Background and Objectives: Medical student distress and mental health needs are critical issues in undergraduate medical education. The imposter phenomenon (IP), defined as inappropriate feelings of inadequacy among high achievers is linked to psychological distress. We investigated the prevalence of IP among first-year medical school students and its association with personality measures that affect interpersonal relationships and well-being.

Methods: Two hundred fifty-seven students at a large, urban, northeastern medical school completed the Clance Impostor Phenomenon Scale (CIPS), Jefferson Scale of Empathy, Self-Compassion Scale, and Zuckerman-Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire immediately before beginning their first year of medical school. At the end of their first year, 182 of these students again completed the CIPS.

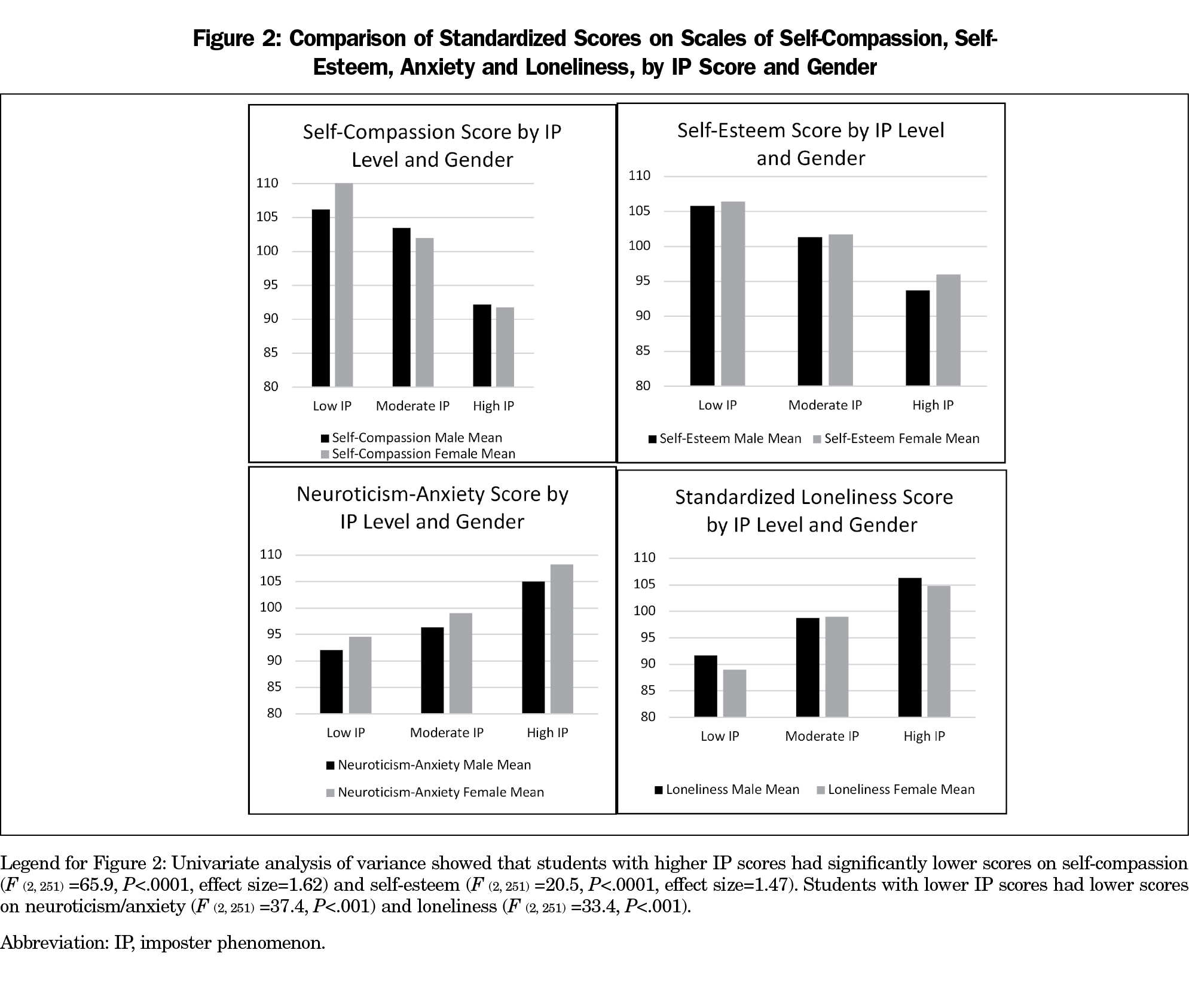

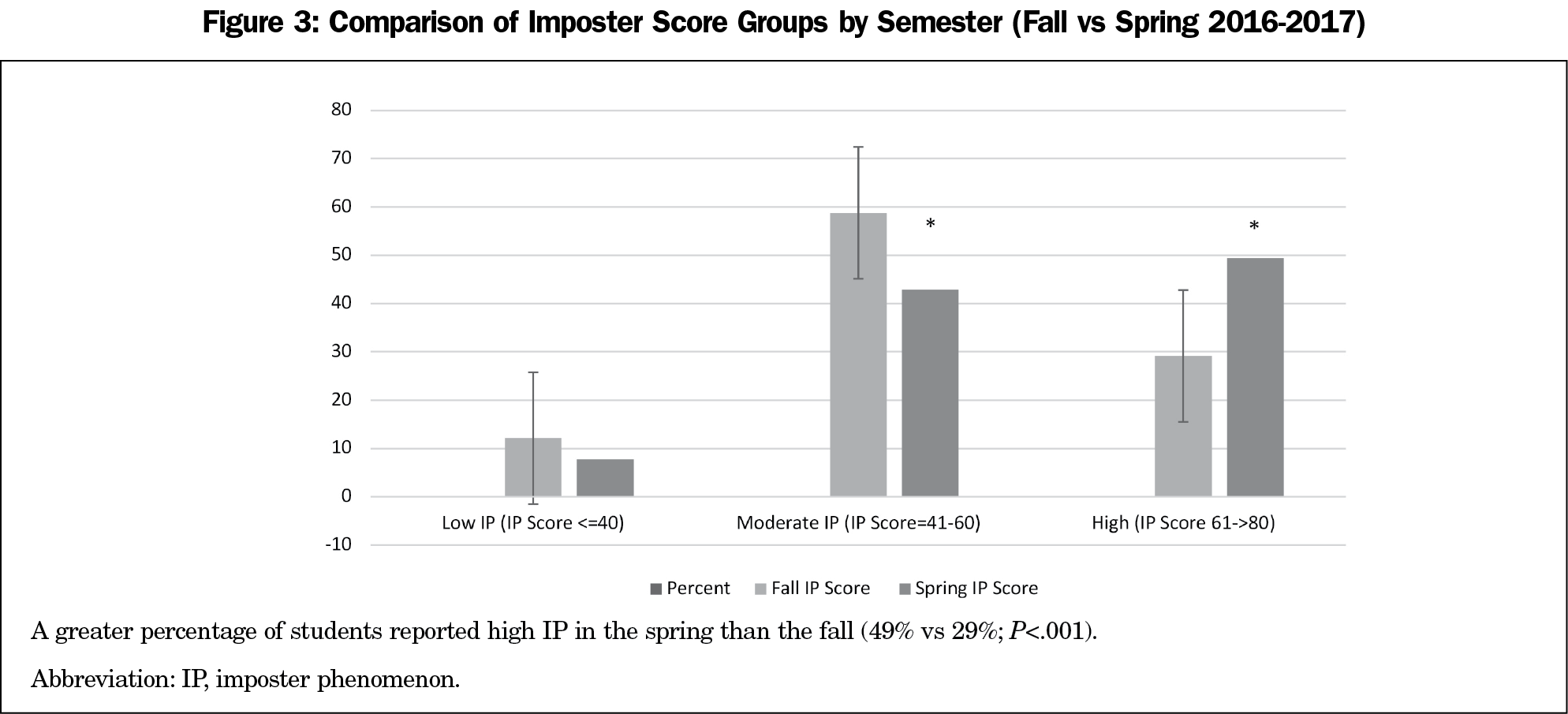

Results: Eighty-seven percent of the entering students reported high or very high degrees of IP. Students with higher IP scores had significantly lower mean scores on self-compassion, sociability self-esteem (P<.0001 for all), and getting along with peers (P=.03). Lower IP scores were related to lower mean scores on neuroticism/anxiety and loneliness (P<.001 for both). Women obtained a higher mean IP score than men. IP scores at the end of the school year increased significantly compared with the beginning of the year (P<.001), both in frequency and intensity of IP.

