abstract: The COVID-19 pandemic, together with its resultant economic downturn, has unmasked serious problems of access, costs, quality of care, inequities, and disparities of US health care. It has exposed a serious primary care shortage, the unreliability of employer-sponsored health insurance, systemic racism, and other dysfunctions of a system turned on its head without a primary care base.

Fundamental reform is urgently needed to bring affordable health care that is accessible to all Americans. Over the last 40-plus years, our supposed system has been taken over by corporate stakeholders with the presumption that a competitive unfettered marketplace will achieve the needed goal of affordable, accessible care. That theory has been thoroughly disproven by experience as the ranks of more than 30 million uninsured and 87 million underinsured demonstrates.

Three main reform alternatives before us are: (1) to build on the Affordable Care Act; (2) to implement some kind of a public option; and (3) to enact single-payer Medicare for All. It is only the third option that can make affordable, comprehensive health care accessible for our entire population. As the debate goes forward over these alternatives during this election season, the likelihood of major change through a new system of national health insurance is becoming increasingly realistic. Rebuilding primary care and public health is a high priority as we face a new normal in US health care that places the public interest above that of corporate stakeholders and Wall Street investors. Primary care, and especially family medicine, should become the foundation of a reformed health care system.

For many years we have assumed that primary care should provide the foundation of a strong health care system, as it does in advanced countries around the world with systems of universal coverage. But we have fallen way short of that goal in the United States for a number of reasons, and our experience with the COVID-19 pandemic has made that goal even more important.

This article has four goals: (1) to describe how the COVID-19 pandemic, together with its accompanying economic downturn, has adversely impacted our system and primary care; (2) to bring historical perspective to transformational system changes over the last 50-plus years that have run counter to the growth of primary care; (3) to show why primary care and family medicine are essential to system reform; and (4) to consider how financing reform can bring universal coverage to all Americans and expand the essential role of primary care.

Impact of the COVID-19 Pandemic on Our System and Primary Care

The COVID-19 pandemic has stressed America’s health care system beyond its capacity on many fronts. The lack of preparedness has been exposed for all to see, together with the primary care shortage, the wide gulf between politics and the science of public health, the lack of leadership at the national level, and any kind of an effective national plan for bringing the pandemic under control.

These markers indicate the severity of stress on our system and primary care:

- Primary care physicians in smaller independent group practices, already in short supply, faced such a large drop in patient visits that they thought they may be forced to close their practices.1

- Almost all in-person outpatient visits were cancelled in many parts of the country between February and May 2020, with more than $15 billion in revenue losses even if reimbursement for telemedicine visits occurred.2

- Almost 2,000 low-cost and free health clinics closed temporarily and others worried about their financial futures as racial disparities widened.3

- Almost 27 million Americans lost their employer-sponsored health insurance due to the pandemic.4

- Continuing inequities by race are widespread, such as African Americans dying from COVID-19 at about twice the rate of White Americans.5

Although employer-sponsored health insurance has been the base of health insurance in the United States, with some 160 million Americans so covered before the pandemic, its frailty and unreliability became obvious during the pandemic. Wendell Potter, formerly an insider executive at Cigna and author of the book, Deadly Spin: An Insurance Company Insider Speaks Out on How Corporate PR Is Killing Health Care and Deceiving Americans, has this to say:

America needs to get out of the business linking health coverage to job status. Even in better times, this arrangement was a bad idea from a health perspective. Most Americans whose families depend on their employers for coverage are just a layoff away from being uninsured. And now, when many businesses are shutting down and considering layoffs, it’s a public health disaster.6

We are now just over 50 years beyond when family practice was recognized in 1969 as the 20th specialty in American medicine with the formation of the American Board of Family Practice. From the beginning it was a different kind of specialty—not one pursuing depth in a narrow area, but one that cut horizontally across the majority of health care conditions so as to serve as the foundation of the system. It was the hope of many in those early years that this would happen. But today we still have a health care system with no real foundation. Patients are on their own dealing with a confusing array of “providers”—the new name for physicians—with the challenge of finding a source of readily accessible comprehensive care with continuity.

