Racial inequality impacts the health of every community in the United States. The family medicine workforce of the future can address these racial inequalities by promoting diversity and inclusion in residency training.

COMMENTARIES

Diversity in the Family Medicine Workforce

Yalda Jabbarpour, MD | John Westfall, MD, MPH

Fam Med. 2021;53(7):640-643.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2021.284957

Diversity in the workforce can take many forms, including racial/ethnic diversity, language diversity, cultural diversity, gender diversity, diversity in economic or rural upbringing, and family educational background (Table 1). Although the concept of diversity can take many forms, attention to racial diversity is paramount to the health and well-being of our communities.

We know that a physician’s background and upbringing influences where and how they practice. Physicians raised in rural communities are more likely to work in rural communities. Underrepresented minorities (URM) are more likely to work in underserved communities of color. Medical students who are the first generation to go to college are more likely to choose a primary care career. All these factors have implications for our workforce and the health of the communities we serve. Residencies should train a workforce that can meet the unique needs of the patient population they serve. For some communities, this means addressing rural workforce shortages, for others it means addressing lack of access to obstetric care or mental health care, but for all communities in the United States it means addressing structural racism and racial inequality.

One way we can start to address structural racism and racial inequality is by looking inward at our discipline. Physicians are not immune to racial bias or stereotyping, and as the Institute of Medicine report Unequal Treatment demonstrated, these internal biases can lead to worse outcomes for patients of color.1 In addition, multiple studies have shown that patient/provider racial concordance leads to better patient-provider communication, better adherence to medical advice, and higher patient satisfaction.2,3 As a discipline, we have an opportunity to influence racial inequalities by fostering a family physician workforce where everyone is represented and valued.