Conclusions: IP was common in matriculating first-year medical students and significantly increased at year’s end. Higher IP scores were significantly associated with lower scores for self-compassion, sociability, self-esteem, and higher scores on neuroticism/anxiety.

Alarming rates of depression, anxiety, and burnout are reported among medical students.1-4 Identifying and intervening to support psychological well-being in these learners is a continuing challenge. One personality construct, the imposter phenomenon (IP), is associated with emotional distress in some high-achieving individuals who are unable to internalize their achievements or take ownership of their success.5-7 IP has been described widely in the lay-press,8 social media,9 and college publications,10 but rarely explored in the medical literature. This mindset of self-perceived fraudulence was described by Clance and Imes in 1978 in female academicians11 and is associated with personality traits including depression, anxiety, neuroticism, low self-esteem, maladaptive perfectionism, increased work-related stress, underperformance, self-sabotage, and diminished career development.5-8 The well-validated Clance Imposter Phenomenon Scale (CIPS) is used to determine the presence and severity of IP.11,12 Rates of IP during training in health care professionals were reported in one study as 30% for medical, dental, and pharmacy students.13 In a study of medical students, 50% of female and 25% of male students demonstrated significant imposterism.15 Recently, a small study found that 54% of entering medical students exhibited scores above the cutoff for imposterism, which significantly increased at the end of the M-3 year and remained unchanged at the end of the M-4 year.16 Studies in graduate medical education show similar results. A study of Canadian family medicine residents found IP in 41% of women and 24% of men.17 In an internal medicine program, 86% of foreign medical graduates exhibited IP compared with 36% of Canadian medical school graduates.18 A report of US surgical residents and attending physicians found that both exhibited high IP with no gender differences or decrease in IP during training.19 A qualitative interview-based study of 28 Canadian physicians also found that imposter feelings, self-doubt, and fraudulence were common and persistent.20

The presence of IP in prematriculants to medical school and persistence or changes in these feelings at the end of the first year have not been previously studied. Given the intense pressure and competition faced by undergraduates for medical school admission, as well as the stressors well known to occur in the preclinical years of medical school,14 we hypothesized that IP would be present in prematriculating students and would increase by the end of that year. We were also interested in exploring which personality traits were related to imposterism in our students.

Participants and Procedures

Participants were students enrolled in a large urban Pennsylvania medical school class of 2020. We collected data by electronic survey during the month preceding their first year of matriculation (fall 2016) and at the end of the first year (spring 2017) as part of the Jefferson Longitudinal Study of Medical Education.21 We connected scores between the pre- and postsurvey by a key numeric variable. The university’s committee on human subjects’ protection approved the study.

Instruments

Impostor Phenomenon. We used Clance’s IP scale, a 20-item validated instrument developed to measure IP.11,12 A sample item is: “Sometimes I’m afraid others will discover how much knowledge or ability I really lack.” To examine the incidence and degree of IP we administered the CIPS at the beginning and conclusion of the M-1 year. In addition, we assessed the relationship of IP to personality measures impacting psychological well-being.

