveys and 11 emails could not be delivered, for a final population size of 478.

We analyzed data using IBM SPSS Statistics, version 24 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY). Response options for weeks of leave were ordinal numbers 0 through 12 and “>12”; for analyses we converted all >12 week responses to 13 weeks. We calculated frequencies and descriptive statistics on weeks of maternity and paternity leave for residents and faculty, Pearson correlations to compare weeks of maternity and paternity leave between residents and faculty, and student t-tests and one-way analysis of variance (converting to Welch test if homogeneity of variance existed) to compare results based on program size and rural focus. The overall CERA survey asked the number of residents in each program with response options of <19, 19-31, and >31; we initially ran comparisons with all three program sizes, but after not finding significant differences between the 19-31 and >31 size programs we grouped to small (<19 residents) and large (19 or more residents) for the remainder of the analyses. We defined programs as rurally-focused if either the entire program had a rural focus or a portion of residents participated in a rural track. We built multiple regression models for total and paid maternity and paternity leave for residents and faculty, controlling for rural program focus (yes/no), percentage of women faculty, percentage of women residents, program size (small/large), and program director gender. Significance was set at P<.05.

The AAFP Institutional Review Board approved the study.

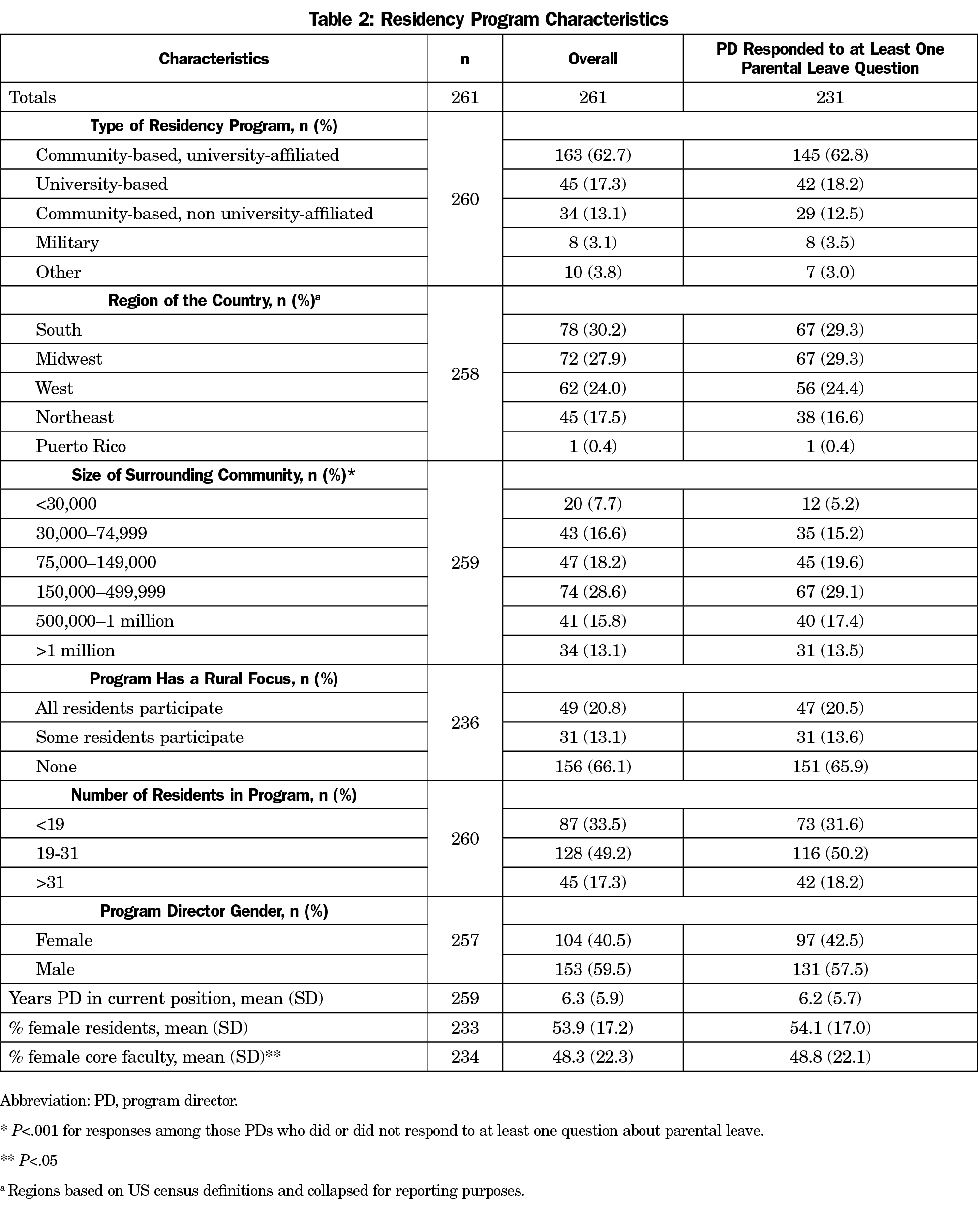

The overall survey response rate was 261/478 (54.6%). Residency program characteristics are summarized in Table 2. About two-thirds of respondents were from community-based, university-affiliated programs, and over half were from either the South or Midwest. Almost 25% were in communities of less than 75,000 people, one-third had a rural focus, and two-thirds had 19 or more residents. Most of the program directors answered at least one question about parental leave benefits. Nonrespondents’ programs tended to be in smaller communities (P<.001) and had lower percentages of female core faculty members than respondents’ programs (mean 30% [SD=20.2] vs 48.8% [SD=22.1], respectively; P<.05). There were no other significant differences between the programs of responding and nonresponding directors.

