Family medicine is rapidly transforming to meet the needs of patients and populations. New interprofessional collaborative practice models are incorporating critical building blocks such as team-based care, leadership at all levels, partnerships with patients, population management, and care coordination to achieve the goal of high-performing primary care.1,2 Preparing family medicine residents for patient-engaged, interprofessional practice to achieve health equity is critical for contemporary family medicine residency education. Family medicine as a discipline must agree on principles and strategies for creating clinical learning environments where residents can excel as effective members of collaborative interprofessional practice teams.

COMMENTARIES

The Importance of Interprofessional Practice in Family Medicine Residency Education

Christine Arenson, MD | Barbara Fifield Brandt, PhD

Fam Med. 2021;53(7):548-555.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2021.151177

The practice of family medicine is undergoing rapid transformation, with increasing recognition that family physicians can most effectively meet the needs of individual patients and populations within the context of highly effective interprofessional teams. A substantive evidence base exists to support effective workplace learning by practicing health care teams and learners, much of which has been developed in primary care teaching practices. A strong national consensus now emphasizes the importance of the interprofessional clinical learning environment, including in graduate medical education. Evidence for the impact of improved team function on quadruple aim outcomes is increasingly robust. The World Health Organization, Interprofessional Education Consortium, National Collaborative for Improving the Clinical Learning Environment, and National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education have developed evidence-based approaches and tools for improving interprofessional collaboration to improve important health outcomes in the clinical learning environment. Embracing the practice as the curriculum and preparing our residency graduates to work within high-functioning interprofessional collaborative practice teams, family medicine has the opportunity to lead the way in demonstrating the value of effective interprofessional practice across health care settings, including virtual teaming, to improve the health of the communities we serve, and across the nation.

