Background and Objectives: Residents need to learn about practice management, including how to improve the quality of their patient care utilizing practice data. However, little is known about the effectiveness of providing practice data to residents. This study examined the effectiveness of utilizing resident practice management reports.

Methods: We provided residents quarterly practice management reports with individual resident data on coding compliance (determined by manual chart review by a certified coder), clinical productivity (number of clinic sessions, visits per session, relative value units [RVUs] per visit, and RVUs per session), and patient quality outcomes (rates of diabetes mellitus control, diabetic nephropathy screening/management, hypertension control, influenza immunization, pneumococcal immunization, and colorectal cancer screening). We compared all data to national metrics. Quality outcome data was also provided by clinical team and with comparison to nonresidency departmental clinics. We surveyed residents before and after receiving these practice management reports to determine how they felt it prepared them for future practice (on a 9-point Likert scale).

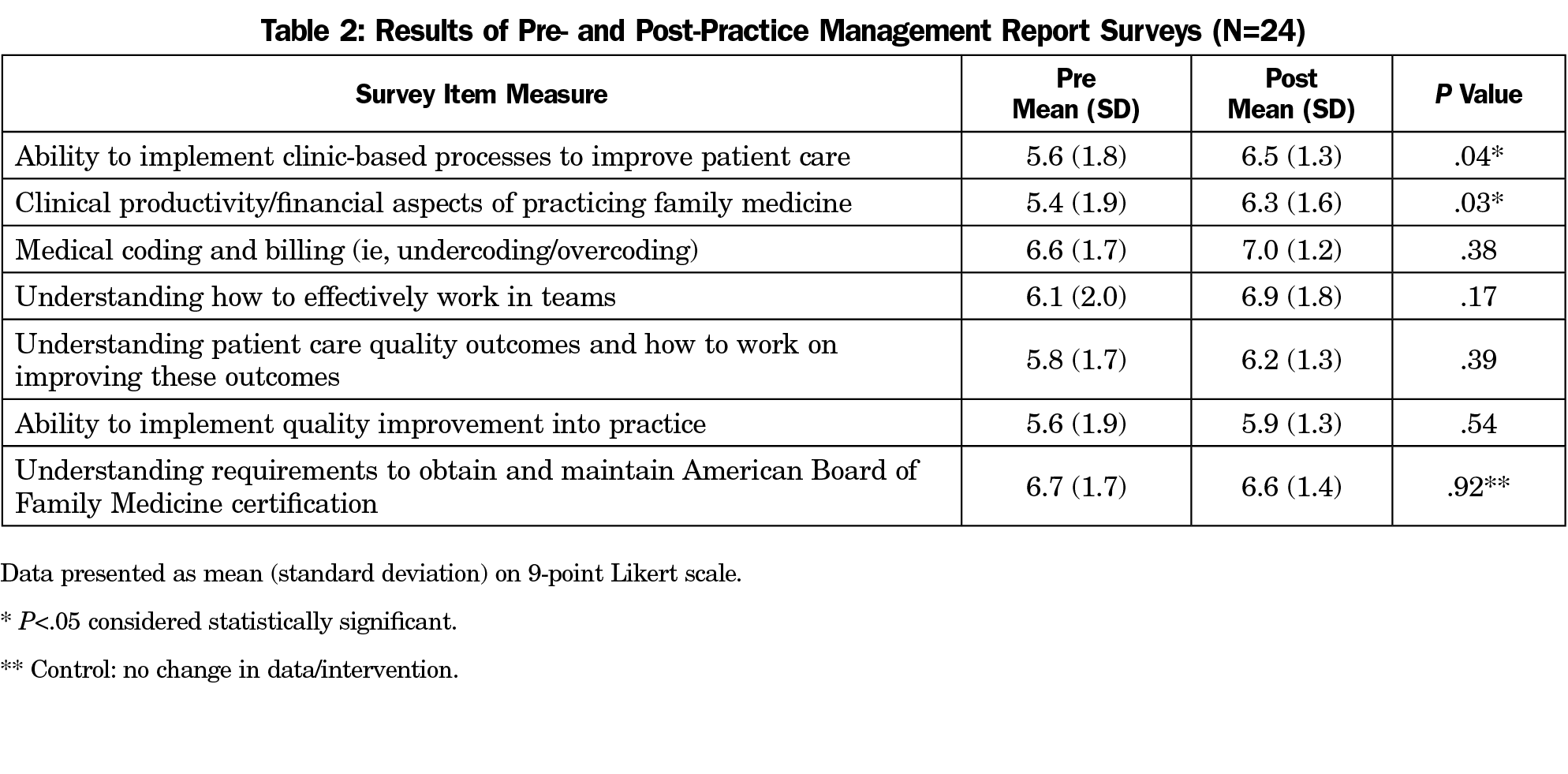

Results: There was significant improvement in the ability to implement clinic-based processes to improve patient care (6.5 vs 5.6; P=.04) and learning about clinical productivity/financial aspects of practicing family medicine (6.3 vs 5.4; P=.03). Other areas had trends of improvement, although not statistically significant.

