Professionalism is the basis of medicine’s contract with society. It demands placing the interests of patients above those of the physician, setting and maintaining standards of competence and integrity, and providing expert advice to society on matters of health.1

Thus states the ABFM Guidelines for Professionalism, Licensure, and Personal Conduct. However, the new health care environment poses new professionalism challenges. The last 20 years has seen a shift toward corporate medicine, with most family physicians employed by an organization. The result has been a loss of autonomy and an increase in dual agency, in which physicians are tasked with upholding the best interests of patients while also meeting the financial goals of the institution. As we consider how best to assure that family medicine residency programs facilitate the development and further inculcate traditional qualities of professionalism, it is clearly necessary to recognize the shortcomings of such definitions—and current Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) program requirements—and create an approach to professionalism that best serves the public and recognizes the physician and the patient are no longer the only stakeholders in the room.

Professionalism requirements must also reflect, however, the effect of idealized projections of professionalism on physician well-being. There is a demonstrable risk of exploitation of physicians by organizations, that rely on physician professionalism to meet corporate goals2 while at the same time diminish the physician’s ability to navigate the four classic principles of medical ethics: patient autonomy, beneficence, nonmaleficence, and justice. We therefore need to develop new educational and evaluation strategies and then standardize their implementation using our specialty’s next generation of ACGME program requirements.

How Has the Modern Dialogue Developed?

