Background and Objectives: Many residency programs are developing resident wellness curricula to improve resident well-being and to meet Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education guidelines. However, there is limited guidance on preferred curricular components and implementation. We sought to identify how specific driving factors (eg, having an identified wellness champion with a budget and protected time to develop wellness programs) impact implementation of essential elements of a resident wellness curriculum.

Methods: We surveyed 608 family medicine residency program directors (PDs) in 2018-2019 on available resources for wellness programs, essential wellness elements being implemented, and satisfaction with wellness programming; 251 PDs provided complete responses (42.5% response rate). Linear and logistic regressions were conducted for main analyses.

Results: Having an identified wellness champion, protected time, and dedicated budget for wellness were associated with greater implementation of wellness programs and PD satisfaction with wellness programming; of these, funding had the strongest association. Larger programs were implementing more wellness program components. Program setting had no association with implementation.

Conclusions: PDs in programs allocating money and/or faculty time can expect more wellness programming and greater satisfaction with how resident well-being is addressed.

There is a well-documented crisis of medical student, resident, and physician burnout across specialties1-3 with associated sequela of increased attrition, lower productivity, high costs of physician turnover, and severe depression and suicidality.4,5 Paradoxically, family physicians may report higher symptoms of burnout compared to other specialties,3 but family medicine residents report lower levels of specialty choice regret.6 Given the scope of the problem, important stakeholders at all levels are developing and implementing burnout prevention and well-being programs. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) requires a focus on well-being in the Common Program Requirements, which state:

Psychological, emotional, and physical well-being are critical in the development of the competent, caring and resilient physician…. Programs, in partnership with their Sponsoring Institutions have the same responsibility to address well-being as they do to evaluate other aspects of resident competence.7

Despite this, well-being requirements are nebulous, and there is no strong evidence-based consensus on development or implementation of efficacious well-being and burnout prevention curricula in GME.

The Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors (AFMRD) recently produced the Physician Wellness Task Force’s Well-Being Action Plan.8 With this, evidence-based curricular recommendations were distributed to program directors (PDs) to promote well-being in residency. The action plan included items identified as positively impacting well-being in residency training according to existing literature.9,10 This comprehensive list of curricular elements, however, did not include guidelines on prioritization or implementation strategies—important considerations given competing demands within GME.11

Using the AFMRD Well-being Action Plan as a foundation, the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) Task Force on Resident Wellness Curriculum conducted a systematic inquiry using a Delphi technique to prioritize wellness curriculum elements. We used the term wellness to refer to programs, and well-being to refer to outcomes among individuals.12 A Delphi technique is an approach that utilizes a panel of experts on a topic who are taken through a series of structured iterative surveys to arrive at a consensus. Through the process, an expert consensus concluded the following elements were essential12:

- Make wellness part of the residency vocabulary;

- Create a safe culture encouraging disclosure of resident struggles;

- Provide access to mental health treatment;

- Include recurring or longitudinal wellness activities; and

- Identify a wellness champion.

Reflected in the elements are opportunities for intervention across multiple domains, including culture, leadership, policies, support resources, curriculum, and faculty development.13

This present study sought to clarify the extent to which these practices are being implemented among FM programs nationally and to identify necessary programmatic resources for implementation of satisfactory wellness curricula in residency training. Based on models of organizational change that recommend consideration of driving forces and barriers to implementation (eg, support from leadership, expertise, desire, funding),14,15 we specifically sought to examine how certain factors (having an identified wellness champion with a budget and protected time to develop wellness programs) impact implementation of essential elements of residency wellness curricula. To our knowledge, this is the first paper to quantify current practices to address resident well-being nationally and identify key characteristics of satisfactory wellness programming. Along with expert consensus from the Delphi study, the results of this study can help residency programs prioritize initiatives and resources that lead to successful implementation of wellness curricula.

Procedures

We developed survey questions based on results of the Delphi study described herein.12 The questions were part of a larger survey conducted by the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA). The methodology of the CERA survey has been described previously.16 The CERA steering committee evaluated proposals for the program directors (PD) special survey about wellness/burnout/fatigue on consistency with the overall project aim, readability, and existing evidence of reliability and validity. Pretesting of questions was completed with family medicine educators who were not in the target population by both the CERA steering committee and our research team. We modified questions following pretesting for flow and readability. Invitations to participate were delivered via e-mail with a SurveyMonkey web link, with data collection occurring from December 2018 to January 2019. We subsequently sent seven follow-up emails encouraging nonrespondents to participate. The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved the project in November 2018.

