Graduate medical education (GME) occurs during and is a crucial step of the transition between medical school and clinical practice. Residency program graduates’ abilities to provide optimal patient care, act as role models, and demonstrate excellence, compassion, professionalism, and scholarship are key elements and outcomes of successful GME programs. In order to create and maintain the training environment that leads to such outcomes, programs must continually review and revise their patient care and educational activities. Currently, compliance with accreditation standards as determined by individual specialties such as family medicine serves as a common and significant marker for program quality. Compliance with these requirements is necessary but not sufficient if faculty and residents want to achieve the goal of residency training in terms continually improving and optimizing the care they provide to their patients and communities. For overall program improvement to truly occur, the patient care, scholarship, and community activities of current residents and graduates must be assessed and used in program improvement activities. Appropriately applied to programs and using these assessments, quality improvement principles and tools have the potential to improve outcomes of patient care in residents’ current and future practice and improve programs in educating residents.

Graduate medical education (GME) occurs during and is a crucial period of physician development between medical school and clinical practice. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) highlights this period as the

“vital phase of the continuum of medical education that residents learn to provide optimal patient care under the supervision of faculty members who not only instruct, but serve as role models of excellence, compassion, professionalism, and scholarship.”1

This statement reinforces the importance of this phase of development for physicians and provides the vision for the outcome of GME: the residency program graduate providing optimal patient care in addition to acting as role models, demonstrating excellence, compassion, professionalism, and scholarship.

In order to create and maintain the training environment that leads to such outcomes, programs must continually review and revise their patient care and educational activities. The ACGME Program Requirements establish the importance and requirement of ongoing continuous improvement in residency programs, addressing practice and community needs, as well as training residents to develop competence in assessing and adjusting their professional activities. The education and use of the principles and tools of quality improvement (QI) is a potential method for use in such reviews and revisions. QI using patient, practice, and other data to improve training in GME programs is a core requirement. Appropriately applied to programs, QI has the potential to improve outcomes of patient care in the resident’s current and future practice and improve programs in educating residents.

Commonly used in the industrial sector, QI is a common sense method that manages human performance using a systematic, data-driven, and integrated approach to quality and the activity in which improvement is being sought. In health care, quality improvement is the

“combined and unceasing efforts of everyone—health care professionals, patients and their families, researchers, payers, planners and educators—to make the changes that will lead to better patient outcomes (health), better system performance (care) and better professional development (learning).”2

Current Review Process for GME

Residency programs utilize specific yet limited measures to assess the quality of training. For programs to fully utilize and experience the benefit of QI, program directors and faculty will need to increase their use of a wider range of measures and benchmarks. Currently, compliance with accreditation standards as determined by individual specialties such as family medicine serves as a common and significant marker for program quality. Compliance with these requirements is necessary, but not sufficient if faculty and residents want to achieve the goal of residency training in terms continually improving and optimizing the care they provide to their patients and communities. Requirements should be viewed as the “floor” for training and programs should seek to excel and achieve beyond them.

To ensure substantial compliance with these standards, programs have been regularly reviewed by the ACGME since its inception in 1981. Accreditation is achieved through the ACGME peer-reviewed process which has undergone revisions over the years.

