Background and Objectives: Medical schools aim to admit talented learners who are honest, patient centered, and caring, in addition to possessing the required cognitive skills. The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) describes core competencies for entering medical students in three categories: science, preprofessional, and thinking and reasoning. The authors sought to determine desired characteristics of medical school applicants at a rural, community-based medical school in light of the published core competencies.

Methods: This qualitative study involved an analysis of data from discussion groups, all from a convenience sample of participants. The authors led the discussion groups, and large sticky note pads and pens were provided to scribe responses. Group members were given the prompt, “What do you see as traits or characteristics of your ideal doctor?” We used a content analysis approach to analyze the data.

Results: The total number of responses across groups was 243, representing 15 unique characteristics. The 15 characteristics, listed in decreasing order of frequency, included good communicator, knowledgeable, dedicated, compassionate, respectful, community oriented, well rounded, patient, team player, available, leader, positive attitude, equal treatment, prevention focused, and urgency when needed for patient care. Of the top characteristics with 20 or more responses, alignment with AAMC competencies was noted, but less so with being community oriented as defined by study participants.

Conclusions: This study demonstrates that there are unique characteristics that a rural community and its medical school consider when admitting applicants to their medical program. Further research is needed to explore the need for additional competencies for rural medical schools to consider for entering medical students.

Medical schools aim to admit talented learners who are honest, patient centered, and caring, in addition to possessing the required cognitive skills.1 The Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) describes core competencies for medical students in three categories: science, preprofessional, and thinking and reasoning.2 Preprofessional competencies include service orientation, social skills, cultural competence, oral communication, resilience, and dependability. We hypothesized that medical schools with a rural presence recruit applicants with backgrounds and characteristics that specifically foster the desire to practice rural medicine.3-5 Brody, recognized by the American Academy of Family Physicians as number two in the nation and number one in the state in producing graduates pursuing family medicine,6 only admits students from the state of North Carolina.

Prior successful initiatives aimed at increasing the rural physician workforce have included programs oriented toward rural practice that were operated by medical schools located in urban settings.7 Several urban medical schools have also described success with increasing the number of graduates entering rural practice by opening satellite campuses in rural areas.8-11 For campuses or schools located in rural areas, there is a need to identify applicants who will be actively engaged in the communities in which they live, embarking to make positive change. Considering the nation-wide decline in medical student applicants who have a rural upbringing,12 there must be an intentional approach to recruit the rural applicant to medical school with attention paid to rural background and other characteristics that may lead to the desire to practice rural medicine.3-5, 13 Because of Brody’s unique orientation toward primary care and service to rural communities, we sought to determine how expectations for applicants among academic personnel, and community members overlap with AAMC core competencies.

