Background and Objectives: The purpose of this study was to examine the impact of racism experienced by physicians of color in the workplace.

Methods: We utilized a mixed-methods, cross-sectional, survey design. Seventy-one participants provided qualitative responses describing instances of racism from patients, colleagues, and their institutions. These responses were then coded in order to identify key domains and categories. Participants also completed quantitative measures of their professional quality of life and the incidence of microaggressions experienced while at work.

Results: We found that physicians of color were routinely exposed to instances of racism and discrimination while at work. Twenty-three percent of participants reported that a patient had directly refused their care specifically due to their race. Microaggressions experienced at work and symptoms of secondary traumatic stress were significantly correlated. The qualitative data revealed that a majority of participants experienced significant racism from their patients, colleagues, and institutions. Their ideas for improving diversity and inclusion in the workplace included providing spaces to openly discuss diversity work, constructing institutional policies that promote diversity, and creating intentional hiring practices that emphasize a more diverse workforce.

Conclusions: Physicians of color are likely to experience significant racism while providing health care in their workplace settings, and they are likely to feel unsupported by their institutions when these experiences occur. Institutions seeking a more equitable workplace environment should intentionally include diversity and inclusion as part of their effort.

In 2003, the Institute of Medicine released their comprehensive report on racism in medicine, which documented extensive racial disparities across a multitude of health outcomes.1 Since then, there has been accumulating evidence that racism, discrimination, implicit bias, and structural inequalities have substantially impacted health care delivery and outcomes.2-4 Although there is a growing body of evidence documenting the harmful effects of racism on patient care, comparatively much less is known about how racism and discrimination affect physicians of color.5,6 The long-term impact of such occupational stressors such as racism and discrimination remains unknown, especially as it relates to job satisfaction and burnout.

A recent commentary on this issue concluded that it is critical that researchers begin to study how discrimination affects physicians of color.7 Thus, the primary purpose of this study was to survey physicians of color about their experiences regarding institutional racism, racism from colleagues, and racism from patients using a qualitative approach. A secondary purpose of this study was to examine the impact of workplace microaggressions on professional quality of life. Using a quantitative approach, we hypothesized that a greater incidence of microaggressions experienced at work would be correlated with higher levels of burnout indicators.

This study consisted of a cross-sectional, mixed-methods, survey design and was approved by our institutional review board. We sent a survey to physicians of color through the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine’s (STFM) Group on Minority and Multicultural Health and through the behavioral scientists’ network. For the purposes of this study, “physicians of color” was defined as any individual who (1) held a physician’s license to practice medicine, and (2) identified as either: American Indian or Alaska Native, Asian, black or African American, Hispanic or Latino, Native Hawaiian or other Pacific Islander, or multiracial.

Participants completed the Racial and Ethnic Microaggressions Scale’s subscale on workplace microaggressions, in which microaggressions were defined as “subtle statements and behaviors that unconsciously communicate denigrating messages to people of color.”8 Participants also completed the Professional Quality of Life Scale (which measures compassion satisfaction, burnout, and secondary traumatic stress),9 and a demographics questionnaire. They also answered open-ended qualitative items in which they were asked to describe an instance of institutional racism, an instance of racism from a colleague, and an instance of racism from patients. Participants also reported how organizations could better support physicians of color experiencing racism. We analyzed the qualitative items using a version of the consensual qualitative research method modified for brief responses.10 We analyzed the bivariate and multivariate data using correlation and ANOVA statistical tests. Bonferroni corrections were used for multiple comparisons.

Of the 71 survey participants, 72% identified as female, 23.3% as male, and 1.4% as nonbinary. The mean age was 35 years (SD=8.52), and the mean number of years practicing medicine was 7.22 (SD=7.55). Regarding race/ethnicity, 34.2% identified as black, 34.2% as Asian, 24.7% as Latinx/Hispanic, and 1.4% as American Indian or Alaskan Native. Regarding medical specialty, 87.7% identified as family physicians. Nearly 33% reported that English was their second language.

We found that 23.3% of participants reported that a patient had refused their care specifically due to their race/ethnicity. Another 21.9% stated they were unsure if a patient refusal for care was due to their race/ethnicity, but that it had occurred. Microaggressions were not significantly correlated with compassion fatigue or burnout, but they were positively correlated with a measure of secondary traumatic stress (r=.26, P=.03). racism from patients (SD=1.94), and the mean was 4.24 (SD=12.31) instances of racism from colleagues/medical staff. Participants who reported English as their second language reported significantly more instances of racism from patients (M=2.32, SD=2.71); t=-2.16, P=.04), than those who spoke English as a first language (M=.89, SD=1.31). There were no significant differences between males and females on these outcome measures.

