Background and Objectives: Increasing human papillomavirus vaccination (HPVV) uptake is critical to the prevention of cervical cancer. Effective physician communication and clinical workflow policies have a significant impact on vaccination rates. However, resident training programs vary in the inclusion of training in effective HPVV practices. At Dell Medical School in Austin, Texas, HPVV rates at primary care residents’ clinic sites vary. We examined HPVV-related knowledge, training, barriers, and practices among residents in pediatrics (Peds), family medicine (FM), obstetrics and gynecology (Ob/Gyn), and internal medicine (IM) with the aim of identifying interventional targets to improve vaccination rates.

Methods: This was a mixed-method study including qualitative interviews and a survey. We interviewed a sample of residents from each specialty to assess their training experiences and how they discuss HPVV. We recorded, transcribed, and coded interviews for thematic analysis. All residents were offered the opportunity to complete an electronic survey to quantitatively evaluate knowledge and vaccine practices. We performed χ2 and Fisher exact analysis to compare results between disciplines.

Results: HPVV-related knowledge was similar across all four specialties and between resident year. Peds residents reported always recommending the HPVV significantly more than FM and Ob/Gyn residents for 11-17-year-old females. Only Peds residents reported receiving evidence-based vaccine communication training. Among all residents, the primary HPVV barriers included forgetting to offer the vaccine and time constraints. When discussing the vaccine, many interviewed residents were not offering a confident recommendation to all eligible patients, and instead were using a risk-based approach to vaccination.

Conclusions: There were inconsistencies across programs related to how and where residents receive HPVV training. This may impact the frequency and strength of resident vaccine recommendations. To increase HPVV rates, residency programs should prioritize implementation of multimodal interventions, including opt-out workflows and education on how to give confident vaccine recommendations.

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most common sexually transmitted infection in the United States and is a known cause of cervical, oropharyngeal, and other cancers.1-3 At the time of this study, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices (ACIP) recommended routine HPV vaccination (HPVV) at age 11 or 12 years, with catch-up vaccination up to ages 26 years for females and 21 for males.4 In June 2019, the ACIP endorsed HPVV in all individuals up to age 26 years and shared clinical decision-making for HPVV in unvaccinated adults up to age 45 years.5 While safe and efficacious, HPVV remains underutilized, creating a missed opportunity for cancer prevention.6

A strong physician recommendation is an important predictor of HPVV uptake.7-10 Despite this, half of physicians deliver low-quality recommendations lacking strong, timely, and consistent endorsement.11 This finding may be explained by resident physician training; a study of family medicine residency programs in Florida revealed that HPVV training is inconsistent and that instruction on how to offer high-quality recommendations is lacking.12 However, little is known about the level and impact of HPVV training in other primary care specialties tasked with giving HPVV.

At Dell Medical School in Austin, Texas, residents from different primary care disciplines train at separate federally-qualified health centers within the same network. HPVV initiation rates at clinics staffed by residents vary; at the pediatric clinic, for example, 91% of eligible 13-17-year-old patients received the first dose of the vaccine compared to 67% of patients at the family medicine clinic.13 Our study seeks to characterize HPVV-related knowledge, training, barriers, and practices among these residents in order to identify interventions to increase HPVV rates.

Pediatrics (Peds), family medicine (FM), obstetrics and gynecology (Ob/Gyn), and internal medicine (IM) residents were asked about their HPVV-related experiences through surveys and semistructured interviews. The UTHealth School of Public Health (Houston, TX) Institutional Review Board approved the study (IRB# HSC-SPH-18-0887).

Participants and Procedures

Residents were recruited to complete an electronic survey during didactic time and via email. Residents were also randomly selected to participate in phone interviews. Interviews with up to four residents from each specialty were conducted by two members of the research team.