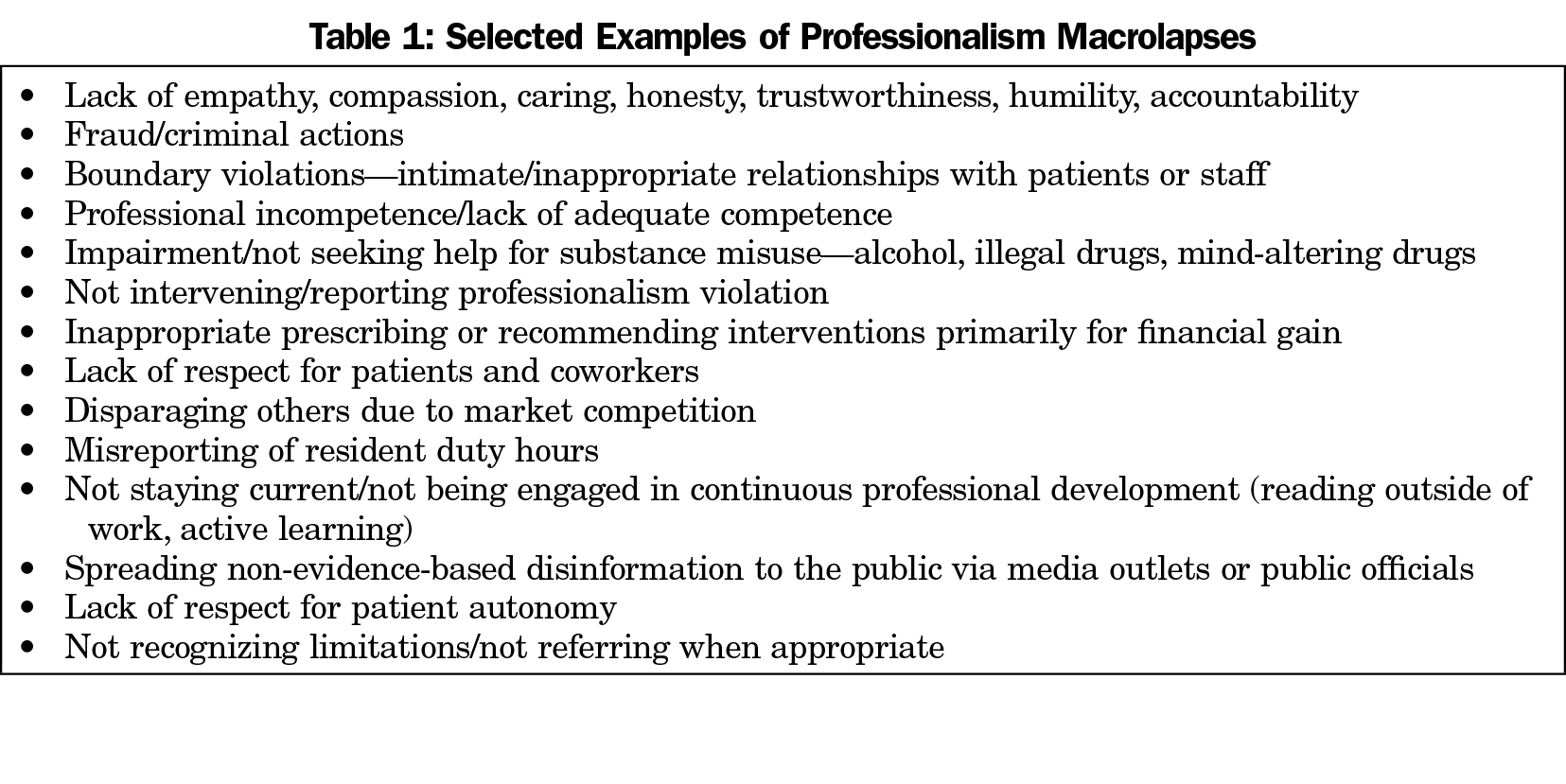

Traditional professionalism definitions are typically a list of prohibited behaviors, rather than aspirational concepts or positive exemplars, and assume an autonomous physician in medical practice. These “macrolapses” (Table 1) are typically addressed well in traditional professionalism training, are covered by existing codes of ethics, are individual-focused, and when present often lead to licensure or board sanctions.

