Background and Objectives: Health advocacy has been declared an essential physician skill in numerous professional physician charters. However, there is limited literature on whether, and how, family medicine residencies teach this skill. Our aim was to determine the prevalence of a formal mandatory advocacy curriculum among US family medicine residencies, barriers to implementation, and what characteristics might predict its presence.

Methods: Questions about residency advocacy curricula, residency characteristics, and program director (PD) attitudes toward family medicine and advocacy were included in the 2017 Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine residency PDs. We used univariate and bivariate statistics to describe residency characteristics, PD attitudes, the presence of a formal advocacy curriculum, and the relationship between these.

Results: Of 478 PDs, 261 (54.6%) responded to the survey and 236/261 (90.4%) completed the full advocacy module. Just over one-third (37.7%, (89/236)) of residencies reported the presence of a mandatory formal advocacy curriculum, of which 86.7% (78/89) focused on community advocacy. The most common barrier was curricular flexibility. Having an advocacy curriculum was positively associated with faculty experience and optimistic PD attitudes toward advocacy.

Conclusions: In a national survey of family medicine PDs, only one-third of responding PDs reported a mandatory advocacy curriculum, most focusing on community advocacy. The largest barrier to implementation was curricular flexibility. More research is needed to explore the best strategies to implement these types of curricula and the long-term impacts of formal training.

Advocacy is an essential domain of professionalism as defined by numerous physician standards.1-3 The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Common Program Requirements for all specialties include advocating for patients, and other specialties, including family medicine further emphasize health advocacy in their milestones for systems-based practice and professionalism.2,4 However, there is no defined national health advocacy framework within graduate medical education in the United States. Furthermore, despite consensus of the importance of advocacy and policy training among regulatory bodies, published literature discussing the successful implementation of curricula remains scant.5 The number of graduate medical education programs that address advocacy training is unknown, as are the barriers residencies face in establishing these curricula.

Health advocacy is commonly defined as

purposeful actions to address determinants of health which negatively impact individuals or communities by either informing those who can enact change or by initiating, mobilizing, and organizing activities to make change happen, with or on behalf of the individuals or communities with whom health professionals work.6

It is one piece of a toolkit that physicians can use to improve patient health.7 While there is limited data describing the effect of advocacy on individual health outcomes, physician advocacy has helped expose the harms of the Tuskegee syphilis study,8 increased understanding and testing for sickle cell disease,9 and uncovered lead in the water of Flint, Michigan.10 In the current environment of rapid health care changes and calls for increased social accountability from medical education systems,11-14 we must focus on how to teach advocacy.7,12,14,15

Previous studies indicate that for physicians to advocate efficiently, quality structured advocacy training is important to support and develop skills.12,14 Although developing a physician advocate requires longitudinal training and practice,16 emphasizing the need for early career engagement, this role has also been identified as one of the most difficult to teach and to evaluate.17,18 We aimed to determine the prevalence of a formal mandatory advocacy curriculum among family medicine residencies and program directors’ perceived barriers to instituting such curricula. Secondarily, we aimed to determine which, if any, residency and program director (PD) characteristics might predict the presence of an advocacy curriculum. We hypothesized that few residency programs would have a mandatory advocacy curriculum, and that family medicine PD characteristics and attitudes have a significant role to play in the presence of an advocacy curriculum.

Study Design and Data Collection

We conducted a cross-sectional study of family medicine residencies. Advocacy-related survey questions were included in the 2017 Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey for program directors (PDs). The CERA committee tested questions prior to inclusion. The development of the omnibus survey and its methodology have been described elsewhere.19

An invitation to participate in the online CERA survey was emailed to all 499 ACGME-accredited US family medicine residency PDs in January 2017. Five subsequent reminders were emailed through March 2017. Of the 499 PDs identified, 10 PDs had previously opted out of CERA surveys and 11 emails could not be delivered. The final sample size was 478.