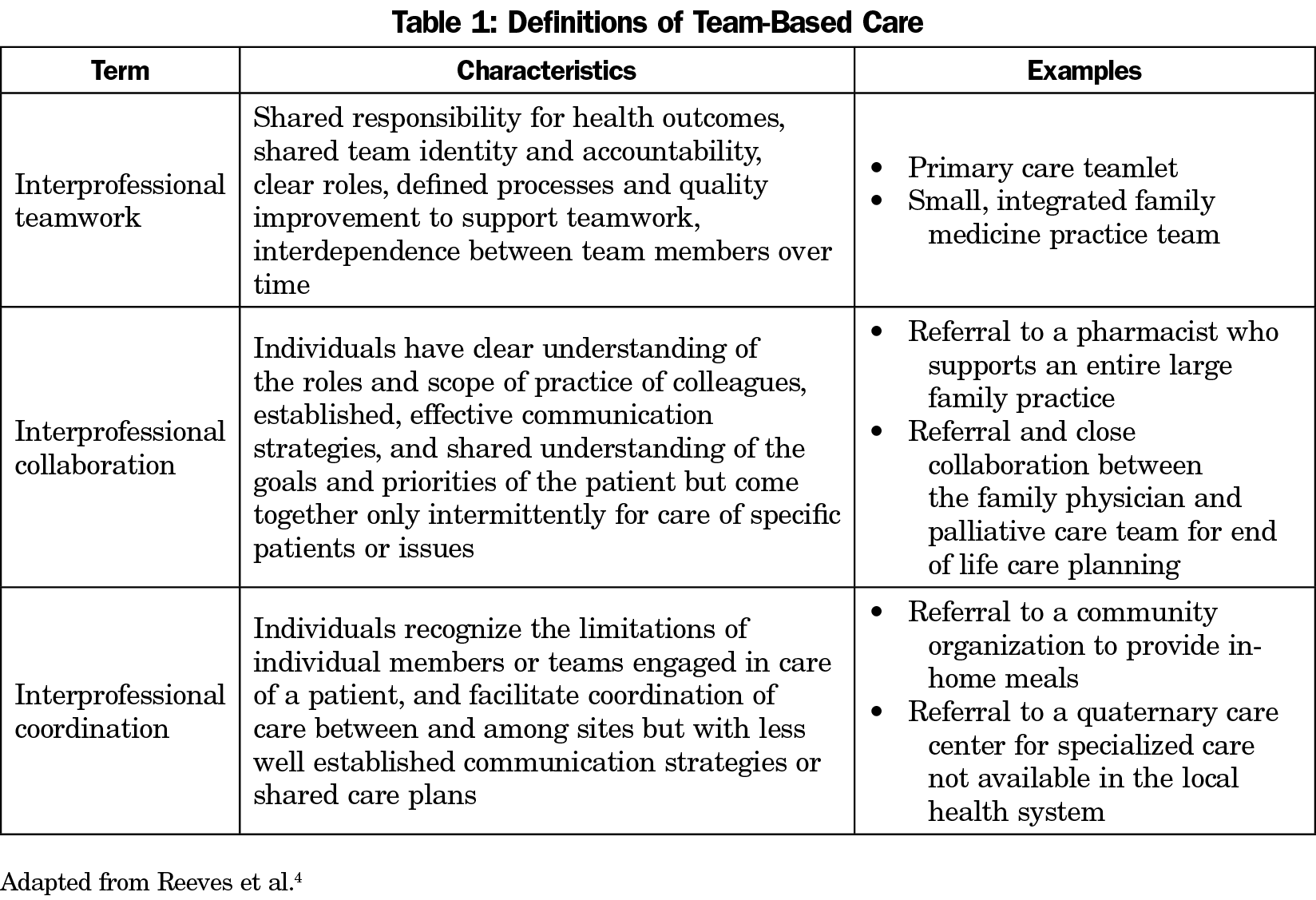

Primary care practice models are moving beyond traditional multidisciplinary practice with providers working side by side with little integration. In contrast, health care and family medicine are moving toward interprofessional practice models that incorporate different nonphysician health professionals3 and nonprofessionals such as medical assistants.1 However, terms such as “teams,” and “team-based care” are often used in the literature to describe very different types of interprofessional work.4 The differences matter to health outcomes, and family medicine residents have the opportunity to experience and learn in a wide variety of interprofessional clinical settings. These range from interprofessional teamwork to interprofessional collaboration and coordination, as described in Table 1.