A wide range of paid maternity and paternity leave policies were reported, from 0 to >12 weeks (Figure 1). Notably, almost 30% of responding programs offered no paid maternity leave and almost 40% offered no paid paternity leave, to residents or faculty. Only two programs offered more than 12 weeks of paid maternity leave to either residents or faculty.

On average, program policies offered faculty slightly more paid parental leave than residents (maternity average 5.3 weeks for faculty vs 4.5 weeks for residents, P<.01; and paternity average 2.7 weeks for faculty vs 2.4 weeks for residents, P<.01).

Unpaid leave policies were more generous, allowing residents to have an average of 11.5 weeks total (combined paid and unpaid) maternity leave and 9.0 weeks paternity leave. Faculty were offered an average of 12.8 weeks maternity and 10.0 weeks paternity leave. Four programs offered no resident maternity leave and four offered no faculty maternity leave. Ten programs (5.5%) offered no paternity leave to residents and twelve (7.3%) offered none for faculty.

For both residents and faculty, the amount of paid maternity and paternity leave used was significantly less than the amount of paid leave offered (P<.01). Residents, on average, did not take 0.5 weeks of paid maternity leave offered (SD=2.4); faculty did not take an average of 0.6 weeks (SD=2.9). Similarly, residents did not take an average of 0.6 weeks of paid paternity leave offered (SD=2.8) and faculty did not take an average of 1.6 weeks (SD=2.7).

Parental leave offered and accepted for each program were correlated in several important ways. The amount of paid maternity and paternity leave each program offered faculty was strongly correlated (r=0.64; percentage of variance 41%; P<.01), as was the amount of paid maternity and paternity leave offered residents (r=0.62; POV 38.4%, P<.01). The amount of paid maternity and paternity leave offered residents was strongly correlated with the amount of paid leave offered faculty at the same program (maternity: r=.77; POV 59.3%; P<.01; paternity: r=.82; POV 67.2%; P<.01). The amount of paid and total maternity and paternity leave that was available but not used by residents was also strongly correlated with the amount available but not used by faculty in the same program (Table 3).