The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Measures

The advocacy-specific module consisted of 13 questions (See Appendix at https://journals.stfm.org/media/3012/appendix1-coutinho-fammed2020.pdf), asking about the presence of a mandatory formal advocacy curriculum, barriers and motivations to implementation, residency characteristics, and overall PD attitudes toward family medicine and advocacy. Advocacy was defined for participantsusing the definition in the introduction with an addendum stating, “This includes work at the community, state, or federal level, including establishing strong, longitudinal community partnerships, influencing health policy, or creating new programs as examples.” The addendum was included to further describe the context for which physician advocacy is commonly performed. All questions allowed one response per question, except for that identifying community, state, and/or federal level involvement.

Analysis

Univariate statistics described residency and PD characteristics as well as the presence of a formal advocacy curriculum and its type and duration. Bivariate statistics explained relationships between the presence of an advocacy curriculum with the aforementioned variables. χ2 tests assessed significance. A P value of <.05 defined statistical significance. We analyzed data with STATA 13.1 (College Station, TX).

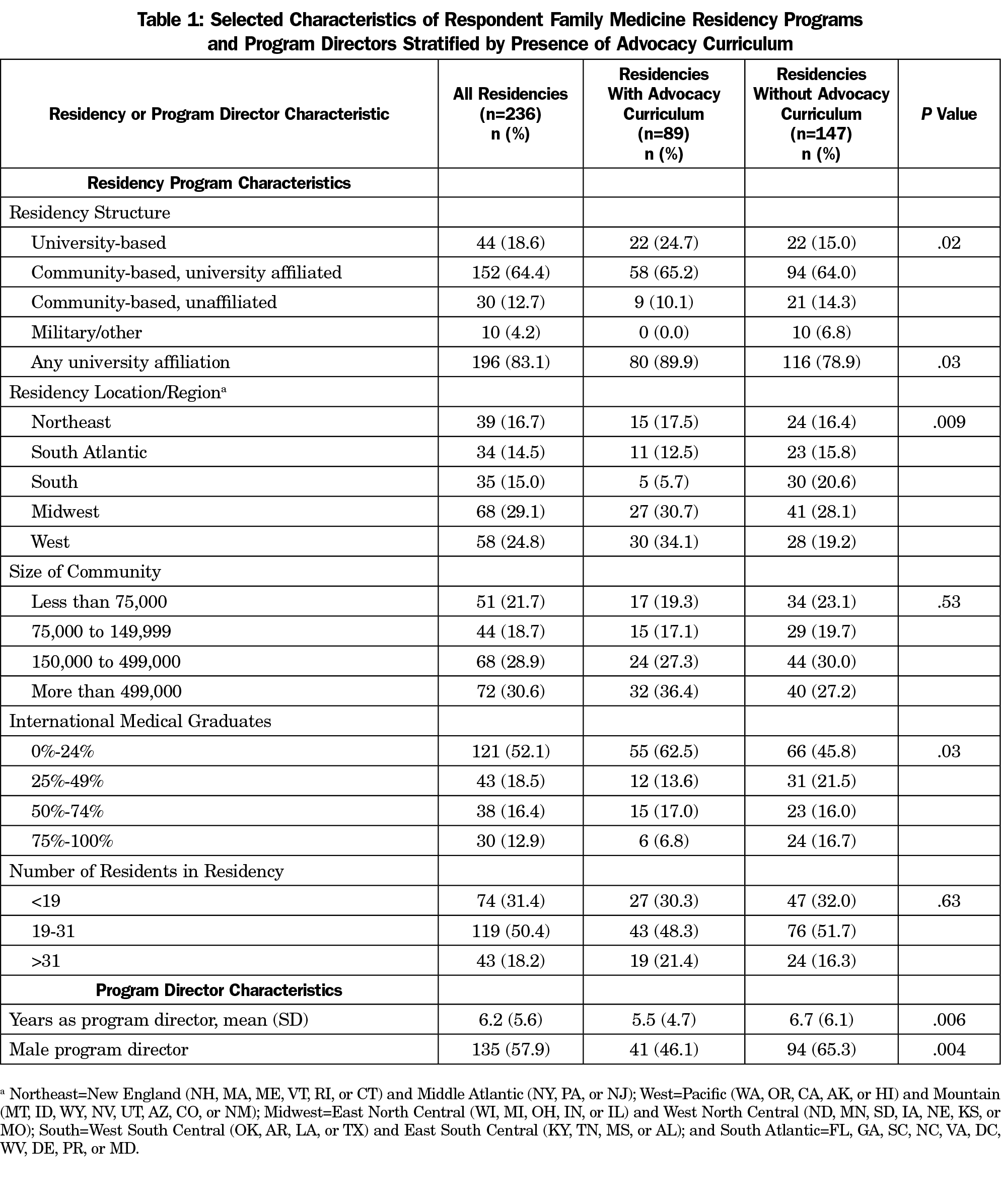

Residency Characteristics

