Background and Objectives: The number of racially and culturally diverse patients in the medical practices of US physicians is increasing. It is unclear how well culturally and linguistically appropriate services (CLAS) standards have been integrated into physician practice. The objective of this study was to determine the prevalence of US-based physicians who received training in cultural competency and describe their behavior.

Methods: This survey study utilized data from a supplement of the 2016 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS). The NAMCS Supplement on CLAS for Office-based Physicians (National CLAS Physician Survey) is a nationally representative survey of ambulatory physicians. We determined the proportion and characteristics of physicians who reported receiving cultural competency training in medical school or in practice.

Results: The unweighted sample of 363 yielded a weighted sample of 290,109 physicians, 66.3% of whom reported that they had received cultural competence training at some point. Only 35.5% of the sample had ever heard of the CLAS standards, suggesting a low level of awareness of the standards. Further, only 18.7% reported that training in cultural competency is required for newly hired physicians who join their practice. There were no statistically significant differences between those who had been trained and those who had not in terms of self-reported consideration of race/ethnicity or culture in assessing patient needs, diagnosis, treatment and patient education (P>.05).

Conclusions: Fewer than half of practicing physicians reported receiving cultural and linguistic competency training in medical school or residency. It is possible that cultural competence training is being seamlessly integrated into medical education.

As the numbers of racial and culturally diverse patients increase in the medical practices of US physicians, the challenge of providing appropriate care founded upon a successful patient-physician relationship becomes more acute. The concept of cultural competency developed largely in response to the recognition that cultural and linguistic differences between health care providers and patients can affect communication and could affect the quality of health care delivery.1,2

The Institute of Medicine (IOM) report Unequal Treatment found that racial and ethnic disparities exist, and contributors to these disparities include interactions of health care providers, patients, and utilization managers.3 Cultural competency of providers helps to improve the patient-physician relationship and health outcomes.4,5 One of the IOM’s recommendations is that health care professionals receive training in cross-cultural communication or cultural competency to reduce racial and ethnic disparities. In 2000, the US Department for Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health (OMH) released the National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) in health care for adoption or adaptation by stakeholder organizations and agencies, and enhanced standards were released in 2013.6 The CLAS standards recognize that the provision of culturally competent health services is fundamental for the quality of care and aims to reduce disparities. In 2000, the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) added a standard for medical school education programs to include cultural competency education within their curricula.7 This is also a priority in graduate medical education.8

It is currently unclear how much the CLAS standards and culturally competent behavior has been integrated into physician practice. Moreover, there is a gap in our understanding of the types of strategies that practicing physicians integrate into practice. Given the growing recognition of the importance of culturally competent care, it is vital to determine the prevalence of US-based physicians who received training in cultural competence and differences in their behavior with physicians who have not received training. Consistent with this gap in the literature, we analyzed a nationally representative survey of ambulatory physicians regarding the CLAS standards, their reports of training in cultural competence, and reports of provision of cultural and linguistically appropriate care.

This study utilized data from the 2016 National Ambulatory Medical Care Survey (NAMCS), the most current national data on office practice. The NAMCS is a national probability sample survey that samples ambulatory medical care visits to office-based physicians, and can be used to make national estimates regarding ambulatory medical care in the United States.9 The current study focuses on the data collected in the Supplement on Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services for Office-based Physicians (National CLAS Physician Survey). The 2016 National CLAS Physician Survey followed a similar sample design and eligibility rules as the 2015 NAMCS.10 The basic sampling unit for the National CLAS Physician Survey is the physician. The sampling frame for the National CLAS Physician Survey included nonfederally employed physicians classified by the American Medical Association (AMA) or the American Osteopathic Association (AOA) as “office-based, patient care” and physicians classified as hospital-employed by the AMA.

The University of Florida Institutional Review Board approved this study as execmpt because it uses deidentified public use data.