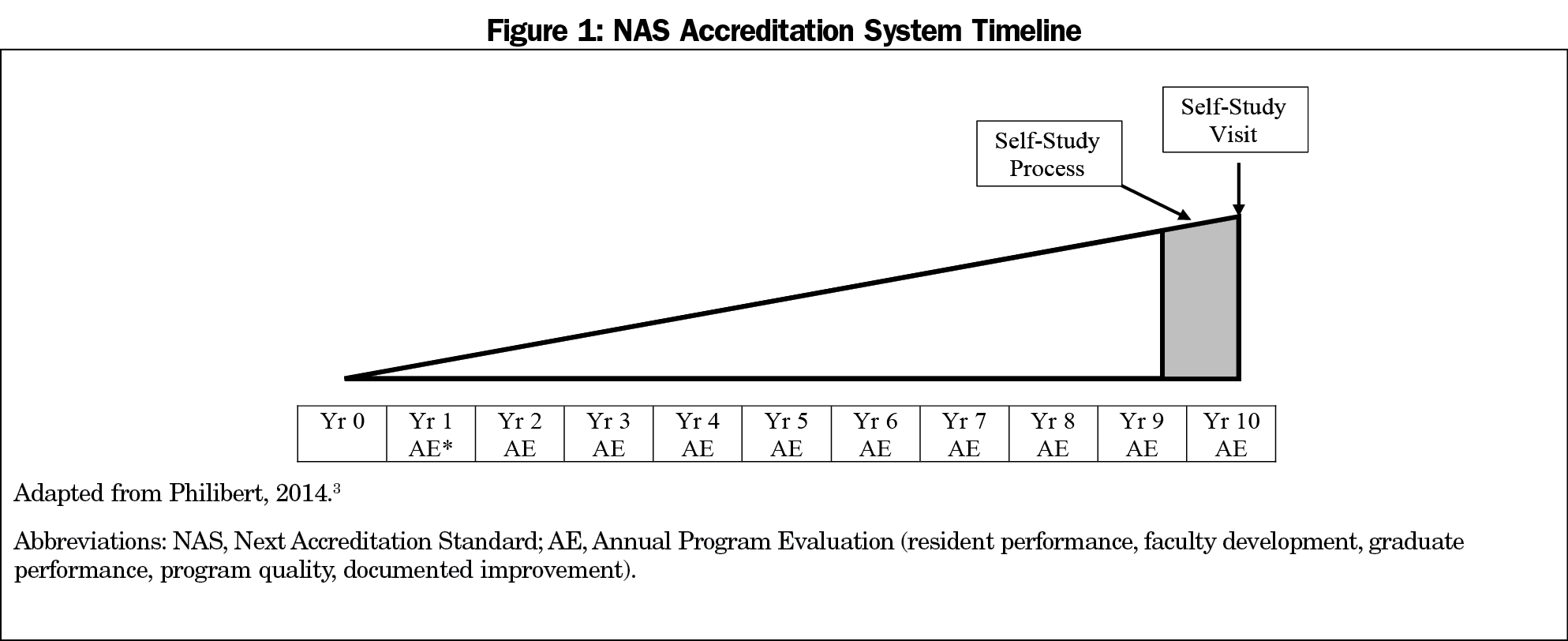

In 2014, the specialty of family medicine entered the ACGME’s Next Accreditation System (NAS; Figure 1). The NAS focuses on continuous, ongoing assessment and improvement of residency programs based upon current requirements, and moved away from the intermittent program evaluation in the prior accreditation system making ongoing program evaluation a critical component. The data used in NAS prioritizes to current program requirements, and how these requirements are being met is the standard upon which a program is assessed and accredited.

To prioritize, requirements in NAS are defined as outcome or process requirements. Process requirements are further delineated as core or detail. Programs must meet substantial compliance with program requirements to maintain continuous accreditation. Programs are reviewed annually in NAS by the ACGME Family Medicine Review Committee and evaluated for substantial compliance. Programs in continued accreditation status may choose to innovate around detail requirements. Programs must still demonstrate substantial compliance with the overarching core requirements but may choose to vary the specific methods. Critical to this approach is rigorous assessment of the innovation by the program over time and to determine whether any improvement has occurred.

Programs, particularly in family medicine, are diverse in size and structure, community, and patient demographics. As previously noted, the requirements are set as a minimum standard for all programs while encouraging flexibility to structure the program’s patient care and educational activities to meet specific resident, patient, and community needs. NAS was designed to encourage this innovation in hopes to identify evidence for best practices and thus improve future requirement iterations and generalize those best practice innovations for programs across the country.

While accreditation itself serves as a QI strategy, a self-appraisal process is critical to ongoing innovation. The Annual Program Evaluation (AE) and periodic self-study process require programs to engage with ongoing improvement beyond the accreditation decision and recommendations (Figure 1). NAS was designed so that programs will learn to be their best critics and recognize concerning trends before the ACGME Review Committee’s annual review. The AE process provides programs opportunities to recognize and address needs early on and provide reorientation towards mission and goals with response and progress before accreditation decisions are made. The self-study process culminates in a site visit. The site visit and self-study process are intended to focus on a structured improvement process, not on a punitive standard verification process, as programs seek to remain compliant with requirements. The process engages programs, program leadership, and other stakeholders in evaluating strengths and opportunities within the program. The culmination of the site visit allows evaluation of the program improvement process itself by an outside the program organization and recommendations for process and program improvement.3

To assist programs, the ACGME Accreditation Data System (WebADS) facilitates ongoing communication between the program and the ACGME. Programs are expected to maintain faculty and resident rosters, major changes, and response to citations. Annual data reporting by programs is required each summer, including patient volume, demographics, and scholarly activity. The data submitted through WebADS should be used in the QI activities in the residency program, along with other resources available.