The response rate for the CERA survey was 54.6% (261/478), of which 90.4% (236/261) completed all questions of the advocacy module, creating an overall response rate of 49.4% (236/478). PD respondents (Table 1) were reflective of the expected structure and location of ACGME-accredited residencies (not presented). The majority of residencies (64.4%, 152/236) were community-based/university-affiliated residencies.

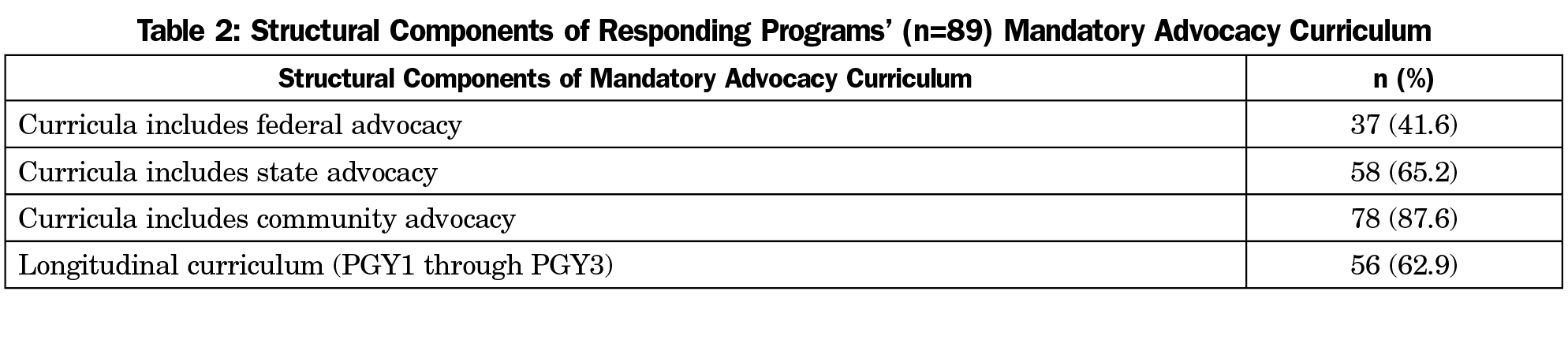

Advocacy Curricula Characteristics

Of the 236 PDs who answered all questions of the advocacy module, 89 (37.7%) reported a formal, mandatory advocacy curriculum (Table 2). Among residencies with advocacy curricula, fewer had federal advocacy components (41.6%, 37/89) than compared to state (65.2%, 58/89) or community (87.6%, 78/89) components. Curricula most often took place longitudinally over 2 years or more (83.1%, 74/89) with the majority over 3 years (62.9%, 56/89). Of residencies without a formal advocacy curriculum, 87.8% (129/147) were able to refer interested residents to optional elective opportunities.

Health disparities, health equity, social determinants of health, and creating and maintaining community partnerships were the most important topics for curricula. Other topics were creating and maintaining community partnerships, change management, health policy, health economics, and community skills (in order of importance to PDs). There were no statistically significant differences in the rankings of importance of these education topics between residencies with and without an advocacy curriculum (data not shown).