Training in Cultural Competency

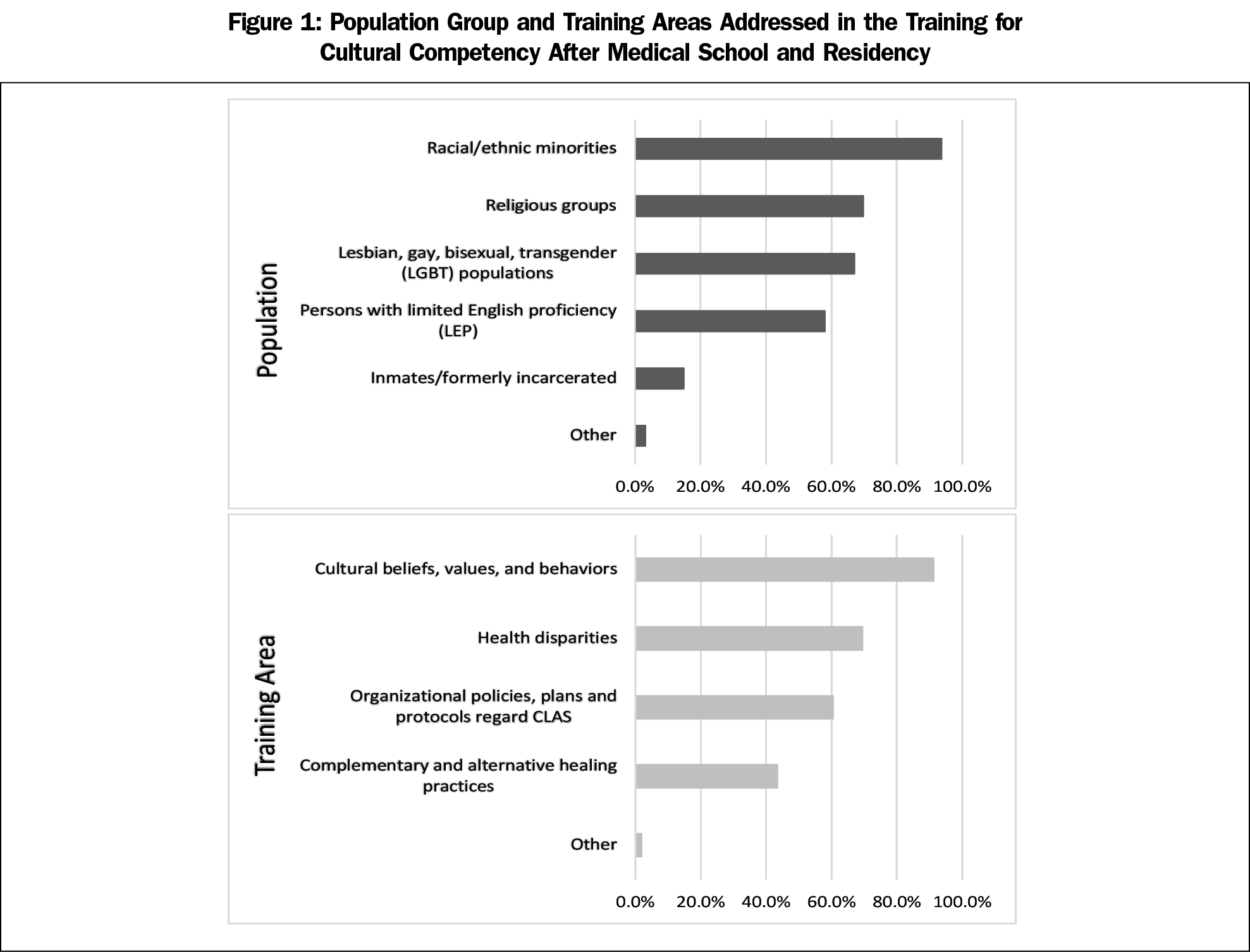

Respondents were asked if they had received training in cultural competency at three different time points: (1) during their medical school/residency, (2) after medical school/residency, and (3) within the past 12 months. If they had received training postresidency they were asked if the training addressed different population groups including racial/ethnic minorities; religious groups; lesbian, gay, bisexual and transgender (LGBT); persons with limited English proficiency; and inmates/formerly incarcerated. They were also asked if the following areas were included in the cultural competency trainings: cultural beliefs, values, and behaviors; organizational policies; health disparities; and complementary and alternative healing practices. Finally, they were asked if the cultural competency training was used to satisfy a continuing medical education requirement or as a requirement for credentialing.

We operationalized a physician receiving training in cultural competency as someone who answered affirmatively to either the question asking about training in medical school or residency or training post medical school or residency.

The respondents were then asked about cultural competency training in their practice. They were asked if cultural competency training is required for newly hired physicians in the practice and how often the practice offers cultural competency training (eg, annually, biannually).