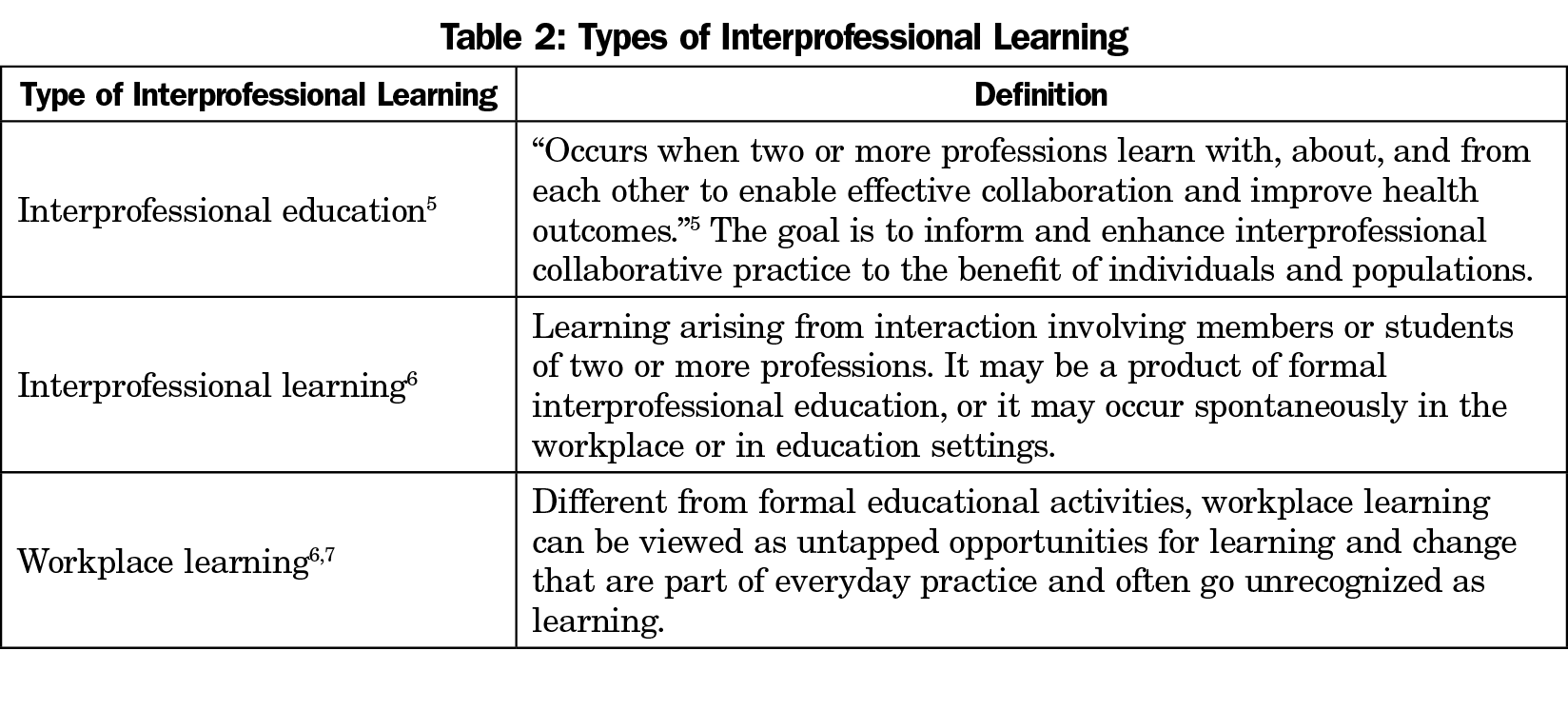

Family medicine educators are increasingly recognizing the concept of “practice as curriculum,” positioning family medicine residency education precisely in the nexus of learning and primary care practice transformation.5-7 Table 2 describes interprofessional education, interprofessional learning, and workplace learning, each of which support family medicine education and practice transformation.

The Interprofessional Education Collaborative (IPEC) has articulated four core competency domains for interprofessional collaborative practice: Interprofessional Teamwork and Team-Based Practice, Interprofessional Communication Practices, Roles and Responsibilities for Collaborative Practice, and Values and Ethics for Interprofessional Practice.8 These four domains are envisioned within the context of patient- and family-centered practice that is community- and population-oriented.

In addition, the National Collaborative for Improving the Clinical Learning Environment (NCICLE) is an interprofessional forum committed to improving the educational experience and patient care outcomes within clinical learning environments. Convened by the Association for Graduate Medical Education, NCICLE’s work is informed by clinical learning environment review (CLER) visits at graduate medical education programs across the nation. NCICLE has identified characteristics of high-functioning interprofessional clinical learning environments: patient-centeredness, a continuum of learning, reliable communications, team-based care, shared accountability, evidence-based practice centered on interprofessional care.9 These priorities reinforce the importance of “practice as curriculum” for family medicine education.

Important learning occurs at the nexus of education and practice, with residents and other team members sharing responsibility for learning and doing the work of patient-engaged interprofessional collaborative practice. IPEC and NCICLE frameworks inform didactic curriculum and simulation that prepare residents for authentic workplace learning that will improve quality, support practice transformation and drive health equity locally while preparing tomorrow’s family physician leaders.

Measuring Impact

The 2015 Institute of Medicine report6 on measuring the impact of interprofessional education advocates for the development of evidence for the virtuous cycle of learning and collaborative practice to improve patient outcomes. The National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education has led development and dissemination of knowledge regarding effective interprofessional practice and education (the new IPE) to improve health outcomes.10 Iterative developmental evaluation using a suite of validated tools to self-assess team functioning and patient and learning outcomes, allows real-time adjustments to support learning of individual team members, including residents, and ongoing interprofessional practice transformation.

Increasingly, family medicine teams include advanced practice providers, nurses, behavioral health providers, social workers, pharmacists, care coordinators, and community health workers. Family medicine residents must understand the roles of these professionals, as well as paraprofessional and nonprofessional team members such as medical assistants, peer educators, patient advisors, registrars, and others. Ambulatory care teams must address additional challenges as many family medicine practices are chronically underresourced, with key members of the team missing, or present only virtually as the primary care team partners with other specialties and community resources to meet the comprehensive needs of each patient.

Patient care extends beyond the walls of our practices, and family medicine residents must broaden their perspective with a deep understanding of multisector collaborations including home care providers, community-based agencies, schools, religious institutions, families, law enforcement, attorneys, and others who contribute to health and health equity for individuals and populations. This “community as curriculum” focus supports residents to learn, and practice to address, social determinants of health and health equity. Family medicine residents also experience working within teams in other settings including hospitals, delivery rooms, homes, and skilled nursing facilities. The critical common element of every care team must be the patient, including their family and community as appropriate, fully engaged in designing their health care. The family physician must be expert at helping each patient form the team they need, whether for wellness, acute care, or chronic disease management, across care settings and over the patient’s lifetime.

