Decades of research consistently shows that health outcomes improve with an increasing supply of primary care physicians.1-8 In the United States, primary care is commonly associated with the specialties of general internal medicine, general pediatrics, and family medicine.9 Sometimes, obstetrics and gynecology and geriatrics are included as primary care disciplines, however, family medicine is the only one of these specialties that provides comprehensive care for all patients regardless of age or gender. Among physician specialties, the distribution of family physicians most closely mirrors the distribution of the US population.10

The United States is experiencing current and projected primary care shortages related to both physician workforce composition and geographic distribution of practicing clinicians.11,12 Further, because the population is aging and the prevalence of chronic illness among adults has increased, the shortage of primary care providers for adults is particularly important.12 Over the past 4 decades, fewer than half of internal medicine physicians remained generalists and now nearly 90% choose subspecialty practices.13 While the supply of generalist pediatricians is projected to be stable at the national level,14 there are projected regional pediatric workforce deficits.15 Because of these factors, increasing the proportion of students who choose family medicine may be the most efficient way to optimize the US primary care physician workforce.

Most students choosing family medicine careers practice primary care,16 however, many medical students who intend to practice primary care choose other specialties, particularly internal medicine, internal medicine-pediatrics, and pediatrics, and are thus less likely to ultimately practice primary care.

