Background and Objectives: Older adults are the fastest growing subset of the population and residency training in the basic concepts of care to the older adult is limited. We created a 1-day interactive training program, Advanced Geriatric Evaluation Skills (AGES), to upskill first-year primary care residents in the care of older adults.

Methods: An interprofessional faculty team developed and taught the IRB-approved course to a convenience sample of family medicine and internal medicine interns in 2017, 2018, and 2019. Topics addressed common geriatric presentations seen in the outpatient setting. The faculty provided useful tips and hints for successful workup, diagnosis, and treatment.

Results: Over the 3 years, 56 of the 135 (41%) first-year primary care residents participated. Residents reported that the course was well organized, relevant, and well taught, and they appreciated the dedicated time to focus on caring for older adults. During 2019, residents completed a pre- and posttest with 25 multiple-choice questions. The average score on the pretest was 76% and the average on the posttest was 88%. Ninety percent of the residents improved their score from the pre- to the posttest.

Conclusions: The development of an AGES program provided a structured geriatric didactic curriculum for primary care residents. The course was well received by the residents, was reported to be relevant and timely, and resulted in increased knowledge in the care of older adults in the outpatient setting.

By 2030, nearly 20% of the US population will be over the age of 65.1 There are not nearly enough specialty geriatricians to care for this population so most of the primary health care for these older adults will be provided by family physicians and general internists who need to be prepared for this aspect of their practice. Despite this, residency training in the basic concepts of care to the older adult is limited. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) specifies that by the end of their residency, family medicine residents must have at least 100 hours (or 1 month) or 125 patient encounters dedicated to the care of the older patient which must incorporate principles of geriatric care and must occur across a continuum of settings including hospitals, long-term care facilities, and rehabilitation facilities.2 Currently, there is no specific mention of care for older adults or training in geriatrics in the required internal medicine curriculum. Given the crowded curricula in primary care training programs, training in geriatric medicine is often limited.

One model for enhancing clinical training is the intensive skill-building course known as Advanced Life Support in Obstetrics (ALSO). Using ALSO as a model, we created a 1-day course that teaches residents essential competencies in the care of older adults. Topics were agreed upon by course faculty and from references that define essential training in geriatrics.3 The course, Advanced Geriatrics Evaluation Skills (AGES), helps primary care residents develop the essential knowledge, confidence, and skills needed to provide optimal care for older adults.