Participants

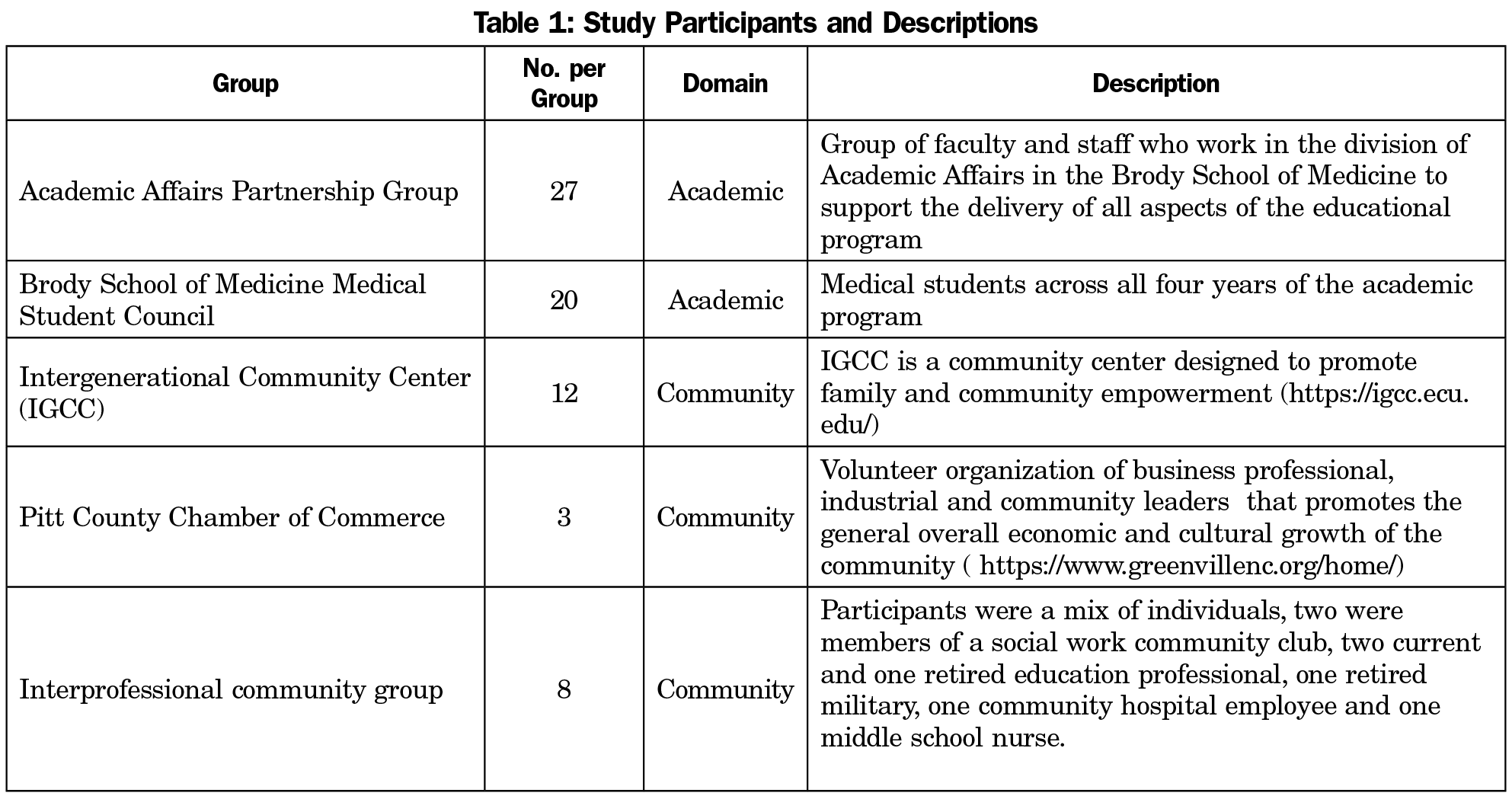

This qualitative study utilized a convenience sample of academic and community members in rural eastern North Carolina. The study coordinator (K.L.) worked with the director of outreach for the school of medicine to identify and contact community participants. There were no incentives for participation. Choice of study participants was based on prior knowledge of and interaction with the participants in other community settings. Participants were recruited through phone or email contact by the study coordinator. The two academic discussion groups included Brody faculty, staff and students. Table 1 gives a description of the study participants.

Procedure

The Institutional Review Board at East Carolina University approved this study. After participants were identified, each group was scheduled to meet separately, so there was no mixing of participants. At each discussion session, researchers explained the intent of the project, including an overview of the current applicant screening process at Brody. Discussion groups were led by authors (K.M.C., K.L.). Large sticky note pads and pens were provided to scribe responses. Group members were given the prompt, “What do you see as traits or characteristics of your ideal doctor?” They were not provided the AAMC competencies. Participants in each group were able to scribe and share for 1 hour. Discussion group results were reviewed, coded, and themed by authors (K.M.C., K.L.), and any disagreements resolved by one author (P.A.). The authors achieved alignment with the AAMC competencies by consensus, with disagreements also resolved by one author (P.A.).

Analysis

We used a summative approach to content analysis to analyze the data recorded on sticky notes.14,15 We then compared the results to the AAMC core competencies for entering medical students.2

