Fifteen years ago, I was a young, passionate family physician starting my first faculty job in a residency program in Manhattan where I was going to train residents to deliver babies. I wrote “Why Pregnancy Care Should be an Essential Part of Family Medicine Training”1 during my orientation. What I wrote then still stands now:

- Some in family medicine are advocating to eliminate maternity care as a family medicine requirement due to the decline in family physicians performing deliveries and the increasing difficulties for programs to meet training requirements.

- The primary benefit of maternity care training for all family medicine residents is to produce family physicians who can provide comprehensive primary care to patients of all genders across the life spectrum.

- Training in maternity care helps to differentiate family medicine from other primary care specialties.

While working in Manhattan, I came to the realization that many people in New York City desperately needed access to high-quality, patient-centered maternity care and that those services could best be provided by family physicians working at federally-qualified health centers (FQHCs). Over the years, several residents who matched to our program ended up wanting to be trained to deliver comprehensive maternity care despite their original intentions. Now, I work at my residency alma mater: a Massachusetts FQHC that serves the needs of a community with no historical access to prenatal care until they developed their own family medicine maternity practice. Despite training in an urban setting only 25 miles from Boston, over 60% of our graduates deliver babies as part of their practice. Despite these examples of family physicians wanting to deliver high-quality, high-touch maternity care to their communities, there continues to be a decline in maternity care provision and other reproductive health services by family physicians across the United States.

What Does Society Need From Family Medicine?