Medical care in the United States has undergone a remarkable transformation over the last 50-plus years that has worked against the goal of placing primary care at the base of our system. Following are some of the major trends that have stood in the way.

Growth of Employer-Sponsored Health Insurance Into a Burgeoning Private Health Insurance Industry

Long past their early history with a mission of service, Blue Cross Blue Shield abandoned that goal for the business ethic of maximizing profits for themselves and their shareholders on Wall Street. After the 1970s and 1980s, Blue Cross and Blue Shield were forced to go for-profit in 1994 in order to better compete with many large private insurers entering a lucrative market.7 Twenty-six years later, the Blue Cross Blue Shield Association, which has 36 member companies including Anthem, has just agreed to a tentative antitrust settlement for $2.7 billion.8

Today, private insurers have many ways to profiteer on the backs of their enrollees, including imposing higher copays and deductibles, restricting choice through narrowed and ever-changing networks, exiting from unprofitable markets, and denial of claims, which have averaged 18% under the Affordable Care Act (ACA).9 They also impact the practices of physicians, especially those in primary care, as shown by these examples:

- Intrusion of increasing electronic health record/desk work into every physician-patient encounter, taking twice as much time as with patients.10

- Physicians and their staffs spend on average 14.6 hours, or about 2 work days, to obtain preauthorizations for tests or treatments.11

- Marked decline in independent practice, with more than 60% of physicians now employed by others, especially by hospital systems. 12

Increased Corporatization

Before the 1960s, most health care facilities were small, individually owned and operated companies. Ironically, the passage of Medicare and Medicaid in 1965 launched the entry of larger, investor-owned corporations into the delivery of health care. By 1984, the largest eight corporations together owned and operated 426 acute care hospitals, 102 psychiatric hospitals, 272 long-term care facilities, and 89 ambulatory care centers.13

Paul Starr, professor of sociology at Princeton University, called attention to this development in his 1982 book, The Social Transformation of American Medicine: The Rise of a Sovereign Profession and the Making of a Vast Industry:

The rise of the corporate ethos in medical care is already one of the most significant consequences of the changing structure of medical care. It permeates voluntary hospitals, government agencies, and academic thought, as well as profit-making medical care organizations. Those who talked about “health care planning” in the 1970s now talk about “health care marketing.” Everywhere one sees the growth of marketing mentality in health care. 14

Rise of the Medical-Industrial Complex

This term, patterned after President Eisenhower’s use in the 1950s of the term “military-industrial complex,” was coined in 1970 by John and Barbara Ehrenreich, together with the staff of the Health Policy Center in New York, as described in their 1970 book, The American Health Empire: Power, Profits and Politics.15 Increasingly, this complex has turned our system upside down by raising prices to what the traffic will bear, restricting access and choice of care, profiteering, and leading the way on the S&P 500.16