Consideration of Cultural Issues in Providing Care by the Physician and the Practice

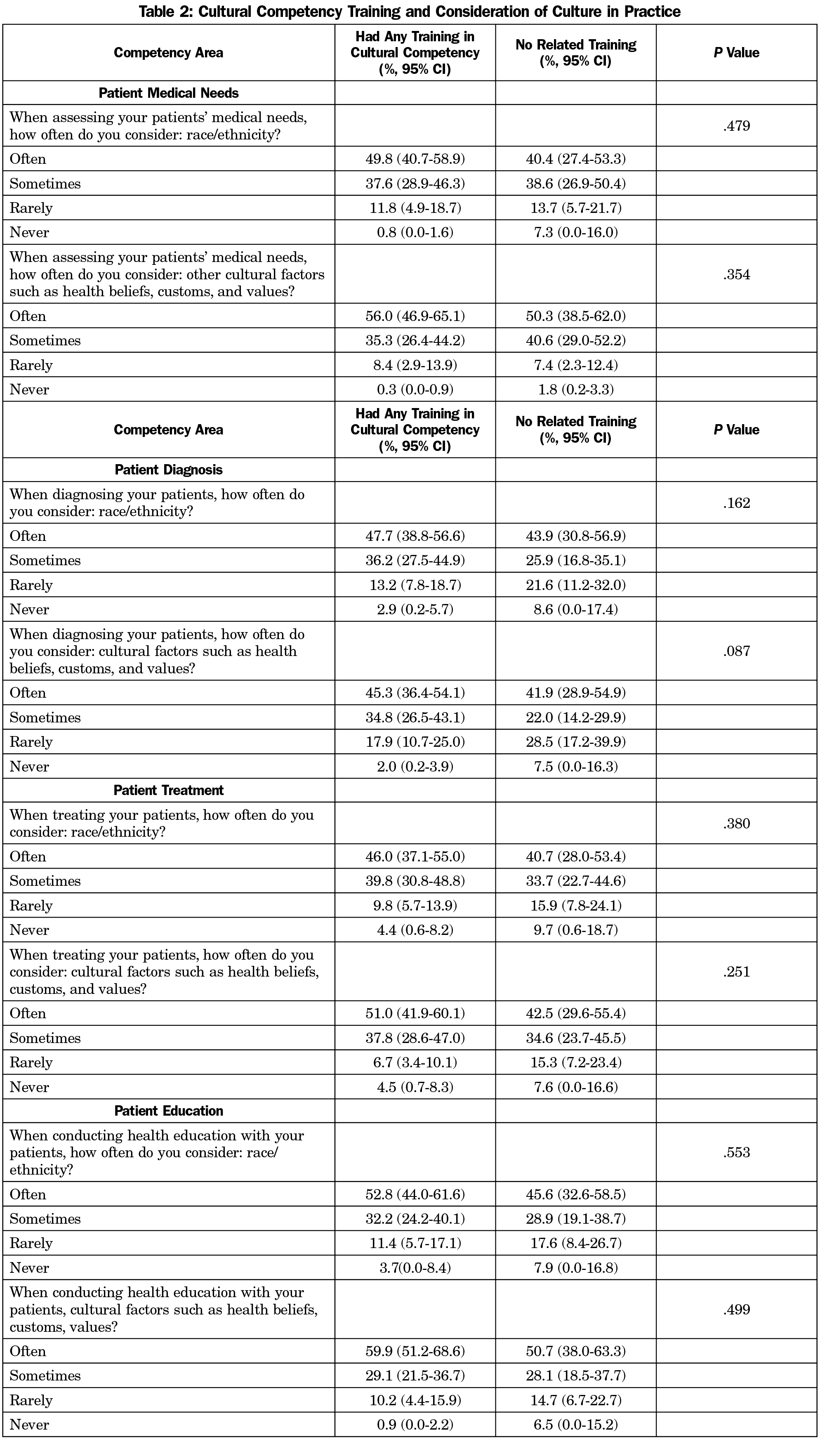

The respondents were asked to evaluate four different issues in their personal delivery of health care in terms of frequency of consideration (often, sometimes, rarely, never) of race/ethnicity and other cultural factors (eg, health beliefs, customs, values). The health care issues were: (a) assessing your patients’ medical needs, (b) diagnosing your patient, (c) treating your patients, and (d) conducting health education with your patients.