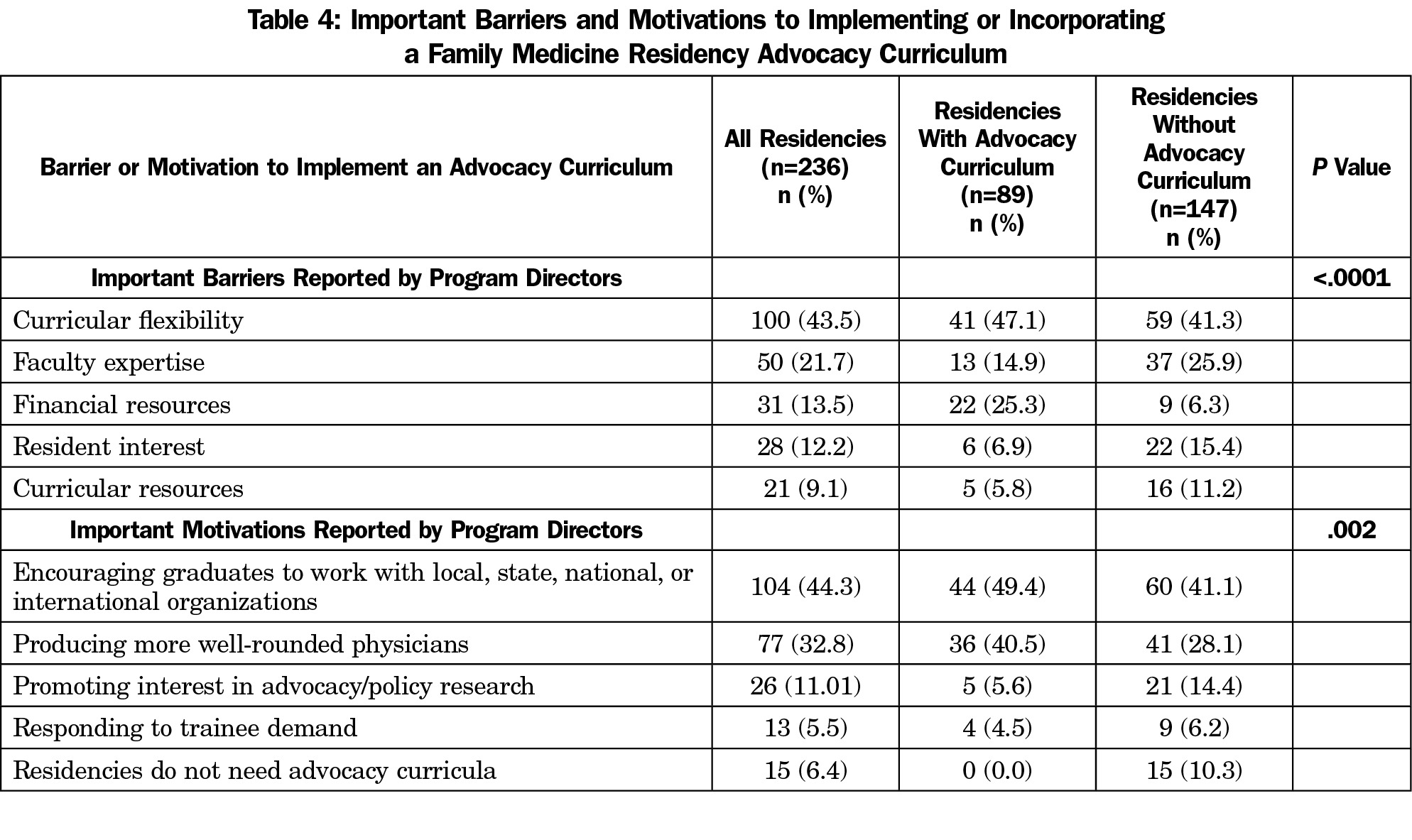

Barriers and Motivations

The most significant barrier cited was curricular flexibility (43.5%, 100/236; Table 4) followed by faculty expertise (21.7%, 50/236). Respondents without an advocacy curriculum were more likely to cite the need for more faculty expertise and curricular resources, compared to residencies with an already-established curriculum, who cited financial restrictions (P<.001). Residencies were most motivated to include advocacy curricula to encourage graduates to work with local, state, national or international officials or organizations (44.3%, 104/236) and produce more well-rounded physicians (32.8%, 77/236).