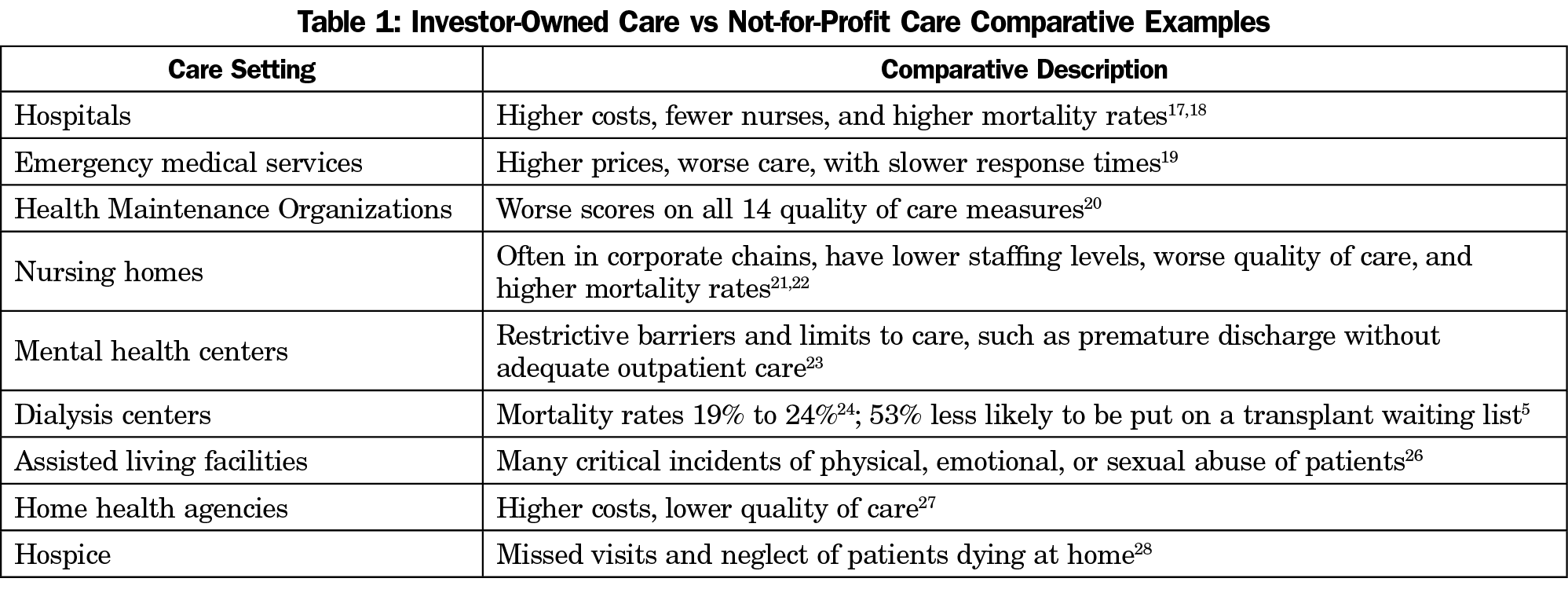

Today, we have a large medical industrial complex of investor-owned corporate stakeholders bent on maximizing revenue, charging what the traffic will bear, and cutting corners that adversely impact quality of care. Table 1 documents the extent to which investor-owned facilities and services have higher costs and lower quality of care compared to their not-for-profit counterparts.17-28

The logic of a generalist specialty that is trained and committed to the comprehensive and continuing care of patients anywhere in the country was apparent to health policy experts many years ago. Family medicine is the classic specialty for this role, as are general internists and general pediatricians for adults and children, respectively.

Primary care is essential at the base of our system for the care of patients with unselected and common health care conditions. As one of our specialty’s founders, Dr Gayle Stephens stated this in his classic paper, The Intellectual Basis of Family Practice:

The sine qua non is the knowledge and skill that allows a physician to confront relatively large numbers of unselected patients with unselected conditions and to carry on therapeutic relationships with patients.29

We are indebted to Dr Barbara Starfield for her pioneering work in defining the four essential elements of primary care: first-contact care; longitudinal continuity over time; comprehensiveness, with capacity to manage majority of health problems; and coordination of care with other parts of the health care system.30 A 2008 report from the World Health Organization, Primary Health Care: Now More Than Ever, called attention to the documented effectiveness, efficiency, and equity of primary care over the preceding 30 years, with this additional statement:

Essential features of a strong health system led by primary care are: accessibility (with no out-of-pocket payments), a person (not disease) focus over time, universality, a broad range of services in primary care, and coordination when people do not have care elsewhere .... Evidence at the macro level (eg, policy, payment, regulations) is now overwhelming: countries with a strong service for primary care have better outcomes at low cost. Systems that explicitly distribute resources according to population health needs (rather than demands), that eliminate co-payments, that assume responsibility for the financing of services within the primary care sector are more cost-effective.31

Since we have not developed a national plan for physician workforce planning that would build up primary care, we have let markets and technology drive the practice of medicine in this country. Organized medicine and the medical education establishment remain silent on what goal should be set for the generalist-specialist mix. Other countries with strong primary care set that ratio above 40%, or even 50% generalists.