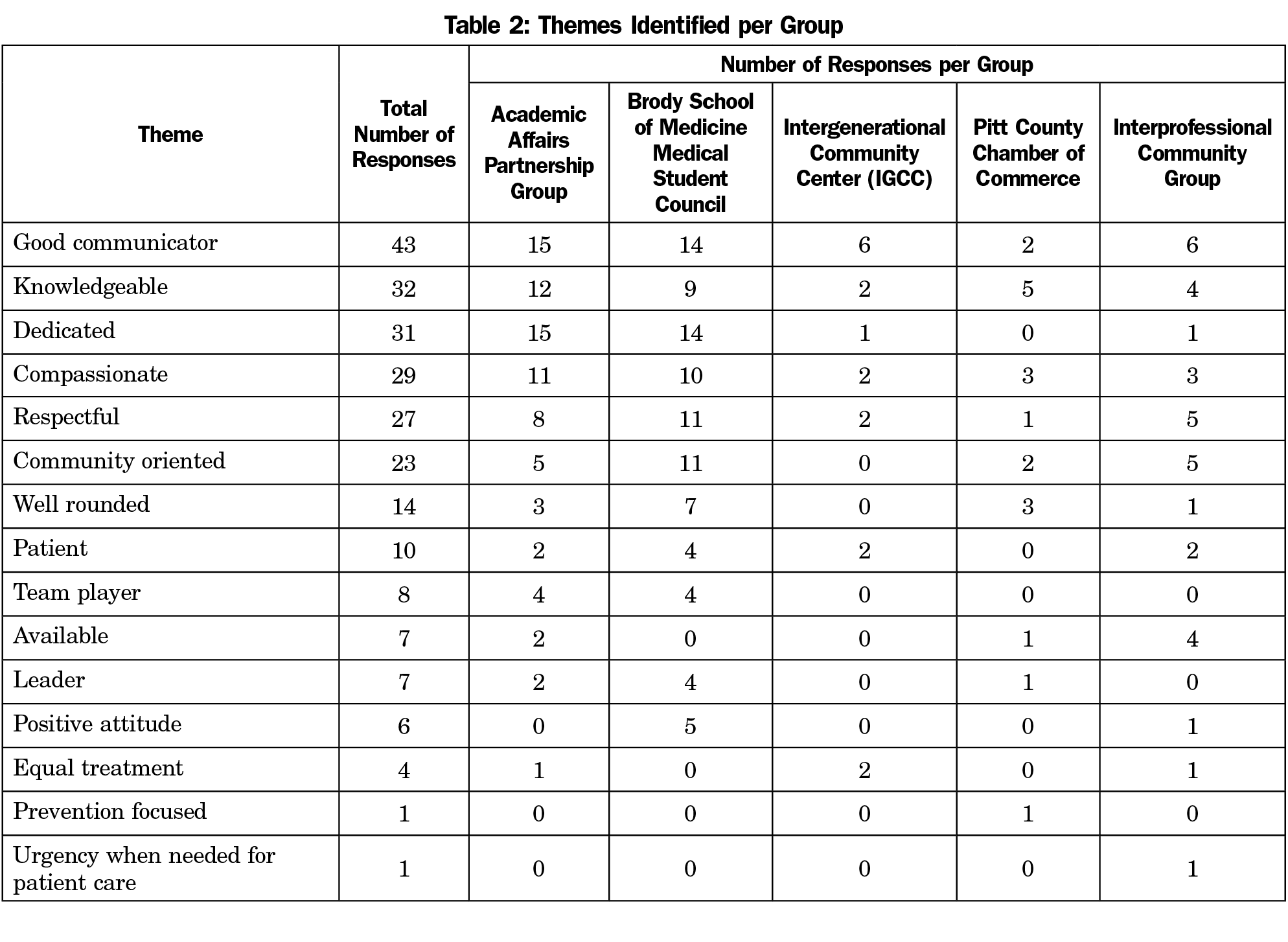

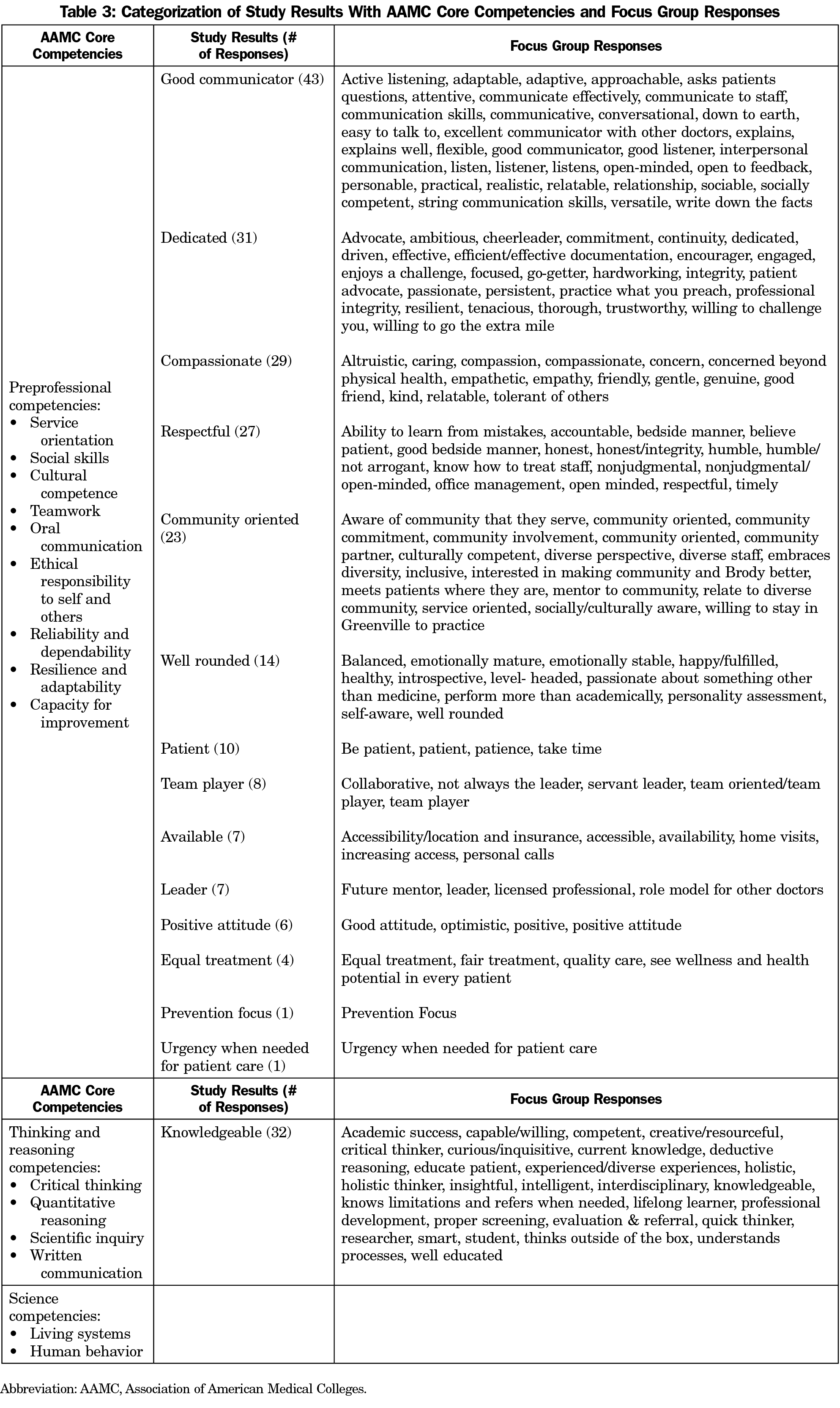

The total number of responses across groups was 243, representing 15 unique characteristics. The characteristics, as well as frequency counts for each term are shown in Table 2. Characteristics that were more commonly reported, which the authors defined as those with 20 or more comments, included good communicator (18%), knowledgeable (13%), dedicated (13%), compassionate (12%), respectful (11%), and community oriented (9%). Responses for these characteristics were 43, 32, 31, 29, 27, and 23 respectively (Table 3). The following top study responses aligned with stated AAMC competencies: good communicator with oral communication, knowledgeable with critical thinking, dedicated with ethical responsibility to self and others, compassionate with social skills and respectful with reliability and dependable.

The results of this study demonstrate characteristics a rural community and its medical school find as important traits of a physician. While study findings aligned with AAMC competencies in many ways, being community oriented was an additional competency that was identified. In rural areas, community orientation is important to prepare students for the leadership role they will assume in the community, and to help them understand the community’s health needs.16 In addition, introducing the medical school to the community can advance community goals, inform medical school initiatives, and impact health and academic outcomes.17,18 Results from this study, although from a single institution study with small discussion groups, suggest the importance of applicants to medical school being community oriented. This has special significance for rural, community-based medical schools with a goal to increase numbers of physicians going into primary care specialties.

Limitations of this study include a convenience sample of participants at a single institution, and use of a single prompt to capture responses. Also, confounders could be introduced because the participants were selected by the authors (K.M.C., K.L.) and Brody’s outreach director. However, prior research has suggested that unpacking the components of an agreed-upon composite goal (eg, “successful physician”) is an important precursor to optimizing medical school admission criteria and processes.19 Brody students possibly introduce bias as they are already rurally minded. The study would have been strengthened if discussion groups were held with students from other institutions and disciplines.

This study demonstrates characteristics that a rural community and its medical school consider when admitting applicants to their medical program. Further research should be done to determine if being community oriented should be a defined core competency for entering medical students.

