Background and Objectives: Facilitation is common in the era of practice transformation. Much of the literature on practice facilitators focuses on the role of external facilitators who come into a practice to aid in practice transformation efforts. Our study sought to better understand the attributes of exemplary facilitators.

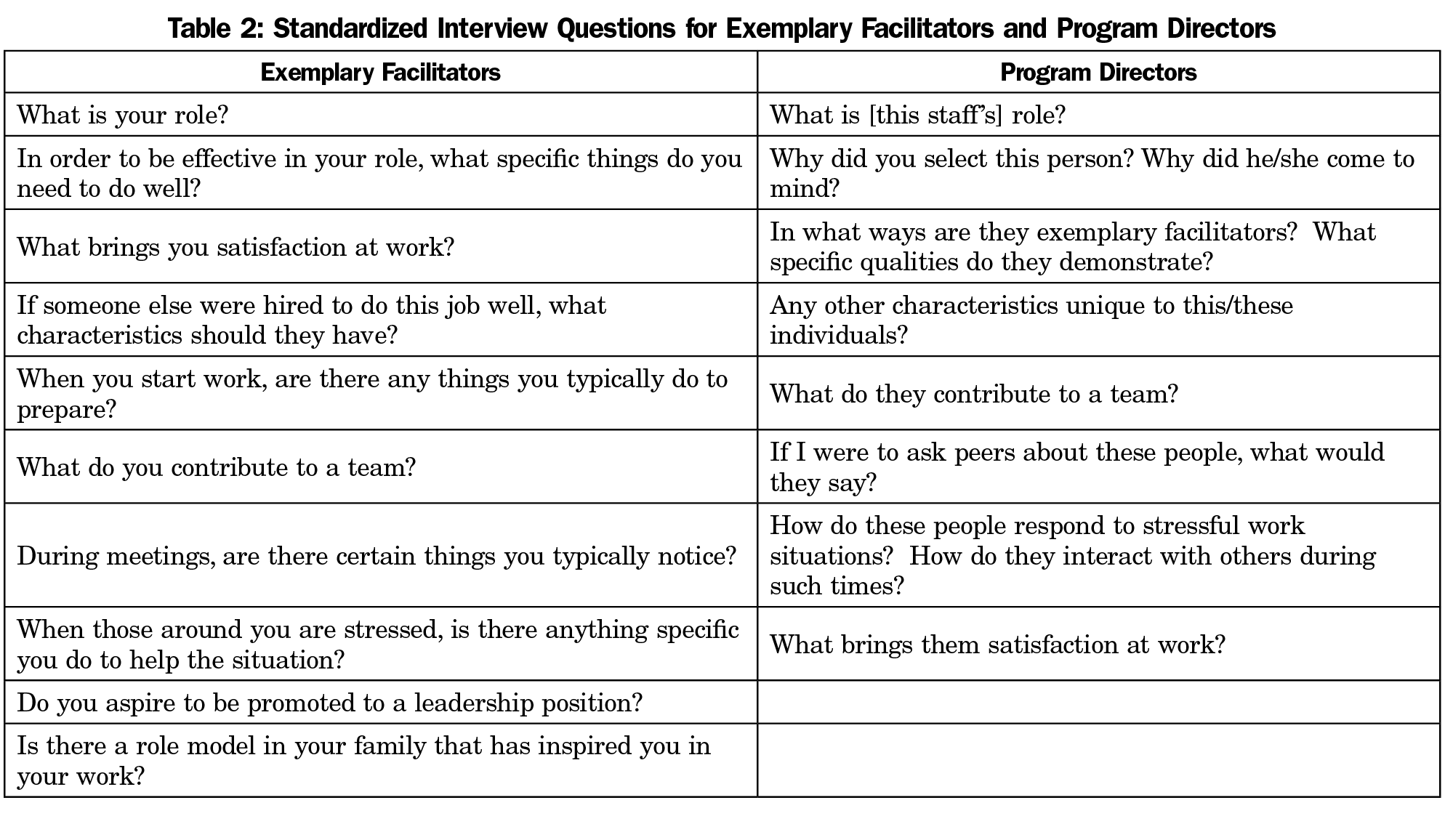

Methods: We conducted 10 structured interviews in four family medicine residencies.

Results: Program directors easily identified internal staff who serve informally as exemplary facilitators. Despite varying jobs, they possess seven identifiable attributes within three broad domains: task orientation, relational skills, and emotional intelligence.

