Background and Objectives: Implicit bias often affects patient care in insidious ways, and has the potential for significant damage. Several educational interventions regarding implicit bias have been developed for health care professionals, many of which foster reflection on individual biases and encourage personal awareness. In an attempt to address racism and other implicit biases at a more systemic level in our family medicine residency training program, our objectives were to offer and evaluate parallel trainings for residents and faculty by a national expert.

Methods: The trainings addressed how both personal biases and institutional inequities contribute to structural racism, and taught skills for managing instances of implicit biases in one’s professional interactions. The training was deliberately designed to increase institutional capacity to engage in crucial conversations regarding implicit bias. Six months after the trainings, an external evaluator conducted two separate 1-hour focus groups, one with residents (n=18) and one with program faculty and leadership (n=13).

Results: Four themes emerged in the focus groups: increased awareness of and commitment to addressing racial bias; appreciation of a safe forum for sharing concerns; new ways of addressing and managing bias; and institutional capacity building for continued vigilance and training regarding implicit bias.

Conclusions: Both residents and faculty found this training to be important and empowering. All participants desired an ongoing programmatic commitment to the topic.

More than a decade since the Institute of Medicine’s (IOM) Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care report highlighted that racial disparities are due in part to health care providers’ own biases, health disparities have persisted or worsened for some groups.1-3 Both individual and organizational biases play a role in perpetuating health disparities along dimensions such as race/ethnicity, age, sexual orientation, gender, and socioeconomic status.1,4 These biases, when acted on without an individual’s intentional control, are called implicit bias, and stem from automatic cognitive shortcuts that allow us to efficiently interpret stimuli by categorizing them in manageable bits. These instantaneous cognitive processes are more likely to be triggered in stressful situations when efficient decision-making is required, such as commonly occurs in medicine.5

Most studies attempting to address implicit bias in health care strive to increase awareness of individual biases through self-assessments (eg, Implicit Association Test).6-8 Several strategies have been suggested for individuals to act on specific biases once they are recognized, including conceptualizing bias as a habit of mind,8-9 individuating,10 and perspective-taking.11 Curricula on racism training have depended on pedagogical models that aim to improve individuals’ awareness of cultural differences, self assessments and technical skills, or opportunities for self-reflection. These approaches emphasize awareness and action on an individual rather than at a systemic level. For enduring change, there is a need for approaches that act as catalysts for systemic change.12

In an era of increasing tension regarding race and racism, trainees are looking to faculty for direction. How faculty engage in these difficult conversations with learners, as well as broader communities and institutions, is important. There is a need for a health professionals curriculum that will move beyond simply identifying implicit biases through self-reflection to (a) provide insight into how such insidious biases perpetuate institutional inequities and potentially exacerbate structural racism,13 and (b) empower health care professionals with skills for managing instances of racism and other implicit biases in their professional lives. The objective of this multimethod study was to evaluate participant experience with a parallel curriculum we simultaneously delivered to University of Minnesota North Memorial Family Medicine Residency Program residents and faculty (Minneapolis, MN) that aimed to meet these goals.