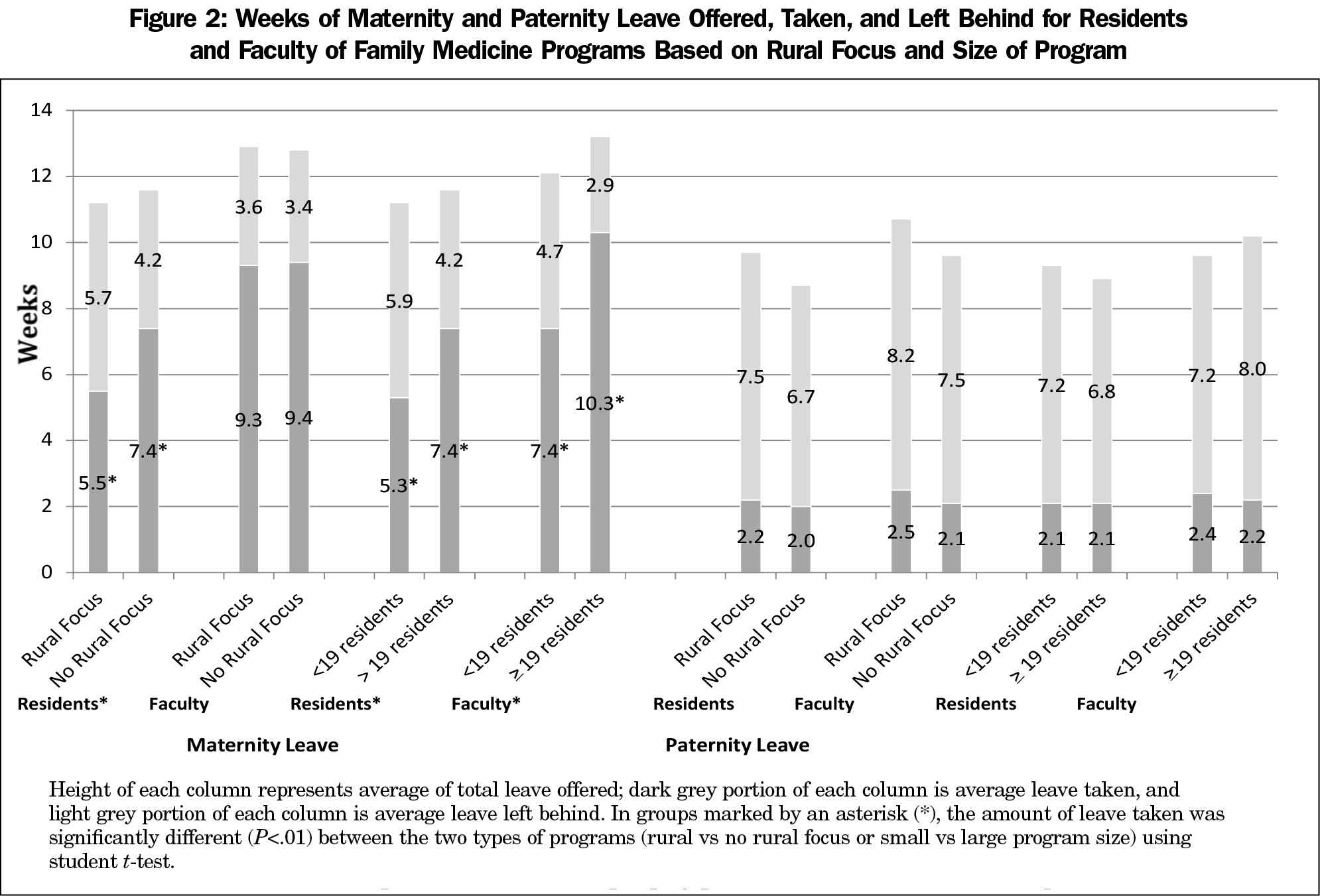

There was no significant difference in the amount of maternity leave offered to residents or faculty based on program size or rural focus. However, residency program size and rural focus were each significantly associated with the amount of maternity leave taken by residents; program size was also associated with the amount taken by faculty (Figure 2). Both residents and faculty at smaller programs took less total maternity leave (small program residents 5.3 weeks, faculty 7.4 weeks, P<.01; large program residents 7.4 weeks, faculty 10.3 weeks, P<.01). Similarly, residents at rurally-focused programs took less total maternity leave (rural program residents averaged 5.5 weeks, nonrural program 7.4 weeks, P<.01). Program size and rural focus did not correlate with the amount of paternity leave offered or taken by either group. Program director gender, percentage of female residents, and percentage of female faculty were not correlated with maternity or paternity leave offered or taken.