Conclusions: Given the increasing cost of practice transformation and the finite resources in many clinics, this study can help leaders identify current employees best suited for facilitation.

In health care literature, the term “practice facilitator” describes someone who assists clinicians in practice transformation projects.1-8 These facilitators commonly work toward improving the delivery of clinical interventions, particularly preventive services9-10; facilitating research and quality improvement (QI) projects11-12; and implementing health information technology.

Historically “facilitation” described the abstract idea of making something “easy or easier.”13 This concept of facilitation, grounded in the 1980’s literature on nursing evidence-based practice, includes a varying set of characteristics and qualifications held by people who make things easier.4,7,9,14-16 Specifically, researchers have described facilitators as being empathic, sensitive, flexible, resilient, authentic, and passionate about their work.3,14 They have been called “agents of change” and “cross-pollinators of good ideas.”15 Not typically in formal leadership roles, they are thought to be information-givers, trainers, researchers, and advisors who possess project management and interpersonal communication skills to move ideas forward to fruition.3,7,11 Capturing both the personal attributes and the professional competencies involved in facilitation, Harvey et al16 in 2002 described the concept of facilitation on a continuum. The task end of the continuum is characterized by practical, task-driven activities such as administering and supporting QI projects. In contrast, the holistic end of the continuum focuses on relational and communication skills such as developing and empowering individuals and teams and improving the existing culture.

In 2012, Baskerville and colleagues17 conducted a systematic review and meta-analysis of practice facilitation and found moderate effect sizes favoring practice facilitation across the studies included. Bitton proposed that sustained facilitation is one of the “few parsimonious enablers and tenets of practice transformation.”18 As more primary care practices undergo practice transformation, an increasingly important area of research is adeptly finding, selecting, and preparing the right people to take on the facilitator role.6,17,18 Further understanding of the attributes of effective facilitators is needed to ensure the right people are selected and empowered to do this work. While research has helped illuminate some of the roles of practice facilitators, descriptions of the personal attributes of facilitators are limited.2,3,6,7,11,19,20 Much research focuses on external practice facilitators who, coming into an organization from the outside, may need different skills to work with an unfamiliar group.1,21 The goal of this project was to explore attributes of internal staff identified by family medicine residency directors as “people in the office or clinic who make things easier.” We have termed these people “exemplary facilitators” based on the literature on facilitation. This information may help leaders proactively identify staff members who would make effective facilitators, who can use their strengths for practice transformation and other activities to enhance the overall success of the practice.

Interviews took place at four family medicine residency programs in Colorado, all of which had been part of a multiyear statewide practice transformation initiative. Four program directors were each tasked with identifying individuals who were not in a formal leadership position, nor necessarily in a practice transformation role, but who were “effective at getting things done.” They were to recommend candidates who made activities “flow more easily with good outcomes.” Three program directors suggested two people and one director suggested one person for a total of seven participants. The suggested participants were contacted by email and phone to explain the project. All seven employees agreed to participate in individual video-recorded interviews. Three of the four program directors were also interviewed to provide additional perspectives on the selected employees’ skills and attributes. One director changed jobs and therefore was unable to participate. The Institutional Review Board of the University of Colorado Health exempted this study from formal review.

Data Collection and Analysis

Data were collected and analyzed in three phases. First, to increase consistency, one author conducted all ten videotaped interviews using a standardized set of open-ended questions aimed at identifying characteristics and attributes that contribute to effective facilitation (Table 1). Second, an iterative thematic analysis was conducted of the video recordings to examine patterns (themes) within the data.22 The first author reviewed all raw data and created an initial coding framework that evolved as the analysis proceeded. Initial codes were assigned to all characteristics discussed by interviewees. Those characteristics described in at least 50% of the interviews were grouped; descriptive labels were created by the authors to describe the characteristics. The second author independently reviewed the video-recorded interviews to validate the coding framework and make any refinements. A comparison of the authors’ independent ratings revealed an agreement ratio of 89%. Lastly, excerpts clustered by proposed themes were shown to six independent groups to evaluate the proposed descriptive theme labels and come to consensus on whether the terms being used by the researchers accurately named the characteristics being discussed by interviewees. The final agreed-upon themes were compared to existing literature on facilitation and are presented here.