References

- Patterson F, Knight A, Dowell J, Nicholson S, Cousans F, Cleland J. How effective are selection methods in medical education? A systematic review. Med Educ. 2016;50(1):36-60. doi:10.1111/medu.12817

- Association of American Medical Colleges. The Core Competencies for Entering Medical Students. https://students-residents.aamc.org/applying-medical-school/article/core-competencies/. Accessed September 8, 2019.

- Basco WT Jr, Buchbinder SB, Duggan AK, Wilson MH. Associations between primary care-oriented practices in medical school admission and the practice intentions of matriculants. Acad Med. 1998;73(11):1207-1210. doi:10.1097/00001888-199811000-00021

- Basco WT Jr, Gilbert GE, Blue AV. Determining the consequences for rural applicants when additional consideration is discontinued in a medical school admission process. Acad Med. 2002;77(10)(suppl):S20-S22. doi:10.1097/00001888-200210001-00007

- Raghavan M, Martin BD. Multiple mini interview performance of repeat applicants to medical school admission. Med J Aust. 2014;201(7):383-384. doi:10.5694/mja14.00728

- Spahr R. Family Medicine Leader: ECU’s Brody School of Medicine celebrated as national leader in family medicine. BusinessWire. https://www.businesswire.com/news/home/20181112005522/en/ECU%E2%80%99s-Brody-School-Medicine-Celebrated-National-Leader/?feedref=JjAwJuNHiystnCoBq_hl-RLXHJgazfQJNuOVHefdHP-D8R-QU5o2AvY8bhI9uvWSD8DYIYv4TIC1g1u0AKcacnnViVjtb72bOP4-4nHK5ieT3WxPE8m_kWI77F87Cse. Published November 12, 2018. Accessed July 15, 2020.

- Rabinowitz HK, Diamond JJ, Markham FW, Wortman JR. Medical school programs to increase the rural physician supply: a systematic review and projected impact of widespread replication. Acad Med. 2008;83(3):235-243. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318163789b

- Zink T, Center B, Finstad D, et al. Efforts to graduate more primary care physicians and physicians who will practice in rural areas: examining outcomes from the university of Minnesota-duluth and the rural physician associate program. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):599-604. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d2b537

- Wendling AL, Short A, Hetzel F, Phillips JP, Short W. Trends in subspecialization: a comparative analysis of rural and urban clinical education. Fam Med. 2020;52(5):332-338. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.182557

- Fuglestad A, Prunuske J, Regal R, Hunter C, Boulger J, Prunuske A. Rural family medicine outcomes at the University of Minnesota Medical School Duluth. Fam Med. 2017;49(5):388-393.

- Cathcart-Rake W, Robinson M, Paolo A. From infancy to adolescence: the Kansas University School of Medicine-Salina: a rural medical campus story. Acad Med. 2017;92(5):622-627. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001455

- Shipman SA, Wendling A, Jones KC, Kovar-Gough I, Orlowski JM, Phillips J. The decline in rural medical students: a growing gap in geographic diversity threatens the rural Physician Workforce. Health Aff (Millwood). 2019;38(12):2011-2018. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2019.00924

- Wendling AL, Shipman SA, Jones K, et al. Defining rural: the predictive value of medical school applicants' rural characteristics on intent to practice in a rural community. Acad Med. 2019;94(11S Association of American Medical Colleges Learn Serve Lead: Proceedings of the 58th Annual Research in Medical Education Sessions):S14-S20.

- Hsieh HF, Shannon SE. Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qual Health Res. 2005;15(9):1277-1288. doi:10.1177/1049732305276687

- Elo S, Kyngäs H. The qualitative content analysis process. J Adv Nurs. 2008;62(1):107-115. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2648.2007.04569.x

- Somporn P, Ash J, Walters L. Stakeholder views of rural community-based medical education: a narrative review of the international literature. Med Educ. 2018;52(8):791-802. doi:10.1111/medu.13580

- Campbell KM, Infante Linares JL, Tumin D, Faison K, Heath MN. The role of North Carolina medical schools in producing primary care physicians for the state. J Prim Care Community Health. 2020;11:2150132720924263. doi:10.1177/2150132720924263

- Campbell KM, Heath MN, Tumin D. Increasing the rural workforce of family medicine physicians: a community-focused approach. South Med J. 2020;113(4):148-149. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001080

- Kreiter CD, Axelson RD. A perspective on medical school admission research and practice over the last 25 years. Teach Learn Med. 2013;25(sup1)(suppl 1):S50-S56. doi:10.1080/10401334.2013.842910

There are no comments for this article.