Despite the ongoing primary care shortage in the United States, we have compelling evidence of how effective primary care is compared to a nonprimary care approach to care. Here are some specific examples:

- Greater primary care physician supply is associated with lower mortality.32

- Areas of the country with more primary care physicians have less use of intensive services, lower costs, and higher quality of care.33

- Polypharmacy is widespread among older adults who see multiple physicians, who don’t talk to one another, for common problems.34

- The Joint Commission on Accreditation of Healthcare Organizations has found that 80% of serious medical errors are associated with lack of communication or teamwork among specialists in hospitals.35

Today, no more than 10% of US medical graduates opt for family practice, and the majority of internists and pediatricians enter subspecialties. The United States is facing a shortage of 52,000 primary care physicians by 2025.36 Primary care physicians today are increasingly employed by large hospital systems, are pressed to provide more revenue to their employers, besieged with administrative work, have reduced clinical autonomy, and suffer increasing burnout.37

As a result of the shortage in primary care for first-contact and ongoing care of acute and chronic medical conditions, many patients seek care first at urgent care centers or emergency rooms, where they receive initial care without comprehensiveness, coordination or continuity of follow-up care. Then they are often ping-ponged around among specialists, in or out of the hospital, with higher expense and lower quality of care.

In this volatile time when the COVID-19 pandemic, together with its severe economic downturn, has revealed the reality of a failing health care system, we have three major alternatives before us to reform the system: (1) build on the Affordable Care Act (ACA) of 2010; (2) some kind of a public option; and (3) single-payer Medicare for All. Only the third option, however, can bring reliable universal coverage at affordable costs through a new program of national health insurance. It would provide comprehensive benefits based on medical need, not ability to pay, alleviate persistent disparities and inequities, and eliminate cost-sharing at the point of care.

Medicare for All would also bring:

- Full choice of hospitals and physicians anywhere in the country.

- Simplified administration with efficiencies through large scale cost controls.

- Negotiated fee schedules for physicians and other health professionals, who would remain in private practice and be protected from closing their doors during a pandemic.