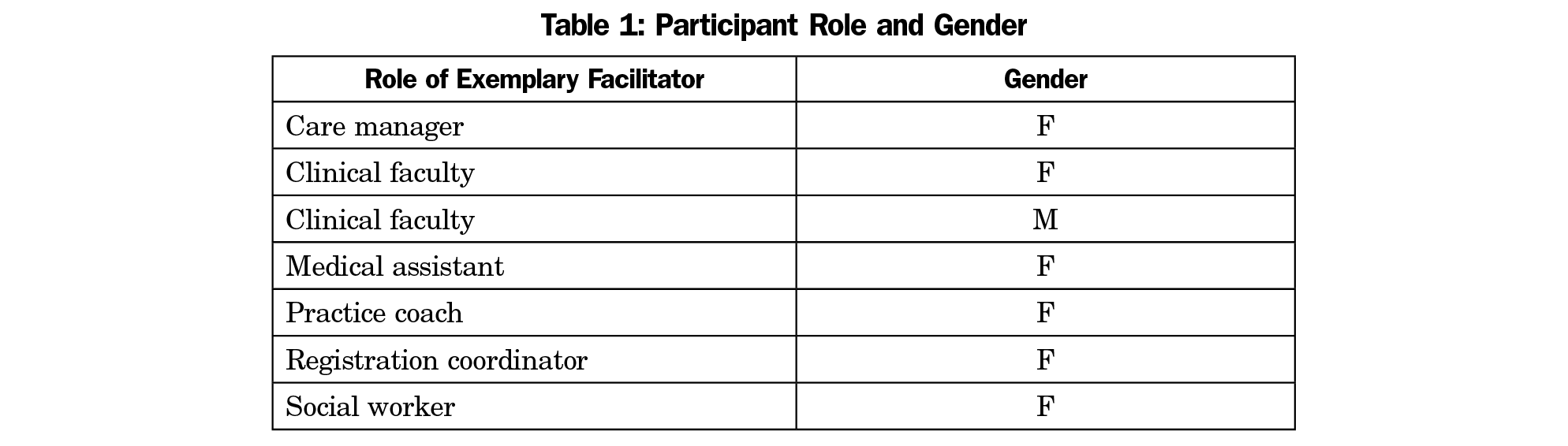

We completed interviews with three program directors and seven staff from four family medicine residency programs. The mean length of the interviews was 19 minutes with a range of 12:53 to 27:52. Job titles and demographic information about the participants are listed in Table 1.

We found that program directors confidently identified staff fitting the description of “making things flow more smoothly.” Program directors described these staff in ways consistent with the literature on facilitation despite not being prompted to identify practice facilitators more specifically. These exemplary facilitators were found to possess skills grouped in three general domains: task orientation, relational skills and support, and emotional intelligence.

Task Orientation

Consistent with the Harvey et al continuum of facilitation, our thematic analysis revealed personal attributes on the task side of the facilitation spectrum, including (1) taking action and (2) being organized/detail-oriented.16 Our exemplary facilitators commonly described taking action in contrast to abstract thinking or creating a vision; they were inclined to break down a large project into concrete steps and begin. Program directors reflected that these exemplary facilitators were the doers who “kept the momentum going.” They were described as eager to take the next steps and move projects forward. Participant comments that typified this attribute included:

I think I’m a very practical person at the core; what it comes down to is, okay, what needs to be done? How are we going to do it?

I tend to be the person who wants to work hard on a team; after the ideas are discussed, I’m the one who volunteers to start.

Sometimes I’ll throw this out: “What’s the action plan?” because we’ve got to do something now.

The ability to take a task and get it done, that’s how I’m known; if they want something done and done quickly, they typically task that to me; that’s my personality, I’m a doer.

Also within the task-oriented domain, exemplary facilitators were found to have systems in place to track details, organize information, and plan ahead. Program directors noted the facilitator’s ability to act was rooted in being organized, though the program directors did not refer to any specific methods of organization. The exemplary facilitators easily articulated their specific organizational strategies to track projects and prioritize activities. All but one reflected on a list-keeping strategy that helps them organize and track details. The act of maintaining an updated to-do list was a hallmark of the exemplary facilitator’s self-described effectiveness.

Relational Skills and Support

Consistent with the holistic side of the Harvey et al continuum,16 coding revealed a broad domain of “relational skills and support” which was further delineated into the subattributes of (1) positive attitude and enthusiasm, (2) caring and compassion, and (3) a sense of humor.

Program directors described their exemplary facilitator staff as bringing boundless enthusiasm and a positive presence to group projects. The participants actually took this description one step further and articulated not only a natural positivity and enthusiasm, but also a decided enthusiasm throughout work and specific projects. They brought enthusiasm to the team on purpose “to keep things light” because “enthusiasm can go a long way for helping other people get engaged.” One noted that he/she tries “to bring fun into work, to bring the energy level up so people are as happy as can possibly be.”