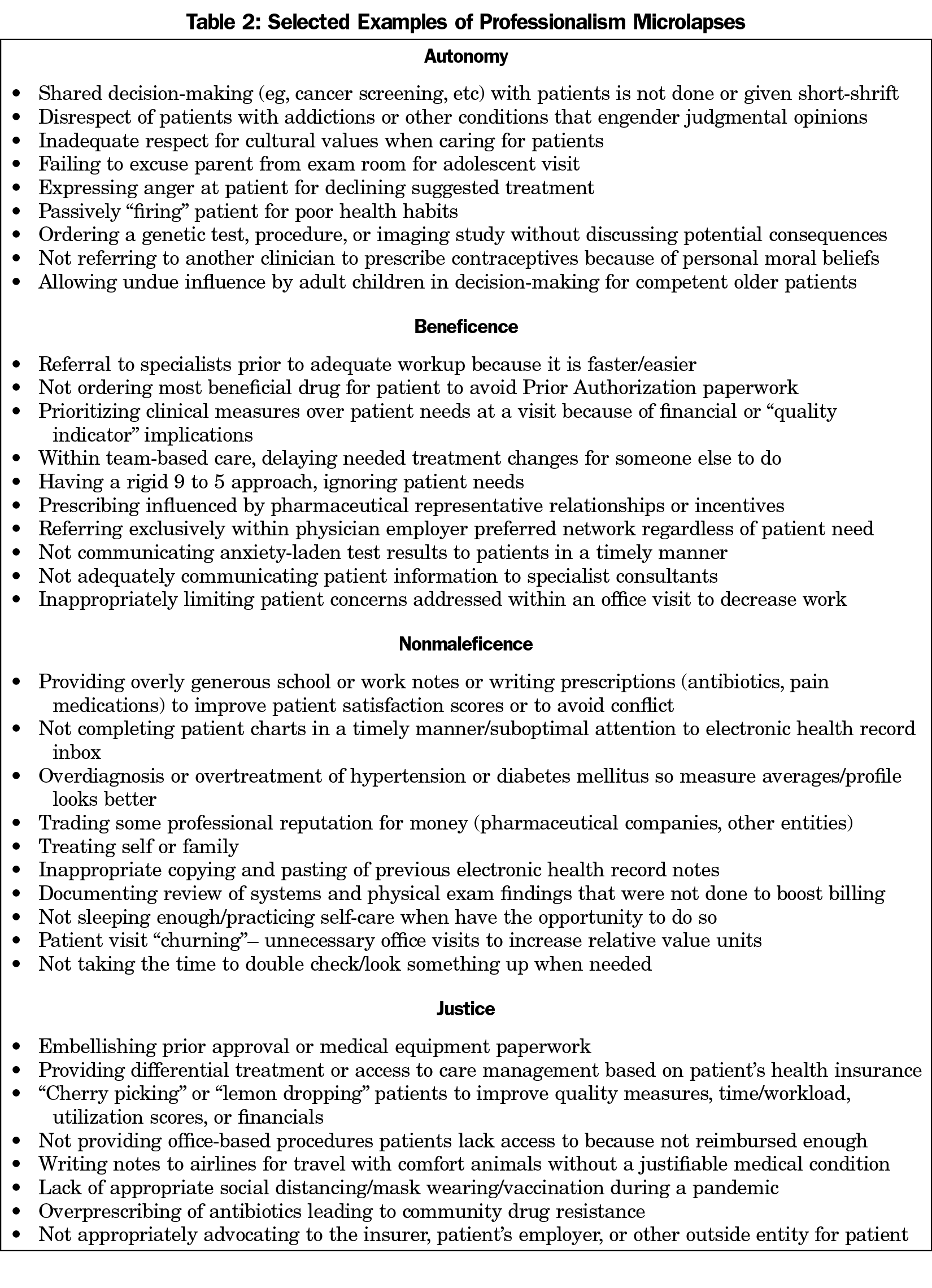

Institutions, rather than peers, increasingly police professionalism to identify and address these unprofessional behaviors. However, the erosion of professional autonomy requires reexamining and redefining professionalism on a more granular level. In family medicine, comprehensive care, first-contact care, coordination of care, and continuity of care—the pillars of effective primary care—are sailing on a windswept sea of corporatization, consolidation, consumerism, and commercialization that promotes transactional rather than relationship-based care. Relationship-based care may be becoming more and more difficult for the public to actually obtain. As a result, repetitive, insidious microlapses (Table 2) are much more common, are often ignored and typically missed in training, go undetected in practice, and yet collectively may harm patients at least as much as macrolapses.

These microlapses result from daily, repetitive, under-the-radar, often unobserved microtraumas—the slings and arrows of current primary care practice that are more like repetitive strain injuries than an acute fracture. Faced with a multitude of tasks without the time to perform them, residents create self-protective shortcuts to navigate these simultaneous and conflicting demands, often resulting from the dual agency of trying to serve the patient, the employer, and/or the insurer. Like football players’ chronic traumatic encephalopathy, microtraumas occurring in daily practice often lead to a sort of “chronic traumatic deprofessionalization” characterized by professionalism microlapses, and in severe cases, macrolapses.

We are still training residents in professionalism as if medicine was baseball, a team sport but largely based on individual successes or failures in a pastoral atmosphere with no clock. Instead, clinical practice needs to be envisioned as aligning with football, another team sport with important individual actions, but in which success is largely based on collective, coordinated actions in a microtraumatic, time-pressured atmosphere. We are currently training residents for the wrong sport.

Where Should Professionalism Fit in Residency Education?

Residencies need to improve sentinel reporting systems (as is done for patient safety) during precepting supervision to identify the inevitable formative microlapses of each resident rather than focusing mostly on judging macrolapses committed by “bad apples.” A safe learning environment and trust are essential in making this successful.

Similarly, microacts of professionalism need to be better surfaced for positive reinforcement and peer role modeling. Making the extra phone call to a patient, going the extra mile covering call for a peer when needed, and other similar actions must be more consistently identified and reinforced. Required 360-degree reviews, reflective writing, and guided discussions could all contribute to this.

Professionalism expectations should also clearly state what to exclude, such as whether physicians are responsible or should be held accountable for addressing social determinants of health (SDH) when not provided the resources to do so.3 Defining corporate health care systems’, insurers’, and government’s potentially distinguishable primary accountabilities in this area would better serve the public than ascribing SDH-driven clinical measures to individual physicians or their practices.

While didactic teaching sessions can be used to explore the philosophical concepts of professionalism and to convey the traditional “don’ts,” teaching cannot be “do as I say, not as I do.” Professional behavior, leading to the formation of a professional identity, is best taught daily through role modeling, guided actions, and feedback, with particular emphasis on developing reflective clinical practice.4 These approaches require an attention to the culture that undergirds each residency’s community of practice, which should include an atmosphere of inquiry, leadership by example, and opportunity for discussion and individual reflection. Family medicine’s own unique identity helps form and exists in parallel with the resident’s individual professional identity.5

Although helpful to consider as a discrete competency to highlight its importance, professionalism underlies and is interwoven within the other five ACGME general competencies. Residency milestones are inherently a professionalism-based construct. These milestones also role model continuous professional development, self-assessment, and openness to feedback as necessary long beyond residency.