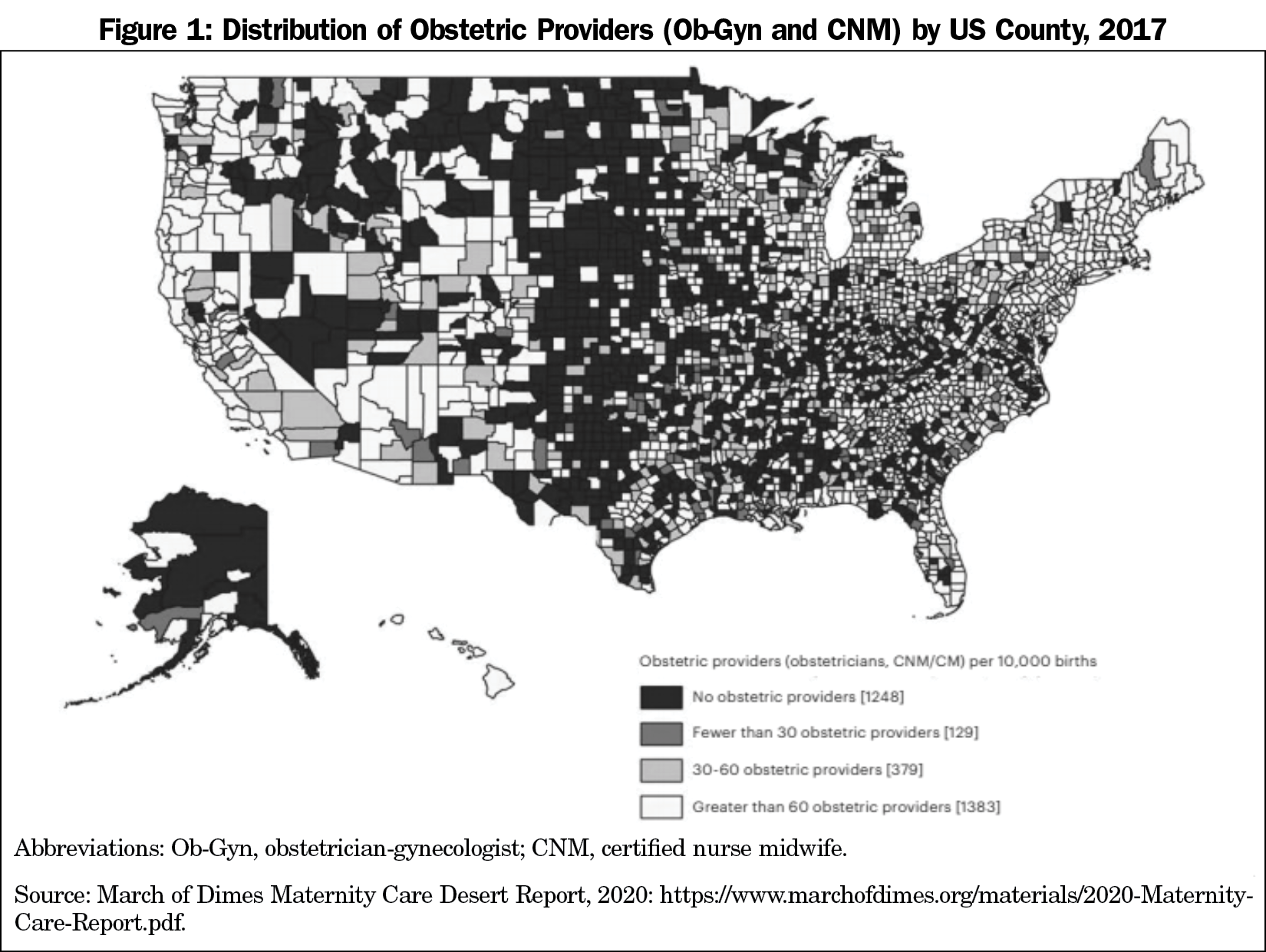

Our health care system is dysfunctional and inefficient and provides poor outcomes that are worse for women, rural Americans, and people of color. Nearly half of the counties in the United States have no obstetrician-gynecologist, leaving rural and urban underserved communities with no services (Figure 1). The United States has rising maternal mortality, which disproportionately affects rural and Black, indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC), patients. Much of this increase in maternal mortality stems from underlying physical and mental health conditions as well as structural issues including food insecurity, housing, transportation, racism, and lack of access to health care. Considering these disparities, we must ask ourselves, “who provides primary care for women?” Comprehensive primary care for women requires a physician who can care for women’s most common health needs, which includes family planning, preventive health care for cancer and cardiovascular diseases, and perinatal health care. Ideally this includes the care of children as well, as many women (especially women of color) will seek care for their children rather than themselves.2 Family medicine is poised to provide comprehensive primary care to all women and their children.

What Should We Teach and How Should We Teach It?

While many within our specialty can agree on the societal need for more family physicians to be providing comprehensive primary care for women, many program directors face structural barriers within their institutions and communities to providing the necessary training. These challenges are real, but in order to improve the health outcomes of our communities, we need to push our institutions to be part of the solution, and training regulations are a critical tool to do this.

The crux of the controversy is that programs struggle with patient and procedure volumes and with finding faculty to teach residents these skills. After the adoption of the 2014 ACGME Family Medicine Requirements (which eliminated targeted numbers of deliveries), there has been a 22% decline in deliveries performed by family medicine residents. Based on several studies,2-4 the following factors are associated with graduates including maternity care in their practices and should guide our approach to creation of evidence-based requirements:

- Caring for prenatal patients in continuity during training;

- Significant labor and delivery experience;

- Residents with more than 80 deliveries during training were significantly more likely to be performing deliveries in practice; and

- Family medicine role models training residents in maternity and newborn care.