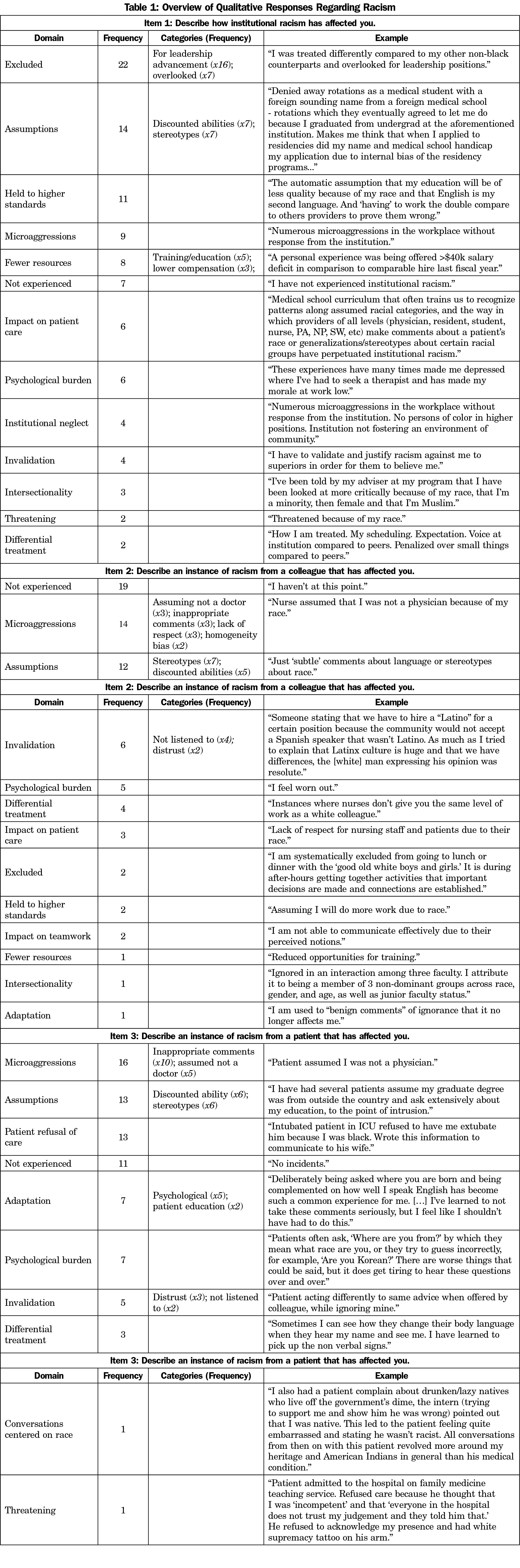

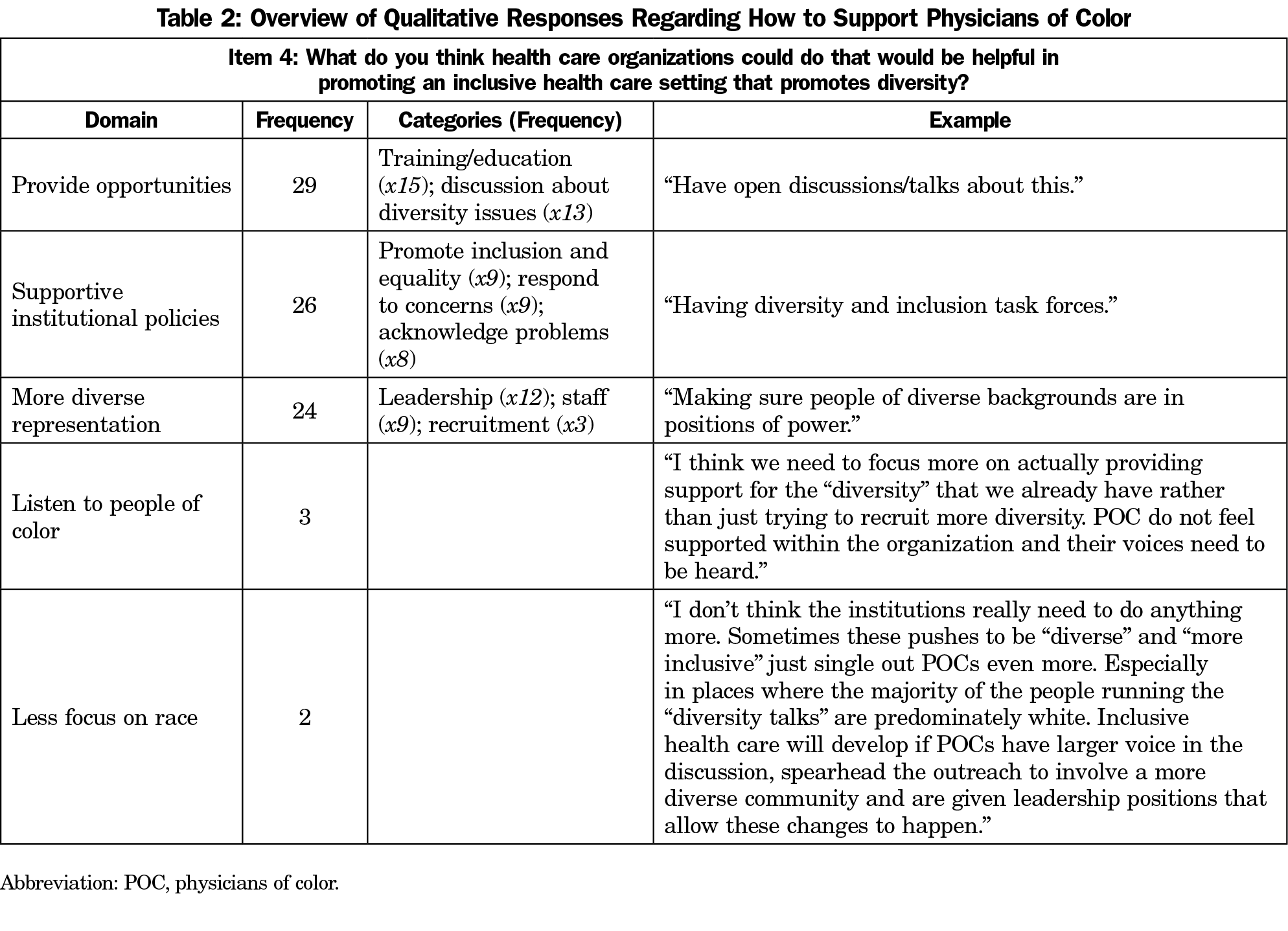

For each qualitative item, several domains and categories were identified. Responses to instances of racism are summarized in Table 1. Participant suggestions for more inclusive health care settings are summarized in Table 2.

We found that a majority of the physicians surveyed reported instances of racism and discrimination from patients, colleagues, and the institutional climate. Examples included assumptions that participants were actually not physicians, inappropriate comments about their race, and structural biases that led to substantially fewer advancement opportunities. These qualitative responses were substantiated by the quantitative data, in which we found that microaggressions experienced at work were significantly correlated with secondary traumatic stress, an important element of professional quality of life.9 Because these data are correlational, we cannot infer causality, but it is clear that participants experienced a significant emotional labor burden as a result of these instances.11 Many participants cited that these instances impacted their mental health and/or their sense of well-being. Notably, participants reported that they were more likely to experience racism from their colleagues in comparison to their patients. The finding that physicians who reported English as a second language experienced more instances of racism from patients might suggest that it is more socially acceptable to discriminate based on language than race. Finally, participants also recommended that institutions provide more opportunities to openly discuss diversity work, create institutional policies that are supportive of diversity and inclusion, and hire a more diverse workforce.

These findings are important to the field of family medicine because although there has been increasing focus on the impact of racism on patient outcomes,1-4 there has been relatively little research on the effects of racism on health care providers. Our results indicate that physicians of color often face racism and discrimination in the workplace, and this represents an occupational hazard that has the potential to negatively impact their career advancement and sense of well-being. One limitation to this study is the cross-sectional design, in which we did not follow physicians’ experience of racism and burnout longitudinally. However, even based on these limited data, it is clear that physicians of color do experience significant instances of racism at work, and that institutions can and should do more to provide an inclusive environment. Another limitation is that we were not able to fully explore the effects of intersectionality (eg, belonging to other marginalized and oppressed groups) and their impact on outcomes. Future research should examine the impact of specific institutional initiatives on the prevalence of instances of racism and discrimination experienced while at work. Until these data are systematically tracked, institutions will not be able to measure progress toward a more inclusive environment.