The annual review of programs at the ACGME include the program data from WebADS as well as resident and faculty survey data, graduate board pass rates, and program history with citation response and progress reports as required. Program efforts in continuous program evaluation have been described in various specialties.4,5 Further study of program QI through the NAS are needed, especially to determine whether improvements are being made and requirements not annually monitored are being met.

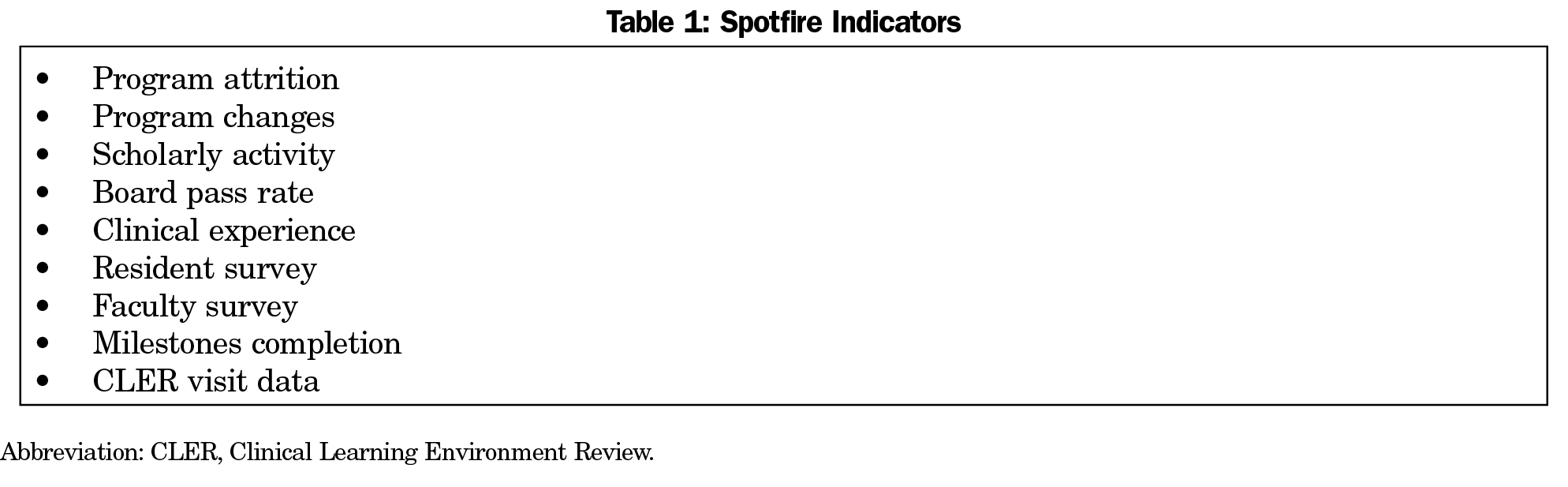

Integral to the NAS and the process described above, the ACGME uses the submitted program data in Web ADS to identify programs that may be at risk of not meeting requirements that could lead to a negative action against the program. This annual data review is processed first through a data analysis program termed “Spotfire.” The measures used were identified through modeling of what data previously identified programs with short-cycle reviews and what data were most important to individual review committees (Table 1). Thresholds are set to bring these at-risk programs for further review by the committee. Program citations and areas for improvement are identified solely by committee review. The NAS is meant to both identify struggling programs early, and to encourage programs that are doing well to innovate and develop best practices. The ability of this system to use the limited Spotfire measures to predict success of a program on the more in-depth self-study visit or if an improvement in residency training has occurred in not known.

Despite a vast majority of programs meeting substantial compliance with requirements as reflected in a high rate of accreditation, this compliance does not appear to meaningfully translate to residents and faculty based upon the results of a recent survey.6 For instance, a core requirement is that “residents and faculty members must receive data on quality metrics and benchmarks related to their patient populations.”1 The recent American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM) survey found that a “large majority of residents did not know their panel size.” Furthermore, “about half reported getting feedback on quality or access for their panel of patients, and very few have received feedback on cost or utilization of care for their panel of patients.”3

Compliance with requirements also appears to be poorly translated to faculty as well. In the same ABFM survey, faculty noted the “frequent lack of information about panel size, lack of feedback about quality, access and cost and the relative rarity of patient advisory committees.”6 Of particular note, “almost 70% reported that residents received no systematic feedback on cost of care or referral appropriateness.” As providing optimal and high-quality patient care is a major outcome of residency training, these findings reflect a missed opportunity to emphasize, address, and review the use of patient quality of care measures in residency training.