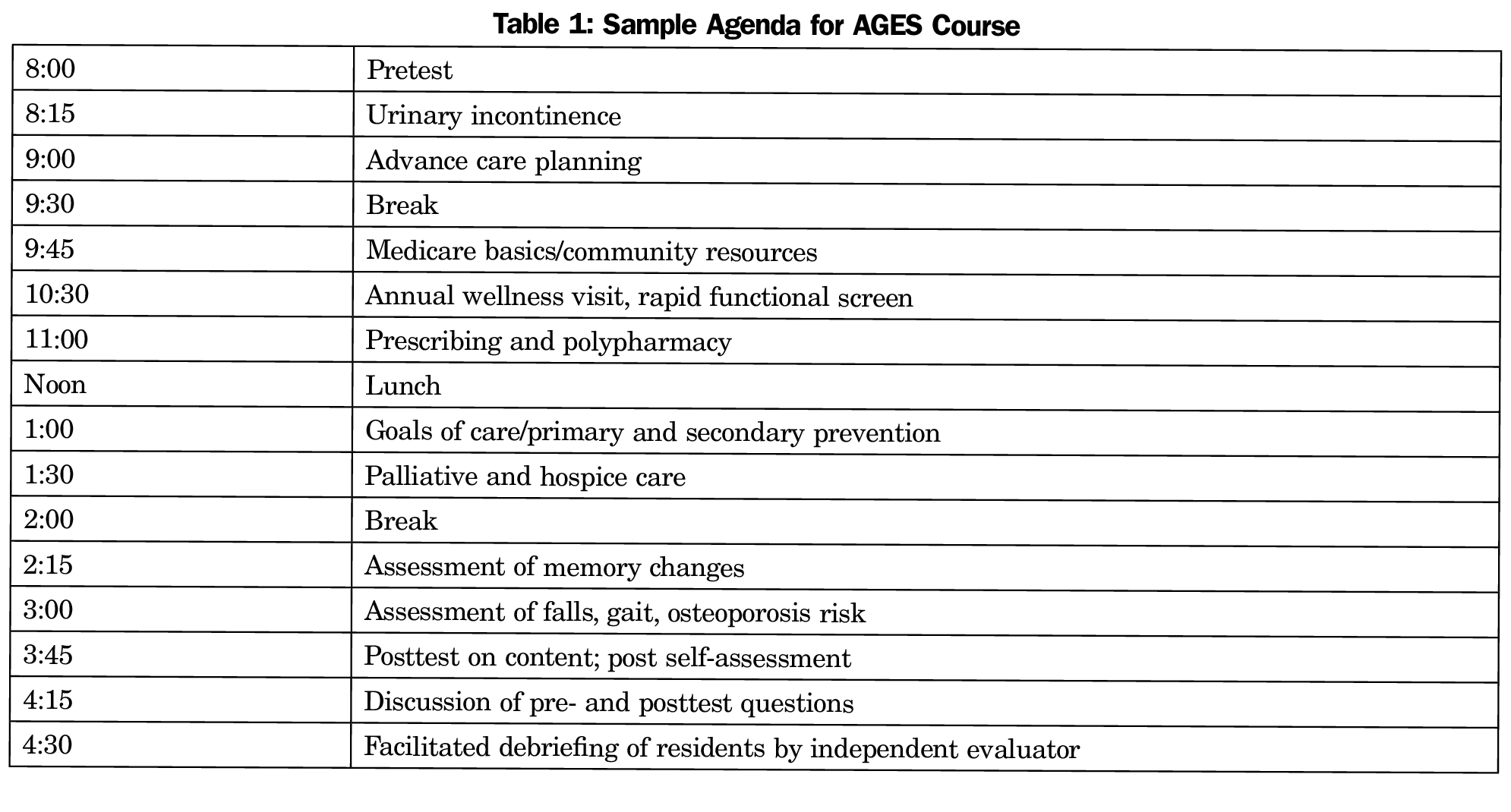

University of North Carolina (UNC) at Chapel Hill family medicine (FM) and internal medicine (IM) first-year residents participated in a 1-day interactive training program on geriatrics evaluation skills to use in the primary care setting. The Office of Human Research Ethics reviewed this curriculum evaluation and determined it to be exempt from further review. The program was presented midway through the academic year in 2017, 2018, and 2019 to a convenience sample of family medicine and internal medicine residents, who took the course separately due to scheduling practicalities. An interprofessional faculty team experienced with geriatrics in the primary care setting, consisting of geriatricians, pharmacists, social workers, and physical therapists taught the course. The faculty team developed the content of the workshop based on generally accepted competencies in geriatrics.4 The curriculum focused on performing geriatric assessment in primary care, including content on prevention and annual wellness visits, advance care planning, assessing cognition, function, falls, urinary incontinence, prescribing and deprescribing, the basics of Medicare, community resources, and palliative and hospice care (Table 1). Instructors taught residents in minilectures that were interactive, case-based, and often involved residents practicing skills such as functional assessments or cognitive screening tests. Instructors also incorporated tips for using these skills in routine office visits. A dropbox of online information was available for residents for later use and included the slides, background articles, and clinical tools.