The participating physicians were asked how often their practice assesses their services to patients for their cultural and linguistic appropriateness. Additionally, the respondents were asked in terms of the practice what characteristics of their patients’ culture and language characteristics are recorded including nationality, patient’s primary language, sexual orientation/gender identity, religion, and income. Finally, the respondents were asked if they were familiar with the National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) in Health and Health Care. For those who had heard of the standards, the respondent was asked if the practice had adopted the CLAS standards.

Perception of the Impact of Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services

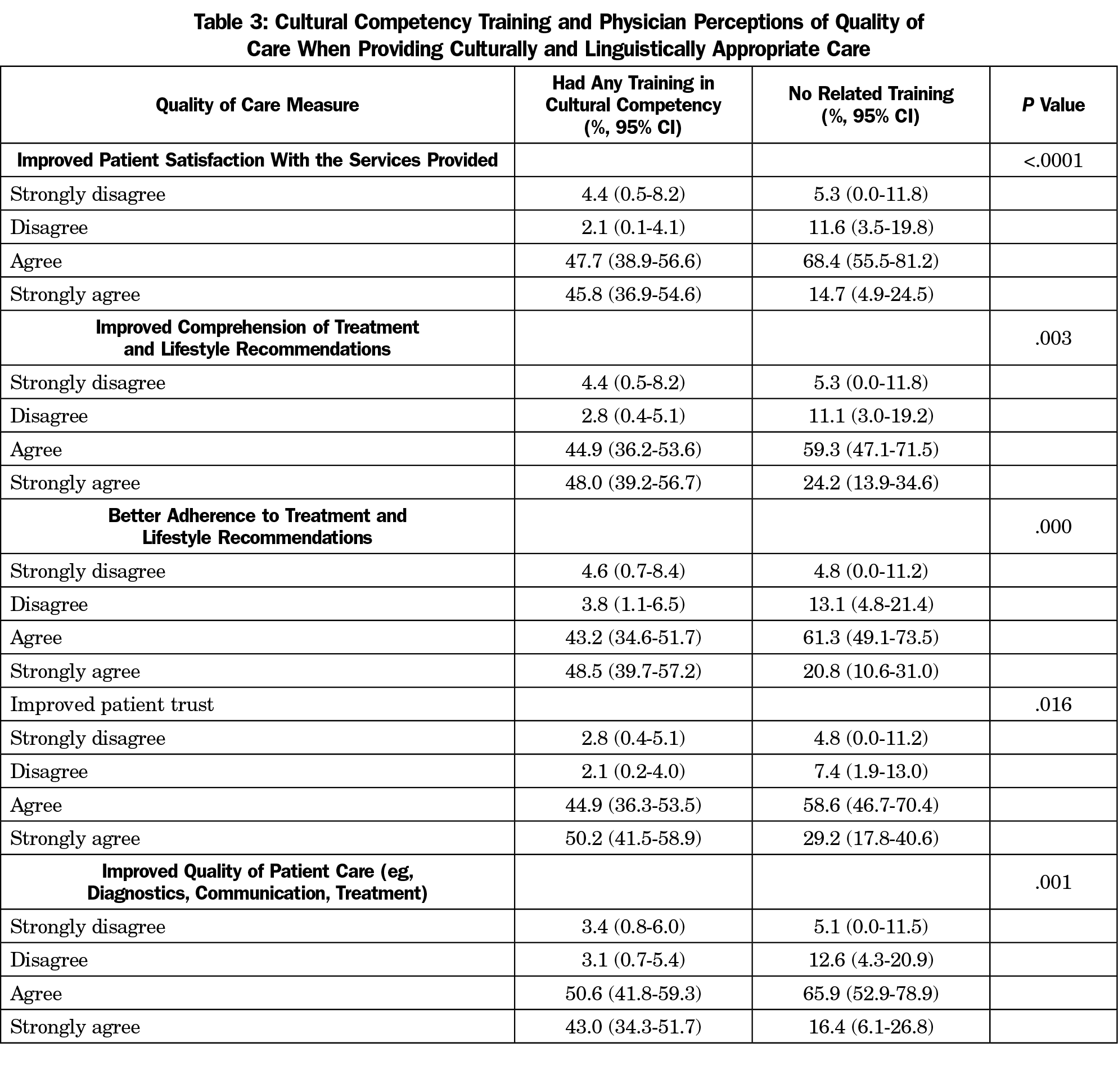

The NAMCS CLAS survey included six items focused on the perception of impact of providing culturally and linguistically appropriate services to patients. These items were assessed in terms of agreement (strongly disagree, disagree, agree, strongly agree). The stem was “By providing culturally and linguistically appropriate services to my patients I expect:” The agreement items focused on (a) improved patient satisfaction, (b) improved comprehension of treatment and lifestyle recommendations, (c) better adherence to treatment and lifestyle recommendations, (d) improved patient trust, (e) improved quality of patient care, and (f) decreased likelihood of liability/malpractice claims.