Participants

The sampling frame for the survey was all ACGME-accredited US family medicine residency PDs as identified by the AFMRD. At the time of the survey, there were 624 PDs, of whom 16 opted out of CERA survey participation. The survey was emailed to 608 individuals; 18 emails were undeliverable. The overall response rate was 45.4% (268/590). An additional 17 programs did not complete wellness items from the survey and were excluded from the analyses, leaving a final sample of 251/590 (response rate of 42.5%) for the analyzed data.

Measures

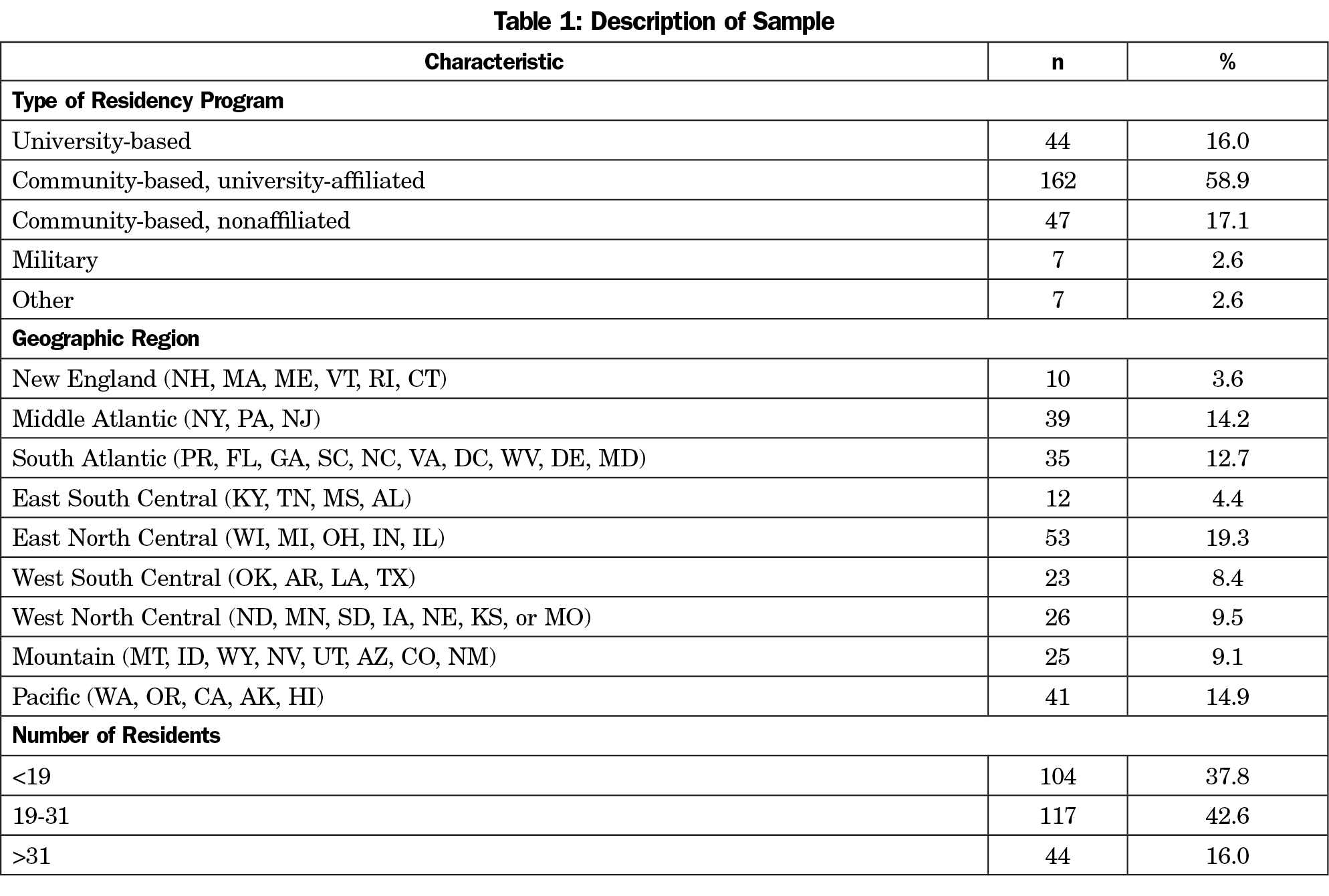

The survey included demographic characteristics regarding each residency program (Table 1) and 11 questions focused on which specific elements of wellness existed in the PD’s program (if at all). We used the CERA survey response categories for program size for our analyses and created a new categorization for program setting to contrast programs described as “university-affiliated,” “university-based,” or “neither” to form meaningful, equally-sized groups for analyses (see Table 1 for original CERA categorizations). Additionally, we asked PDs to rate their satisfaction with how their program addresses resident well-being on a 4-point Likert scale.

Analysis

To identify current practices and resources needed for implementation of wellness curricula, we hypothesized the following:

- Items recognized as “most essential” resident wellness curriculum elements are currently not being implemented by a majority of programs (less than 50%).

- Consistent with models of organizational change, programs with an identified champion or wellness program resources (ie, protected time and budget) are implementing more recommended elements of a wellness curriculum as compared to programs without a champion or resources for development of wellness initiatives. Programs with both a champion and resources will be most successful in implementing recommended elements.

- University-based and university-affiliated programs implement more elements of a wellness curriculum as compared to nonuniversity programs, as the former are likely to have greater access to expert faculty and other resources.

- Larger residency programs are implementing more recommended elements of a wellness curriculum.