Caring and compassion was evident in the facilitators’ and the program directors’ descriptions. Program directors noted the exemplars were considerate and compassionate staff who “really enjoy helping other people, whether that’s patients or coworkers.” One noted they “care a lot about their colleagues and their patients.” The exemplary facilitators’ comments included the following:

Being friendly and having good working relations with the staff helps a lot.

Just making sure that everybody knows we’re on the same team, and has a feeling of what it’s like to be on the same team, not just a concept; I have a feeling of pride in the work that everybody has.

Consistent with enthusiasm, these exemplary facilitators also described having senses of humor related to the work at hand. Some explicitly stated they use wit or tell jokes to lighten tense meetings. The facilitators described themselves as goofy, funny, or light-hearted. There was a distinct recognition from both program directors and facilitators that caring for patients is challenging work. The humor described and the examples given were consistently respectful, not at the expense of patients or other parties. One program director noted that the exemplary facilitators at their office “are wonderful with their sense of humor; it’s hard working in a clinic and at the end of a long day, both have a great sense of humor and I find myself laughing along with them; they both love a good laugh.” One facilitator commented that “I crack little jokes because this is a hard job for all of us.”

Emotional Intelligence

Two characteristics relate to the concept of emotional intelligence: (1) empathy/awareness of others’ feelings and needs and (2) emotional self-management.23 Based on participant descriptions, these attributes enable them to keep processes moving even when emotions may run high. Exemplary facilitators described the ability to read a room, empathize with others, and change their own behavior to impact a situation, such as a team meeting. They pick up on emotions early and address them in a constructive way, for example by inviting individuals to share their thoughts, identifying differences of opinion, or using humor to reduce tension. By staying calm (self-management), they model effective coping and defuse frustration. These characteristics may be closest to the conventional definition of facilitation skills in the context of running meetings successfully.

Program directors were clearly aware of the level of empathy their exemplary facilitators have in group situations. They were seen as specialists in being “perceptive to the stress of the clinic.” One program director mentioned important listening skills “coupled with a great ability to reframe what they’ve heard, to ask questions and inquire”. Most exemplary facilitators did not use the words emotional intelligence (EI) or empathy specifically but each was able to describe a constellation of skills or actions that typify empathy and EI. One commented “I pick up, emotionally, on where the other people in the room are, quicker than other people.” Some cited awareness of body language saying that “oftentimes in groups I may notice when someone is checked out based on their body language” or “watching body language… is important; being able to watch who’s engaged and who isn’t.” One named empathy specifically; stating “In meetings with my team I pick up their emotions or the vibes they are putting off; I feel like I pick up on others’ stress pretty easily; I’m a fairly empathetic person.”

Exemplary facilitators and program directors alike described a measured response to emotions, an emotional control important for facilitation. Program directors stated he/she “does all sorts of things that defuse the stress of the clinic” and “she’s kind of unflappable; it’s hard to tell when she’s stressed.” The exemplary facilitators were described as being calm and able to weather the storms of team meetings and patient care. This outwardly calm demeanor was described as thoughtful and mindfully constructed by the facilitators. One program director noted that the facilitators “think very clearly about how their actions and their words come across to others and how decisions will impact others.” They see their role as remaining calm and being objective about what is going on. One noted that when people are stressed “that’s when I actually feel I’m at my best, when I can step in and help them get passed it.” They described the ability to deescalate tense situations by mellowing their voice, remaining calm, and having a “deep relaxed patience.”

Our results suggest that certain staff in family medicine residencies are recognized by program directors as bringing value to teams, projects, and processes by making things easier for others. In our sample, these exemplary facilitators possess seven identifiable attributes within three broad domains: task orientation, relational skills, and emotional intelligence. These attributes are consistent with previous research on facilitation skills and personal attributes of facilitators. However, our attributes were derived from interviewing the facilitators themselves and the leaders who are closely familiar with their work. It is important to note that a broad definition of facilitation was used in this study. The sample was drawn from all clinic employees and was not limited to practice facilitators. The results, therefore, pertain to a broader range of people in the clinical setting who make things easier for others.