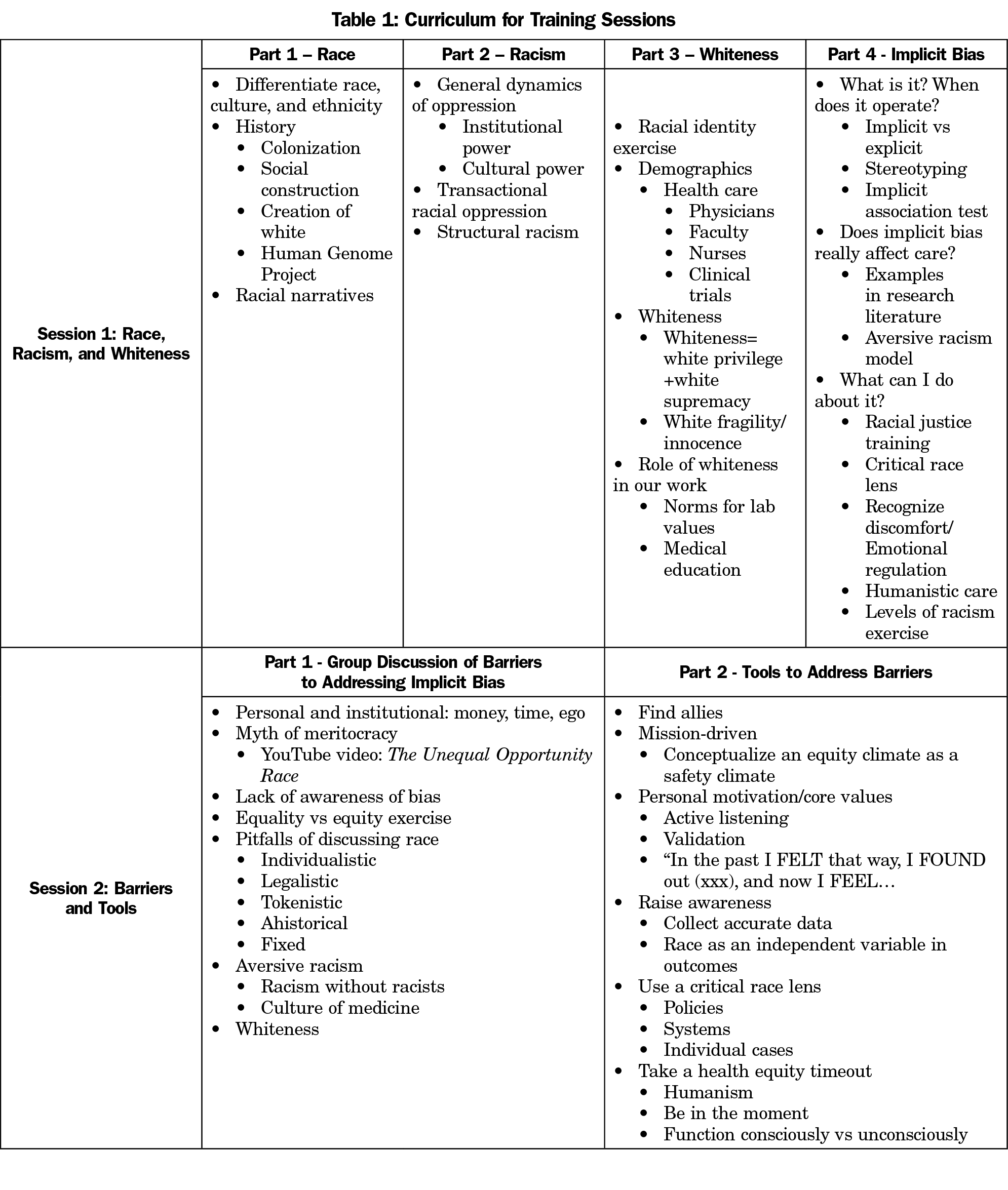

Our curriculum was based on a training module for residents that employs a transformative learning framework to address issues of race, racism, and “whiteness” (the overwhelming presence of white centrality and normativity in our society).14 Besides providing opportunities for individual level self-reflection, our curriculum emphasized engagement in critical dialogue with system factors involved in institutionalized racism. We broadened our training approach by (a) offering two 60 to 90-minute parallel workshops for residents and faculty, focusing on both patient care and teaching, and (b) incorporating more practical, applied recommendations for how to address implicit bias in practice. Training sessions were led by a national expert on implicit bias, and involved group discussion and reflection (Table 1). Anonymous satisfaction surveys were completed immediately after the second training (response rate=100%).