In regression analyses, program size predicted the amount of paid and total maternity leave taken by residents (β=1.2, P<.01 and β=1.3, P<.01, respectively), with residents at larger programs taking more leave. Rural focus was also independently predictive of the total maternity leave taken by residents, with residents at programs without a rural focus taking more leave (β=1.8, P<.01). The percentage of women faculty, percentage of women residents, and program director gender were not predictive of weeks of maternity leave. None of the variables examined were significantly associated with paternity leave.

Most residency programs (171/233; 73.4%) offered an at-home elective option for new parents. There was no relationship between the presence of an elective and size of the program, rural focus, program director gender, or percentage of women faculty or residents.

This study demonstrates wide variation in maternity and paternity leave policies among US FM residency programs. Notably, almost 30% of FM programs offered no paid maternity leave and almost 40% offered no paid paternity leave to residents or faculty. Although many programs supplement parental leave with at-home elective options for residents, our research demonstrates a surprising lack of universal support for parental leave among academic FM programs. This finding runs counter to the family orientation of our specialty and the fact that many residency and academic medicine programs and organizations have called for family-friendly parental leave policies for faculty and residents.3,16,24,29-31

By surveying FM residency program directors about both policies and actual leave taken by recent residents and faculty members, our study begins to illustrate the interplay between policy and culture petaining to parental leave. This is important, as policies need to be supported by institutional and specialty culture in order to effectively protect time for new parents. Based on our data, this is a valid concern, as many FM program directors reported that recent residents and faculty members took less paid parental leave than was offered. Although many factors contribute to decisions regarding time away from work, including financial constraints and specialty board-level policies that functionally limit available leave, the amount of paid leave left behind by residents was strongly correlated to that left behind by faculty within the same programs. This supports the concept that organizational culture, including modeling by faculty and the hidden curriculum, may at least partially impact these decisions.

Smaller and rurally-focused programs were at highest risk of residents taking less maternity leave than was offered, and faculty at smaller programs were also at higher risk of leaving maternity benefits behind. This may be understandable, as it is likely that smaller programs and rural programs have less depth of coverage for employee absences. However, parental leaves are usually predictable. Administrators and faculty of small and/or rural programs should be aware of this phenomenon, and should actively encourage cultural norms that support maternity benefits, as well as back-up coverage and protected and paid time through medical and family leave policies. This is particularly important because inadequate maternity leave may discourage women physicians from choosing and staying in rural communities for practice.32

For residents, the amount of leave permitted without making up time is determined by each medical specialty board; there is no ACGME policy on resident parental leave. The desire to avoid extending residency training (which can interfere with the start date of a subsequent job or fellowship) may motivate some residents to take less leave than offered.

Although they are not binding, professional society parental leave recommendations can also influence parental leave policies and specialty culture. For example, the American College of Surgeons recently suggested a minimum of 6-8 weeks of maternity leave and 6 weeks of paternity leave, recommending that surgeons should not pay practice overhead while on leave or be required to make up call.33 Currently, the AAFP does not recommend a specific duration for parental leave. A recommendation from our specialty society could support the development of more uniform and family-friendly policies.24

Our study has several important limitations. We depended on program directors to report policies and leave taken by recent residents and faculty. This method is subject to recall and reporting bias, and also reflects practices of only the most recent resident/faculty that have been eligible for leave in the program. Nonrespondents for the parental leave questions tended to be from smaller communities and have lower percentages of female faculty members than respondents, which could have impacted results. For analysis, all responses of >12 weeks were recoded to 13 weeks, which may have underrepresented the leave available at some programs. Finally, we were not able to ask questions about foster and adoptive parental leave policies because of the limited number of questions permitted by the CERA survey. Future studies could prospectively measure actual leave taken by new parents, could also explore differences in written policy between institutions, could qualitatively explore practical ideas to increase the amount of parental leave residents or faculty are able to take, especially in smaller or rural programs, or could explore whether inadequate faculty parental leave policies discourage residents from choosing academic or other careers.