Physicians have historically been accultured to take total responsibility for the care of their patients as the team leader. Effective interprofessional collaborative practice requires deeper engagement of all team members, including patients and families, with shared understanding of mutual roles, shared values and shared responsibility.

Future family physicians should be educated for interprofessional practice within the context of the important, ongoing work of practice transformation to achieve the Quadruple Aim and achieve health equity. Fiscella et al have identified six elements from team science that are “particularly relevant to primary care practice” and thus to family medicine residency education in interprofessional team-based practice, including understanding practice conditions that support effective teamwork; team cognition; leadership and coaching; cooperation and team cohesion; coordination; and communication.11 Multiple regional and national learning collaboratives, including the Veterans Affairs Centers of Excellence in Primary Care Education12 and Improvement Cubed (I3) Collaborative13 have demonstrated significant impact on outcomes for patients and teams and learning outcomes for interprofessional practice.

The IPEC domains, informed by NCICLE’s insights around the interprofessional clinical learning environment, offer an opportunity to tailor family medicine residency curriculum that engages the entire practice team to develop the knowledge, skills, and attitudes critical to effective collaborative practice. Residents must then internalize these lessons through authentic practice-based learning, including working within interprofessional teams to design, implement, and assess quality improvement and practice transformation efforts with demonstrable impact on meaningful patient outcomes. Family medicine residents will benefit from opportunities to reflect on the wide variety of teams they encounter in training, including those that are high functioning and those with significant dysfunction, in order to recognize and adopt best practices for team performance in their future practice environments.

Many medical students are now exposed to these principles before residency. However, interprofessional education in undergraduate medical education remains uneven and largely classroom based. Family medicine residencies will need to assess core knowledge, skills, and attitudes for interprofessional practice at program entry and periodically throughout the curriculum. While most education for interprofessional practice should occur in the context of patient care, practice improvement and population health, core didactic content remains essential preparation.

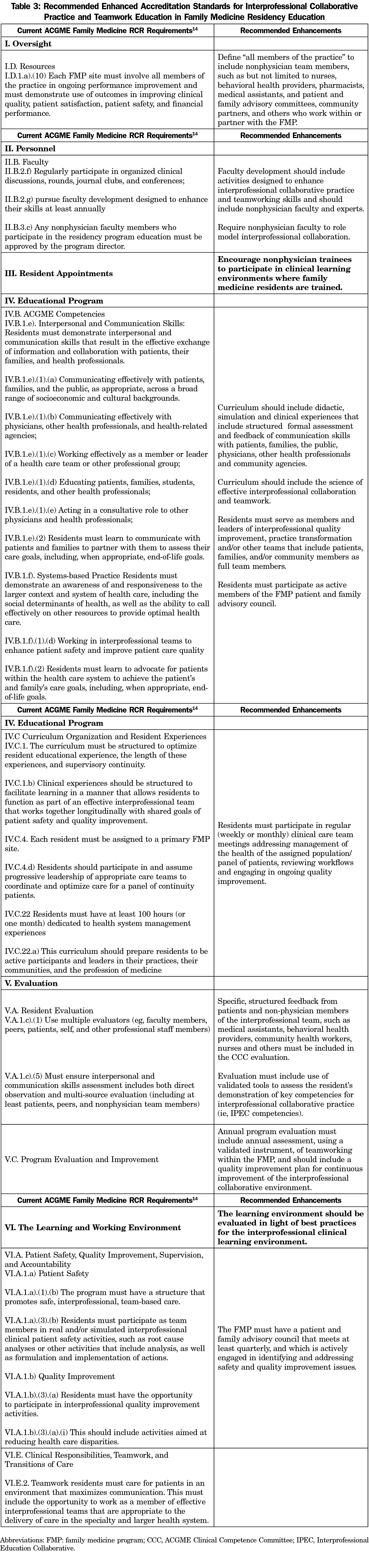

While the current Family Medicine Milestones reference “mobilizing” or “leading” multidisciplinary teams and engaging patients, families, and community resources,14 the language does not fully reflect contemporary understanding of patient-engaged interprofessional collaborative practice to achieve the Quadruple Aim.15 Table 3 provides specific recommendations to fully prepare family medicine residents for patient-engaged interprofessional practice that promotes health equity.