We assigned numerical values to wellness questions reflecting the essential elements, which were summed to calculate a total wellness score (TWS; Table 2). The TWS ranged from 0-12. TWS numerical values were determined by group consensus. When possible, the program was assigned zero points for absence of the wellness curriculum element and one point for the presence of the element (eg, mental health treatment availability for residents). However, some elements can be implemented to different extents (eg, weekly support group vs wellness afternoon once annually). In these cases, one point was assigned for lower degree of implementation, and two points were assigned for more extensive implementation.

We used linear regression to model associations between independent variables and TWS; and we used logistic regression to compute odds ratios to estimate the associations between independent variables and PD satisfaction with wellness program implementation. Statistical assumptions for normality and multicollinearity were met. We set statistical significance at α=0.05, recognizing that tests of statistical significance are approximations that serve as aids to interpretation and inference. Stata software (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas) was used for analysis.

Hypothesis 1: Items recognized as “most essential” resident wellness curriculum elements are being implemented by less than 50% of programs.

In contrast to the first hypothesis, more than 50% (n=145) of the programs surveyed are including the essential elements from the Delphi study. Mean and median of the TWS was 10. See Figure 1 for percentage of programs scoring 0, 1, or 2 on each essential element.

Hypothesis 2: Programs with an identified champion or wellness program resources or both are implementing more recommended elements of a wellness curriculum as compared to programs without a champion or resources.

Exploratory analysis examining the programs with the lowest TWS confirmed the hypothesis that among programs in the lowest quartile of the TWS (n=63), 22% (n=13) had no wellness champion in their program, and 32% (n=20) allocated neither time nor budget for wellness activities. Among programs in the lowest 10% of the TWS (n=29), 34% had no wellness champion (n=9), and 45% (n=13) allocated neither time nor budget for wellness activities.

Hypothesis 3: University-based and university-affiliated programs implement more elements of a wellness curriculum as compared to nonuniversity programs.