Conclusions: Providing residents with their clinic practice data, with reference to team practice data and national benchmarks further helps them learn and apply practice management, when superimposed on an existing infrastructure to teach practice management.

In addition to achieving the core competencies during residency training, residents must also learn how to be successful managing their practices after graduation. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Program Requirements in Family Medicine outlines that residents “must continuously improve patient care based on constant self-evaluation and lifelong learning,” and “must receive data on quality metrics and benchmarks related to their patient populations.”1 In the past, it was specified to supply “reports of individual and practice productivity, financial performance, and clinical quality, as well as the training needed to analyze these reports.” This requirement was consistent with the finding that data-driven improvement is one of the base building blocks of high-functioning primary care residency clinics.2

Thus far, the efficacy of this specific approach has not been well established, although there is evidence that practice management curricula can better help prepare family medicine residents for practice.3 There is a paucity of current literature about the effectiveness of practice management residency curricula.4 Residents and practicing family physicians underbill for services rendered, resulting in financial losses.5-7 Structured audits of coding and billing with resident feedback and didactics was associated with reduced undercoding, but it was unclear if the intervention caused this impact.7 A rural background seemed to increase preparedness in nonclinical aspects of practice, including establishing and managing a practice, financial management and business records, and health care reform.8 The goal of this study was to examine the impact of utilizing resident practice management reports (providing individual practice data to residents) to determine if it helps better prepare family medicine residents for future practice.

We provided quarterly resident practice management reports to all residents of the University of Florida Family Medicine residency program, an academic residency program with eight residents per year at the time of this study (see Appendix 1 at https://journals.stfm.org/media/3121/malaty-fam-med-appendix1.pdf). This report included individual coding compliance data (percent of overcoded and undercoded charts) based on review of a subset of their charts by a certified coder. It also included clinical productivity data (number of clinic sessions, visits per session, relative value units [RVUs] per visit, and RVUs per session), with provided comparison to what may be expected upon graduation based on University HealthSystem Consortium (UHC) and Medical Group Management Association (MGMA) data. Individual resident quality data was also provided for chronic care management and preventative health care per Physician Quality Reporting System (PQRS) criteria at that time, analogous to current Merit-based Incentive Program (MIPS; Appendix 1). This quality data was also provided as achieved by clinical teams in the family medicine center, as well as departmental nonresidency clinic rates and national UHC goals. These benchmarks and measures were routinely discussed during regular clinic meetings, at least quarterly, with education provided by the medical director and core residency faculty about how to improve all of these metrics through clinic processes. A certified coder also met with residents at least twice annually to review their coding accuracy with them. This curriculum was in place and unchanged for 2 years prior to surveying residents.

Surveys

We surveyed all residents immediately before they received their first practice management report and after receiving the last quarterly practice management report during the academic year July 2017–June 2018 at the University of Florida Family Medicine residency program. Questions utilized a 9-point Likert scale and assessed preparedness and knowledge of medical coding and billing, productivity/financial aspects of practice, ability to implement quality improvement to their practice population, understanding of working in effective teams, ability to implement clinic-based processes to improve patient care, and understanding of requirements for initial and continued board certification (control measure). We aggregated data from the Likert items into three categories: above average (Likert scores 7-9), average (Likert scores 4-6), and below average (Likert scores 1-3). Our institutional review board granted approval for this study.

Data Analysis

We collected demographic information. The means of each survey response were compared using paired t test before and after utilizing practice management reports, and evaluated for significant differences. We defined significance as P<.05.