The exemplary facilitators in this study were not in formal leadership or management positions; the majority did not aspire to leadership roles. Only one was functioning as a practice facilitator. They all expressed a deep commitment to the task- and relationship-oriented mix of work in their current roles and were participating on clinic and/or quality improvement teams. The results may help program directors and other clinic leaders identify exemplary facilitators in existing personnel, lessening some of the estimated costs of practice facilitation.24 Strategic placement on teams and special projects would enable such staff the opportunity to apply their facilitation skills while remaining with their primary job duties. Obviously, assigning additional duties to these natural facilitators may be challenging due to institutional regulations and the importance of not overloading and burning out these employees. However, a heightened awareness of the exemplary facilitators embedded in the clinic workforce may enable leaders to strategically place these employees to increase their satisfaction while enhancing transformation efforts. These results also can be used when hiring new staff. While it is challenging to assess personal attributes such as detail-orientation and empathy during an interview, these characteristics may be evident in application documents and may be assessed by asking specific questions of an applicant.

These findings are relevant to academic practices. The educational experience of residents will be improved if clinical and quality improvement teams are productive and functional. The strategic presence of in-house exemplary facilitators on teams can enhance the clinical learning environment. Additionally, specific information about effective facilitators can be integrated into the curriculum. This information can enhance residents’ facilitation skills as well as sharpen their recognition of exemplary facilitators in their clinical environment. Their educational experience with team-based care and awareness of the value of skilled facilitation will better prepare them for future practice.

The characteristics of the exemplary facilitators in this study share some commonalities with successful leaders and managers. Examples are showing a positive attitude, compassion for the organization, and emotional self-management. Yet several of the personal attributes of the facilitators differ from core characteristics described in leadership and management literature. According to the seminal works of Kouzes and Posner25 and Kotter26 successful leaders create a vision, align and inspire people to follow that vision, get the right people on board, and enable others to act. Successful managers provide structure to implement the plan by supervising people, managing day-to-day operations, communicating standards, and holding staff accountable. The majority of facilitators in this sample stated they were not interested in leadership or management positions. They were not interested in creating a vision or supervising others. Rather, they gained satisfaction from working on specific projects, willingly organizing timelines and details, were skilled at finding ways to solve practical problems, were in tune with others on their team, and took pride in the group accomplishments. While there is some overlap with the characteristics of effective leaders and managers, some attributes of facilitators are distinct (Figure 1), suggesting all three roles are helpful in successful primary care practice transformation.

An interesting and relevant question is whether the characteristics of these exemplary facilitators can be learned through training. The continuum of facilitation described by Harvey et al,16 is useful to address this question. Task-specific skills, such as strategies and tools (eg, the plan-do-study-act [PDSA] cycle) for managing quality improvement projects or guiding practice transformation efforts, are often learned by staff during clinic- and system-wide transformation programs. However, holistic facilitation skills, including the personal attributes identified in this study, are likely inherent traits. In his book Good to Great, Jim Collins posits that the right person for a job has more to do with character traits and innate capabilities than with specific knowledge, background, or skills.27 Efforts to teach characteristics such as positivity, empathy, detail-orientation, and sense of humor would be difficult and, even if trainees adopted such new skills, they may not be sustained. However, to be effective, a practice facilitator may not require all the personal attributes identified in this study. Individuals can use their inherent facilitation-related strengths and proactively team up with others who have complementary strengths. For example, one participant stated that his organizational skills were lacking but he sought out team members with that strength. Yet this select sample of exemplary facilitators possessed a similar set of personal attributes that made them stand out from others. The program directors recognized this set of skills and described them in detail. One can hypothesize that individuals with more of the personal attributes identified in this study will be more successful in a facilitator role than those with fewer of the identified characteristics. This is an area for further research.

A major limitation of this study is the small sample size and the lack of diversity in the study sample. Therefore, caution is warranted when generalizing the results. The seven exemplary facilitators were from a limited geographical area and all were Caucasian. Six of seven (86%) were female. Further research is warranted to understand the personal attributes of exemplary facilitators in settings with more racial, ethnic, and gender diversity.

Exemplary facilitators share important attributes that enable them to be effective at getting projects done and making processes easier in situations that call for collaboration. They may not have been hired to be practice facilitators, however they can be identified and perhaps empowered to serve in that capacity. This study brings up additional questions, such as how to consistently identify internal staff who are effective facilitators and how to reward, support, and retain such people. This information will be valuable in the search for sustained facilitation in the ongoing work of practice transformation and clinical effectiveness.

References

- Nutting PA, Crabtree BF, Stewart EE, et al. Effect of facilitation on practice outcomes in the National Demonstration Project model of the patient-centered medical home. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(suppl 1):S33-S44, S92. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1119

- Nagykaldi Z, Mold JW, Aspy CB. Practice facilitators: a review of the literature. Fam Med. 2005;37(8):581-588.