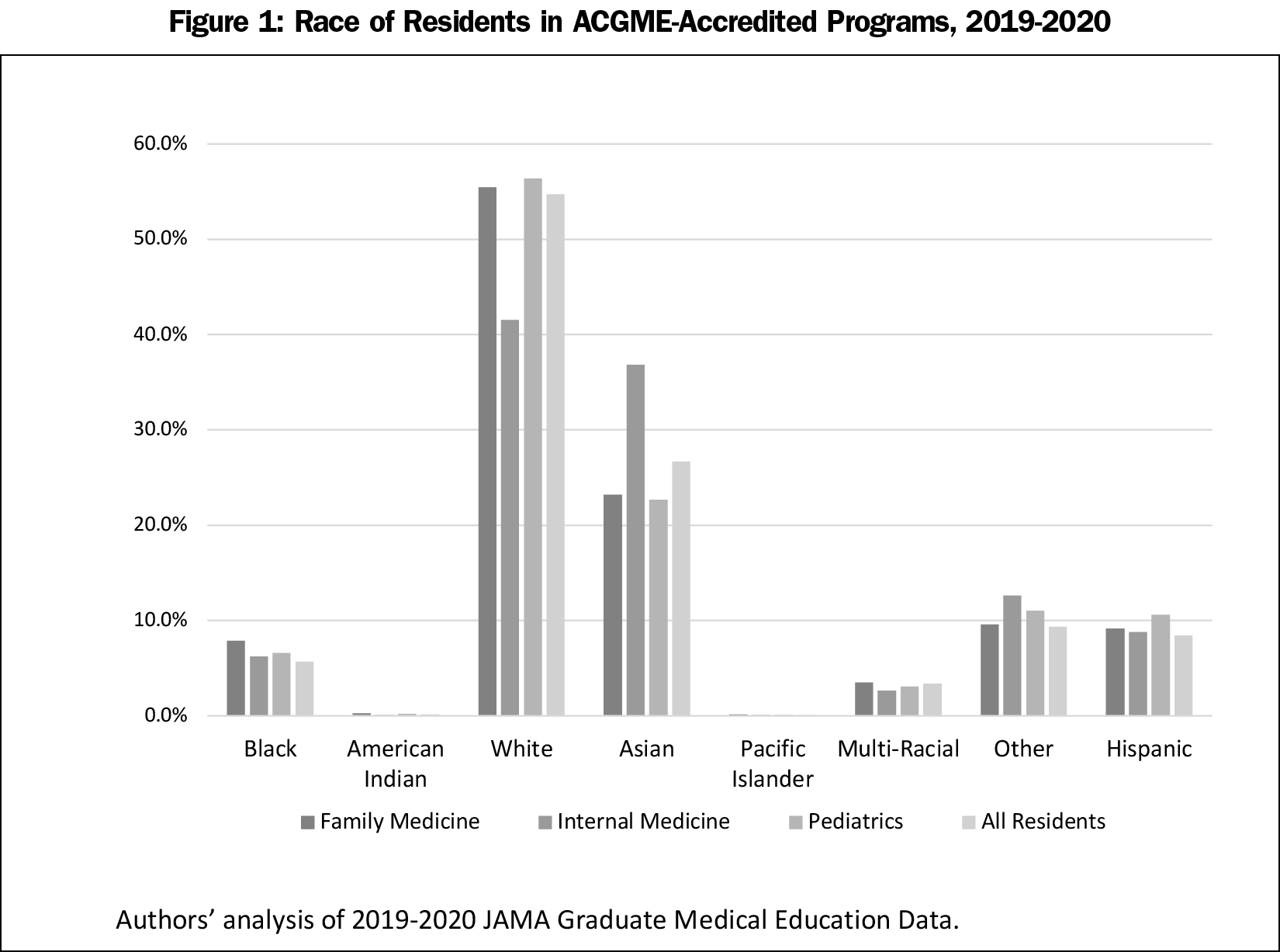

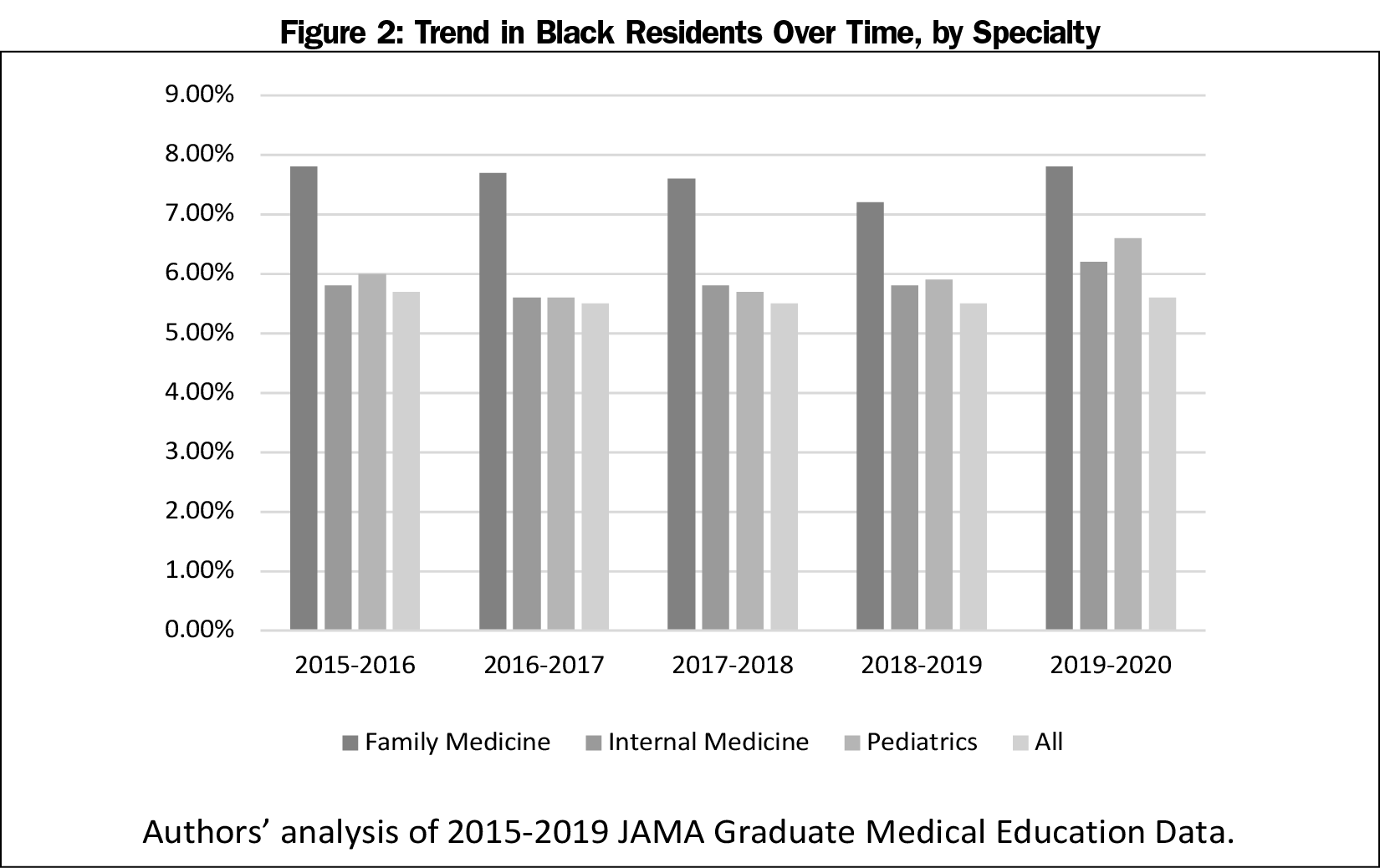

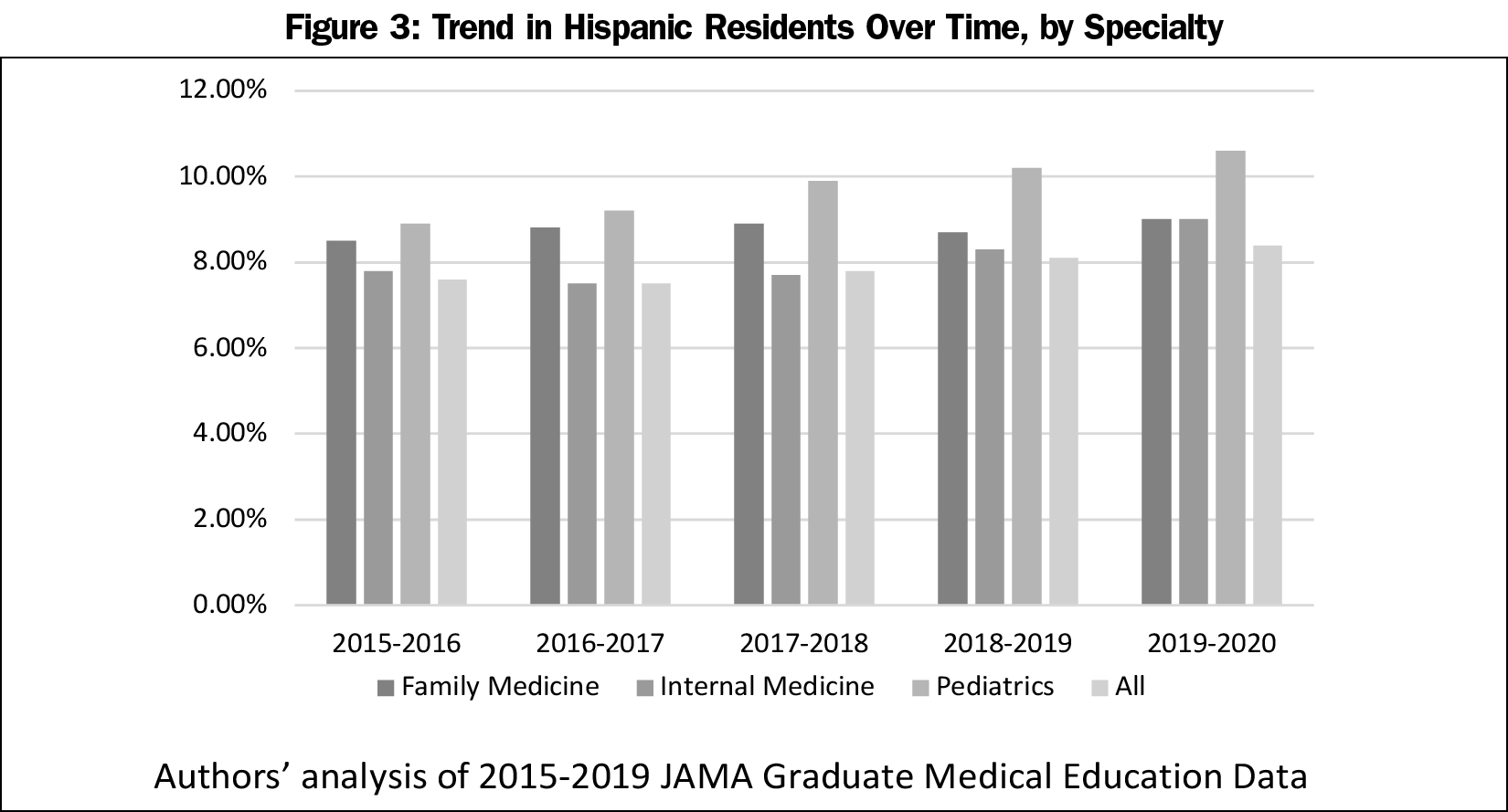

Although 13.4% of the United States population is Black and 18.5% of the population is Hispanic, only 7.8% of family medicine residents in 2019 were Black and 9.1% of family medicine residents were Hispanic.5 The family medicine workforce still lags behind other primary care specialties in their representation of Black and Hispanic physicians, yet family medicine residencies are achieving higher levels of Black and Hispanic representation than some of their primary care counterparts.4 Over the last 5 years, family medicine residencies have had a higher percentage of Black residents compared to internal medicine and pediatrics, and a higher percentage of Hispanic residents compared to internal medicine. Yet, there is work to be done given the plateau in rates of URM in family medicine residencies over this same time period (Figures 1-3). To this end there are steps we can take in residency recruitment and structure to promote the growth of a more racially diverse workforce.