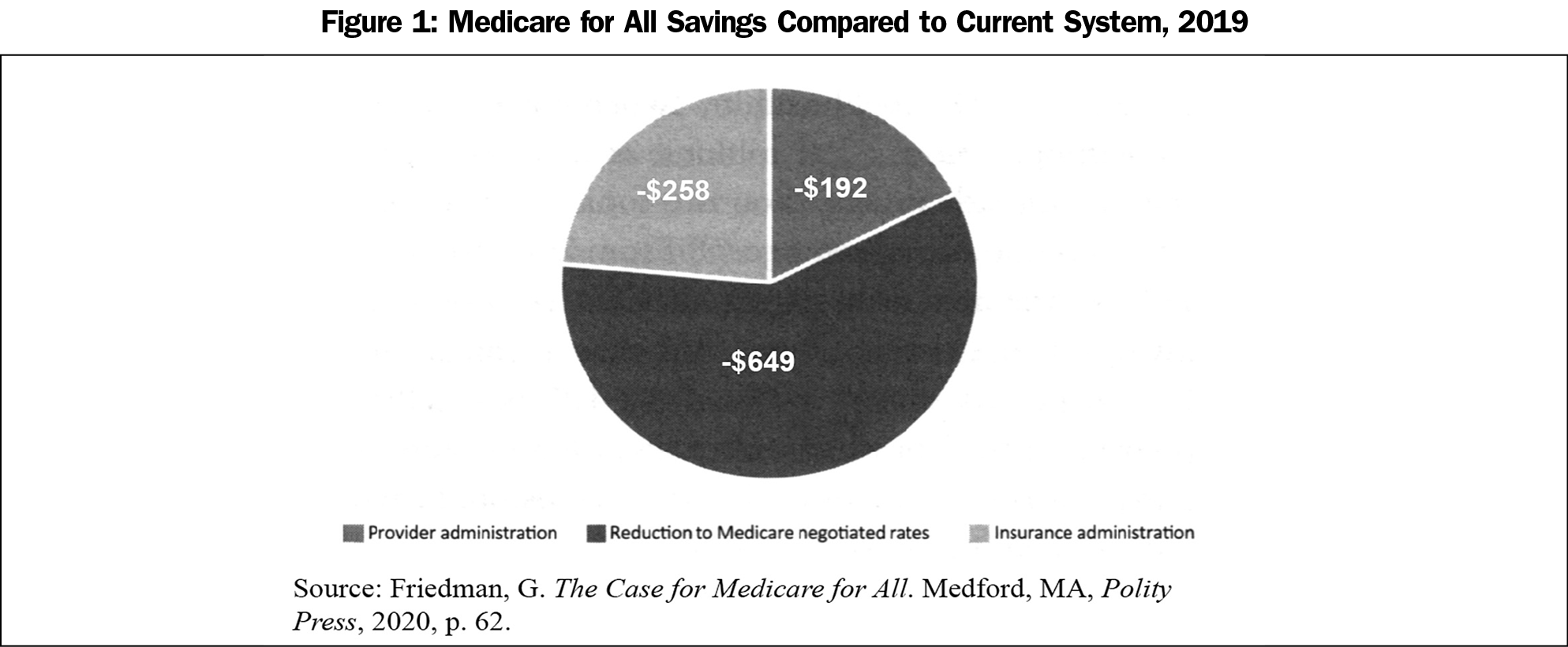

- Cost savings of more than $1 trillion a year that would enable universal coverage through a public, not-for-profit financing system (Figure 1).38

Had we had a single-payer system under Medicare for All at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic, we would could have controlled it much earlier with fewer lives lost and less disruption to our economy. The experience of Taiwan, where universal coverage was enacted with single-payer national health insurance in 1995, has shown just that. With evidence-based science and information technology, Taiwan has achieved better health outcomes at about one-third the cost of US health care. It started dealing with the pandemic early in January, with widespread testing, rapid results, effective contact tracing, and quarantine. Their economy has done well even without lockdown and with schools remaining open.39

Experience has told us that market-based strategies, despite the claims of their proponents, cannot contain prices and costs of health care. Markets in health care do not work as they do in other areas of our economy. In health care, there is asymmetry of information between providers and patients, urgency of time often restricts choice, prices are not transparent, and increasing consolidation among corporate giants gives them wide latitude to set prices as they grow market share. Jonathan Gruber, professor of economics at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and an architect of the Affordable Care Act 10 years ago, has recently acknowledged the predictable failure of market-based strategies to cost control in these words:

After decades of trying to figure out market-based solutions to cost control, I don’t think there are any. I think it’s time to regulate healthcare prices.40

These are other health care and financial advantages of enacting a program of national health insurance, as is being brought forward in the House of Representatives through HR 1384 (Expanded and Improved Medicare for All), which already has the support of 135 Representatives and 30 members of the Senate. Under this resolution:

- Primary care and public health would be better funded.

- A recent Yale study projects that 68,000 deaths a year would be prevented, together with savings of more than $450 billion a year.41

- Risk for the costs of illness and accidents would be shared across our entire population of 330 million Americans.

- The poverty level can be reduced by more than 20% by eliminating cost sharing, self-payments and other out-of-pocket costs at the point of care.42

- The labor market and economy can be helped by allowing employers to redirect money they have been spending on health care to their employees’ wages.43

- Primary care will be expanded with an emphasis on smaller, community-based independent primary care practices, not corporate Walmarts that are planning and hoping to fill the void of primary care.44

- Physician workforce planning by specialty will be established with the intent to reverse critical shortages, especially in primary care and psychiatry.

We are now at a critical juncture in US health care where fundamental reform is required. If we can seize this opportunity to reorganize health care financing around Medicare for All in transitioning toward a not-for-profit system, we can improve access, quality, and outcomes of care for all Americans through universal coverage. Primary care, and especially family medicine, should be an essential part of the new normal at the base of a new and improved system.

References

- Slavitt A, Mostashari F. COVID-19 is battering independent physician practices. Stat. 2020.

- Basu S, Phillips RS, Phillips R, Peterson LE, Landon BE. Primary care practice finances in the United States amid the COVID-19 pandemic. Health Affairs. 39(9). https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2020.00794. Published online June 25, 2020. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- Armour S. Health clinics shut in needy areas. The Wall Street Journal. July 13, 2020: A3.