Mandatory Incorporated Advocacy Curricula Associations

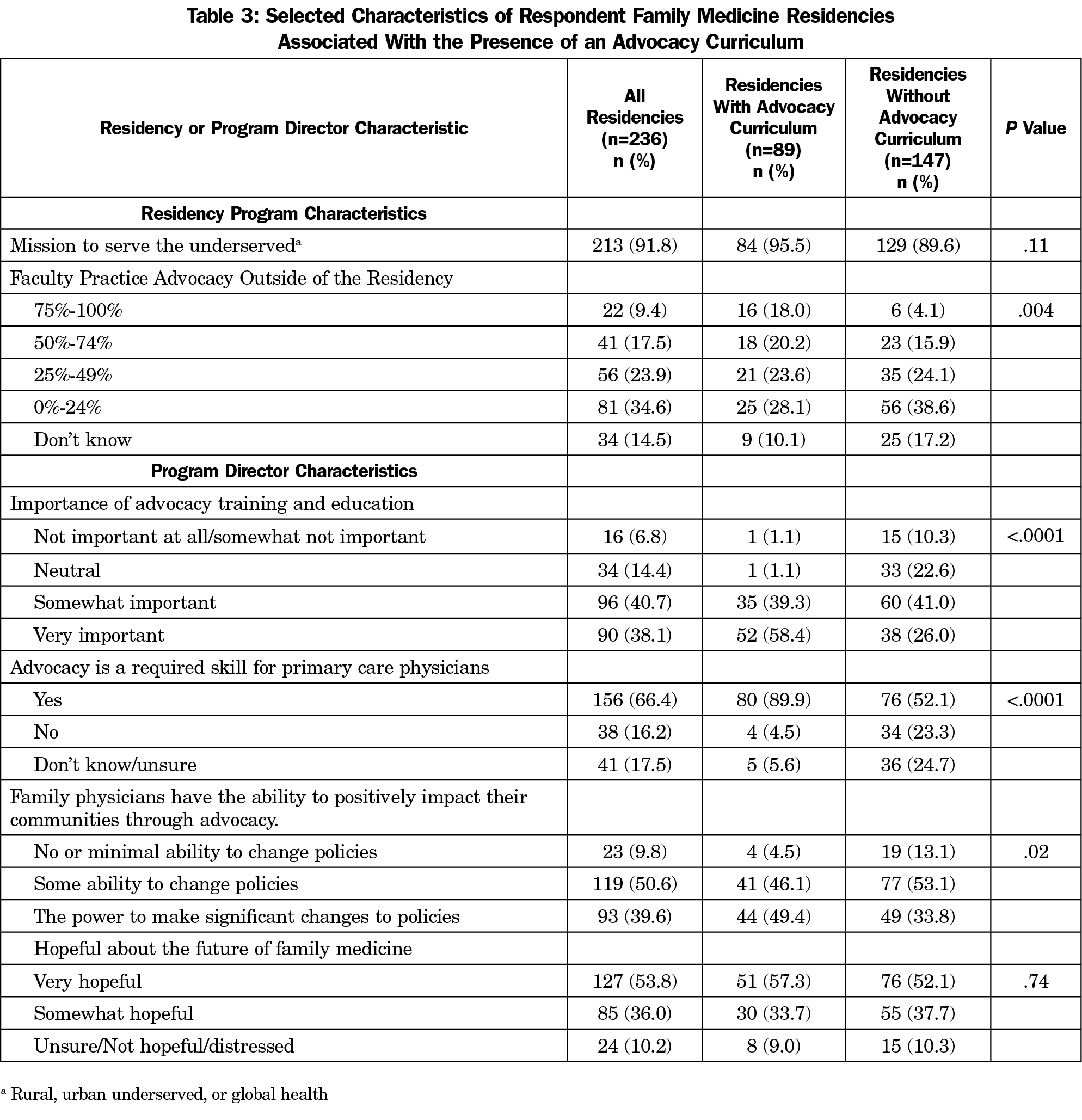

Having a university affiliation, regional geography, and a smaller percentage of international medical graduates were positively associated with having an advocacy curriculum (P<.05; Table 1). Size of community and total number of residents had no statistically significant correlation with the presence of curricula. Residencies with a female PD, faculty with experience, or a newer PD were more likely to have an advocacy curriculum (P<.005; Table 1 and Table 3).

Program Director Attitudes

The majority of PDs (66.4%) believed that advocacy is a required skill for a primary care physician (Table 3). Residencies were more likely to have an advocacy curriculum if the PD had favorable advocacy attitudes: rating the importance of advocacy training and education higher (P<.001), demonstrating belief that advocacy was a required skill for primary care physicians (P<.001), or advocacy could have a positive effect (P<.05). Mission to serve the underserved and PD hopefulness about the future of family medicine were not associated with an advocacy curriculum.

This national survey of family medicine PDs shows that the majority of PDs believe advocacy is an important skill for a primary care physician, yet just over one-third of respondents have a formal, mandatory advocacy curriculum. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper to describe the prevalence of an advocacy curriculum within a graduate medical education specialty. Although we expected residencies with an underserved mission would be more likely to have advocacy curricula, this was not the case. The uncertainty of the future of health care has driven an increase in physicians acting as advocates, many perhaps for the first time.20 Structured, quality advocacy education will be important to prepare physicians to engage with communities and policy makers.