Respondent Characteristics

Physician characteristics, including specialty, type of practice setting, ethnic composition of practice, sex, and physician race/ethnicity were assessed in the survey and used in the analysis.

Analysis

The data provide nationally representative estimates for physician behavior and experiences. To account for the complex sampling design of the NAMCS, we used SAS 9.4 (Cary, NC) survey procedures for all analysis. The analysis included a physician weighting variable as well as variables provided in NAMCS that account for stratum level differences and primary sampling unit differences for all analyses. We conducted χ2 tests for relationships focusing on the association between cultural competence training and both physician behaviors and perceived patient outcomes.

The unweighted sample comprised 393 physicians representing a nationally representative weighted sample of 290,109 physicians. Regarding reports of receiving training in cultural competence, 47.9% received training in medical school or residency and 47.9% received training postresidency. Overall, 66.3% of the respondents reported receiving cultural competence training at some point. Among those who have had training once entering medical practice, when asked whether they have participated in any training for cultural competency within the past 12 months, only 34.5% had done so. For the overall population of physicians in the study, only 35.5% had ever heard of the CLAS standards. Among individuals who reported receiving some cultural competence training, 57.7% reported that they had never heard of the CLAS standards. Among those who had not received training, 77.7% had never heard of the CLAS standards, suggesting a low level of awareness of the standards.