Family medicine has provided significant leadership in the national movement toward interprofessional education to inform collaborative practice. This energy and expertise should be harnessed to create innovative models to educate family medicine residents for interprofessional practice and team-based care across health care settings. We have a unique opportunity to build on this foundation to practice “interprofessional practice by the zip code” that improves health and health equity of our local communities while preparing our graduates to be the collaborative practice leaders of the future.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: A brief overview of an earlier version of this commentary was presented on December 6, 2020 as part of the Starfield Summit: “Re-Envisioning Family Medicine Residency Education.”

References

- Goldberg DG, Beeson T, Kuzel AJ, Love LE, Carver MC. Team-based care: a critical element of primary care practice transformation. Popul Health Manag. 2013;16(3):150-156. doi:10.1089/pop.2012.0059

- Bodenheimer T, Ghorob A, Willard-Grace R, Grumbach K. The 10 building blocks of high-performing primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(2):166-171. doi:10.1370/afm.1616

- Jabbarpour Y, Jetty A, Dai M, Magill M, Bazemore A. The evolving family medicine team. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33(4):499-501. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2020.04.190397

- Reeves S, Xyrichis A, Zwarenstein M. Teamwork, collaboration, coordination, and networking: why we need to distinguish between different types of interprofessional practice. J Interprof Care. 2018;32(1):1-3. doi:10.1080/13561820.2017.1400150

- World Health Organization. Framework for Action on Interprofessional Education and Collaborative Practice. Geneva, Switzerland:WHO; 2010.

- Institute of Medicine. Measuring the Impact of Interprofessional Education on Collaborative Practice and Patient Outcomes. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2015.

- Nisbet G, Lincoln M, Dunn S. Informal interprofessional learning: an untapped opportunity for learning and change within the workplace. J Interprof Care. 2013;27(6):469-475. doi:10.3109/13561820.2013.805735

- Interprofessional Education Collaborative. Core Competencies for Interprofessional Collaborative Practice: 2016 Washington, DC: Interprofessional Education Collaborative. https://nebula.wsimg.com/2f68a39520b03336b41038c370497473?AccessKeyId=DC06780E69ED19E2B3A5&disposition=0&alloworigin=1. Accessed 11/15/2020.

- Weiss KB, Passiment M, Riordan L, Wagner R; National Collaborative for Improving the Clinical Learning Environment IP-CLE Report Work Group. Achieving the Optimal Interprofessional Clinical Learning Environment: Proceedings From an NCICLE Symposium. Published January 18, 2019. doi:10.33385/NCICLE.0002

- Delaney CW, AbuSalah A, Yeazel M, Stumpf Kertz J, Pejsa L, Brandt BF. National center for interprofessional practice and education IPE core data set and information exchange for knowledge generation. J Interprof Care. August 18, 2020: doi:10.1080/13561820.2020.1798897

- Fiscella K, Mauksch L, Bodenheimer T, Salas E. Improving care teams’ functioning: recommendations from team science. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf. 2017;43(7):361-368. doi:10.1016/j.jcjq.2017.03.009

- Gilman SC, Chokshi DA, Bowen JL, Wirtz K and Cox M. Connecting the dots: interprofessional health education and delivery system redesign at the Veterans Health Administration. Academic Medicine 2014; 89(8):1113-1116. doi:1097/ACM.0000000000000312

- Newton W, Baxley E, Reid A, Stanek M, Robinson M, Weir S. Improving chronic illness care in teaching practices: learnings from the I³ collaborative. Fam Med. 2011;43(7):495-502.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical education in Family Medicine. Editorial revision: effective July 1, 2020. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/120_FamilyMedicine_2020.pdf?ver=2020-06-29-161615-367. Accessed 3/14/2021.

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-576. doi:10.1370/afm.1713

Lead Author

Christine Arenson, MD

Affiliations: National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN

Co-Authors

Barbara Fifield Brandt, PhD - National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education, University of Minnesota, Minneapolis, MN

Corresponding Author

Christine Arenson, MD

Correspondence: National Center for Interprofessional Practice and Education and Professor, Department of Family Medicine and Community, University of Minnesota, 1499 Blake St, Apt 7M, Denver, CO 80202. 267-974-7986.

Email: carenson@umn.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.