Hospital care costs represents the lion’s share of health care spending in the United States. Since 1970, the annual cost of hospital care has increased from $9 billion to current spending of over $1.1 trillion.1 The advent of hospital medicine, the discipline dedicated to caring for adults hospitalized for nonobstetric medical conditions, largely arose from the desire to control the cost of inpatient care, reduce patients’ length of stay, and promote patient safety.

Family physicians are a growing part of the hospital medicine workforce,2 and while we remain the minority relative to internal medicine, we bring a valuable and distinct perspective. Our training in the biopsychosocial model contextualizes patients and their illness, which promotes inquiry into the drivers of hospitalization. Further, family medicine’s strong emphasis on outpatient medicine makes the pitfalls of transitions of care more visible. Finally, family physicians are responsible stewards of resources. In providing high-value care for less cost and in practicing judicious restraint in ordering diagnostic testing, family physicians are a key partner in addressing rising costs and preventing iatrogenic harm.3

In turn, our specialty must work to retain our position in hospital medicine. The wards offer unparalleled training ground for family medicine (FM) residents to gain comfort in managing medically complex patients, a key skill for primary care. Furthermore, the inclusion of inpatient medicine in FM’s scope of practice provides unique insights that are vital to our role in shaping the future of the profession through participation in research, hospital administration, and health policy.

However, sustaining family physicians in hospital medicine roles requires a specialty-wide alignment and revised approach. In this commentary, we present a vision for the future of family medicine’s role in hospital medicine and its implications for residency training. Inclusive in our discussion are the various roles family physicians take in caring for admitted adult patients (apart from rounding solely on one’s own primary care patients), ranging from full-time hospitalists to those who incorporate it as part of full-spectrum FM. We draw upon lessons learned from our work at Boston Medical Center (BMC) to illustrate key facets of the practice of hospital medicine. BMC is New England’s largest safety-net hospital and the training site for the Boston University FM residency.

Our hospitalist model at BMC is built upon the three pillars of our specialty: continuity, patient-centeredness, and clinical excellence. Established in 2007 as a regionalized 26-bed unit, our attendings are fully dedicated to patient care and resident teaching while on service for 7-day stretches. The inclusion of hospitalists in our model is intentional given their benefits to resident education and in modeling this potential career path.4 While our service is separate from internal medicine teams, we strive to maintain a strong alliance to the mutual benefit of both services and hospital efficiency. For example, as COVID-19 cases rose in Boston in spring 2020, we worked alongside internal medicine to create 14 COVID-19 care teams, one-third of which were run by our service.

FM-led hospital medicine services should retain the principle of continuity and caring for a defined population. Our model focuses on providing inpatient care for patients of the Boston HealthNet, an alliance between BMC and 14 local community health centers (CHCs). Defining this smaller population relative to the overall inpatient census creates more opportunity to care for patients across multiple hospitalizations and incentivizes efforts to prevent readmissions. Further, most of our attendings and residents provide outpatient care at these same CHCs, which improves understanding of the resources each offers. We have developed systems to streamline scheduling posthospital follow-up appointments and facilitate communication between primary care providers and inpatient teams. To reduce patient handoffs we also care for our patients who require step-down level of care.

Patient-centered inpatient care requires effective communication with patients, caregivers, and other loved ones (with consent). Hospital medicine teams should be trained in counseling techniques that incorporate patient preferences, such as shared decision-making, implement strategies to combat disparities from provider bias, such as antibias training, and ensure use of interpreters for patients with limited English proficiency. On our service at BMC, we include documentation of health care proxy in admission workflows and include in progress notes when loved ones were last updated.

In line with the biopsychosocial model, FM should continue to create multidisciplinary inpatient care environments to address patients’ holistic needs. Involvement of nurses, pharmacists, social workers, and consult services that cater to specific needs, such as addiction medicine, is essential. Both regionalization—localizing each team’s patients one geographic unit—and daily interdisciplinary huddles to review the plan for each patient can facilitate teamwork. Such supports are especially essential at discharge when patients and caregivers may feel overwhelmed. The BMC FM inpatient unit designed Project RED to improve the discharge process through involvement of nurse educators and pharmacists, which improved patient satisfaction and reduced re-admission rates by approximately 30%.5