The task of professional identity formation (especially in the last 2 years of medical school and first year of residency) is often one of idealism colliding with the realities of health care environments. Residents must navigate and reconcile the world of what should be with the world as it is. Assessment of how well or poorly this is navigated is notoriously difficult without universally-accepted tools. Opportunities for guided reflection, both on an individual and team/class level, are necessary.

Specific Suggestions for the Family Medicine Review Committee

Although professionalism is the foundation upon which all other general competencies are built, current ACGME program requirements in this area are limited. Over the past decade, interest in professionalism at the undergraduate medical education level, including Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME) standards6 for medical schools’ teaching of professionalism, has not been matched at the graduate medical education level. Notably, LCME requirements include promoting positive acts of professionalism. Revised ACGME requirements should likewise further emphasize the learning environment for residents working in a dual agency health system, particularly if professionalism is recognized as a necessary mitigating force for the public’s benefit against the excesses of unrelenting corporatization.

The basic tenets to advance family medicine GME training in professionalism are (1) the need for an explicit curriculum with intentional optimization of faculty role modeling and faculty development in this area; (2) recognition and discussion of microlapses and microacts, together with a system of identifying and tracking in a safe community of practice; and (3) engineering such that these occur without significant added resource utilization, including faculty and resident time.

Balint groups are focused on the interpersonal aspects of working with patients to better understand patient and physician feelings. Cruess’ formulation of professionalism7—that it is a combination of ethical beliefs, specific behaviors and development of professional/specialty identity—are often somewhat tangentially and unintentionally explored in residency Balint sessions, but many programs do not require attendance nor offer them. Balint-like professionalism group sessions should be required. Reflective practice needs to become a more explicit part of required curriculum, through narrative medicine, group case-based sessions, advisor-advisee meetings, and perhaps most importantly, in clinical precepting sessions. Professionalism challenges for residents are often currently not adequately identified nor discussed in a hurried, time-compressed learning environment that devolves to ethically unexamined shortcuts and working at a transactional level.