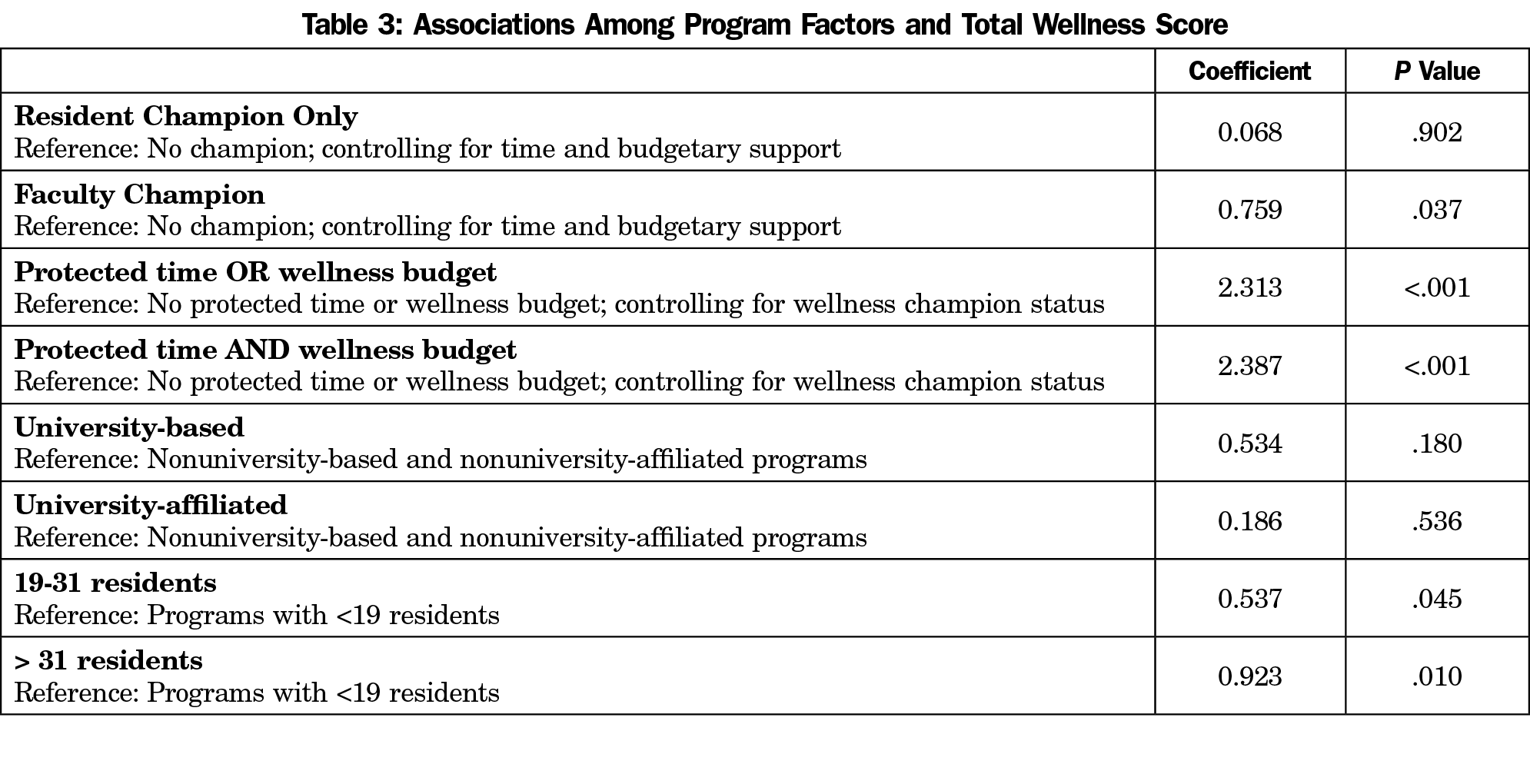

Multiple linear regressions were calculated to predict the TWS based on the type of the program (university-based, university-affiliated, and nonuniversity programs). No significant regression equation was found for program setting, F (2, 252)=0.92, P=.40, R2=0.25 (Table 3).

Hypothesis 4: Larger residency programs are implementing more recommended elements of a wellness curriculum.

Multiple linear regression for program size (fewer than 19 residents, 19-31 residents, or more than 31 residents) found significant differences, F (2, 250)=3.91, P=.03, R2 =0.03, indicating 3% of the variation of the TWS can be explained by this model. Programs with 19-31 residents and greater than 31 residents had higher TWS (Table 3).

Notably, no demographic variables used in our analyses were significantly different between the programs responding to wellness items and those not responding to wellness items.

