From our beginnings we understood the need to address behavioral health concerns as a normal part of primary care, and so required behavioral scientists in each program’s core faculty. This was a great first step, but we know more now, and are long overdue for an overhaul of our behavioral curriculum.

What is behavioral health? Here we follow the shorthand convention established by the Joint Principles Working Party1 that includes attention to (1) symptoms of psychosocial distress that cause functional impairment; (2) psychological symptoms and psychiatric disorders; (3) substance use disorders; and (4) health behavior change.

We know that when the primary care we offer patients is comprehensive, addressing most of their health concerns, it produces better outcomes.2 No single gesture more greatly expands comprehensiveness in primary care than routinely including patients’ behavioral health concerns. We also know that every problem and concern we see in family medicine has a behavioral dimension.

Two principles of human health bear on this update. The first is the indivisibility of the behavioral and the physical, neither of which can be understood or managed apart from the other. Attempts to do so will fail, resulting in inferior care. This is no longer a controversial proposition,3 but we often practice and teach as if this were not true. The so-called physical and the so-called psychological coexist, each only with the other. The subject of our health ministrations is the person, the whole person, in whom any disease or disorder is embedded, not merely the disease or disorder itself.

This does not mean we should stop treating illnesses in our patients. Learning to identify and manage diseases is a precondition for competence as a primary care clinician, but it is only a precondition. Our usual family medicine patient has a set of health concerns consisting of five or six active problems, previous experiences with these problems, preferences, opinions, convictions, habits, strengths, fears, family issues, cultural contexts, personal difficulties, and so on. Our therapeutic approach must be toward that entire complex, toward a comprehensive personal care plan, and not just the diagnoses that can be pulled from it. We cannot win health one disease at a time. That said, a number of common behavioral conditions such as depression, generalized anxiety disorder, or postraumatic stress disorder warrant disease-specific mastery. These conditions fit into the disease-specific curriculum alongside such diseases as type 2 diabetes, asthma, and osteoarthritis.

The second principle is the biopsychosocial model, formulated by George Engel in 1977.4 This model threads through family medicine literature and curricula, but too often we have ignored its implications in practice. This model stands against the biomedical model, which reduces diseases to organ dysfunction, intracellular disturbances, and molecular or genetic derangements. Engel taught us that this biomedical approach only accounts for a fraction of the factors that affect health, whereas psychosocial factors—our thoughts, our feelings, our beliefs, the supportiveness or toxicity of our social networks, our education, our income, our race, our gender, and so on—these psychosocial factors actually account for most of the variation in our health. We will not be fully effective in family medicine until we ground ourselves in the biopsychosocial, at the nexus where all health vectors converge—how relationships affect immune function, how poverty and racial bias affect mortality, how physician communication affects patient satisfaction and adherence, and so on.5

Adopting the biopsychosocial model makes us more effective, but it is more difficult, consisting as it does of so many more variables to account for. More difficult, that is, until we learn to practice in teams. Team-based primary care is no longer controversial as a general proposition,6 but we have been careless about how we understand, constitute, and operate teams. If we accept the evidence regarding the advantages of addressing most or all of a patient’s health concerns, that most patients have behavioral health concerns, and that behavioral health concerns are inextricably intertwined with all other health concerns, then it follows that embedded, integrated behavioral clinicians must be core members of the primary care team—clinicians such as psychologists or social workers or psychiatrists or psychiatric nurse clinicians or others. Regardless of discipline, these clinicians must understand the pace and workflow of primary care, the common behavioral issues that arise in this setting, and the principles of team-based care. Team members work together with the patient to formulate, operate, monitor, and adjust the patient’s personal care plan. They do this together, by such means as care team meetings, sharing a common medical record, regularly negotiating the best next steps in patients’ care, and otherwise jointly taking responsibility for the patient’s health.

The constitution and operation of teams consisting of coequal partners in the care process is known as integrated care. There are a number of models of integrated care. The most extensively studied is the Collaborative Care Model (CCM), initially developed to deal with depression in the elderly, but later extended to other age groups and other mental disorders comorbid with chronic medical conditions. The CCM uses a psychiatrist consultant and a social worker or nurse care manager who finds patients through the use of the PHQ-9. The care manager and the primary care clinician, with consultation from the psychiatrist, then provide treatment for the patient. This model is supported with solid evidence of effectiveness and cost-effectiveness from many randomized clinical trials.7 The CCM has significant real-world limitations and has not sustained well as a stand-alone model with general use in the field. It’s great for dealing with single problems such as depression, or anxiety, or even depression plus diabetes, but it is not the kind of integrated team that is capable of responding to the wide, unpredictable range of behavioral concerns necessary when rendering whole-person care.

A more broad and widely deployed model is Integrated Behavioral Health (IBH). The evidence for its effectiveness is less compelling than that for the CCM because this model is more difficult to evaluate, but high-fidelity evaluations are beginning to appear in the literature.8 This model has enjoyed explosive growth in primary care in recent years because of its flexibility and sustainability—and complementarity to the CCM model when appropriate. Some version of this team-based model will likely become the norm for advanced primary care practices in the United States. The continuity clinics of all family medicine residencies should support team-based care of this kind.