Finally, compliance with requirements on a program level achieves accreditation and places that program on par with other accredited programs. One could argue that the incentive for programs to excel in any current requirement or to innovate in some manner are neither clearly delineated nor systemically recognized.

Additional levels of supervision and monitoring are present to assist and augment the work done on the programmatic level. The sponsoring institution provides oversight of programs as well through the graduate medical education committee (GMEC). The GMEC provides oversight of learning and working environment as well as of the quality of educational experiences in associated residency programs. The GMEC and sponsoring institution are expected to work with and monitor programs and their improvement activities.

As a key component of the NAS, the ACGME established the Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) program. The aim of this program is to promote safety and quality of care by focusing on six areas important to the safety and quality of care in teaching hospitals and the care residents will provide in a lifetime of practice after completion of training.7 The six areas encompass engagement of residents in patient safety, quality improvement and care transitions, promoting appropriate resident supervision, duty hour oversight and fatigue management, and enhancing professionalism. The impact of this program on specific residency training in particular family medicine is not yet well studied.

Residency Program Assessment and Improvement: Additional Measures are Needed

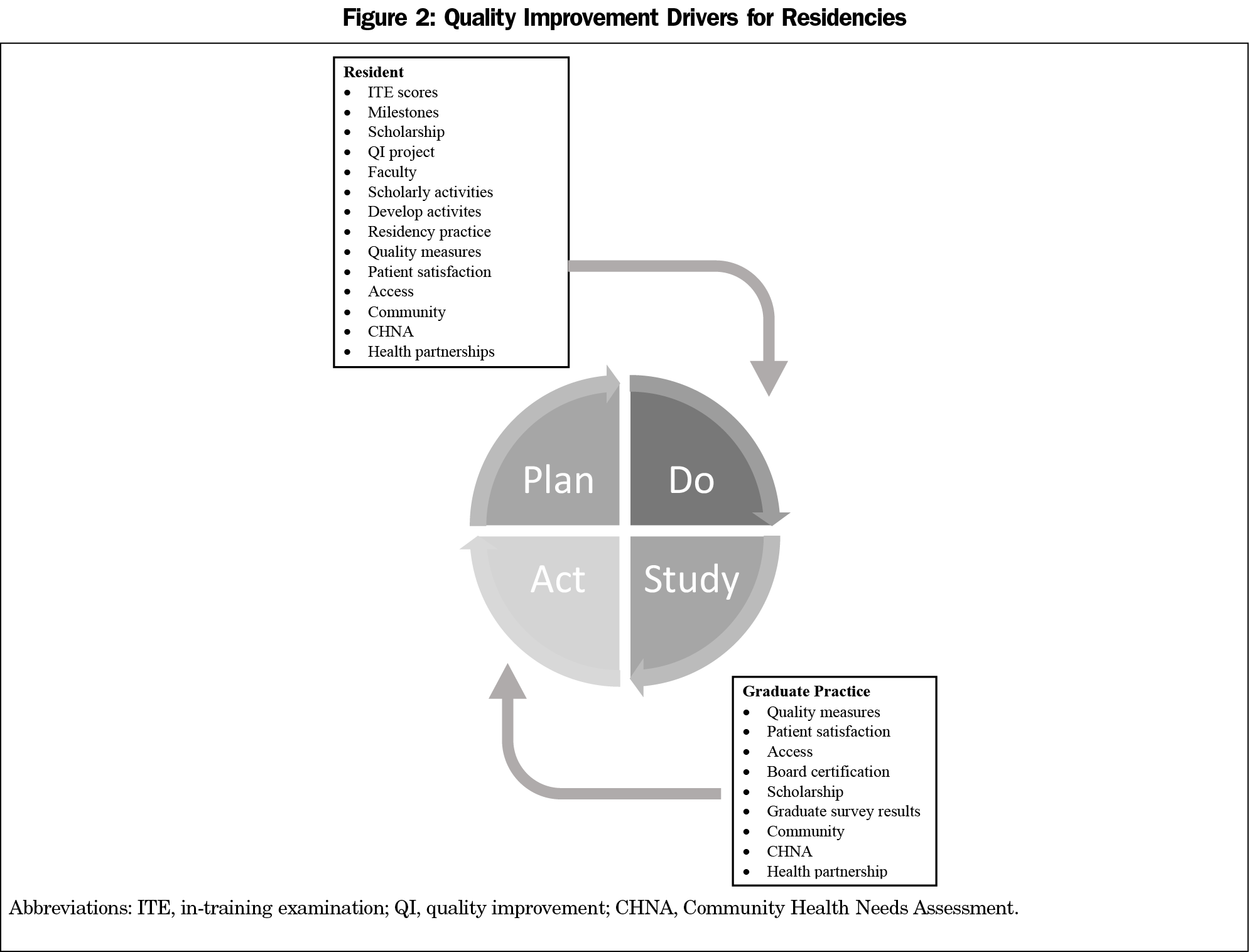

For residency programs to achieve their full mission and social responsibility of training residents for their current and future practices, four components of the training environment need to be used to assess and improve the overall quality of the program: resident education, faculty development, clinical practice, and community (Figure 2). In addition and just as vital as using data from the residency program, the practice and community activities of the program graduates need to be assessed and used to further enhance the residency training environment. Both the current activities of the residency program and the activities of program graduates must be used in the QI plan-do-study-act cycles used in program improvement.

Resident education is fundamental to GME and needs to include assessments of knowledge, skills, and performance. The ACGME developed milestones for the formative and developmental improvement of individual learners and the ongoing development and continuous quality improvement of the education programs and specialty. The milestones evaluation system provides a roadmap for continuous improvement and development of individual learners’ knowledge and skills. Longitudinal milestone ratings provide educationally useful, predictive information to help individual residents address potential gaps.8 Assessment of performance in terms of specific quality of care metrics are not as well integrated into the overall evaluations of residents and their use in an overall evaluation is vital. These quality of care metrics should also be part of the overall program evaluation and serve as an example for the residents of both personal and team-based activity assessment.