Exploratory Analyses

Results of the logistic regression indicated significant, independent associations between PD satisfaction with their programs’ approach to wellness and both the type of wellness champion and the level of programmatic support (Table 4). Controlling for level of support, respondents were 10.2 times more likely to endorse satisfaction if a resident was the sole wellness champion as compared to having no champion. Having a faculty champion was associated with 4.6 higher odds of reporting satisfaction as compared to programs with no champion. Programs with both protected time and a wellness budget were associated with 9.1 higher odds of PD satisfaction as compared to having neither, while controlling for the presence of a wellness champion.

This study aimed to quantify current practices in resident wellness program implementation and program factors associated with implementation of essential elements of a wellness curriculum identified in a previous Delphi study. Over 40% of programs reported implementing nine or more of the essential elements. Based on factors such as leadership support, subject matter expertise, dedicated time, and financial resources as fundamental for building wellness programs,15 our hypothesis that residency programs with an identified champion or resources for wellness programming would be implementing more of the essential elements of a wellness curriculum, as compared to those programs without these, was strongly supported. Moreover, we noted a clear relationship between a program implementing essential elements and having both a champion and resources. Programs with the lowest TWS were less likely to have a champion with dedicated time or budget for wellness. Having a resident champion (as opposed to a faculty champion) did not significantly predict a higher wellness score; however, it was significantly associated with PD satisfaction with their wellness program, suggesting that PDs place a high value on resident involvement in wellness programming. Our results further revealed that wellness program resources (ie, a budget) were an even stronger predictor of a higher TWS than a dedicated champion alone. Thus, funding of specific wellness activities within the residency program is the most important factor for increasing TWS and PD satisfaction with wellness programming. To our knowledge, this is the first research to clearly demonstrate the importance of a budget dedicated to resident wellness programs, beyond a dedicated champion. Successful program implementation appears to require a dedicated person, protected time, and financial resources.

Other program factors that may affect access to resources yielded mixed results. Whereas program setting had no significant associations on the quantity of wellness elements in place, program size was related to implementation, such that programs with more than 19 residents had higher TWS than programs with fewer than 19 residents. This may be due to greater access to resources based on program size and economies of scale with larger programs having overall larger budgets.

Finally, we explored how PD satisfaction with wellness was related to implementation of a wellness curriculum. Programs with more elements of a wellness curriculum have greater PD satisfaction with wellness. Quantity may not be synonymous with quality; however, it is likely that quantity is linked to a culture in which well-being is considered important and is addressed routinely. We suspect programs with a higher TWS are actively fostering a culture of wellness, which promotes the well-being of the individuals in these programs.

This study offers the first clear evidence for program directors to cite when petitioning for and securing human and financial resources from department chairs and sponsoring institutions on behalf of their residents. These findings provide leverage for advocacy efforts to strengthen ACGME’s wellness initiatives to go beyond the general guidance it currently offers. This evidence supports practical initial steps that accrediting organizations and professional groups can use to implement policies for successful wellness programs. These evidence-based steps include protected curriculum activity time, dedicated faculty, and financial support specifically allocated to resident well-being.

Several limitations exist in this study and restrict conclusions accordingly. While the response rate for the survey was commendable, there remain over 50% of programs without data, and we cannot reliably compare differences between responding and nonresponding programs. Perhaps the greatest limitation of the study lies in its scope and inability to draw conclusions about whether the TWS predicts objective or subjective measurement of resident well-being in these programs. Longitudinal and prospective studies evaluating whether intentional well-being policies and programming within a residency are effective at mitigating burnout and improving resident well-being need to be funded. We also must consider whether programs allocating time and money to resident well-being may have a response bias to report higher satisfaction. It also is possible that self-report data from PDs—who are responsible for ensuring compliance with ACGME requirements to address resident well-being—may be biased.

Although we conducted this study among FM residency programs, the problem of resident well-being is not specific to family medicine as a specialty. All GME programs and sponsoring institutions are compelled to address resident well-being by the Common Program Requirements.7 However, family medicine residencies are uniquely positioned to advance curriculum and research on physician-in-training well-being. ACGME requirements specify that FM residency programs include faculty members dedicated to the integration of behavioral health into the education program.17 For many programs this means the inclusion of behavioral science faculty who by training have expertise in resilience and well-being. Consequently, FM residency programs, as compared to other disciplines, have the faculty expertise, cultural milieu, and curriculum to expand wellness within the physician workforce and facilitate these pioneering research and curricular initiatives across medical specialties.