It is fair to say that the continuity practice is itself the heart of the curriculum for educating family physicians. This model of practice should be characterized by team-based care, but also by attention to most or all health concerns, an adaptive capacity to deal with unanticipated problems, a commitment to continually improving workflows, care processes, and health outcomes, and by embedding in the communities in which our patients live. Prototypes and working models for this kind of practice are in the field today.9

Finally, we must realize that our responsibility is not merely to prepare family physicians to address their patients’ health concerns in an integrated, team-based way, but ultimately to prepare the primary care workforce, including behavioral health clinicians. A behavioral clinician can only learn how to function as a primary care clinician in a primary care setting; there is literally nowhere else in the world to learn this. It thus follows that residency programs must train residents with strong identities as family physicians but also create an interprofessional training ground to prepare primary care teams.10 This is essential if primary care is to be the foundation of our country’s health care, to truly advance the health of our people.

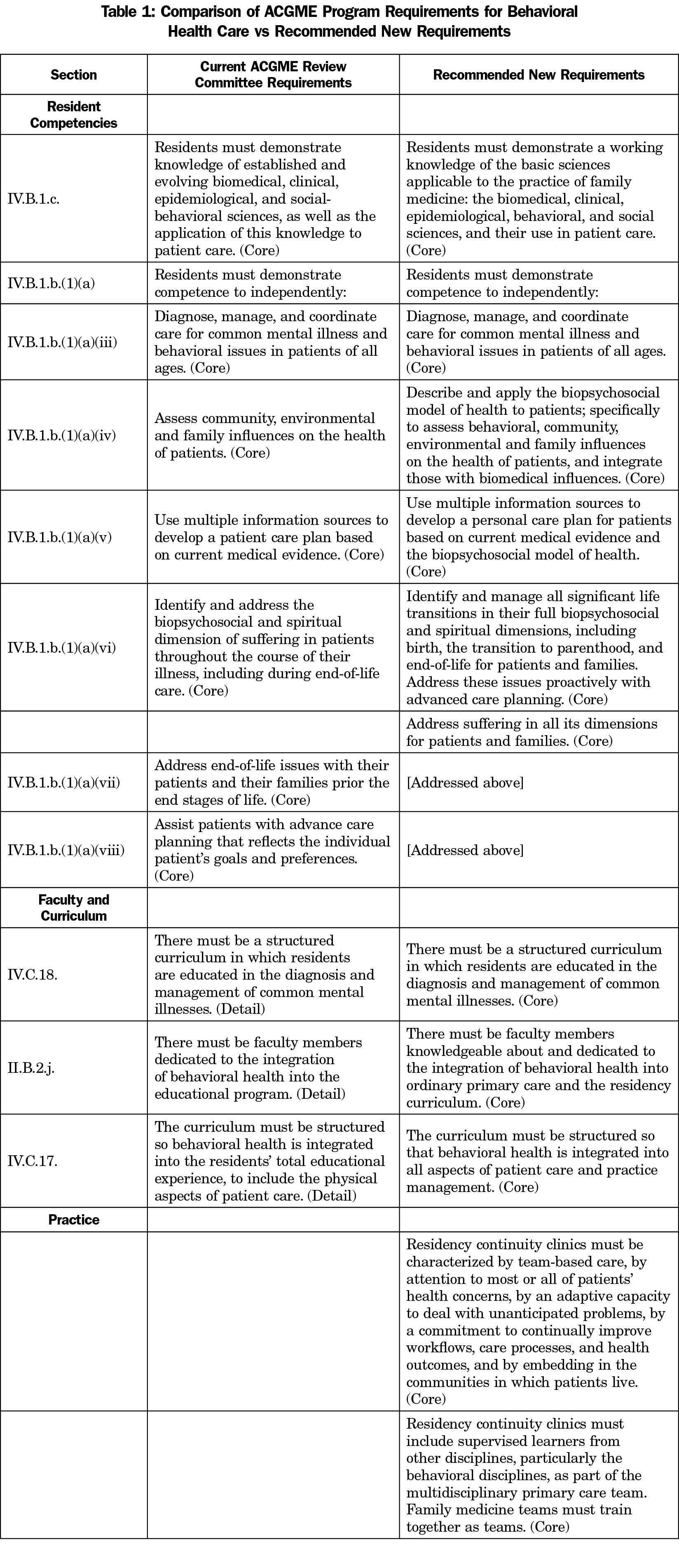

What does all this say about how we prepare residents for practice? Table 1 outlines the current ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine, their curriculum, and their practices, and contrasts these with recommendations for new core requirements that comport with contemporary evidence and best practices. These recommendations are within the reach of all existing residency programs. Should these recommendations become our new baseline requirements, we would almost immediately enjoy an improvement in physician satisfaction and the quality and effectiveness of the practice of family medicine in the United States.