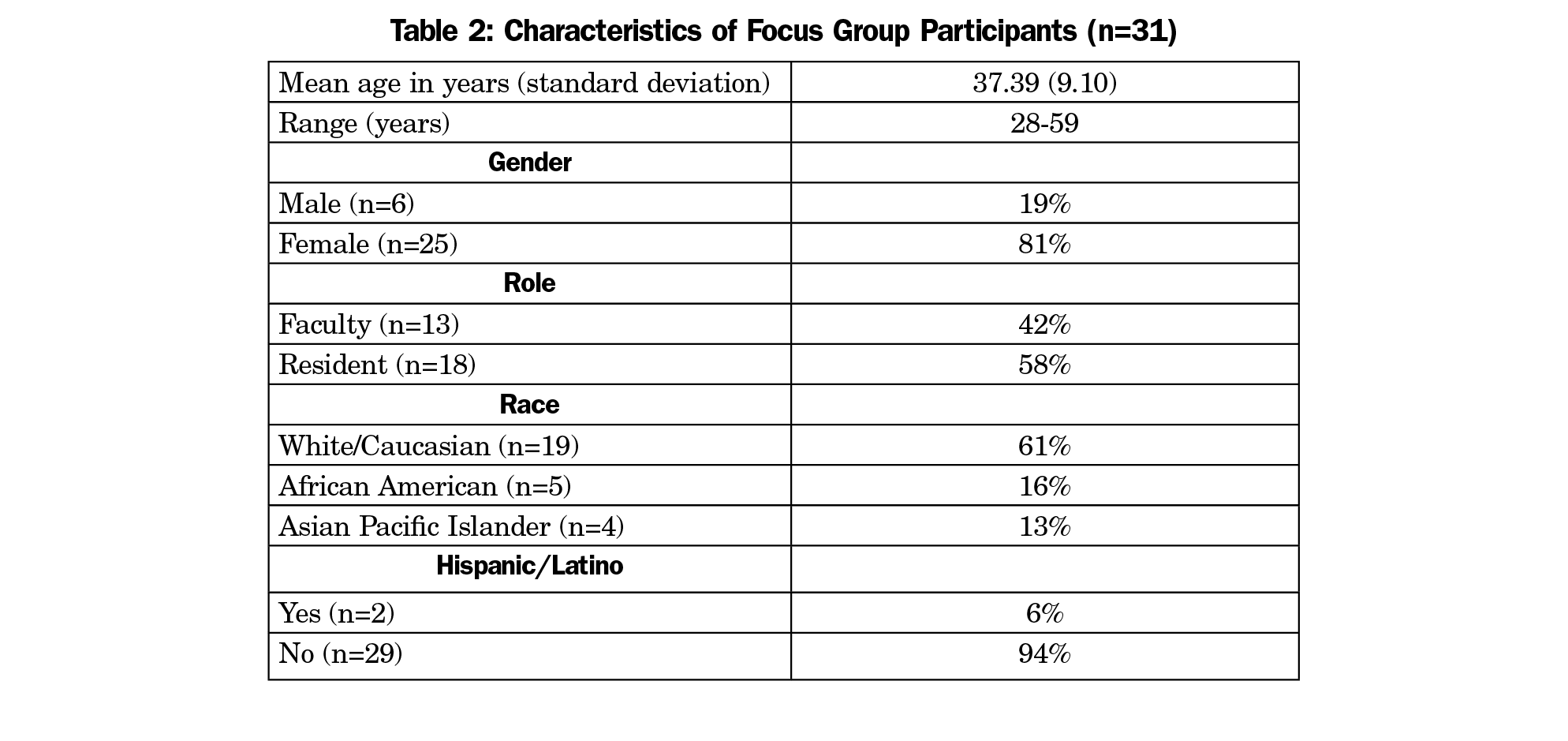

Recognizing that measuring implicit bias and the change in bias is problematic,15 we opted to primarily study our intervention qualitatively. Six months after the trainings, an external evaluator conducted two separate 1-hour focus groups—one with residents and one with faculty. The groups were conducted during weekly faculty meetings and resident meetings, both in March, 2018. Demographics of participants are in Table 2. Both groups followed the same semistructured interview protocol of five questions. These questions were determined before the focus group, and were codeveloped by the research team and an independent external evaluator with expertise in evaluation of programs that advance social change within complex systems. The questions, guided by a formative evaluation approach, related to participants’ experiences within the training, impacts of the training on individual roles and on the broader residency program, and areas for growth related to implicit bias.

The external evaluator analyzed the data using a phenomenological approach to further understand experience with the curriculum, using MaxQDA software. Data were coded using an inductive approach by identifying emerging themes and key points in the transcripts. Upon completion of coding of the second transcript (focus group 2), the full coding scheme was again applied to the first transcript (focus group 1) to achieve thematic saturation. The University of Minnesota Institutional Review Board reviewed the project and deemed it exempt.

Participants reported high levels of satisfaction with the training on the anonymous surveys completed at the second training session, with 88% of residents describing it as excellent (5/5 on a Likert scale) and 13% as very good (4/5). Similarly 100% of faculty reported they would strongly recommend the training to other family medicine residency programs, with almost all noting the training will help them as providers, preceptors, and community advocates.

Four overarching themes emerged from the focus groups. Exemplar quotations are shown in Table 3.

Increased Awareness of and Commitment to Addressing Racial Bias

Many participants reported that the training increased their awareness of racial bias, especially biases specific to medicine. Participants universally committed to increasing their awareness of racism and managing racial bias, both individually and as a program.

Safe Forum for Sharing Concerns

Participants in both focus groups expressed feeling safe sharing concerns with one another, noting the trainings strengthened their existing culture of open and safe communication. Residents reported feeling less comfortable going to faculty with their concerns about biases, noting worry about how such disclosures would be handled.

Implementing New Ways of Addressing and Managing Bias

Some participants reported they used new practices to address racial bias after the trainings. Some faculty members are collaborating with the larger affiliated hospital system to advance health equity work, asking for health equity officers and staff training on implicit bias. Some residents shared that the trainings provoked reflection regarding how their racial biases may affect how they choose treatment plans for patients. Since the training, several have been deliberately moderating that bias by challenging their decision making and assumptions.