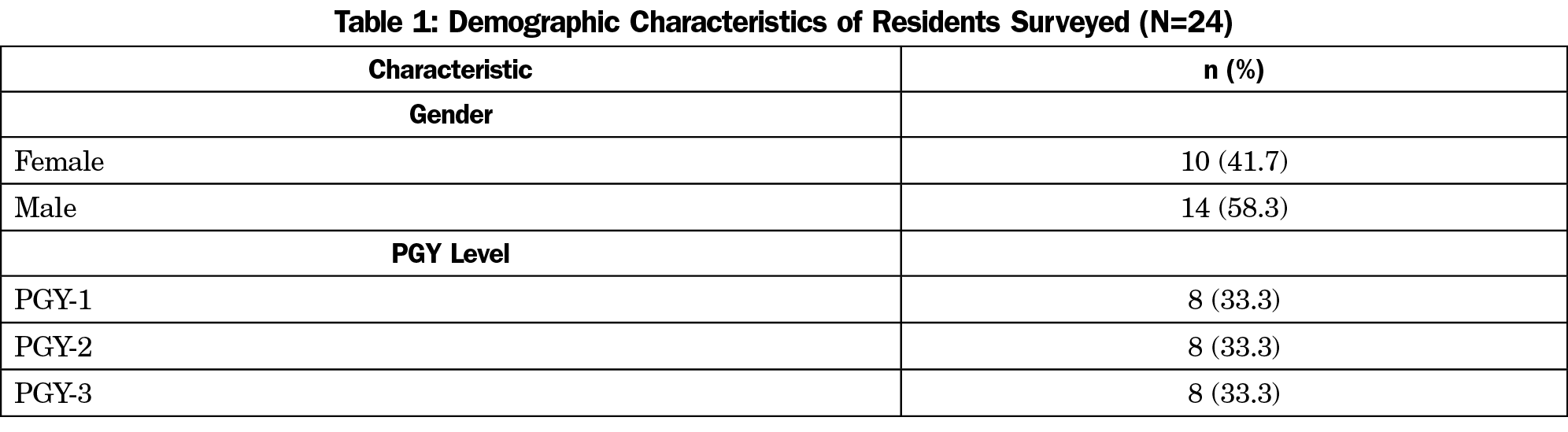

Demographics for surveyed residents demonstrate overall balance of gender and postgraduate year (PGY) level (Table 1). Results of pre- vs postresident surveys after providing practice management reports (Table 2) demonstrate significant improvement in the ability to implement clinic-based processes to improve patient care (6.5 vs 5.6; P=.04), and learning about clinical productivity/financial aspects of practicing family medicine (6.3 vs 5.4 (P=.03). Other areas showed improving trends, but not statistically significant improvement: coding and billing (7 vs 6.6 P=.38); understanding how to work effectively in teams (6.9 vs 6.1; P=.17); understanding patient care quality outcomes and how to work on improving these outcomes (6.2 vs 5.8; P=.39); and ability to implement quality improvement into practice (5.9 vs 5.6; P=.54).

Providing practice management reports improved practice management education during residency when combined with a curriculum, in particular the ability to implement clinic-based processes to improve patient care and learning about clinical productivity/financial aspects of practicing family medicine. This is significant because the curriculum during this time did not change, but the data were used to illustrate how the curriculum pertained to their clinic practice. In addition, after providing resident practice management reports, along with the practice management curriculum, scores in all areas were essentially in the 6-7 range out of a top potential score of 9, corresponding to high average/above average. This is despite surveying all PGY levels, although PGY-1 residents, and to some extent, PGY-2 residents note they had less experience and exposure to practice management, which may lower scores compared to residents nearing graduation. One “control” survey item was included, understanding requirements to obtain and maintain American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) certification. Education about these requirements and discussion of what residents had and had not completed for initial ABFM certification was done during biannual evaluation sessions. This initial ABFM certification data was not included on practice management reports. As expected, this was the only item that did not show any trend towards improvement, which validates the other findings and not simply an overall positive environment at the time of postsurvey. During clinic discussions, faculty felt these reports were highly useful and requested to also receive these practice management reports. Thus, now residents and faculty all receive these reports. A limitation of this study was its sample size, which can negatively impact the ability to detect statistical significance. Although this may limit statistical significance, several significant findings were identified, despite the small sample size, and this sample size allowed detection of educationally significant findings. Thus, it is not felt to impact the overall educational findings of this study.

In conclusion, a practice management curriculum that includes practice data significantly improves family medicine residents’ perception of the value of such a learning experience.

Acknowledgments

Presentation: Portions of this study were presented as “Teaching Residents About Practice Management” at the 2018 Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference, May 5-9, in Washington, DC.

References

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements. https://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Accreditation/Common-Program-Requirements. Accessed July 29, 2019.

- Bodenheimer T, Gupta R, Dubé K, et al. High Functioning Primary Care Residency Clinics – Building Blocks for Providing Excellent Care and Training. Washington, DC: Association of American Medical Colleges; 2016: pp. 1-53.

- Taylor ML, Mainous AG III, Blue AV, Carek PJ. How well are practice management curricula preparing family medicine residents? Fam Med. 2006;38(4):275-279.

- Kolva DE, Barzee KA, Morley CP. Practice management residency curricula: a systematic literature review. Fam Med. 2009;41(6):411-419.

- Young RA, Holder S, Kale N, Burge SK, Kumar KA. Coding family medicine residency clinic visits, 99213 or 99214? A residency research network of texas study. Fam Med. 2019;51(6):477-483. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2019.862757

- Evans DV, Cawse-Lucas J, Ruiz DR, Allcut EA, Andrilla CH, Norris T. Family medicine resident billing and lost revenue: a regional cross-sectional study. Fam Med. 2015;47(3):175-181.

- Skelly KS, Bergus GR. Does structured audit and feedback improve the accuracy of residents’ CPT E&M coding of clinic visits? Fam Med. 2010;42(9):648-652.

- Szafran O, Crutcher RA, Woloschuk W, Myhre DL, Konkin J. Perceived preparedness for family practice: does rural background matter? Can J Rural Med. 2013;18(2):47-55.

There are no comments for this article.