Despite AAFP support for policies that encourage time away from work duties for new parents, there remains large variability in parental leave policies among FM programs, and variable benefit from the policies that do exist. FM residency programs should be aware of the many factors that influence resident and faculty comfort with taking time away from the workplace after the addition of a child, and should encourage an environment that supports new parents. The ACGME could also consider more strictly regulating parental leave policies and practices, in order to best support our resident and faculty workforce.

Acknowledgments

This study was presented at the following conferences:

NAPCRG Annual Conference, Montreal, Canada, November 2017; STFM Annual Spring Conference. Washington, DC, May 2018; Association of American Medical Colleges Annual Meeting—Learn, Serve, Lead, Austin, TX, November 2018.

References

- Hutchinson AM, Anderson NS III, Gochnour GL, Stewart C. Pregnancy and childbirth during family medicine residency training. Fam Med. 2011;43(3):160-165.

- Sandler BJ, Tackett JJ, Longo WE, Yoo PS. Pregnancy and Parenthood among Surgery Residents: Results of the First Nationwide Survey of General Surgery Residency Program Directors. J Am Coll Surg. 2016;222(6):1090-1096. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2015.12.004

- Blair JE, Mayer AP, Caubet SL, Norby SM, O’Connor MI, Hayes SN. Pregnancy and Parental Leave During Graduate Medical Education. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):972-978. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001006

- Sayres M, Wyshak G, Denterlein G, Apfel R, Shore E, Federman D. Pregnancy during residency. N Engl J Med. 1986;314(7):418-423. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJM198602133140705

- Carr PL, Gunn CM, Kaplan SA, Raj A, Freund KM. Inadequate progress for women in academic medicine: findings from the National Faculty Study. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2015;24(3):190-199. https://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2014.4848

- Borges NJ, Navarro AM, Grover AC. Women physicians: choosing a career in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2012;87(1):105-114. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31823ab4a8

- Edmunds LD, Ovseiko PV, Shepperd S, et al. Why do women choose or reject careers in academic medicine? A narrative review of empirical evidence. Lancet. 2016;388(10062):2948-2958. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01091-0

- Weiss J, Teuscher D. What Provisions Do Orthopaedic Programs Make for Maternity, Paternity, and Adoption Leave? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2016;474(9):1945-1949. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11999-016-4828-x PMID:27075331

- Berkowitz CD, Frintner MP, Cull WL. Pediatric resident perceptions of family-friendly benefits. Acad Pediatr. 2010;10(5):360-366. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.acap.2010.06.013

- O’Gurek DT, Pugno PA, Talley M. A sustainable family medicine academic workforce: a study of Pennsylvania residency faculty. Fam Med. 2012;44(8):545-549.

- Huerta MC, Adema W, Baxter J, et al. Fathers’ Leave and Fathers’ Involvement: Evidence from Four OECD Countries. Eur J Soc Secur. 2014;16(4):308-346. https://doi.org/10.1177/138826271401600403

- Nepomnyaschy L, Waldfogel J. Paternity leave and fathers’ involvement with their young children. Community Work Fam. 2007;10(4):427-453. https://doi.org/10.1080/13668800701575077

- Sarkadi A, Kristiansson R, Oberklaid F, Bremberg S. Fathers’ involvement and children’s developmental outcomes: a systematic review of longitudinal studies. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97(2):153-158. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1651-2227.2007.00572.x

- Department of Labor Policy Brief (2015): Paternity Leave, Why Parental Leave for Fathers is So Important for Working Families.