Institutional Capacity Building: Iterative Trainings and Continued Vigilance

Both groups emphasized the importance of ongoing trainings and dialogue about implicit bias, resulting in the issue being part of a program’s culture rather than a one-time training. Both groups highlighted the importance of continued vigilance and transparency in these efforts, noting the real challenges in this work.

There is no single magic bullet approach that would eradicate implicit bias; residencies need to cultivate learning communities where difficult issues like implicit bias will be openly discussed. Participants indicated our training created a safe forum for sharing ideas, while recognizing the need for iterative learning and maintaining transparency in addressing implicit bias. Although participants learned skills regarding how to address racism, some wanted ongoing support for assertively addressing incidents of implicit bias.

Replication of this training and evaluation in other settings will allow comparison of findings; in so doing, contextual factors should be considered, including power dynamics inherent in residency programs. Institutions must include mechanisms to navigate these power imbalances, empowering those with less perceived power to feel comfortable sharing their experiences and perceptions. For example, dedicating time in meetings attended by both residents and faculty to discuss implicit bias together has the potential to open communication and facilitate appreciation of everyone’s shared commitment to this topic.

Limitations of this study include a sample of 31 people from a single institution and the fact that not all focus group participants attended both training sessions due to scheduling challenges. While our focus groups were conducted 6 months after the trainings, indicating lasting effects, sustained enduring effects are difficult to predict. We are hopeful that continued programmatic vigilance and each person’s ongoing journey regarding overcoming our biases will increase our institutional capacity and anchor ongoing work.

Acknowledgments

The authors received a Herz Faculty Development Award from the University of Minnesota in support of this project.

The authors thank Renee Crichlow, MD, Erica Gathje, MD, Tanner Nissly, DO and Michael Wootten, MD, for their support of this project.

References

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR, eds. Unequal treatment: Confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. Washington, DC: Press; 2003.

- US Department of Health and Human Services. 2016 National Healthcare Disparities Report. October 2017. AHRQ Pub. No. 17-0001. https://www.ahrq.gov/research/findings/nhqrdr/nhqdr16/index.html. Accessed June 19, 2018.

- Heins JK, Heins A, Grammas M, Costello M, Huang K, Mishra S. Disparities in analgesia and opioid prescribing practices for patients with musculoskeletal pain in the emergency department. J Emerg Nurs. 2006;32(3):219-224. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jen.2006.01.010

- Nelson A. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. J Natl Med Assoc. 2002;94(8):666-668.

- Teal CR, Gill AC, Green AR, Crandall S. Helping medical learners recognise and manage unconscious bias toward certain patient groups. Med Educ. 2012;46(1):80-88. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2923.2011.04101.x

- Greenwald AG, McGhee DE, Schwartz JL. Measuring individual differences in implicit cognition: the implicit association test. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1998;74(6):1464-1480. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.74.6.1464

- van Ryn M, Hardeman R, Phelan SM, et al. Medical school experiences associated with change in implicit racial bias among 3547 students: A medical school CHANGES study. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(12)1748-1756. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-015-3447-7

- Chapman EN, Kaatz A, Carnes M. Physicians and implicit bias: how doctors may unwittingly perpetuate health care disparities. J Gen Intern Med. 2013;28(11):1504-1510. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-013-2441-1

- Sukhera J, Milne A, Teunissen PW, Lingard L, Watling C. The actual versus idealized self: exploring responses to feedback about implicit bias in health professionals. Acad Med. 2018;93(4):623-629. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002006

- Lebrecht S, Pierce LJ, Tarr MJ, Tanaka JW. Perceptual other-race training reduces implicit racial bias. PLoS One. 2009;4(1):e4215. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0004215

- Galinsky AD, Moskowitz GB. Perspective-taking: decreasing stereotype expression, stereotype accessibility, and in-group favoritism. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2000;78(4):708-724. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.78.4.708

- Hobbs J. White privilege in health care: following recognition with action. Ann Fam Med. 2018;15(3)197-198. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2243.

- Acosta D, Ackerman-Barger K. Breaking the silence: time to talk about race and racism. Acad Med. 2017;92(3):285-288. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001416

- Nelson SC, Prasad S, Hackman HW. Training providers on issues of race and racism improve health care equity. Pediatr Blood Cancer. 2015;62(5):915-917. https://doi.org/10.1002/pbc.25448

- Hofmann W, Gawronski B, Gschwendner T, Le H, Schmitt M. A meta-analysis on the correlation between the implicit association test and explicit self-report measures. Pers Soc Psychol Bull. 2005;31(10):1369-1385. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167205275613

There are no comments for this article.