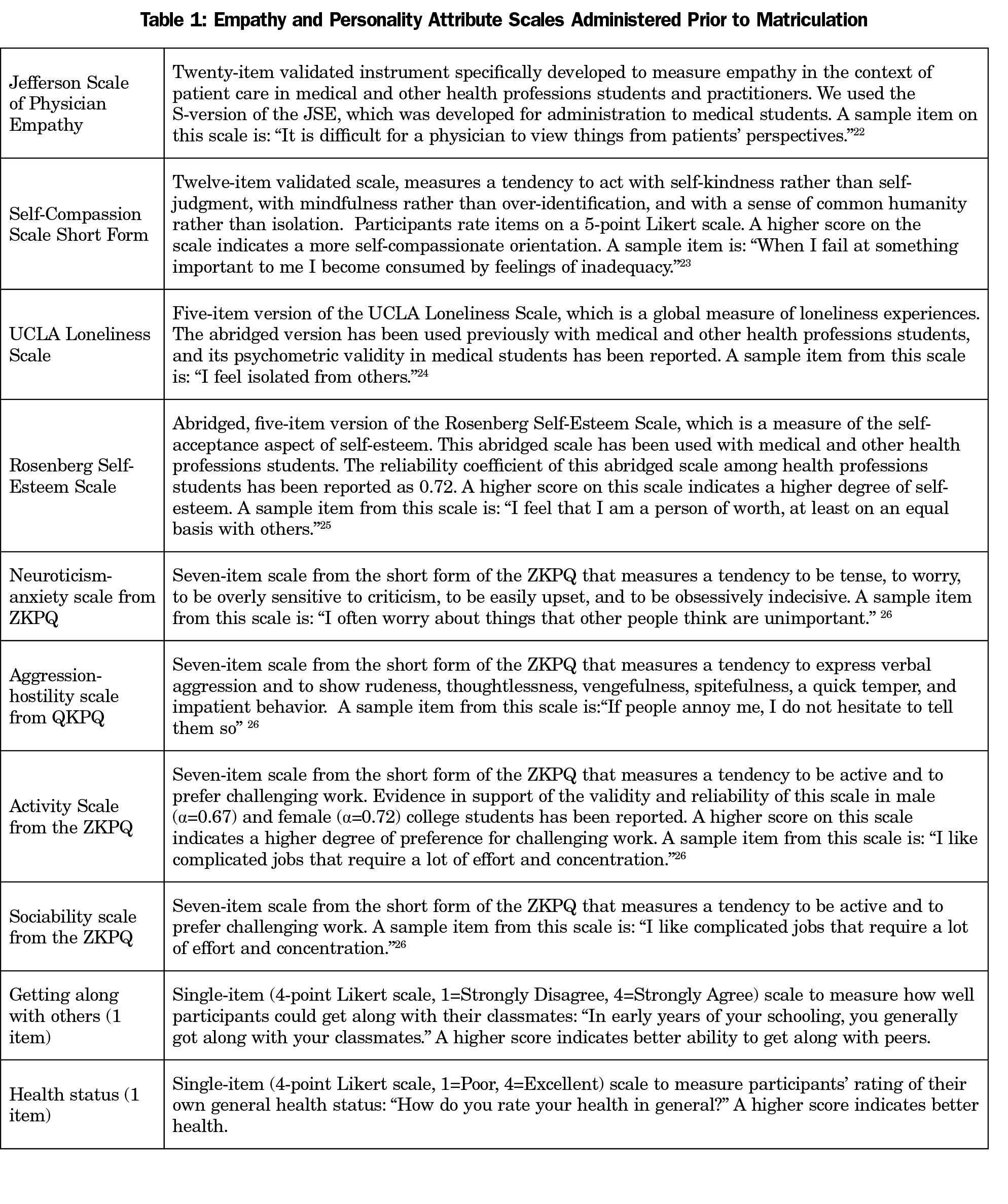

Additional instruments included the Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy,22 Self-Compassion Scale-Short Form,23 5-item UCLA Loneliness Scale,24 Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale,25 and the Zuckerman-Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire26 (Table 1).

Statistical Analyses

We transformed scores on all measures to a standard distribution to assess the magnitudes of group differences for all measures of personality attributes. We transformed scores in order to allow comparisons by gender, across times of administration, and to ensure reproducibility. We classified students into three categories of the IP scale: low (n=33, 13%); moderate (n=142, 55%); or high (n=82, 32%), based on cutoffs recommended by Clance,9 with adjustments made by combining the two highest-score categories into one group. The highest score categories represented frequent and intense levels of IP.

We contrasted groups to compare whether low, moderate, and high scorers on the IP scale were associated with measures of personality attributes and well-being. We used univariate and multivariate analysis of variance, and Duncan’s post-hoc multiple range tests to examine the main effects of IP, gender, and their interactions on measures of personality and well-being. We used the categorical form of the IP scale as predictors of psychological scale outcome scores.