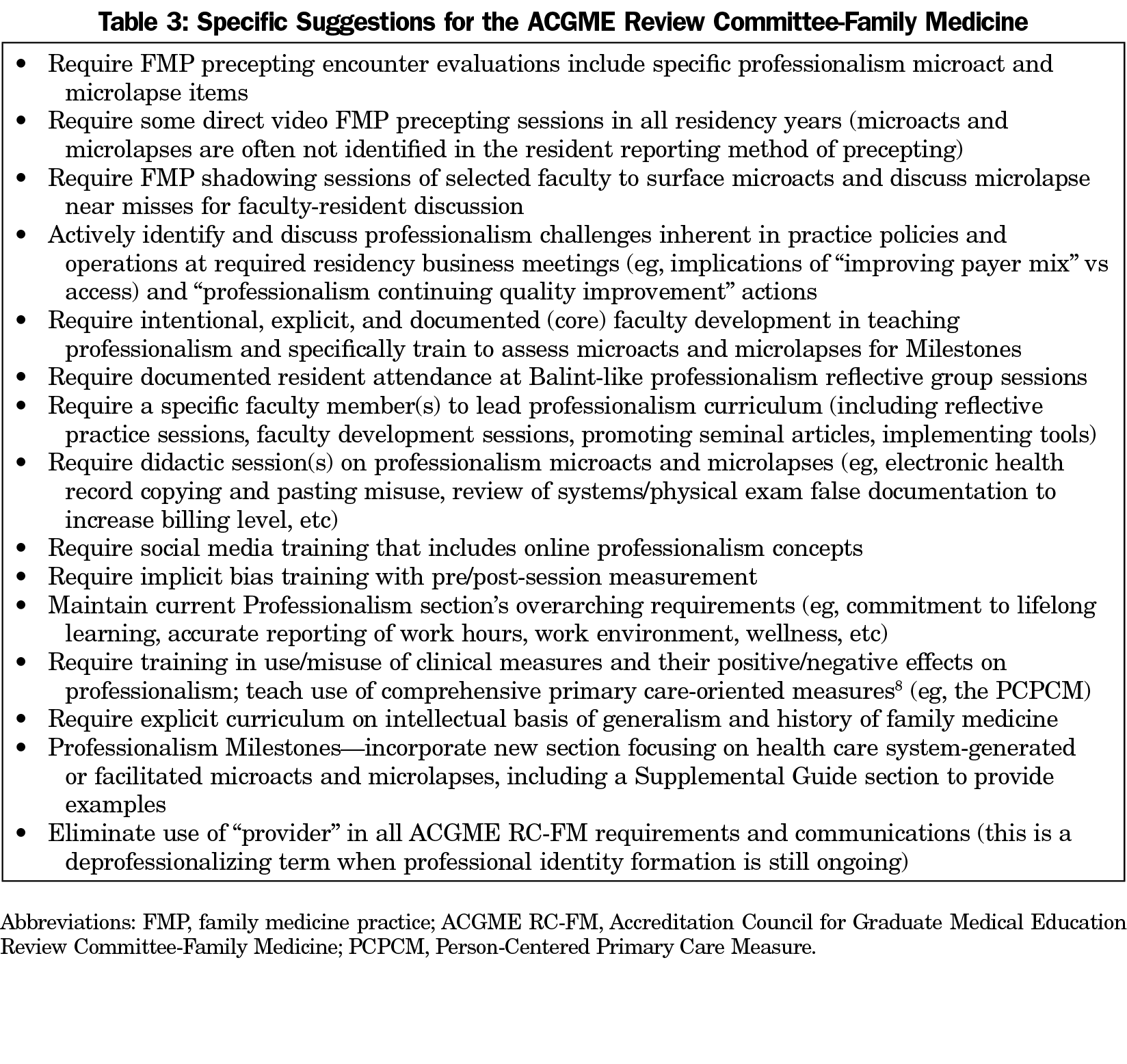

Because microlapses are so common, numerous opportunities for improving professionalism training exist if the events can be surfaced. Specific suggestions (Table 3) most notably focus on:

- Facilitated reflective practice educational sessions and more granular evaluation;

- Direct precepting and shadowing to better identify microlapses and positive microacts;

- A new Milestones section focusing on microlapses and microacts;

- Required curriculum on identifying daily inherent business/medical professionalism conflicts;

- Training in positive microacts that eliminate/minimize the practice environment’s structural barriers to professionalism, perhaps best thought of as “professionalism continuous quality improvement.”

Other remaining questions to inform a revision of program requirements include the role of learned helplessness in deprofessionalization and the potential positive role of a deeper understanding of generalism. Does family medicine still have a shared set of values in these areas? As the specialty grows older, most faculty and residents do not know the history of the specialty, what were the unique aspects of professionalism that family medicine founders brought to the table, and why they did so. This lack of knowledge may come up in subtle ways that impact professional beliefs and ultimately actions. A targeted educational requirement would be helpful in developing and positively affecting family medicine professional identity. Such an educational requirement could clarify our specialty’s self-identity and even facilitate needed health care reform to benefit the public.

References

- Guidelines for Professionalism, Licensure, and Personal Conduct, Version 2019-8. American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM). https://www.theabfm.org/sites/default/files/PDF/ABFMGuidelines.pdf. Accessed March 1, 2021.

- Ofri D. The Business of Health Care Depends on Exploiting Doctors and Nurses. New York Times Sunday Review. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/06/08/opinion/sunday/hospitals-doctors-nurses-burnout.html. Published June 8, 2019. Accessed March 1, 2021.

- Schwenk TL. What does it mean to be a physician? JAMA. 2020;323(11):1037-1038. doi:10.1001/jama.2020.0146

- Vicini A, Shaughnessy AF, Duggan AP. Cultivating the inner life of a physician through written reflection. Ann Fam Med. 2017;15(4):379-381. doi:10.1370/afm.2091

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR. Professionalism, communities of practice, and medicine’s social contract. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33(suppl):S50-S56. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2020.S1.190417

- Liaison Committee for Medical Education. Functions and Structure of a Medical School. Association of American Medical Colleges and American Medical Association. March 2020; Element 3.5. https://lcme.org/publications/. Accessed March 5, 2021.

- Cruess RL, Cruess SR, Boudreau JD, Snell L, Steinert Y. A schematic representation of the professional identity formation and socialization of medical students and residents: a guide for medical educators. Acad Med. 2015;90(6):718-725. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000700

- Etz RS, Zyzanski SJ, Gonzalez MM, Reves SR, O’Neal JP, Stange KC. A new comprehensive measures of high-value aspects of primary care. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(3):221-230. doi:10.1370/afm.2393