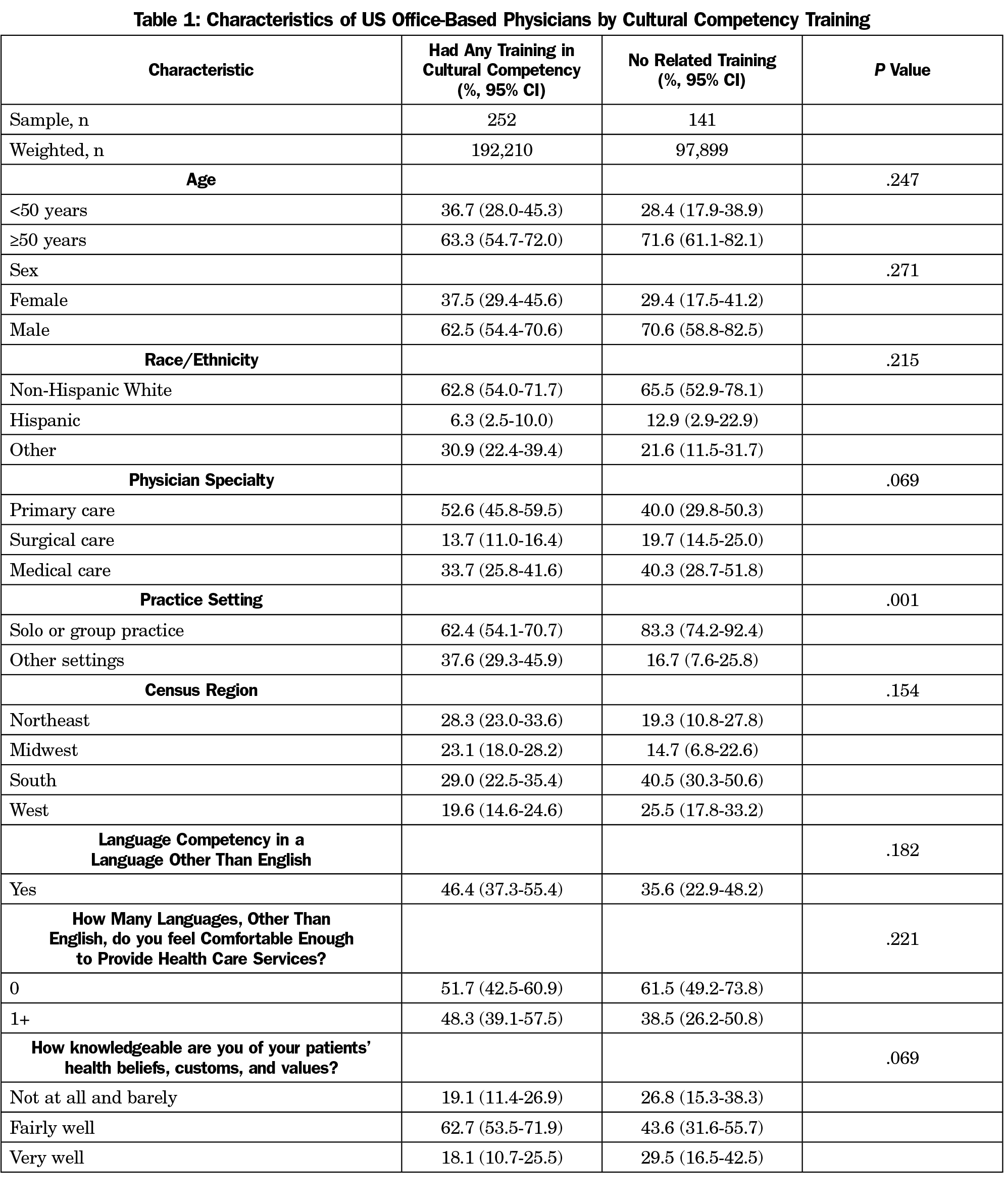

Table 1 shows the characteristics of physicians who reported that they have ever received some sort of cultural competence training and those who said that they have not. Those who reported receiving training were not statistically significantly different from those who did not report receiving training on demographic and practice characteristics, except in terms of practice size. In terms of a self-assessment of how knowledgeable the physician is about the patients’ health beliefs, customs and values, more than 70% of both groups felt fairly or very knowledgeable. Figure 1 shows the types of training and the groups highlighted in the training that occurred after medical school or residency. The most common groups discussed were racial and ethnic minorities and the most common topical focus was on culture, health beliefs and behavior. Further, only 18.7% reported that training in cultural competency is required for newly hired physicians who join their practice and only 31.5% reported that such training is offered in their practice.

The results shown in Table 2 demonstrate the differences in how physicians who reported receiving cultural competence training and those who did not report receiving training interact with their patients around cultural and interpersonal issues. There were no statistically significant differences between those who had received training and those who had not. In contrast to the results on reported behaviors with patients, Table 3 demonstrates the agreement of the perceived impact of providing culturally and linguistically appropriate health services on interpersonal quality of care. The respondents who reported cultural competence training were significantly more likely to agree with statements suggesting a positive impact on quality of care compared to those who did not report receiving cultural competence training.

The results of this nationally representative survey of physicians indicates that fewer than half of practicing physicians reported receiving cultural and linguistic competency training in medical school or residency, and only 66% reported receiving them either in training or posttraining. Moreover, only 35% of the respondents had heard of the CLAS standards and only 19% of respondents said that their practice requires cultural competency training for new hires. This practice of requiring culturally competent training in the workplace is likely to be more prevalent for individuals with hospital privileges than for those only doing ambulatory care. This suggests that even though the Institute of Medicine and the US Department for Health and Human Services Office of Minority Health have emphasized the need for culturally competent care and training, training uptake could be improved.

It appears that physicians perceive themselves providing culturally competent care regardless of whether they recalled having specific training. There were no significant differences between the groups on their self-perceptions of behavior or their knowledge of the patient. Both groups report behaviors dealing with patients consistent with accounting for their patients’ culture, language, and health beliefs (eg, consideration of culture or ethnicity for diagnosis or treatment). They also consider themselves to be knowledgeable of their patients’ health beliefs, customs and values. One place where the two groups differed was in the perceived importance of culturally competent care on their patients’ quality of care. Those who received training perceived greater impact of culturally competent care on their patients’ quality of care than those who did not. The perception of the importance of providing culturally competent care could relate to physician training to provide culturally competent care, and within that context, physicians may have learned of the evidence of the impact of culturally competent care. Since both groups of physicians report providing culturally competent care these perceptions of the impact of culturally competent care may be an artifact of training.

There was no difference in the likelihood of having participated in cultural competence training by the age of the physician. Brottman et al describe the various types of educational activities reported in the literature regarding health professions training in cultural competency.2 The CLAS standards were released in 2000, and in 2000 the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) added a standard that medical schools must include cultural competence education for students. It is possible that some respondents who graduated since that period may not recall or recognize those elements within their medical school education or even other training as a formal cultural competence training. A recent scoping review of cultural competency interventions during medical school showed a wide variety of interventions and strategies to integrate cultural competence training into the curriculum.11 That may help to account for why there were no significant differences between those who reported formal training and those who didn’t in their behaviors toward patients in terms of accounting for race/ethnicity and cultural factors. Along those same lines, family medicine training in the biopsychosocial model requires being knowledgeable about health, beliefs, and values and how that integrates into care. Although not directly labelled cultural competency training, this type of training may still yield culturally competent physicians.