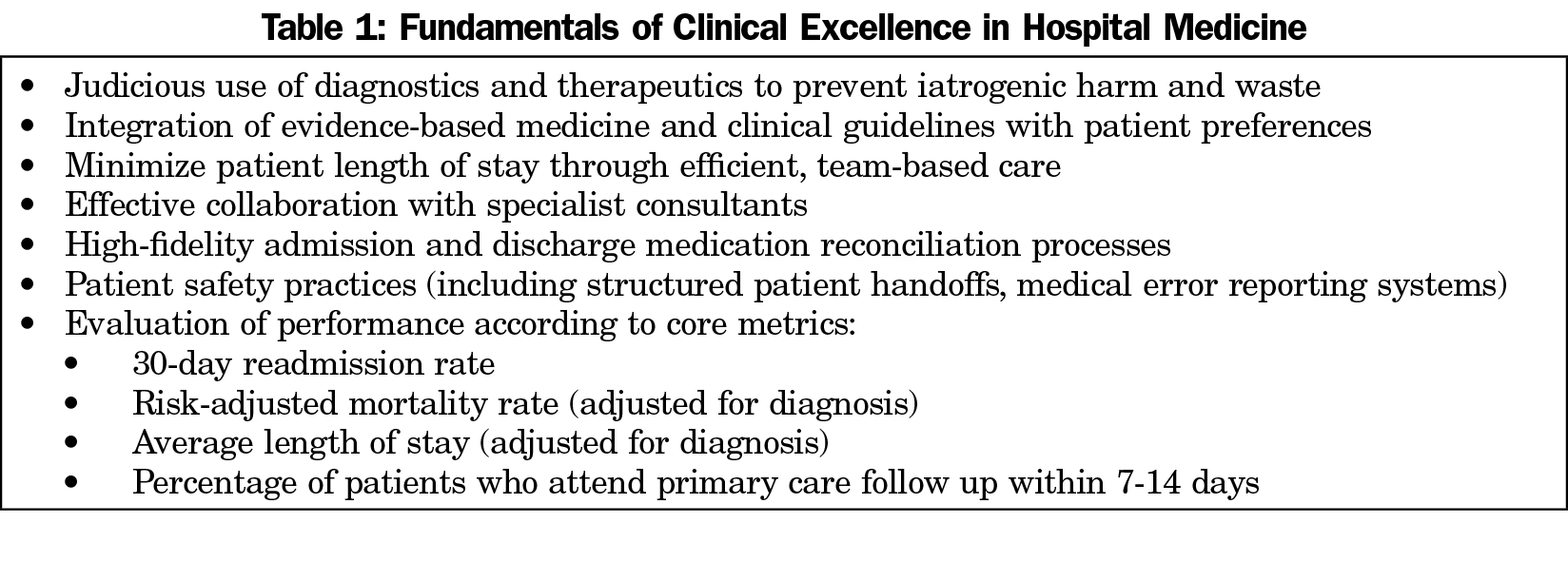

While it is beyond the scope of this article to provide an exhaustive review of criteria for clinical excellence in hospital medicine, we summarize systems resources and care principles that guide our inpatient unit and BMC in Table 1. While there is a lack of evidence in the published literature comparing FM and internal medicine hospital medicine programs in terms of quality and patient satisfaction, our metrics at BMC remain on par with or exceed those of other general medicine services. Generating and publishing comparative outcomes should be a priority of our specialty.