- Cranley LA, Cummings GG, Profetto-McGrath J, Toth F, Estabrooks CA. Facilitation roles and characteristics associated with research use by healthcare professionals: a scoping review. BMJ Open. 2017;7(8):e014384. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2016-014384

- Buscaj E, Hall T, Montgomery L, et al. Practice facilitation for PCMH implementation in residency practices. Fam Med. 2016;48(10):795-800.

- Taylor EF, Machta RM, Meyers DS, Genevro J, Peikes DN. Enhancing the primary care team to provide redesigned care: the roles of practice facilitators and care managers. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(1):80-83. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1462

- Lessard S, Bareil C, Lalonde L, et al. External facilitators and interprofessional facilitation teams: a qualitative study of their roles in supporting practice change. Implement Sci. 2016;11(1):97. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-016-0458-7

- Harvey G, Lynch E. Enabling continuous quality improvement in practice: the role and contribution of facilitation. Front Public Health. 2017;5:27. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpubh.2017.00027

- Liddy CE, Blazhko V, Dingwall M, Singh J, Hogg WE. Primary care quality improvement from a practice facilitator’s perspective. BMC Fam Pract. 2014;15(1):23. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2296-15-23

- Donahue KE, Halladay JR, Wise A, et al. Facilitators of transforming primary care: a look under the hood at practice leadership. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(suppl 1):S27-S33. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1492

- Due TD, Kousgaard MB, Waldorff FB, Thorsen T. Influences of peer facilitation in general practice - a qualitative study. BMC Fam Pract. 2018;19(1):75. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-018-0762-1

- Kotecha J, Han H, Green M, Russell G, Martin MI, Birtwhistle R. The role of the practice facilitators in Ontario primary healthcare quality improvement. BMC Fam Pract. 2015;16(1):93. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12875-015-0298-6

- McHugh M, Brown T, Liss DT, Walunas TL, Persell SD. Practice facilitators’ and leaders’ perspectives on a facilitated quality improvement program. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(Suppl_1):S65-S71. https://doi.org/0.1370/afm.2197.

- The American Heritage College Dictionary. 3rd ed. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co; 1993.

- Kitson A, Harvey G, McCormack B. Enabling the implementation of evidence based practice: a conceptual framework. Qual Health Care. 1998;7(3):149-158. https://doi.org/10.1136/qshc.7.3.149

- Cook R. Primary care. Facilitators: looking forward. Health Visit. 1994;67(12):434-435.

- Harvey G, Loftus-Hills A, Rycroft-Malone J, et al. Getting evidence into practice: the role and function of facilitation. J Adv Nurs. 2002;37(6):577-588. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2002.02126.x

- Baskerville NB, Liddy C, Hogg W. Systematic review and meta-analysis of practice facilitation within primary care settings. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(1):63-74. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1312

- Bitton A. Finding a parsimonious path for primary care practice transformation. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(suppl 1):S16-S19. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2234

- Berta W, Cranley L, Dearing JW, Dogherty EJ, Squires JE, Estabrooks CA. Why (we think) facilitation works: insights from organizational learning theory. Implement Sci. 2015;10(1):141. https://doi.org/10.1186/s13012-015-0323-0

- Due TD, Thorsen T, Waldorff FB, Kousgaard MB. Role enactment of facilitation in primary care - a qualitative study. BMC Health Serv Res. 2017;17(1):593. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12913-017-2537-0

- Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Nutting PA, Stange KC, Jaén CR. Primary care practice development: a relationship-centered approach. Ann Fam Med. 2010;8(suppl 1):S68-S79, S92. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1089

- Srivastava P, Hopwood N. A practical iterative framework for qualitative data analysis. Int J Qual Methods. 2009;8(1):76-84. https://doi.org/10.1177/160940690900800107

- Goleman D. Emotional Intelligence: Why it can Matter More than IQ. New York: Bantam Books; 1995.

- Culler SD, Parchman ML, Lozano-Romero R, et al. Cost estimates for operating a primary care practice facilitation program. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(3):207-211. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1496

- Kouzes JM, Posner BZ. The Leadership Challenge. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 2007.

- Kotter JP. Leading Change. Boston: Harvard Business Review Press; 1996.

- Collins JC. Good to Great: Why Some Companies Make the Leap ... and Others Don’t. New York, NY: Harper Business; 2001.

There are no comments for this article.