While the majority of PDs agreed advocacy was an important skill for physicians, this did not consistently correlate with presence of a curriculum. Our findings echo previous surveys in which the majority of physicians indicated advocacy was important, but few actually practiced it.18,21 This lack of engagement is likely related to numerous factors, including lack of understanding of the political process and how to become involved, the underemphasis compared to other components of clinical medicine or research, and time management habits.22 If professional organizations and credentialing bodies believe advocacy is a component of professional physician practice, it is important to create structured, formalized time within residency for the training of these skills.

The most commonly cited barrier of curricular flexibility is similar to previous studies.18,23 While general mentions of advocacy are included in ACGME Common Program Requirements and Family Medicine Milestones, there are no defined competencies or specific descriptors of what advocacy education should entail.24 For programs without faculty experience, the breadth of material involved in policy and advocacy knowledge and skills may be overwhelming beyond just curricular flexibility.25 Therefore, it is unsurprising that university-affiliated programs were more likely to have a formal curriculum and that community-based unaffiliated programs were underrepresented as respondents compared to their prevalence in family medicine residency programs.

Among the small number of curricular outlines published, many have difficulty in transferability due to availability of resources.25-28 Guidance from the ACGME through creating competencies and detailed program requirements or helping with educational programming development, as they have done with other nonclinical topics,29 may be helpful. An online and shared curriculum may also be helpful to guiding residencies who feel inadequately prepared.

The majority of reported advocacy curricula focused on community-based advocacy without expansion into state or federal domains. Engagement in each level of advocacy has the opportunity to teach differing skills. Community-based advocacy may highlight creating partnerships with local organizations while state and federal advocacy may emphasize interacting with legislators and understanding the broader political and financial impacts on health care delivery.