- Ollove M. Medicaid rolls surge, adding to budget woes. Stateline. https://www.pewtrusts.org/en/research-and-analysis/blogs/stateline/2020/06/16/medicaid-rolls-surge-adding-to-budget-woes. Published June 16, 2020. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- Morath, E, Omeokwe, A. Virus obliterates black job market. The Wall Street Journal. June 10, 2020: A1.

- Potter W. Millions of Americans are about to lose their health insurance in a pandemic. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2020/mar/27/coronavirus-pandemic-americans-health-insurance. Published March 27, 2020. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- Reich RB. The Common Good. New York: Alfred A. Knopf; 2018:80.

- Mathews AW, Kendall B. Blue Cross Blue Shield strikes tentative antitrust settlement. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/blue-health-insurers-reach-tentative-antitrust-settlement-for-2-7-billion-11600967231. Published September 25, 2020. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- Silvers JB. This is the most realistic path to Medicare for All. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/10/15/opinion/medicare-for-all-insurance.html. Published October 16, 2019. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- Sinsky C, Tutty M, Colligan L. Allocation of physician time in ambulatory practice. Ann Intern Med. 2017;166(9):683-684. doi:10.7326/L17-0073

- American Medical Association. 2017 Prior Authorization Physician Survey. https://www.ama-assn.org/sites/ama-assn.org/files/corp/media-browser/public/arc/prior-auth-2017.pdf. Chicago: AMA; December 2017.

- Rosenthal E. Apprehensive, many doctors shift to jobs with salaries. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2014/02/14/us/salaried-doctors-may-not-lead-to-cheaper-health-care.html. Published February 13, 2014. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- Gray BH, ed. For-Profit Enterprise in Health Care. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 1986:40.

- Starr P. The Social Transformation of American Medicine. New York: Basic Books; 1982:448.

- Ehrenreich B, Ehrenreich J. The American Health Empire: Power, Profits and Politics. New York: Vantage Books; 1970:29-39.

- Fulton BD. Health and market competition trends in the United States: evidence and policy responses. Health Aff (Millwood). 2017;36(9):1530-1538. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0556

- Silverman EM, Skinner JS, Fisher ES. The association between for-profit hospital ownership and increased Medicare spending. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(6):420-426. doi:10.1056/NEJM199908053410606

- Yuan Z, Cooper GS, Einstadter D, Cebul RD, Rimm AA. The association between hospital type and mortality and length of stay: a study of 16.9 million hospitalized Medicare beneficiaries. Med Care. 2000;38(2):231-245. doi:10.1097/00005650-200002000-00012

- Ivory D, Protess B, Daniel J. When you dial 911 and Wall Street answers. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/06/26/business/dealbook/when-you-dial-911-and-wall-street-answers.html. Published June 25, 2016. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- Himmelstein DU, Woolhandler S, Hellander I, Wolfe SM. Quality of care in investor-owned vs not-for-profit HMOs. JAMA. 1999;282(2):159-163. doi:10.1001/jama.282.2.159

- Harrington C, Olney B, Carrillo H, Kang T. Nurse staffing and deficiencies in the largest for-profit nursing home chains and chains owned by private equity companies. Health Serv Res. 2012;47(1 Pt 1):106-128. doi:10.1111/j.1475-6773.2011.01311.x

- Whoriskey P. Keating D. Overdoses, bedsores, broken bones: What happened when a private-equity firm sought to care for society’s most vulnerable? https://www.washingtonpost.com/business/economy/opioid-overdoses-bedsores-and-broken-bones-what-happened-when-a-private-equity-firm-sought-profits-in-caring-for-societys-most-vulnerable/2018/11/25/09089a4a-ed14-11e8-baac-2a674e91502b_story.html. The Washington Post. Published November 25, 2018. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- Munoz, R. How health care insurers avoid treating mental illness. San Diego Union Tribune, May 22, 2002.