Immediately after completing the course, residents participated in a facilitated debriefing with an independent evaluator to gather qualitative responses from the learners. We used this feedback to make improvements in the course curriculum and teaching strategies. Residents also completed a retrospective self-assessment on their likelihood to apply specific skills in the care of older adults as well as their perceived current skill level. For the 2019 course, residents completed a pre- and postcourse knowledge assessment. The test was comprised of 25 questions, covering the course content areas. Questions were obtained in equal numbers from the publicly accessible American Geriatrics Society Geriatric Review Syllabus and UCLA Geriatric Medicine Fellow’s Knowledge Examination.5-6

During the 3 years the AGES course was offered, 17 residents in 2017 (11 FM, 6 IM), 16 residents in 2018 (11 FM, 5 IM), and 23 residents in 2019 (9 FM, 14 IM) participated. This was 56/135 (41%) of the total available FM and IM first-year residents. Availability of IM residents was limited due to scheduling conflicts, but after positive feedback, the IM program made the effort to excuse more IM residents from clinic so they could attend, which increased the rate of participation. FM residents attended during dedicated didactic time, so they were more able to participate.

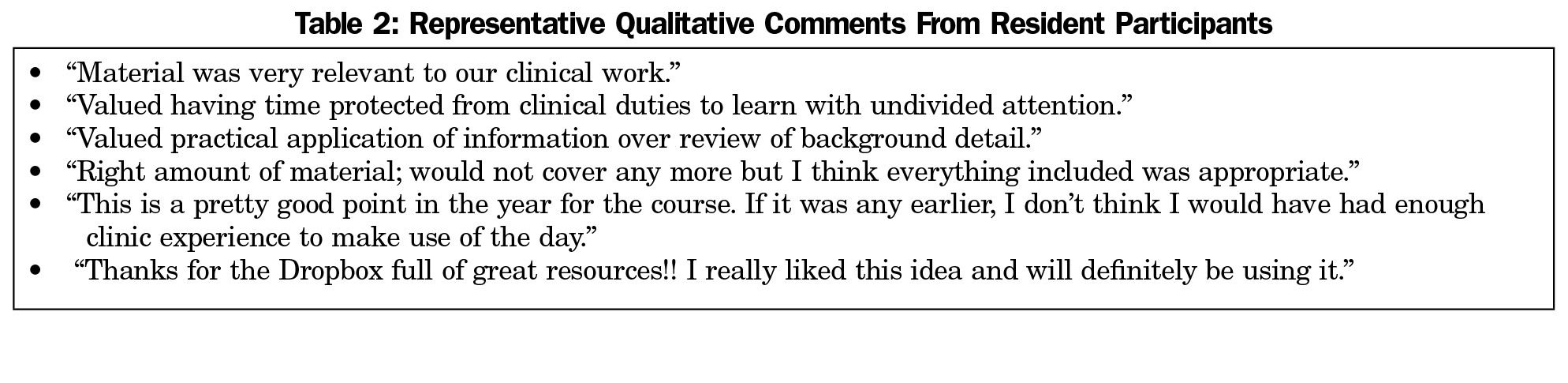

Resident feedback was collected by a third party. The feedback showed the course was well organized, relevant, well taught, and dedicated protected time away from clinical duties was appreciated (Table 2). During 2017, a portion of the curriculum included standardized geriatric patients which the residents did not feel provided additional value. Given this, and the extra logistics involved, this feature was dropped. The combination of PowerPoint didactics, active learning with standardized cases, and small groups kept the residents engaged and was reported as a positive experience. After completing a full day of interactive, dedicated teaching in outpatient care of older adults, the first-year residents reported increased knowledge in assessing common clinical geriatrics problems.

During 2019, 23 residents completed the pretest and 21 residents completed the posttest. The pretest mean correct score was 76% (19/25), with a range of 60% to 88% correct. The posttest mean correct score was 88% (22/25). Nineteen of the 21 residents who completed both the pre- and posttests improved their scores. Most errors on these tests were related to the prescribing questions.