Our study indicates a higher rate of faculty engaged with advocacy activities than previously described.23,24 Earlier studies were conducted across multiple specialties whereas ours examined only family medicine residencies. Most faculty indicated advocacy involvement at the federal level, whereas residencies focused on community engagement. Residencies may not be leveraging the skills of their faculty given curricular flexibility restraints. Qualitative studies of physician advocates indicate that exposure was a crucial experience to development, emphasizing the need for experienced faculty as mentors throughout medical education.12,16

Study limitations include an overall response rate of 49%, inherent to response bias, with questions subject to self-report bias and socially desirable answers. Although our module did have a 90% response rate, it is likely that those with an advocacy curriculum preferentially completed the survey, and our results may overestimate the actual prevalence of curricula. Although advocacy was defined at the start of the survey, curriculum was not and may have been interpreted variably; therefore, counted curricula could range from a 1-hour lecture to building community partnerships with local organizations. The results may not be generalizable to other residency specialties. We did not adjust P values for multiple associations, and acknowledge that some of the associations may be spurious.

Areas for further research include comparisons across medical specialties, the assessment of available curricula to determine key content and best practices, and the impact of curricula on physician behavior and health outcomes. Additional research could also explore the important role of PDs’ age and gender and why only some respondents, irrespective of the presence of a residency curriculum, believed that physicians are able to be agents of change.

Despite emphasis on advocacy as a component of physician professionalism and inclusion in ACGME requirements and milestones, in a national survey of family medicine PDs, only one-third of residencies had a mandatory advocacy curriculum, most focusing on community advocacy. The most-cited barrier was curricular flexibility; thus, regulatory body support in development of competencies and/or curricula may be helpful. Advocacy exposure throughout medical education may influence physicians’ future abilities to successfully engage in local, state, or national issues. Using organizational bodies to help family medicine residencies meet existing milestones may improve advocacy education dissemination.

Acknowledgments

Funding/Support Disclosures: Dr Moreno received support from a National Institute on Aging (NIA; K23 AG042961-01) Paul B. Beeson Career Development Award, the American Federation for Aging Research, and from the UCLA Resource Centers for Minority Aging Research, Center for Health Improvement of Minority Elderly under National Institutes of Health (NIH)/NIA grant P30-AG021684. The content of this article does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIA or the NIH.

Previous Presentations: Coutinho A, Nguyen B, Moreno G, Kelly C, Gits A, Lin K, Crichlow R. Characteristics Associated with Advocacy Training in Family Medicine Residency Programs. Oral presentation at 45th Annual Meeting of the North American Primary Care Research Group. Montreal, Quebec, Canada. November 18, 2017.

References

- ABIM Foundation. American Board of Internal MedicineACP-ASIM Foundation. American College of Physicians-American Society of Internal MedicineEuropean Federation of Internal Medicine. Medical professionalism in the new millennium: a physician charter. Ann Intern Med. 2002;136(3):243-246. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-136-3-200202050-00012

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements. http://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed June 12, 2017.

- American Medical Association. Declaration of professional responsibility: medicine’s social contract with humanity. Mo Med. 2002;99(5):195.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; American Board of Family Medicine. The Family Medicine Milestone Project. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PDFs/Milestones/FamilyMedicineMilestones.pdf. Accessed May 8, 2017.

- Earnest MA, Wong SL, Federico SG. Perspective: physician advocacy: what is it and how do we do it? Acad Med. 2010;85(1):63-67. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181c40d40

- Oandasan IF. Health advocacy: bringing clarity to educators through the voices of physician health advocates. Acad Med. 2005;80(10)(suppl):S38-S41. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200510001-00013

- Croft D, Jay SJ, Meslin EM, Gaffney MM, Odell JD. Perspective: is it time for advocacy training in medical education? Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1165-1170. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826232bc

- Seelye K. Bill Jenkins, Who Tried to Halt Tuskegee Syphilis Study, Dies at 73. The New York Times. February 25, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/25/obituaries/bill-jenkins-dead.html. Accessed January 8, 2020.

- Roberts S. Dr. Doris Wethers, 91, on Front Lines Against Sickle Cell, Dies. The New York Times. February 7, 2019. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/07/obituaries/dr-doris-wethers-on-front-lines-against-sickle-cell-dies-at-91.html. Accessed January 8, 2020.