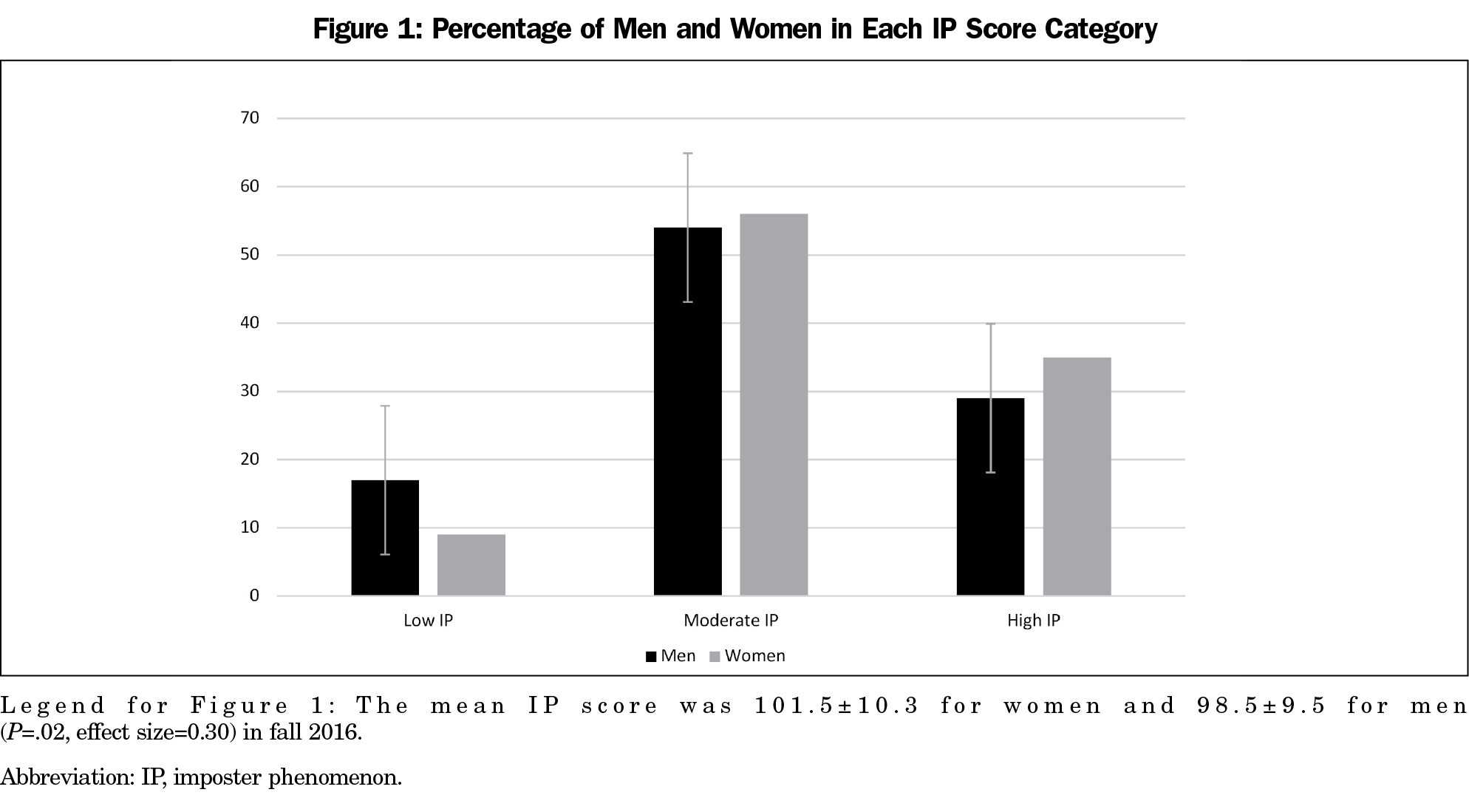

Complete data on the IP, self-compassion, and measures of personality were available for 257 students (128 men, 129 women; 97% of the first-year class). Thirty-two percent reported high degrees of IP, while 55% reported moderate or low IP (13%). A slightly higher proportion of women (35%, 45) than men (29%, 37), experienced high IP (Figure 1). Additionally, we found statistically significant differences between those with low, moderate, and high IP scores (P<.0001), and by gender on certain personality measures (P<.05) (Figure 2). Higher IP scores were associated with significantly lower scores on self-compassion (F (2, 251) =65.9); sociability (F (2, 251) =12.3); self-esteem (F (2, 251) =20.5; getting along with others (F (2, 251) =3.6; and health status (F (2, 251) =6.6) all P<.001. Conversely, students with lower IP scores obtained lower scores on neuroticism/anxiety (F (2, 251) =37.4) and loneliness (F (2, 251) =33.4) both P<.001; Figure 2). Furthermore, women scored significantly higher than men on the neuroticism/anxiety scale (Figure 2).

Prospectively, the percent of students with high IP scores (61 to >80) was greater at the end of the first year (spring 2017=49%) than at matriculation (fall 2016=29%; χ2=20.73; P<.001), suggesting that IP persisted and intensified over the first year (Figure 3). Conversely, the percentage of students with imposter scores from the moderate IP category measured in the fall (59%) significantly decreased, to 43%.

Our findings support the hypothesis that high degrees of IP are present in our students before matriculation, that they increase in incidence and degree over the first year, and are related to personality traits associated with emotional distress. Students with feelings of alienation from their peers and lower self-esteem and self-compassion were more likely to report IP. The degree of imposterism in students prior to matriculation was unexpectedly high. We believe this may be due in part to intense pressure and competition for admission experienced by medical school applicants, and should be explored further. Since IP is a malleable personality construct, and therefore responsive to intervention, supportive feedback and collaborative learning, mentoring by faculty, academic support, individual counseling and group discussions with peers are all helpful.5 We currently begin to address IP at first-year orientation, continuing in our counseling center through workshops, individual therapy, and group therapy. In our experience, for many students, the most powerful first step in addressing and ameliorating IP is normalizing this distorted and maladaptive self-perception through individual sessions with faculty and mentored small group discussions with peers.