- Devereaux PJ, Schünemann HJ, Ravindran N, et al. Comparison of mortality between private for-profit and private not-for-profit hemodialysis centers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2002;288(19):2449-2457. doi:10.1001/jama.288.19.2449

- Garg PP, Frick KD, Diener-West M, Powe NR. Effect of the ownership of dialysis facilities on patients’ survival and referral for transplantation. N Engl J Med. 1999;341(22):1653-1660. doi:10.1056/NEJM199911253412205

- Pear R. US pays billions for ‘assisted living,’ but what does it get? New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2018/02/03/us/politics/assisted-living-gaps.html. Published February 13, 2018. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- Cabin W, Himmelstein DU, Siman ML, Woolhandler S. For-profit medicare home health agencies’ costs appear higher and quality appears lower compared to nonprofit agencies. Health Aff (Millwood). 2014;33(8):1460-1465. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2014.0307

- Waldman, P. Preparing Americans for death lets hospices neglect end of life. Bloomberg. https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2011-07-22/preparing-americans-for-death-lets-for-profit-hospices-neglect-end-of-life. Published July 22, 2011. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- Stephens GG. The intellectual basis of family practice. J Fam Pract. 1975;2(6):423-428.

- Starfield B. Is primary care essential? Lancet. 1994;344(8930):1129-1133. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(94)90634-3

- Rawaf S, De Maeseneer J, Starfield B. From Alma-Ata to Almaty: A new start for primary health care. Lancet. 2008. 372(9647)1265-1367. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)61524-X.

- Basu S, Berkowitz SA, Phillips RL, Bitton A, Landon BE, Phillips RS. Association of Primary Care Physician Supply With Population Mortality in the United States, 2005-2015. JAMA Intern Med. 2019 Apr 1;179(4):506-514. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7624.

- Parchman ML, Culler S. Primary care physicians and avoidable hospitalizations. J Fam Pract. 1994;39(2):123-128.

- Landro L. Medication overload. The Wall Street Journal. October 1, 2016: D1.

- Landro L. Joint Commission-Hospital Collaboration targets hand-offs. The Wall Street Journal. https://www.wsj.com/articles/BL-HEB-22418. Published October 21, 2010. Accessed Octover 19, 2020.

- Petterson SM, Liaw WR, Phillips RL Jr, Rabin DL, Meyers DS, Bazemore AW. Projecting US primary care physician workforce needs: 2010-2025. Ann Fam Med. 2012;10(6):503-509. doi:10.1370/afm.1431

- Kane L. Medscape National Physician Burnout, Depression and Suicide Report 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-lifestyle-burnout-depression-6011056. Published January 16, 2019. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- Friedman G. The Case for Medicare for All. Medford, MA: Polity Press; 2020:62.

- Cheng Tsung-Mei. When a Trump official praised single-payer health care. New York Daily News. https://www.nydailynews.com/opinion/ny-oped-when-a-republican-praised-single-payer-health-care-20200814-6fbbzyenn5f7nj6ruupth3wbgy-story.html. Published August 14, 2020. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- Miller C. Q & A. ACA architect predicts the future of healthcare. American Healthcare Journal. https://americanhealthcarejournal.com/2020/09/09/qa-aca-architect-predicts-the-future-of-healthcare/. Published September 9, 2020. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- Galvani AP, Parpia AS, Foster EM, Singer BH, Fitzpatrick MC. Improving the prognosis of health care in the USA. Lancet. 2020;395(10223):524-533. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(19)33019-3

- Bruenig M. Medicare for All would cut poverty by over 20 percent. People’s Policy Project. https://www.peoplespolicyproject.org/2019/09/12/medicare-for-all-would-cut-poverty-by-over-20-percent/. Published September 12, 2019. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- Bivens J. Fundamental reform like ‘Medicare for All’ would help the labor market. Economic Policy Institute. Published March 5, 2020. Accessed October 19, 2020.

- Kim A, Heiser S, McKinney L et al. The day after tomorrow must include independent primary care. Health Affairs Blog. https://ramaonhealthcare.com/the-day-after-tomorrow-must-include-independent-primary-care/. Published July 23, 2020. Accessed October 19, 2020.

There are no comments for this article.