- Humphries LS, Lyon S, Garza R, Butz DR, Lemelman B, Park JE. Parental leave policies in graduate medical education: A systematic review. Am J Surg. 2017;214(4):634-639. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amjsurg.2017.06.023

- McPhillips HA, Burke AE, Sheppard K, Pallant A, Stapleton FB, Stanton B. Toward creating family-friendly work environments in pediatrics: baseline data from pediatric department chairs and pediatric program directors. Pediatrics. 2007;119(3):e596-e602. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2006-2397

- Davis JL, Baillie S, Hodgson CS, Vontver L, Platt LD. Maternity leave: existing policies in obstetrics and gynecology residency programs. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;98(6):1093-1098. https://doi.org/10.1097/00006250-200112000-00018

- MacVane CZ, Fix ML, Strout TD, Zimmerman KD, Bloch RB, Hein CL. Congratulations, you’re pregnant! now about your shifts . . . : the state of maternity leave attitudes and culture in EM. West J Emerg Med. 2017;18(5):800-810. https://doi.org/10.5811/westjem.2017.6.33843

- Hariton E, Matthews B, Burns A, Akileswaran C, Berkowitz LR. Pregnancy and Parental Leave among Obstetrics and Gynecology Residents: Results of a Nationwide Survey of Program Directors. Am J of Obstet Gynecol. 2018;219(2): 199.e1-199.e8. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2018.04.017

- Rose SH, Burkle CM, Elliott BA, Koenig LF. The impact of parental leave on extending training and entering the board certification examination process: a specialty-based comparison. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(11):1449-1453. https://doi.org/10.4065/81.11.1449

- Morris LE, Lindbloom E, Kruse RL, Washington KT, Cronk NJ, Paladine HL. Perceptions of Parenting Residents Among Family Medicine Residency Directors. Fam Med. 2018;50(10):756-762. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2018.978635

- Banks JW III, Harrell PL. Mother-child development elective: a formal educational maternity leave. Fam Med. 1992;24(5):375-377.

- Morris L, Cronk NJ, Washington KT. Parenting During Residency: Providing Support for Dr Mom and Dr Dad. Fam Med. 2016;48(2):140-144.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Parental Leave During Residency Training. http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/parental-leave.html. Accessed October 4, 2016.

- Gunn CM, Freund KM, Kaplan SA, Raj A, Carr PL. Knowledge and perceptions of family leave policies among female faculty in academic medicine. Womens Health Issues. 2014;24(2):e205-e210. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2013.12.008

- Itum DS, Oltmann SC, Choti MA, Piper HG. Access to Paid Parental Leave for Academic Surgeons. J Surg Res. 2019;233:144-148.

- Mainous AG III, Seehusen D, Shokar N. CAFM Educational Research Alliance (CERA) 2011 Residency Director survey: background, methods, and respondent characteristics. Fam Med. 2012;44(10):691-693.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. Effective July 1, 2016. http://www.acgme.org/portals/0/pfassets/programrequirements/120_family_medicine_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed April 15, 2018.

- Choo EK, Kass D, Westergaard M, et al. The Development of Best Practice Recommendations to Support the Hiring, Recruitment, and Advancement of Women Physicians in Emergency Medicine. Acad Emerg Med. 2016;23(11):1203-1209. https://doi.org/10.1111/acem.13028

- Greenfield NP. Maternity and medical leave during residency: time to standardize? Int J Womens Dermatol. 2015;1(1):55. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijwd.2014.12.009

- American Congress of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Statement of Policy as Issued by the Executive Board of ACOG regarding Paid Parental Leave. https://www.acog.org/-/media/Statements-of-Policy/Public/92ParentalLeaveJuly2016.pdf?. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- Hustedde C, Paladine H, Wendling A, et al. Women in rural family medicine: a qualitative exploration of practice attributes that promote physician satisfaction. Rural Remote Health. 2018;18(2):4355. https://doi.org/10.22605/RRH4355 PMID:29665695

- American College of Surgeons. Statement on the Importance of Parental Leave. February 24, 2016. https://www.facs.org/about-acs/statements/84-parental-leave. Accessed April 15, 2018.

There are no comments for this article.