Instruments

We adapted an online survey of 47 questions from instruments used in prior studies.8,14 We collected and stored data via REDCap, a secure platform for managing surveys.15 The interview guide consisted of 14 open-ended questions and was derived from a study of family medicine residents.12

Analysis

We performed χ2 with Yates correction and performed Fisher exact statistical analyses on HPVV survey knowledge and recommendation data among postgraduate year-1 (PGY-1) and upper-level residents and between Peds vs other specialties at the 5% significance level.16

We used qualitative content analysis to analyze interview transcripts.17 Initially, two team members independently reviewed a set of four deidentified interviews, one per specialty, and developed a set of codes and themes for each of the preidentified domains. We discussed differences and a final coding structure was agreed upon by both coders. We created a draft codebook, which was edited as new codes and themes emerged with review of additional transcripts. Code development focused on residents’ educational experiences, vaccine discussions in practice, and perceived barriers. We performed thematic analysis on all transcripts using a finalized codebook, and saturation was reached.

Survey Results

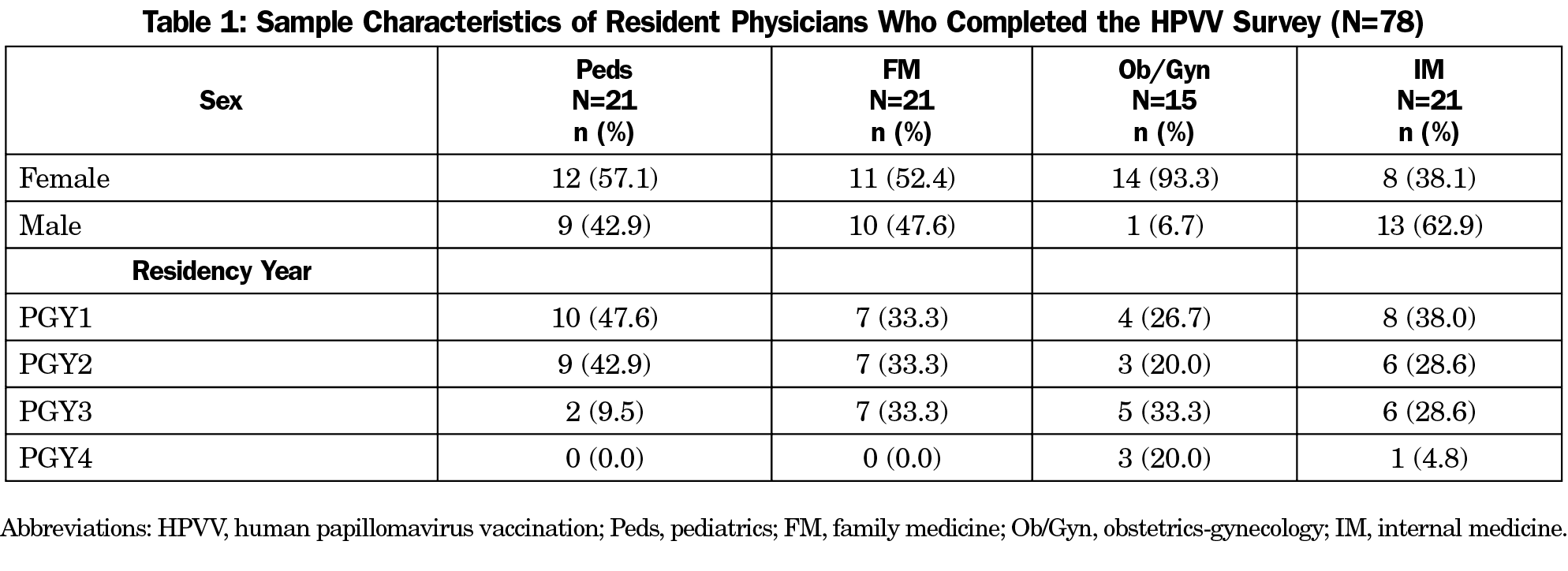

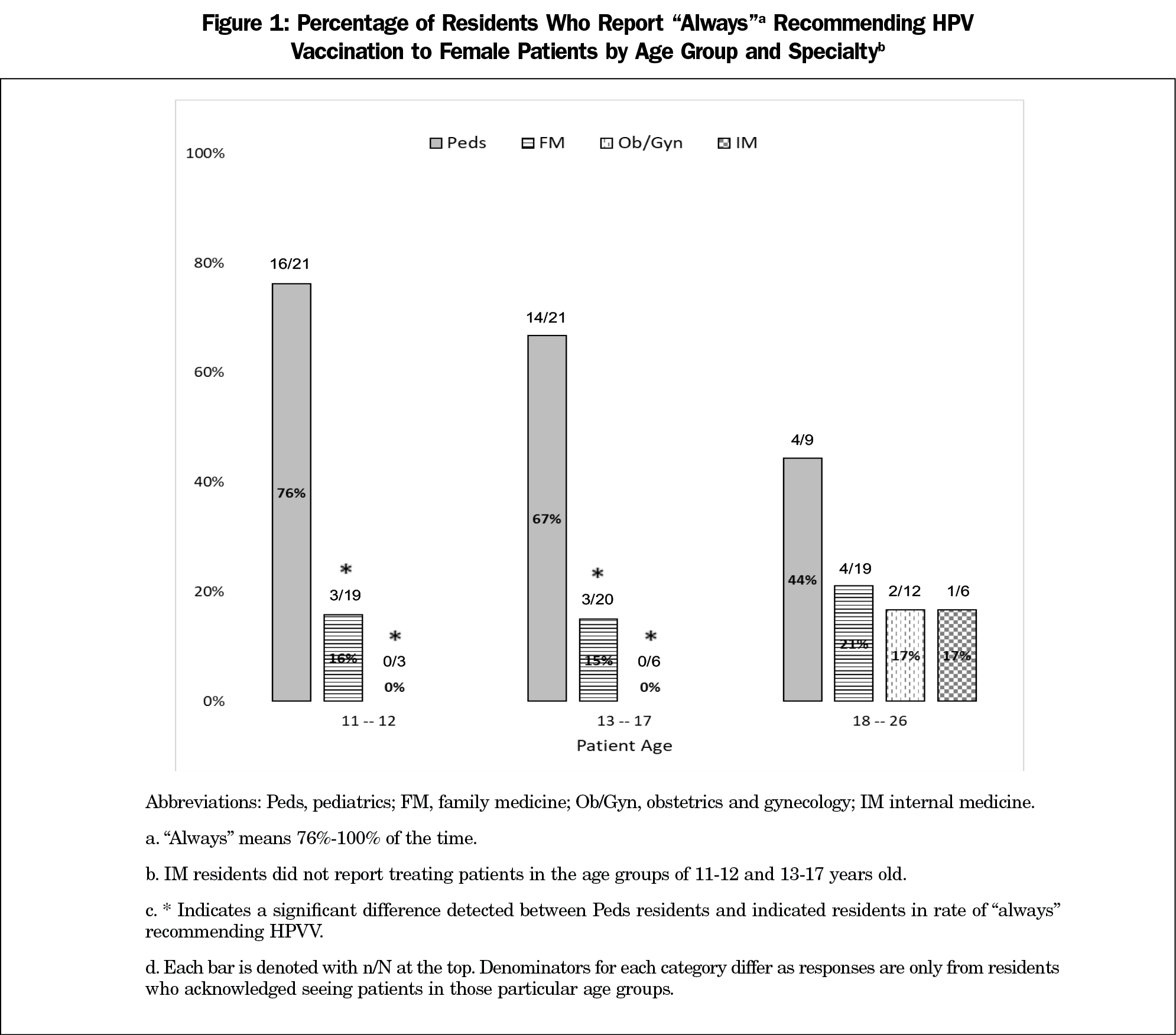

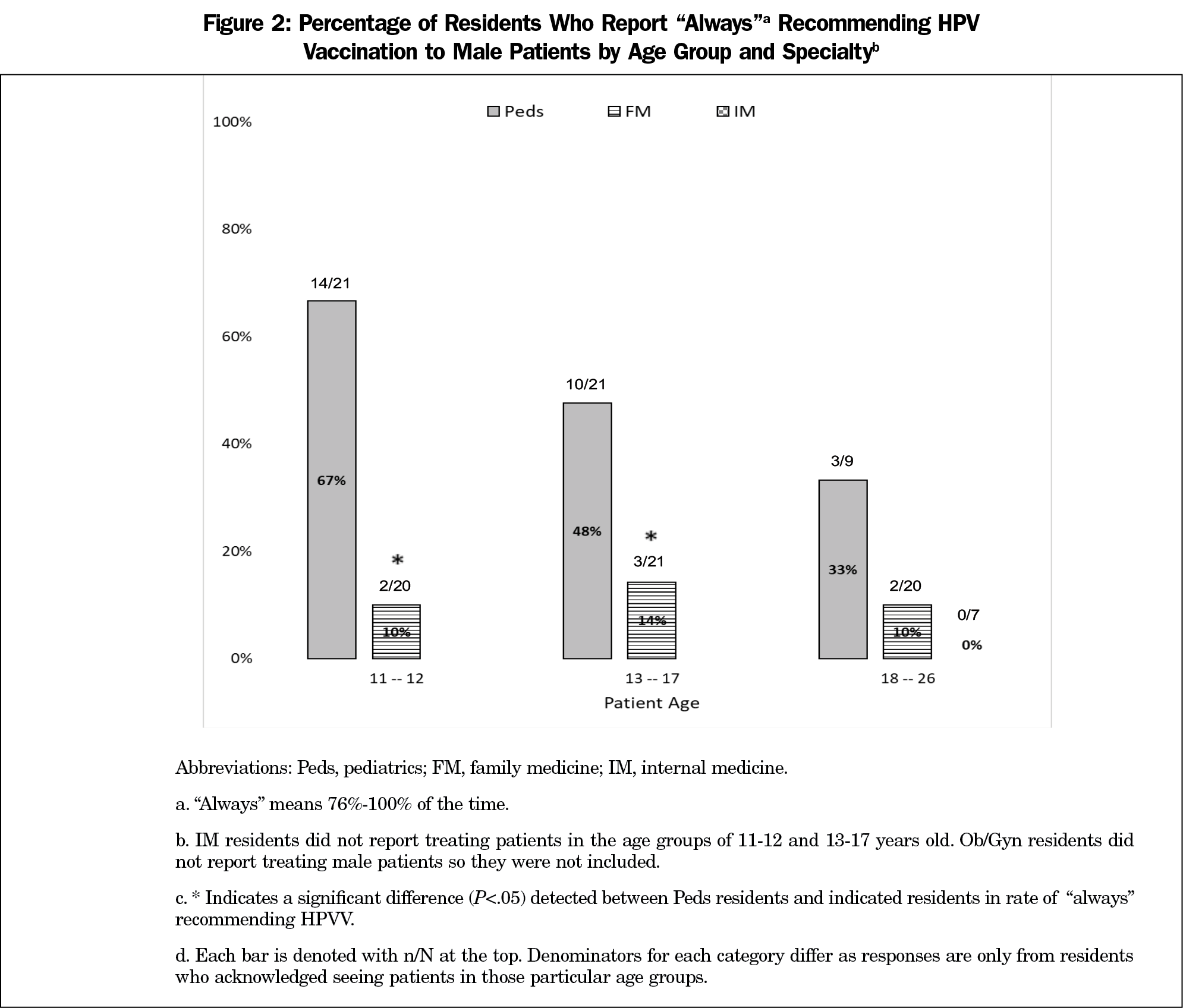

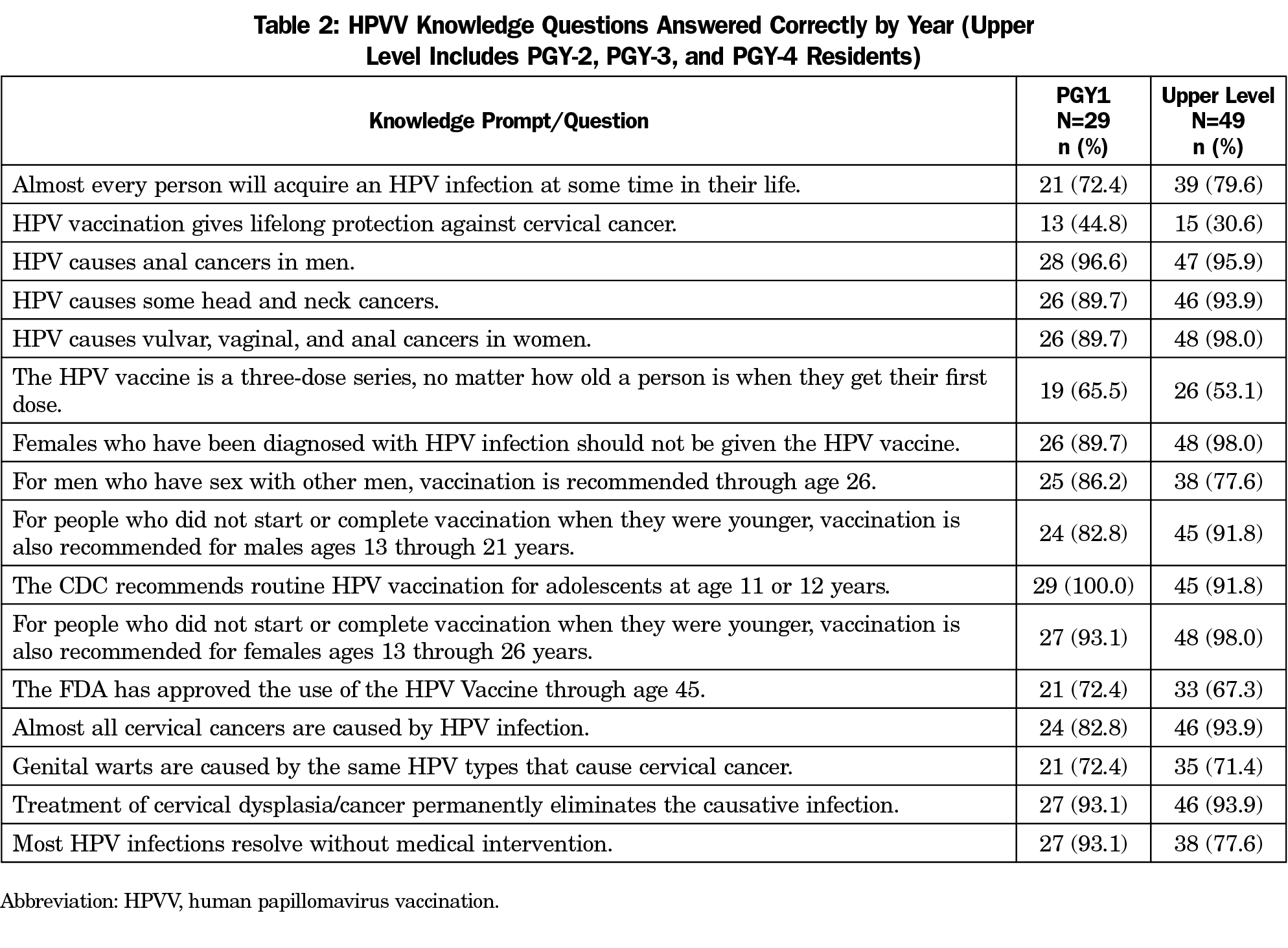

The resident survey response rate was 33% for Peds (21/63), 100% for FM (21/21), 75% for Ob/Gyn (15/20), and 36% for IM (21/59). Table 1 shows survey respondent characteristics. Peds residents more often reported always recommending HPVV, defined as offering the vaccine to patients at least 75% of the time (Figure 1). Peds residents were significantly more likely than OB residents to always recommend HPVV to females aged 11-17 years (Figure 1). Peds residents were also significantly more likely than FM residents to always recommend HPVV to females and males aged 11-17 years (Figures 1 and 2). Upper level residents were not significantly more likely to always recommend HPVV than PGY1s (P>.05). HPVV-related knowledge questions answered correctly ranged from 81%-85% and knowledge was not significantly different across specialties or between PGY-1 and upper-level residents (Table 2).