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: This study received a project funding grant from the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine.

References

- Smedley BD, Stith AY, Nelson AR. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2003.

- Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS One. 2015;10(9):e0138511. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0138511

- Paradies Y. A systematic review of empirical research on self-reported racism and health. Int J Epidemiol. 2006;35(4):888-901. https://doi.org/10.1093/ije/dyl056

- Blair IV, Steiner JF, Fairclough DL, et al. Clinicians’ implicit ethnic/racial bias and perceptions of care among Black and Latino patients. Ann Fam Med. 2013;11(1):43-52. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1442

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Diversity in the physician workforce: facts and figures 2014. https://www.aamcdiversityfactsandfigures.org/section-ii-current-status-of-us-physician-workforce/index.html. Accessed October 16, 2019.

- Pololi L, Cooper LA, Carr P. Race, disadvantage and faculty experiences in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2010;25(12):1363-1369. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11606-010-1478-7

- Rasmussen BM, Garran AM. In the line of duty: racism in health care. Soc Work. 2016;61(2):175-177. https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/sww006

- Nadal KL. The Racial and Ethnic Microaggressions Scale (REMS): construction, reliability, and validity. J Couns Psychol. 2011;58(4):470-480. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0025193

- ProQOL.org. Professional Quality of Life Measure. www.proqol.org. Accessed November 27, 2019.

- Spangler PT, Liu J, Hill CE. Consensual qualitative research for simple qualitative data: an introduction to CQR-M. In: Hill CE, ed. Consensual Qualitative Research: A Practical Resource for Investigating Social Science Phenomena. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association; 2012.

- Cottingham MD, Johnson AH, Erickson RJ. “I can never be too comfortable”: race, gender, and emotion at the hospital bedside. Qual Health Res. 2018;28(1):145-158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732317737980

There are no comments for this article.