We recognize that this study had several limitations. The population studied represents a sample of only first-year students measured at two points in time at a single medical college. Since IP was associated with personality traits linked to depression, anxiety, and burnout, early identification of IP in our learners may lead to more timely intervention to prevent distress and burnout in future physicians. Additional research is needed to determine how best to support students in overcoming IP during undergraduate medical education and future training.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: A version of these findings was presented at the 2019 Association of American Medical Colleges Group on Student Affairs Conference.

References

- Rotenstein LS, Ramos MA, Torre M, et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316(21):2214-2236. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.17324

- Rosenthal JM, Okie S. White coat, mood indigo—depression in medical school. N Engl J Med. 2005;353(11):1085-1088. doi:10.1056/NEJMp058183

- Dyrbye LN, Thomas MR, Shanafelt TD. Systematic review of depression, anxiety, and other indicators of psychological distress among U.S. and Canadian medical students. Acad Med. 2006;81(4):354-373. doi:10.1097/00001888-200604000-00009

- Dyrbye LN, Wittlin NM, Hardeman RR, et al. A prognostic index to identify the risk of developing depression symptoms among U.S. medical students derived from a national, four-year longitudinal study. Acad Med. 2019;94(2):217-226. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002437

- Seritan AL, Mehta MM. Thorny laurels: the impostor phenomenon in academic psychiatry. Acad Psychiatry. 2016;40(3):418-421. doi:10.1007/s40596-015-0392-z

- Vergauwe J, Wille B, Feys M, De Fruyt F, Anseel F. Fear of being exposed: the trait-relatedness of the impostor phenomenon and its relevance in the work context. J Bus Psychol. 2015;30(3):565-581. doi:10.1007/s10869-014-9382-5

- Leary MR, Patton KM, Orlando AE, Funk WW. The impostor phenomenon: self-perceptions, reflected appraisals, and interpersonal strategies. J Pers. 2000;68(4):725-756. doi:10.1111/1467-6494.00114

- Sandberg S. Lean in: Women, work and the will to lead. Knopf; 2013.