Thematic Analysis

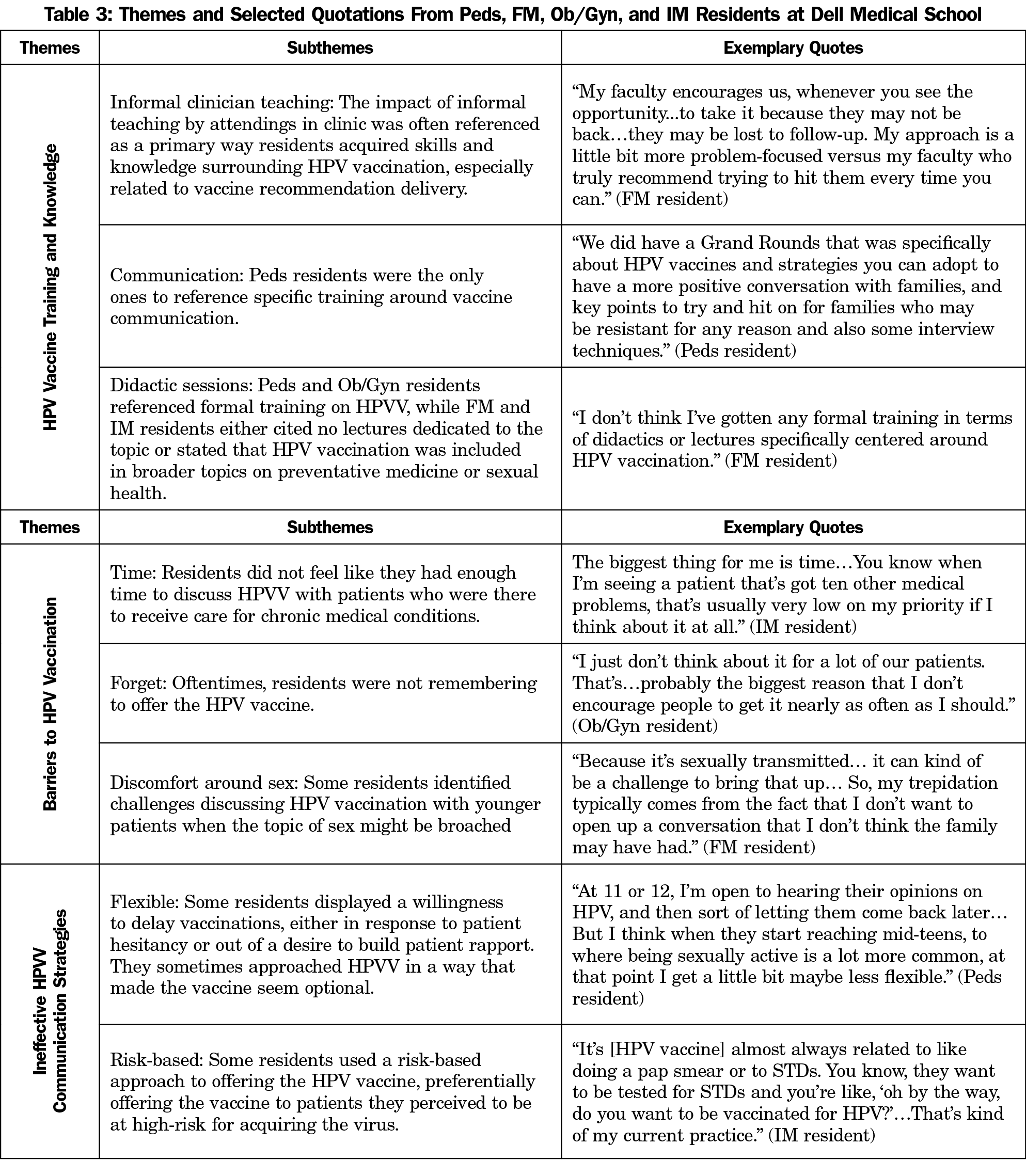

We conducted phone interviews with 14 residents, and these interviews were not connected to survey responses. We interviewed four Peds residents (50% male, 50% female; 25% PGY1, 75% upper level), four FM residents (75% male, 25% female; 25% PGY1, 75% upper level), two Ob/Gyn residents (100% female; 100% upper level), and four IM residents (50% male, 50% female; 25% PGY1, 75% upper level). Three main themes were identified: how residents receive HPVV training, perceived barriers to vaccination, and how residents communicate recommendations (Table 3).

Residents in all specialties cited modeling by attending physicians as an important way they learned about HPVV. Peds residents alone reported formal training on communication skills for recommending the vaccine.

Barriers to HPVV identified by residents across specialties included lack of time and forgetting to offer the vaccine. Some also identified challenges discussing HPVV with pediatric patients when the topic of sex might be broached.

Some residents indicated that they offer strong and consistent HPVV recommendations. Others introduced HPVV by gauging patient interest or reported using a risk-based approach to vaccination, preferentially offering HPVV to patients they perceived to be at high risk for virus acquisition.