- Hanna-Attisha M. Opinon: How a Pediatrician Became a Detective. The New York Times. June 9, 2018. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/06/09/opinion/sunday/flint-water-pediatrician-detective.html. Accessed January 8, 2020.

- Mullan F, Chen C, Petterson S, Kolsky G, Spagnola M. The social mission of medical education: ranking the schools. Ann Intern Med. 2010;152(12):804-811. https://doi.org/10.7326/0003-4819-152-12-201006150-00009

- Dharamsi S, Ho A, Spadafora SM, Woollard R. The physician as health advocate: translating the quest for social responsibility into medical education and practice. Acad Med. 2011;86(9):1108-1113. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e318226b43b

- Saultz J. Family Medicine Student Interest. Fam Med. 2015;47(10):761-762.

- Sklar DP. Why Effective Health Advocacy Is So Important Today. Acad Med. 2016;91(10):1325-1328. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001338

- Clancy TE, Fiks AG, Gelfand JM, et al. A call for health policy education in the medical school curriculum. JAMA. 1995;274(13):1084-1085. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.274.13.1084

- Oandasan IF, Barker KK. Educating for advocacy: exploring the source and substance of community-responsive physicians. Acad Med. 2003;78(10)(suppl):S16-S19. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200310001-00006

- Verma S, Flynn L, Seguin R. Faculty’s and residents’ perceptions of teaching and evaluating the role of health advocate: a study at one Canadian university. Acad Med. 2005;80(1):103-108. https://doi.org/10.1097/00001888-200501000-00024

- Stafford S, Sedlak T, Fok MC, Wong RY. Evaluation of resident attitudes and self-reported competencies in health advocacy. BMC Med Educ. 2010;10(1):82. https://doi.org/10.1186/1472-6920-10-82

- Mainous AG III, Seehusen D, Shokar N. CAFM Educational Research Alliance (CERA) 2011 Residency Director survey: background, methods, and respondent characteristics. Fam Med. 2012;44(10):691-693.

- Griffiths EP. Effective legislative advocacy – lessons from successful medical trainee campaigns. N Engl J Med. 2017;376(25):2409-2411. https://doi.org/10.1056/NEJMp1704120

- Gruen RL, Campbell EG, Blumenthal D. Public roles of US physicians: community participation, political involvement, and collective advocacy. JAMA. 2006;296(20):2467-2475. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.296.20.2467

- Nerlinger AL, Shah AN, Beck AF, et al. The Advocacy Portfolio: A Standardized Tool for Documenting Physician Advocacy. Acad Med. 2018;93(6):860-868. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000002122

- Cole McGrew M, Wayne S, Solan B, Snyder T, Ferguson C, Kalishman S. Health policy and advocacy for New Mexico medical students in the family medicine clerkship. Fam Med. 2015;47(10):799-802.

- Jacobs DB, Greene M, Bindman AB. It’s academic: public policy activities among faculty members in a department of medicine. Acad Med. 2013;88(10):1460-1463. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182a37329

- Basu G, Pels RJ, Stark RL, Jain P, Bor DH, McCormick D. Training Internal Medicine Residents in Social Medicine and Research-Based Health Advocacy: A Novel, In-Depth Curriculum. Acad Med. 2017;92(4):515-520. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000001580

- Bachofer S, Velarde L, Clithero A. Laying the foundation: a residency curriculum that supports informed advocacy by family physicians. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(4)(suppl 3):S312-S313. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.014

- Long T, Chaiyachati KH, Khan A, Siddharthan T, Meyer E, Brienza R. Expanding Health Policy and Advocacy Education for Graduate Trainees. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(3):547-550. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-13-00363.1

- Chamberlain LJ, Wu S, Lewis G, et al; California Community Pediatrics and Legislative Advocacy Training Collaborative. A multi-institutional medical educational collaborative: advocacy training in California pediatric residency programs. Acad Med. 2013;88(3):314-321. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182806291

- Jardine D, Correa R, Schultz H, et al. The Need for a Leadership Curriculum for Residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2015;7(2):307-309. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-07-02-31

There are no comments for this article.