- TED. Fighting impostor syndrome [Video pressentation]. https://www.ted.com/playlists/503/fighting_impostor_syndrome. Published May 2015. Accessed July 16, 2019.

- Ahuna E. How did I get in here? The Chronicle. Published September 4, 2018. https://www.dukechronicle.com/article/2018/09/180904-ahuna. Accessed July 16, 2019

- Clance PR, Imes SA. The imposter phenomenon in high achieving women: dynamics and therapeutic intervention. Psychother Theory Res Prac. 1978;15(3):241-247. doi:10.1037/h0086006

- Chrisman SM, Pieper WA, Clance PR, Holland CL, Glickauf-Hughes C. Validation of the Clance imposter phenomenon scale. J Pers Assess. 1995;65(3):456-467. doi:10.1207/s15327752jpa6503_6

- Henning K, Ey S, Shaw D. Perfectionism, the imposter phenomenon and psychological adjustment in medical, dental, nursing and pharmacy students. Med Educ. 1998;32(5):456-464. doi:10.1046/j.1365-2923.1998.00234.x

- Hu KS, Chibnall JT, Slavin SJ. Maladaptive perfectionism, impostorism, and cognitive distortions: threats to the mental health of pre-clinical medical students. Acad Psychiatry. 2019; published online ahead of print. doi:10.1007/s40596-019-01031-z

- Villwock JA, Sobin LB, Koester LA, Harris TM. Impostor syndrome and burnout among American medical students: a pilot study. Int J Med Educ. 2016;7:364-369. doi:10.5116/ijme.5801.eac4

- Houseknecht VE, Roman B, Stolfi A, Borges NJ. A longitudinal assessment of professional identity, wellness, imposter phenomenon, and calling to medicine among medical students. Med Sci Educ. 2019;29(2):493-497. doi:10.1007/s40670-019-00718-0

- Oriel K, Plane MB, Mundt M. Family medicine residents and the impostor phenomenon. Fam Med. 2004;36(4):248-252.

- Legassie J, Zibrowski EM, Goldszmidt MA. Measuring resident well-being: impostorism and burnout syndrome in residency. J Gen Intern Med. 2008;23(7):1090-1094. doi:10.1007/s11606-008-0536-x

- Leach PK, Nygaard RM, Chipman JG, Brunsvold ME, Marek AP. Impostor phenomenon and burnout in general surgeons and general surgery residents. J Surg Educ. 2019;76(1):99-106. doi:10.1016/j.jsurg.2018.06.025

- LaDonna KA, Ginsburg S, Watling C. “Rising to the level of your incompetence”: what physicians’ self-assessment of their performance reveals about the imposter syndrome in medicine. Acad Med. 2018;93(5):763-768. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002046

- Gonnella JS, Hojat M, Veloski J. AM last page. The Jefferson Longitudinal Study of medical education. Acad Med. 2011;86(3):404. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31820bb3e7

- Hojat M, Mangione S, Nasca TJ, et al. The Jefferson Scale of Physician Empathy: development and preliminary psychometric data. Educ Psychol Meas. 2001;61(2):349-365. doi:10.1177/00131640121971158

- Raes F, Pommier E, Neff KD, Van Gucht D. Construction and factorial validation of a short form of the Self-Compassion Scale. Clin Psychol Psychother. 2011;18(3):250-255. doi:10.1002/cpp.702

- Russell D, Peplau LA, Cutrona CE. The revised UCLA Loneliness Scale: concurrent and discriminant validity evidence. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1980;39(3):472-480. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.39.3.472

- Crandall R. The measurement of self-esteem and related constructs. In: Robinson JP, Shaver PR, eds. Measures of Social Psychological Attitudes. Rev ed. Ann Arbor, MI: Survey Research Center, Institute for Social Research; 1973:45-168.

- Zuckerman M. Zuckerman-Kuhlman Personality Questionnaire (ZKPQ): an alternative five-factorial model. In: de Raad B, Perugini M, eds. Big Five Assessment. Seattle, WA: Hogrefe & Huber Publishers; 2002:377-396.

There are no comments for this article.