The field would benefit from using this research as a benchmark for evaluating the robustness of wellness programming within residencies and move on to the more complex work of exploring linkages between programmatic efforts (eg, implementation of essential wellness curricula) and well-being outcomes. Additional reflection or evaluation of the culture and learning environment of the larger systems within which programs operate should be done to better understand the impact of programmatic interventions.18,19

In summary, program size and resource allocation are related to wellness curriculum implementation. PDs in programs which allocate money and/or time to wellness curricula can expect greater programming and satisfaction with how resident well-being is addressed. Given the moral imperative to address resident well-being, the ACGME requirements to develop and implement policies and activities to mitigate burnout among residents is laudable. This study advances the limited empirical knowledge to date by offering programs concrete guidance on the importance of allocating resources (protected time and financial support) in order to satisfactorily implement wellness curricula.

References

- Dyrbye LN, West CP, Satele D, et al. Burnout among U.S. medical students, residents, and early career physicians relative to the general U.S. population. Acad Med. 2014;89(3):443-451. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000134

- Ishak WW, Lederer S, Mandili C, et al. Burnout during residency training: a literature review. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(2):236-242. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-09-00054.1

- Shanafelt TD, Boone S, Tan L, et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172(18):1377-1385. https://doi.org/10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199

- Dyrbye L, Shanafelt T. A narrative review on burnout experienced by medical students and residents. Med Educ. 2016;50(1):132-149. https://doi.org/10.1111/medu.12927

- Shanafelt T, Goh J, Sinsky C. The business case for investing in physician well-being. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177(12):1826-1832. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.4340

- Dyrbye LN, Burke SE, Hardeman RR, et al. Association of clinical specialty with symptoms of burnout and career choice regret among US resident physicians. JAMA. 2018;320(11):1114-1130. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2018.12615

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Common Program Requirements. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRs_2017-07-01.pdf. Accessed May 3, 2019.

- Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors Physician Wellness Task Force. Well-Being Action Plan for Family Medicine Residencies: Creating a Culture of Wellness. 2017. Available to members at afmrd.org.

- Raj KS. Well-being in residency: a systematic review. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(5):674-684. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-15-00764.1

- West CP, Dyrbye LN, Erwin PJ, Shanafelt TD. Interventions to prevent and reduce physician burnout: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet. 2016;388(10057):2272-2281. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(16)31279-X

- Winkel AF, Nguyen AT, Morgan HK, Valantsevich D, Woodland MB. Whose problem is it? The priority of physician wellness in residency training. J Surg Educ. 2017;74(3):378-383. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsurg.2016.10.009 PMID:27810465

- Penwell-Waines L, Runyan C, Kolobova I, et al. Making sense of family medicine resident curricula: A Delphi study of content experts. Fam Med. 2019;51(8):670-676. https://doi.org/10.22454/FamMed.2019.899425

- Konopasek L, Slavin S. Addressing resident and fellow mental health and well-being: what can you do in your department? J Pediatr. 2015;167(6):1183-4.e1. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jpeds.2015.09.037

- Varkey P, Antonio K. Change management for effective quality improvement: a primer. Am J Med Qual. 2010;25(4):268-273. https://doi.org/10.1177/1062860610361625

- Ey S, Moffit M, Kinzie JM, Brunett PH. Feasibility of a comprehensive wellness and suicide prevention program: A decade of caring for physicians in training and practice. J Grad Med Educ. 2016;8(5):747-753. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-16-00034.1

- Mainous AG III, Seehusen D, Shokar N. CAFM Educational Research Alliance (CERA) 2011 Residency Director survey: background, methods, and respondent characteristics. Fam Med. 2012;44(10):691-693.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/120_FamilyMedicine_2019.pdf?ver=2019-06-13-073936-407. Accessed September 26, 2019.

- Card AJ. Physician burnout: resilience training is only part of the solution. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):267-270. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.2223

- Jennings ML, Slavin SJ. Resident wellness matters: optimizing resident education and wellness through the learning environment. Acad Med. 2015;90(9):1246-1250. https://doi.org/10.1097/ACM.0000000000000842

There are no comments for this article.