On completion of the AGES training, the residents reported feeling more knowledgeable and found the most useful topics to be Medicare/Medicaid, deprescribing, urinary incontinence, goals of care, advanced care planning, and falls assessment. The learners requested more content on communication skills for goals of care conversations, specifics around palliative care, and more on the management of delirium and dementia in the outpatient setting. An additional benefit of this workshop was modeling team-based interdisciplinary care for geriatric patients as the course faculty included pharmacists, physicians, physical therapists, and social workers. The range in the residents’ scores on the 2019 pretest reflects the varying exposure to geriatric concepts during their medical school training. Since the prescribing questions were the most challenging for the residents, in future years more emphasis will be placed on reviewing common medication errors when caring for older adults.

The engagement, value, and knowledge acquisition reported by the residents reflects appropriate training activities for their early stage of training. This provides a foundation upon which more advanced training can affect actual practice and impact patient care. Our preliminary qualitative results suggest that the AGES training is likely to be useful to participants’ clinical work.

This study is limited by the small number of primary care residents who were able to participate. In future presentations of this curriculum, there may be value in expanding the course to include other interdisciplinary health profession learners. This would broaden the kind of questions asked, provide different perspectives, and spread more knowledge. Other steps may include a refresher course such as has been used in other models of topic-specific education.6 This might include case-based learning appropriate for second- or third-year residents.

We hope to disseminate this curriculum to other programs, including those that may not have faculty specially trained in geriatrics. The ALSO course for obstetrical care models the effectiveness of standardized courses. We will develop a course manual to guide teaching and testing, refine course content based on feedback, and make the materials available to other training programs. Barriers to adoption by other training programs include a limited number of faculty who are comfortable teaching geriatric topics, especially since success includes small group discussion. Finding time for busy first-year residents to attend a day-long course requires support from the program director. The course requires a lead faculty member to oversee the course throughout the day while other teaching faculty attend only when they are actively teaching, which averaged about an hour per faculty.

The development of an AGES program provided a structured outpatient geriatric curriculum for new primary care residents, consistently increasing the knowledge base for participating first-year residents. This helps build a foundation upon which they can develop needed clinical skills in the care of older adults.

Acknowledgments

The development of this curriculum was funded with support from the North Carolina Area Health Education Center Campus Innovation Grant Program–2016-2017.

Presentations: Preliminary work on the AGES curriculum was presented as a poster at the May 2018 Annual Scientific Meeting of the American Geriatrics Society in Orlando, Florida. (Warshaw G, Brown M, Dale M, Halpert K. Advanced Geriatrics Evaluation Skills (AGES): A new intensive geriatrics skill course for primary care residents. J Amer Geriatri Soc, 2018; 66(suppl. 2):S71.)

References

- US Census Bureau. The Next Four Decades: The Older Population in the United States: 2010 to 2050. Washington, DC: Us Department of Commerce; May 2010. https://www.census.gov/prod/2010pubs/p25-1138.pdf. Accessed February 1, 2019.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine, effective July 1, 2018. Chicago: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/120FamilyMedicine2018.pdf. Accessed September 16, 2018.

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Recommended Curriculum Guidelines for Family Medicine Residents Care of Older Adult, revised June 2015. Leawood, KS: AAFP. https://www.aafp.org/dam/AAFP/documents/medical_education_residency/program_directors/Reprint264_Older.pdf. Accessed Decemenber 11, 2019.

- Williams BC, Warshaw G, Fabiny AR, et al. Medicine in the 21st century: recommended essential geriatrics competencies for internal medicine and family medicine residents. J Grad Med Educ. 2010;2(3):373-383. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-10-00065.1

- Tuqan AT, Lee M, Weintraub NT, Reuben DB. Development and validation of a geriatrics knowledge test to evaluate geriatrics fellowship programs. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2017;65(11):2535-2538. https://doi.org/10.1111/jgs.15068

- Durso SC, Sullivan GM. GRS - Geriatrics Review Syllabus. New York: American Geriatrics Society; 2013.

- Lee L, Hillier LM, Weston WW. “Booster Days”: an educational initiative to develop a community of practice of primary care collaborative memory clinics. Gerontol Geriatr Educ. November 7, 2017;1-16. https://doi.org/10.1080/02701960.2017.1373350

There are no comments for this article.