Implications for Residency Training

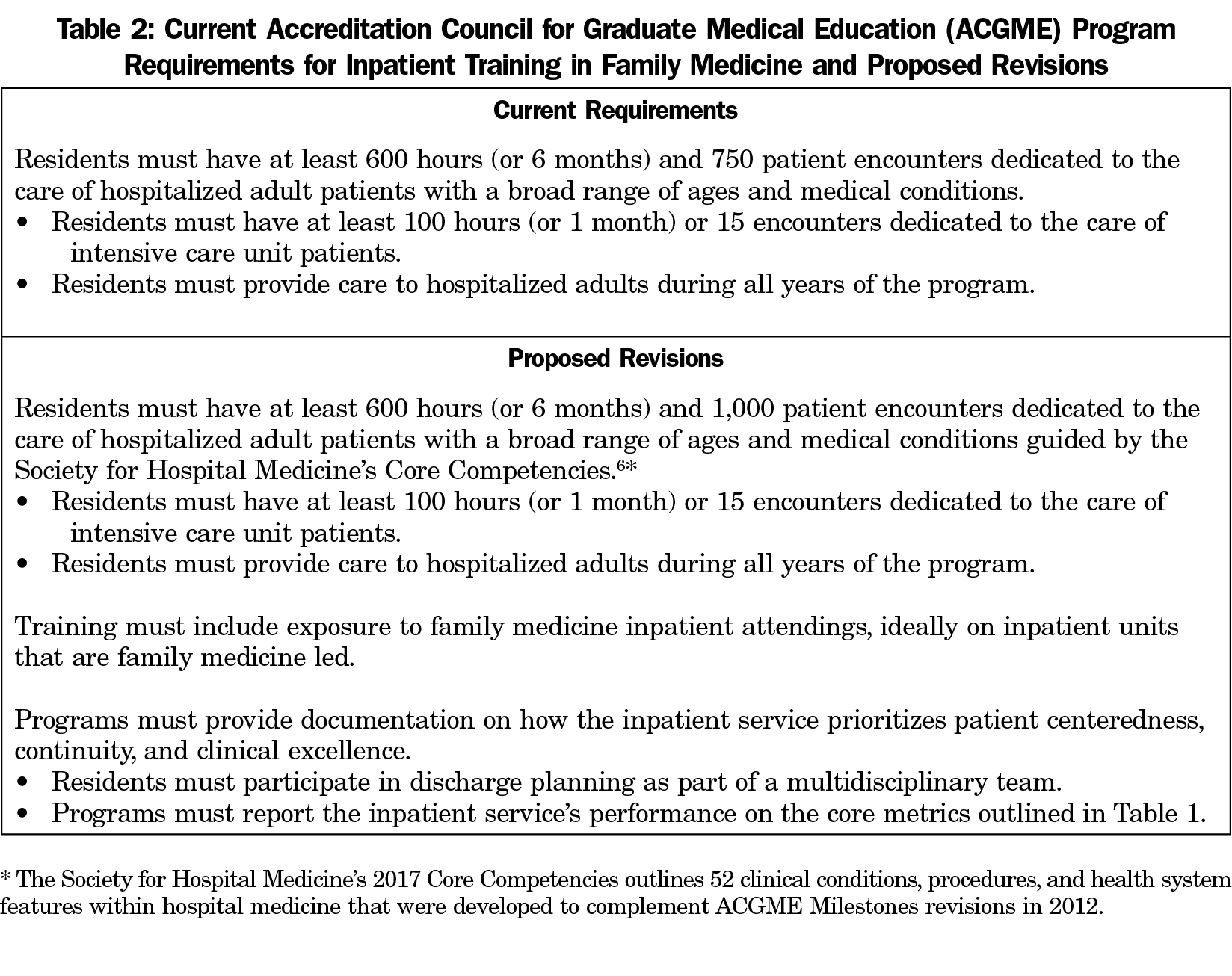

There is significant heterogeneity in the rigor of hospital medicine training in FM due to differences in clinical volume, acuity, diversity, and performance of residency program training sites. Reforming training requirements is a necessary step to expand FM’s role in hospital medicine. Table 2 presents our recommendations for revisions to the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Program Requirements for inpatient training in FM. First, given the expansion of the field of hospital medicine, we recommend that the minimum encounter requirements be increased from 750 to 1,000. By not increasing the time requirement, programs would have flexibility to determine how they can best meet the higher volume target, such as by prioritizing lower-acuity encounters as through placing residents in hospital observation units.6 Second, the ACGME should anchor the inpatient medicine competencies to the Society for Hospital Medicine 2017’s Core Competencies, which outline 52 clinical conditions, procedures, and health system features whose mastery is essential to hospital medicine, while also adding additional emphasize on continuity, patient-centeredness, and clinical excellence in line with the values of the specialty.7 In this spirit, we believe that residents should train on inpatient units that are FM-led. Our model has shown that this is feasible even at large academic medical centers where many FM programs have their residents train on internal medicine teams. These reforms would better allow classification of residency programs according to strength of inpatient training and help potential employers determine whether graduates are prepared to practice as independent hospitalists. In turn, the number of hospital medicine fellowships for FM should increase to ensure all trainees have a path to become competent hospitalists.

As the American health care system continues to careen towards uncontrollable costs, family physicians are a critical part of the delivery of hospital care and must lead efforts to smooth transitions of care, improve quality, control costs, and eliminate health disparities. We believe that the hospital care model developed at BMC can help guide other hospitals, leaders in graduate medical education, and policy makers as they look to improve health care’s future.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Dr Brian Jack for his feedback on this article.

Presentations: Content from this commentary was previoulsy presented at the National Summit on Re-Envisioning Family Medicine Residency Education, December 2020.

References

- National Center for Health Statistics. National health expenditures, average annual percent change, and percent distribution, by type of expenditure: United States, selected years 1960–2017. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Statistics-Trends-and-Reports/NationalHealthExpendData/NationalHealthAccountsHistorical.html. Published 2018 Last modified December 15, 2020. Accessed April 25, 2021.

- Kamerow DB, Wingrove P, Petterson S, Peterson L, Bazemore A. Characteristics of young family physician hospitalists. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(5):680-681. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.05.180070

- Lindenauer PK, Rothberg MB, Pekow PS, Kenwood C, Benjamin EM, Auerbach AD. Outcomes of care by hospitalists, general internists, and family physicians. N Engl J Med. 2007;357(25):2589-2600. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa067735

- Natarajan P, Ranji SR, Auerbach AD, Hauer KE. Effect of hospitalist attending physicians on trainee educational experiences: a systematic review. J Hosp Med. 2009;4(8):490-498. doi:10.1002/jhm.537

- Jack BW, Chetty VK, Anthony D, et al. A reengineered hospital discharge program to decrease rehospitalization: a randomized trial. Ann Intern Med. 2009;150(3):178-187. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-150-3-200902030-00007

- Nand B. Observationists: a unique model of training at a tertiary academic center. J Grad Med Educ. 2017;9(5):672-673. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-17-00353.1

- Nichani S, Crocker J, Fitterman N, Lukela M, eds. JHM Core Competencies 2017: Updates to the Core Competencies in Hospital Medicine. CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform; 2017.