This study has several limitations. First, both physicians who reported receiving cultural competency training and those who didn’t receive the training, believe that they are providing culturally and linguistically appropriate services. A trusting patient physician relationship is based on perceptions involved in the interactions that are influenced by shared understanding of language, beliefs, and customs. The study is not able to examine whether patient outcomes are different between those who received training and those who did not. The study did not examine if patients perceived themselves to have received culturally competent care from the physicians. Studies have indicated that physicians often perceive themselves as more culturally competent than do their patients.12 Second, the cultural competency training assessed in this study is based on physician self-report. This could be affected by recall bias. The actual experience and training curriculum for each respondent is unstandardized. The types of training and the groups to which they relate were assessed providing an idea of the curricula. Moreover, there may be some social desirability in the responses. Further, the overt or formal dissemination and labelling of the CLAS standards may not be revealed to the individuals receiving the training. Despite these limitations, this is the first nationally representative study of practicing physicians to examine the provision of culturally and linguistically appropriate services/training.

In conclusion, the vast majority of physicians, regardless of reported formal training, believe that they are knowledgeable of their patients’ health beliefs, customs, and values and consider those issues in all aspects of providing health care to the patients. Only two-thirds of this nationally representative study of physicians reported formal training in cultural competence and only 35% had heard of the CLAS standards, so it is possible that cultural competence training is being seamlessly integrated into medical education. Future research needs to examine the patient-reported outcomes of physicians reporting no formal training, yet perceive themselves providing culturally competent care.

References

- Truong M, Paradies Y, Priest N. Interventions to improve cultural competency in healthcare: a systematic review of reviews. BMC Health Serv Res. 2014;14(1):99. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-14-99

- Brottman MR, Char DM, Hattori RA, Heeb R, Taff SD. Toward Cultural Competency in Health Care: A Scoping Review of the Diversity and Inclusion Education Literature. Acad Med. 2020;95(5):803-813. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002995

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Understanding and Eliminating Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Unequal treatment: confronting racial and ethnic disparities in health care. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/25032386. Published 2003. Accessed November 12, 2019.

- Seay J, Hicks A, Markham MJ, et al. Developing a web-based LGBT cultural competency training for oncologists: the COLORS training. Patient Educ Couns. 2019;102(5):984-989. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2019.01.006

- Carpenter R, Estrada CA, Medrano M, Smith A, Massie FS Jr. A web-based cultural competency training for medical students: a randomized trial. Am J Med Sci. 2015;349(5):442-446. doi:10.1097/MAJ.0000000000000351

- National Standards for Culturally and Linguistically Appropriate Services (CLAS) in Health and Health Care. Federal Register. https://www.federalregister.gov/documents/2013/09/24/2013-23164/national-standards-for-culturally-and-linguistically-appropriate-services-clas-in-health-and-health. Published September 24, 2013. Accessed November 12, 2019.

- Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC). Cultural competence education. https://www.aamc.org/system/files/c/2/54338-culturalcomped.pdf. Accessed November 12, 2019.

- Ambrose AJ, Lin SY, Chun MB. Cultural competency training requirements in graduate medical education. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(2):227-231. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-12-00085.1

- National Center for Health Statistics. About the Ambulatory Health Care Surveys. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/about_ahcd.htm. Published September 6, 2019. Accessed November 12, 2019.

- National Center for Health Statistics. Questionnaires, Datasets, and Related Documentation. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/ahcd/ahcd_questionnaires.htm. Published August 31, 2017. Accessed November 12, 2019.

- Deliz JR, Fears FF, Jones KE, Tobat J, Char D, Ross WR. Cultural Competency Interventions During Medical School: a Scoping Review and Narrative Synthesis. J Gen Intern Med. 2020;35(2):568-577. doi:10.1007/s11606-019-05417-5

- Ohana S, Mash R. Physician and patient perceptions of cultural competency and medical compliance. [published correction appears in Health Educ Res. 2016 Feb;31(1):107]. Health Educ Res. 2015;30(6):923-934. doi:10.1093/her/cyv060

There are no comments for this article.