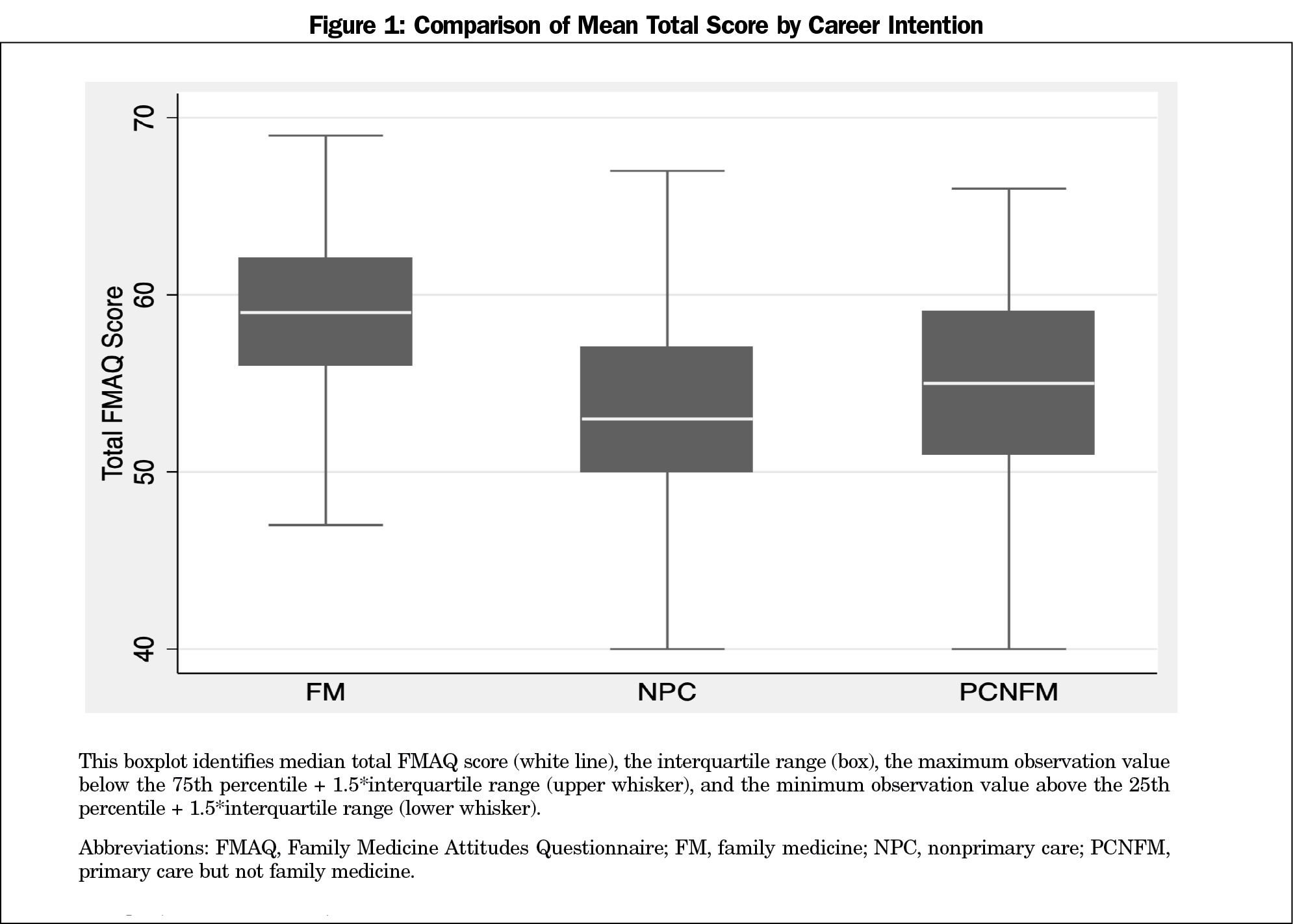

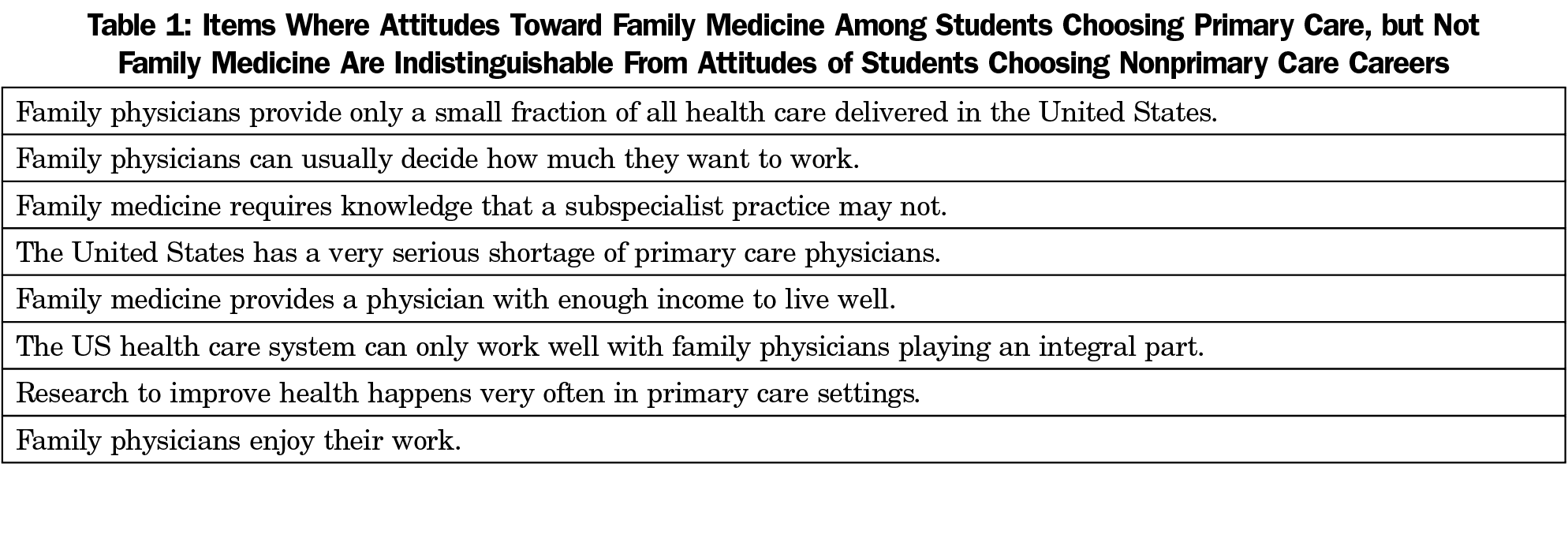

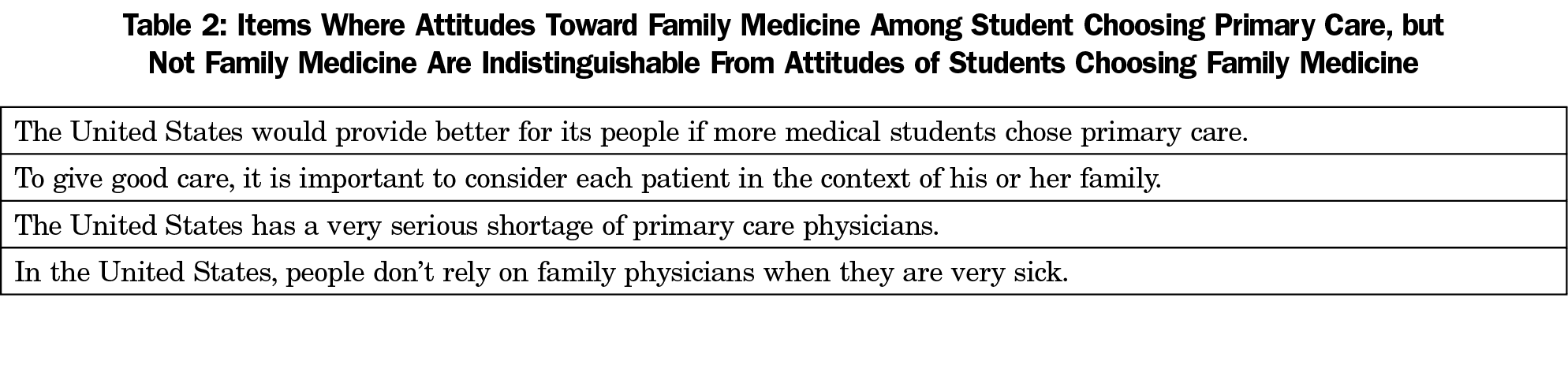

Little is known about how students choose between primary care specialties, but one study suggests that students make decisions based on their preferred patient population and the specialty’s approach toward patient care.17 Students interested in primary care may share characteristics that differ from other students, such as lower family socioeconomic status, origination from rural or other underserved areas, nontraditional routes to medical school, or identification as members of racial minority groups18; these personal characteristics could also contribute to similar attitudes toward primary care for such students. At the same time, student specialty preference for family medicine varies at medical school matriculation, and may also be influenced by the medical school curriculum, family medicine interest group participation, and other institutional characteristics.19 We sought to understand the attitudes toward family medicine of fourth-year medical students who intend to practice primary care, but not family medicine. Specifically, we aimed to identify whether these students’ attitudes toward family medicine closely align with students intending family medicine (FM), or more closely align with students planning a nonprimary care practice. We hypothesized that because these students intend to practice primary care, they would have a similarly positive attitude toward primary care as the students planning FM careers, and thus a positive attitude toward family medicine as well.

There are no comments for this article.