The second component of the program for use in ongoing improvement necessary for high quality residency training is faculty development. Faculty development in QI and how to use its principles and tools to enhance resident education and patient care appears underdeveloped. Specifically, a major and common challenge to training residents in QI is the availability of faculty with the expertise to teach and mentor QI curricular initiatives.9 Faculty are key contributors to resident knowledge of QI, and this role modeling will engage learners in the process as well.

The third component of ongoing improvement is the clinical practice of the residency program. The program must provide residents and faculty members data on quality metrics and benchmarks related to their patient populations. This information should be included in interprofessional QI activities and should be regularly monitored so as to evaluate the success of any improvement efforts. Initiatives and activities such as patient and family advocacy committees must provide input to the practice efforts in improvement to provide patient-centered approaches to education and care.

The health of communities around the residency program is another component for use in improvement activities. The formal community needs assessments such as the Community Health Needs Assessment (CHNA) must provide input for practice settings to drive the residency to serve the specific needs of the community and larger populations. Community needs and outcomes can serve as additional measurements of program effectiveness.

For example, the University of Florida Department of Community Health and Family Medicine used geocoding to determine hotspots for hospital readmissions. This information was used in a QI project that lead to a significant decrease in the readmission rate to an inpatient family medicine team.10

For overall program improvement to truly occur, the patient care, scholarship, and community activities of graduates need to be assessed and used in program improvement activities. Currently programs are only required to monitor board pass and certification rates of graduates. Feedback from a program’s graduates is vital feedback for program improvement. Currently the ABFM conducts a survey of graduates of family medicine residency programs and this information has been used in several studies. If and how these data are used by individual programs is not well studied. Graduate surveys conducted by numerous family medicine residency programs have provided invaluable information and assessment about the work and activities of these graduates.11

Going Forward–Recommendations for the Future of Residency Training

As recently noted by members of the ABFM,

“We must construct a system of family medicine residency education across the country that will more successfully and continually adapt to the needs of society and improve outcomes of care and education while preserving the enduring core of knowledge, skills, and attitudes essential to the practice of family medicine.”13

More succinctly, “family physicians leave residencies equipped to address these problems and lead the changes society needs in health and health care.” The benchmarks we use to evaluate and improve family medicine residencies go beyond compliance with ACGME requirements and must include practice and community activities of family physicians as well as specific patient care and community health outcomes.