The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has begun to tackle the need to increase diversity through accreditation by enacting several common program requirements.6 These include recruitment and retention of a diverse workforce and cultivating environments that are free from discrimination or harassment. Family medicine should set processes in place to not only achieve these goals but to exceed them. A recent study published in Family Medicine outlines steps one residency took to achieve the goal of increased diversity in their program, steps that can be adapted for residencies nationwide.7 The first step would be to increase the numbers of URM choosing family medicine. This could be done through increasing outreach to URM communities, hiring a director of diversity in the residency to ensure diversity recruitment, revising residency interviews to be less biased, and analyzing recruitment data so that residencies can track their progress over time. The second step would be fostering an environment where diversity is valued, and residents feel that they are represented. This would mean ensuring that there are URM on faculty, pairing each resident with a mentor who reflects their culture and values, and ensuring there are processes to discuss discrimination or bias without fear of retaliation. Because every residency is unique, the goal would not be to dictate the exact interventions, but to ensure that there is implementation of a strategic plan for recruitment and support of a racially diverse resident workforce.

Improving racial diversity in our residencies is only part of the answer to achieving health equity for our patients. Although it is important to grow the numbers of URM in residency, much of the work of diversifying the physician pipeline starts well before residency and may be out of the hands of the residencies themselves. Where many residencies may have more control is in preparing residents of all backgrounds to understand implicit bias, structural racism, and how these factors impact health. Implicit bias training has been shown to reduce implicit bias in individuals as demonstrated by lower implicit association test scores.8 But whether these effects are long lasting or actually change behavior has been questioned, and implicit bias training done incorrectly can actually perpetuate biases. Meaningful change will require our residencies to do more than just offer implicit bias didactics. We must create venues to openly discuss racism and its effects on our trainees and patients. We must include upstander training for our residents so that they have the tools to advocate for their colleagues and patients. Finally, we must train our learners on the importance of not only the social determinants of health, but also the political determinants of health. We can no longer pretend that health care only happens within the four walls of our exam rooms. In fact, it is more obvious now than ever, that improving the health of our minority communities is completely dependent on fixing the policies that have negatively impacted their health for decades. It is incumbent upon our residencies to train a workforce that understands how to effectively advocate for change at a local, state, and national level. Community Advocacy is included in our current ACGME Milestones and must be emphasized by programs as much as patient care and medical knowledge. Physicians have always been leaders in their communities, and for the family physician of the future this means influencing policy, and not allowing policy to influence them.

Although racial inequality is arguably the most important factor plaguing the health of our communities, diversity of the family physician workforce and how it impacts community needs is not as straightforward as simply focusing on race. Table 1 outlines some of the ways in which the family medicine workforce is unique in terms of who they are and where they practice. To examine each one of these factors individually is beyond the scope of this commentary. But the philosophic constructs described here could be applied to any one of these factors. A residency must have processes in place to recruit a diverse workforce (however they define that), foster an environment of inclusion, and provide a curriculum that teaches their residents to address the diverse needs of their community and advocate for policies that impact the health of their patients.

There are over 10,000 physicians being trained in family medicine—over 4,000 new graduates per year. With the right attention to diversity and health equity, family medicine has the opportunity to truly improve the health of each of our patients, and the life of all of our communities.

References

- Institute of Medicine. Unequal Treatment: Confronting Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Health Care. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2003. doi:10.17226/12875

- Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):907-915. doi:10.7326/0003-4819-139-11-200312020-00009

- Shen MJ, Peterson EB, Costas-Muñiz R, et al. The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: a systematic review of the literature. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(1):117-140. doi:10.1007/s40615-017-0350-4

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA. The racial and ethnic composition and distribution of primary care physicians. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29(1):556-570. doi:10.1353/hpu.2018.0036

- United States Census Bureau. US Census Bureau Statistics: Quick Fackts. https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/US/PST045219. Accessed March 14, 2021.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Diversity, Equity and Inclusion. https://www.acgme.org/What-We-Do/Diversity-Equity-and-Inclusion. Accessed March 14, 2021.

- Wusu MH, Tepperberg S, Weinberg JM, Saper RB. Matching our mission: a strategic plan to create a diverse family medicine residency. Fam Med. 2019;51(1):31-36. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.955445

- Stone J, Moskowitz GB, Zestcott CA, Wolsiefer KJ. Testing active learning workshops for reducing implicit stereotyping of Hispanics by majority and minority group medical students. Stigma Health. 2020;5(1):94-103. doi:10.1037/sah0000179

Lead Author

Yalda Jabbarpour, MD

Affiliations: Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Family Medicine and Primary Care, Washington, DC

Co-Authors

John Westfall, MD, MPH - Robert Graham Center for Policy Studies in Primary Care and Family Medicine, Washington, DC

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.