Residents in our sample were not consistently recommending HPVV, despite having almost equal HPVV-related knowledge. As with previous studies, HPVV training was variable.12,18 Only the Peds residents referenced training on communicating vaccine recommendations, and this group offered HPVV at the highest rate.

When asked how they introduce HPVV, many reported strategies inconsistent with best practices.11 HPVV was often brought up as an option rather than a recommendation; this participatory approach offers patients more decision-making latitude.19 However, using an announcement or presumptive approach improves HPVV acceptance, as it assumes patients or parents are ready to vaccinate.19, 20

Some residents felt uncomfortable discussing HPVV with sexually-naïve pediatric patients and instead singled out patients who they believed were at higher risk for contracting HPV. A risk-based approach—which has historically been used by nearly 60% of physicians—is problematic, as it is difficult to accurately assess risk related to sexual behavior.11,21 Failing to universally vaccinate leads to inadequate protection against HPV for the population.

Forgetting to offer HPVV to eligible patients and lack of time were commonly cited barriers to vaccination. Physician prompts that improve vaccination rates include electronic health record alerts, verbal reminders from staff, and erasable signs on exam room doors used to indicate vaccines due that day.22,23 Additionally, in a previous study, physicians who received a 1-hour in-clinic HPVV recommendation training reported that the time it took to recommend the vaccine fell by 20%.24 Because time constraints are common for busy residents, communication training may boost vaccination rates.

Other clinic factors likely contribute to residents’ comfort with HPVV and clinic vaccination rates. Our own previous assessment at the Austin Peds and FM resident clinics revealed important differences in culture and workflow that may explain the significantly higher vaccination rates observed among Peds residents. For example, Peds residents benefit from chart preparation by nursing staff that flags when patients are due for HPVV, text message reminders to patients who are eligible for vaccination, and utilization of the state immunization registry. Primary care offices with higher HPVV rates report workflow ease surrounding HPVV including standing orders and chart preparation.25 Such practices at the Peds resident clinic undoubtedly contribute to a culture that promotes high rates of vaccination.

The study’s limitations included small sample sizes, low survey response rates, study at a single institution, and potential for selection bias, with only a 33% survey response rate among Peds residents. However, this study is novel in that it assesses the experiences of all primary care residents, not only Peds and FM residents, and points out the need for targeted training and changes in clinic culture to achieve high rates of HPVV among all disciplines.

HPVV is a critical cancer prevention strategy, and physicians must be empowered to offer it effectively to reduce the burden of HPV-related disease through increased HPVV administration. Clinics that implement strong HPVV recommendation education and adapt their workflow to promote vaccination may be ideal training centers for residents, regardless of specialty. Following the ACIP’s expansion of their HPVV guidelines, implementing such initiatives will be important for improving HPVV rates and saving adolescent and adult lives.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: This study was presented as a poster at the following events:

Dell Medical School Graduate Medical Education Research Day, May 10, 2019, Austin, TX.

Dell Medical School Innovation, Leadership and Discovery Scholarship Day, September 2019, Austin, TX.

References

- Chesson HW, Dunne EF, Hariri S, Markowitz LE. The estimated lifetime probability of acquiring human papillomavirus in the United States. Sex Transm Dis. 2014;41(11):660-664. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000193

- McQuillan G. Prevalence of HPV in adults aged 18–69: United States, 2011–2014. In: NCHS data brief, no 280. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics: 2017.

- Viens LJ, Henley SJ, Watson M, et al. Human papillomavirus-associated cancers - united states, 2008-2012. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2016;65(26):661-666. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6526a1

- Petrosky E, Bocchini JA, Hariri S, et al. Use of 9-Valent Human Papillomavirus (HPV) Vaccine: updated HPV vaccination recommendations of the Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices. In: MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. Vol 64.2015:300-304.

- Howard J. CDC panel recommends expanding ages for HPV vaccine. CNN Health. https://www.cnn.com/2019/06/26/health/hpv-vaccine-age-recommendations-acip-bn/index.html. Published June 27, 2019. Accessed July 4, 2019.