In family medicine, as in other disciplines, the markers or measures of a high-quality residency training program and the outcomes that training produces in graduates are not clearly and consistently defined nor agreed upon. For family medicine residency programs, these measures should continue to use compliance with ACGME requirements. Though these requirements currently include addressing the health care needs of the greater community served by program and sponsoring institution, specific measures need to be included in the revised requirement language so as to be used as a benchmark for success in this area. For instance, the measures of requirement compliance and program quality should include an assessment regarding community health, such as the CHNA. Programs should be required to explain how they use community-oriented data to address specific health care needs noted in the practice and surrounding community.

To highlight the importance of patient care during residency training, resident and residency-specific quality of care measures need to be reviewed and used as an evaluation tool. For instance, each resident and faculty should know their compliance with the following measures as the reflect significant heath care issues and problems for our country: rate of tobacco use, blood pressure control in patients with hypertension, lifestyle activities (particularly diet and exercise pattern) of patients, blood sugar control in patients with diabetes mellitus, depression screening, alcohol and other substance of abuse screening, and immunization status. These statistics should be included in the annual program evaluation and the current results and benchmarks the program is using for improvement should be included.

Furthermore, measures of a residency program graduate beyond the training period needs to be included in the overall assessment and improvement activities of a residency program. The ABFM graduate survey is an important tool in this area.12 This tool has been used in the literature to further assess family medicine residency training.10 The discipline needs to go beyond this graduate survey and include patient quality of care measures, patient satisfaction surveys, and community activities of graduates.

In summary, the principles and tools of QI can be valuable as the discipline of family medicine seeks to continually improve residency training and provide our society with family physicians who meet the needs of patients and communities. To do so, meeting ACGME program requirements is necessary, but not sufficient. Our discipline needs to expand the measures and benchmarks we use to assess programs and provide the support needed for the programs to improve to meet the health care needs of a diverse and growing population.

References

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common Program Requirements. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency2020.pdf. Accessed February 19, 2021

- Batalden PB, Davidoff F. What is “quality improvement” and how can it transform healthcare? Qual Saf Health Care. 2007;16(1):2-3. doi:10.1136/qshc.2006.022046

- Philibert I, Lieh-Lai M. A practical guide to the ACGME Self-Study. J Grad Med Educ. 2014;6(3):612-614. doi:10.4300/JGME-06-03-55

- Kraut A, Tillman D, Barclay-Buchanan C, et al. The Continuous Residency Improvement Committee (CRIC) – A novel twist for program evaluation in an academic emergency medicine residency program. JETem. 2018;3(3):I1-I26.

- Wiemers M, Nadeau M, Tysinger J, Fernandez Falcon C. Annual program review process: an enhanced process with outcomes. Med Educ Online. 2018;23(1):1527626. doi:10.1080/10872981.2018.1527626

- American Board of Family Medicine. Starfield Summit IV: Re-envisioning Family Medicine Residency Education. https://residency.starfieldsummit.com/library. Accessed April 18, 2021.

- Weiss KB, Wagner R, Nasca TJ. Development, testing, and implementation of the ACGME Clinical Learning Environment Review (CLER) program. J Grad Med Educ. 2012;4(3):396-398. doi:10.4300/JGME-04-03-31

- Holmboe ES, Yamazaki K, Nasca TJ, Hamstra SJ. Using longitudinal milestones data and learning analytics to facilitate the professional development of residents: early lessons from three specialties. Acad Med. 2020;95(1):97-103. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002899

- Wong BM, Goldman J, Goguen JM, et al. Faculty-Resident “Co-learning”: A longitudinal exploration of an innovative model for faculty development in quality improvement. Acad Med. 2017;92(8):1151-1159. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001505

- Carek PJ, Mims L, Kirkpatrick S, et al. Does community or university-based residency sponsorship affect graduate perceived preparation or performance? J Grad Med Educ. 2020;12(5):583-590. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-19-00907.1

- Carek PJ, Malaty J, Dietrich E, et al. Addressing hospital readmissions: impact of weekly review. Fam Med. 2016;48(8):638-641.

- American Board of Family Medicine. 2019 Graduate Survey Report. https://www.theabfm.org/sites/default/files/PDF/NationalOnlyReport2019.pdf. Accessed April 19, 2021.

- Newton WP, Magill M, Biggs W, et al. Re-envisioning family medicine residencies: the end in mind. J Am Board Fam Med. 2021;34(1):246-248. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2021.01.200604

There are no comments for this article.