Recommendations for ACGME Requirements

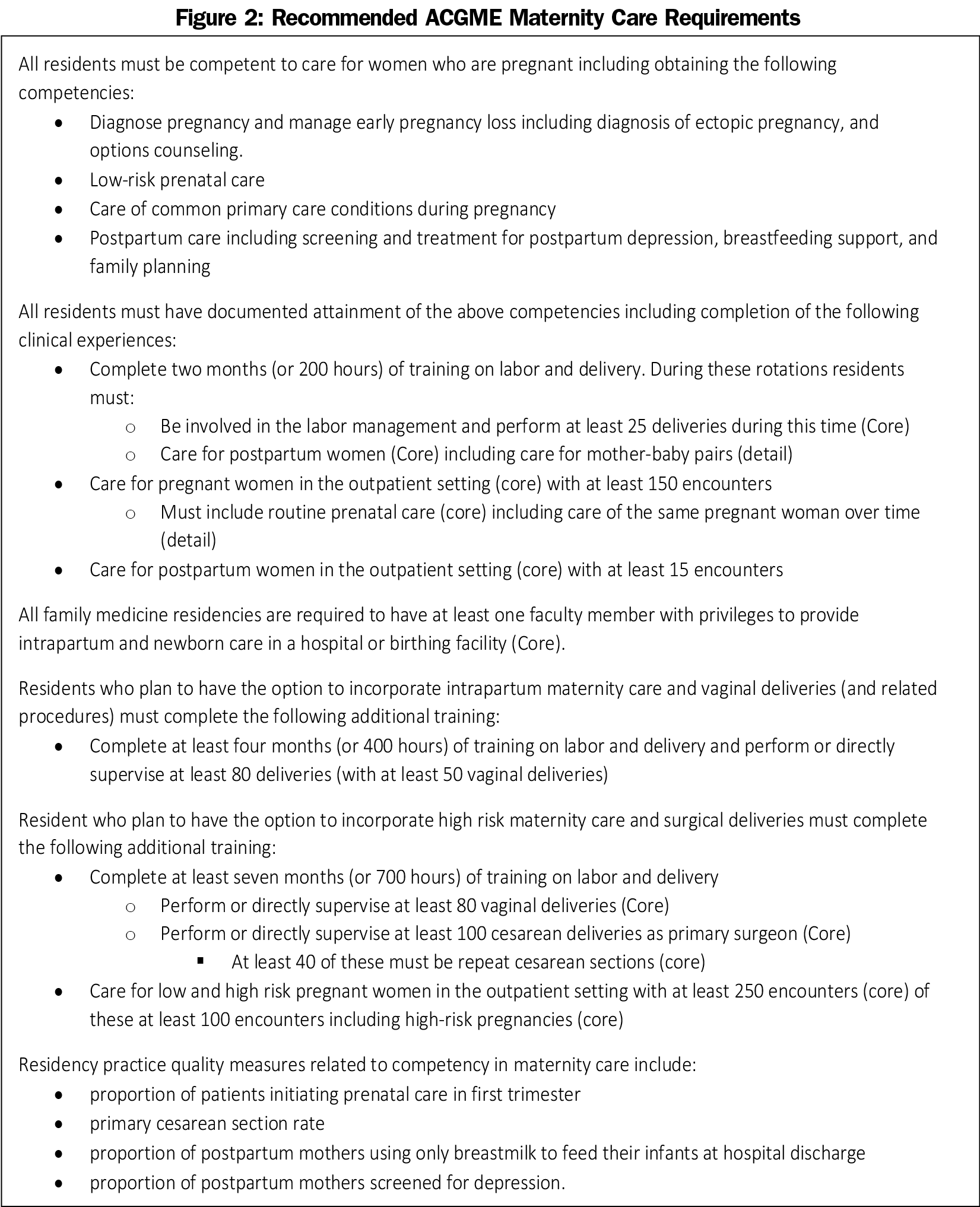

The ACGME defines the floor for the minimum training that residency programs must provide, while the American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) defines the minimal training required for individual physicians to be board certified. The idea of one minimum for the purposes of ACGME accreditation has been a barrier to the tiered training idea that has been promoted in the specialty3 and reflects somewhat the current reality. Unless the ACGME is willing to provide flexible guidelines that reflect the current uneven need for comprehensive maternity care training, we will need to use variable pathways for focused practice recognition with the ABFM5 to provide realistic training requirements for residents that will guide programs and health systems to trust in the competency of our graduates. Figure 2 gives my recommended language to the ACGME for new maternity care training requirements. Since maternity care is an essential component of women’s health, these recommendations reflect this, but also attempt to strike a balance with the reality of regional variations and emphasize training that enhances the care for all women, even if deliveries are not incorporated into future practice. I recommend minimum requirements for all programs that focus on attaining competences to care for all women in the outpatient setting, and additional requirements for enhanced training for competency in intrapartum care and surgical maternity care that would be recognized by the ABFM with focused practice recognitions. All programs have a minimum number for deliveries and are required to have a family physician with intrapartum and newborn care privileges. Such requirements protect more programs from losing their ability to provide a minimum level of training than harm the long-term accreditation of programs who cannot meet these requirements. It also holds the standard for best training based on the available evidence.

The additional training for deliveries can be integrated into residency training or as a separate fellowship. Both levels would be recognized by the ABFM with separate focused practice recognitions. It is critical that we do not require a separate fellowship for intrapartum maternity care within family medicine. This will lead to fewer family physicians meeting this need and further specialization within the discipline, at a time when our maternity deserts need family physicians with a broad scope of practice that would be narrowed if we moved to a fellowship training model.

Maternity care continues to be a defining and essential feature of our specialty. No other specialty cares for the mother-baby dyad throughout the perinatal period and no other specialty routinely provides comprehensive primary care for women. If our society and the health care system want to address the inequities in health outcomes, particularly for rural and BIPOC women, we must embrace this challenge and train the next generations of family physicians to provide this care.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: Content from this article was presented at the “Starfield IV: Reenvisioning Family Medicine Education Training” conference in December 2020.

References

- Barr WB. Why pregnancy care should be an essential part of family medicine training. Fam Med. 2005;37(5):364-366.

- Rosener SE, Barr WB, Frayne DJ, Barash JH, Gross ME, Bennett IM. Interconception care practices by family physicians at well child visits: an IMPLICIT Network study. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14(4):350-354. doi:10.1370/afm.1933

- Magee SR, Eidson-Ton WS, Leeman L, et al. Family medicine maternity care call to action: moving toward national standards for training and competency assessment. Fam Med. 2017;49(3):211-217.

- Sutter MB, Prasad R, Roberts MB, Magee SR. Teaching maternity care in family medicine residencies: what factors predict graduate continuation of obstetrics? A 2013 CERA program directors study. Fam Med. 2015;47(6):459-465.

- Biringer A, Forte M, Tobin A, Shaw E, Tannenbaum D. What influences success in family medicine maternity care education programs? Qualitative exploration. Can Fam Physician. 2018;64(5):e242-e248.

- Focused Practice Designation. American Board of Medical Specialties. https://www.abms.org/board-certification/board-certification-requirements/focused-practice-designation/. Accessed March 7, 2021.