- Walker TY, Elam-Evans LD, Yankey D, et al. National, regional, state, and selected local area vaccination coverage among adolescents aged 13-17 years - United States, 2017. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2018;67(33):909-917. doi:10.15585/mmwr.mm6733a1

- Ylitalo KR, Lee H, Mehta NK. Health care provider recommendation, human papillomavirus vaccination, and race/ethnicity in the US National Immunization Survey. Am J Public Health. 2013;103(1):164-169. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2011.300600

- Vadaparampil ST, Kahn JA, Salmon D, et al. Missed clinical opportunities: provider recommendations for HPV vaccination for 11-12 year old girls are limited. Vaccine. 2011;29(47):8634-8641. doi:10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.09.006

- Dorell CG, Yankey D, Santibanez TA, Markowitz LE. Human papillomavirus vaccination series initiation and completion, 2008-2009. Pediatrics. 2011;128(5):830-839. doi:10.1542/peds.2011-0950

- Gilkey MB, Calo WA, Moss JL, Shah PD, Marciniak MW, Brewer NT. Provider communication and HPV vaccination: The impact of recommendation quality. 2016.

- Gilkey MB, Malo TL, Shah PD, Hall ME, Brewer NT. Quality of physician communication about human papillomavirus vaccine: findings from a national survey. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2015;24(11):1673-1679. doi:10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-15-0326

- Kasting ML, Scherr CL, Ali KN, et al. Human papillomavirus vaccination training experience among family medicine residents and faculty. Fam Med. 2017;49(9):714-722.

- CommUnityCare. HPV Initiation Summary 2018-2019. https://communitycaretx.org/. Accessed October 19, 2018.

- McSherry LA, O’Leary E, Dombrowski SU, et al; ATHENS (A Trial of HPV Education and Support) Group. Which primary care practitioners have poor human papillomavirus (HPV) knowledge? A step towards informing the development of professional education initiatives. PLoS One. 2018;13(12):e0208482. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0208482

- REDCap [software]. Nashville, TN: REDCap; 2020.

- Social Science Statistics. https://www.socscistatistics.com/. Accessed March 2020.

- Chapter 6: Qualitative Data Analysis. In: Tolley EE, Ulin PR, Mack N, Robinson ET, Succop SM. Qualitative Methods in Public Health: A Field Guide for Applied Research, Second Edition. San Francisco: John Wiley and Sons; 2016.

- Fox HB, McManus MA, Klein JD, et al. Adolescent medicine training in pediatric residency programs. Pediatrics. 2010;125(1):165-172. PubMed: 19969616. doi:10.1542/peds.2008-3740

- Opel DJ, Heritage J, Taylor JA, et al. The architecture of provider-parent vaccine discussions at health supervision visits. Pediatrics. 2013;132(6):1037-1046. doi:10.1542/peds.2013-2037

- Brewer NT, Hall ME, Malo TL, Gilkey MB, Quinn B, Lathren C. Announcements versus conversations to improve HPV vaccination coverage: a randomized trial. Pediatrics. 2017;139(1):e20161764. doi:10.1542/peds.2016-1764

- Schroder KE, Carey MP, Vanable PA. Methodological challenges in research on sexual risk behavior: II. Accuracy of self-reports. Ann Behav Med. 2003;26(2):104-123. doi:10.1207/S15324796ABM2602_03

- Rand CM, Schaffer SJ, Dhepyasuwan N, et al. Provider communication, prompts, and feedback to improve HPV vaccination rates in resident clinics. Pediatrics. 2018;141(4):e20170498. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-0498

- Ruffin MT IV, Plegue MA, Rockwell PG, Young AP, Patel DA, Yeazel MW. Impact of electronic health record (EHR) reminder on human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine initiation and timely completion. J Am Board Fam Med. 2015;28(3):324-333. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2015.03.140082

- Malo TL, Hall ME, Brewer NT, Lathren CR, Gilkey MB. Why is announcement training more effective than conversation training for introducing HPV vaccination? A theory-based investigation. Implement Sci. 2018;13(1):57. doi:10.1186/s13012-018-0743-8

- Lollier A, Rodriguez EM, Saad-Harfouche FG, Widman CA, Mahoney MC. HPV vaccination: pilot study assessing characteristics of high and low performing primary care offices. Prev Med Rep. 2018;10:157-161. doi:10.1016/j.pmedr.2018.03.002

There are no comments for this article.