“Excellence is an art won by training and

habituation.” —Aristotle

COMMENTARIES

Recruiting, Developing, and Supporting Family Medicine Faculty for the Future:

Three “T’s” to Enable Achieving the Additional “C” Required of Family Medicine Educators

Stephen A. Wilson, MD, MPH | Tomoko Sairenji, MD, MS

Fam Med. 2021;53(7):644-646.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2021.540628

Family medicine (FM) delivers first-contact, complex, comprehensive, coordinated care over a continuous period of time in the context of community. Learners do not leave medical school prepared to do this; the transformation occurs during residency. This is neither accident nor magic, but due to deliberate competency-based education (CBE). Hence, an additional “C”—competency for faculty in delivering CBE—becomes of paramount importance as for family medicine educators.

The advent of CBE followed by duty-hours regulations hastened the evolution of FM education to meet the changing needs of its context and community. The demands of CBE moved us past the anachronistic days of, “See one, do one, teach one.” Educators had to become more than resident trainee safety guardrails with keen clinical acumen and exemplary bedside skills. “No news is good news” was no longer acceptable feedback. To meet the requirements of CBE, FM educators needed to add and develop educational skills in areas such as curriculum development, direct observation, feedback (formative and summative), scholarship, quality improvement, population health, and team-based education, many of which had not been part of their own education.

Problem

There are three main challenges posed by CBE and the evolving context of FM education: (1) faculty skills required to effectively fulfill CBE; (2) increasing number of FM residents, especially with the expressed goal of 25% of US medical school graduates choosing FM by 2030; and (3) the relative youth and inexperience of those becoming FM faculty, which will only increase as the number of residents increases.

Strategy

CBE is intentional and requires resources: time, treasure, and training. Time, for faculty to develop skills and to execute the requirements of milestone-guided CBE. Treasure, for there is a financial cost to educating, observing, and evaluating. Training, because becoming a competent educator requires skills additional to being a competent clinician.

Time. Effective delivery of CBE requires more time and trained people (faculty and administrative support) than the historical training model. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) describes the role of core faculty and set a ratio of one core family physician faculty, additional to the program director, for every six residents.1 It does not, however, indicate the amount of time they should dedicate to the educator portion of clinician-educator. The Society of Teachers of Family Medicine (STFM) is finalizing “Joint Guidelines for Protected Non-Clinical Time for Faculty” to standardize this.

Core faculty should have 20%-30% time dedicated to nonclinical tasks vital for effective medical student and resident education, eg, direct observation, feedback, video review, assessment (learner and program), curriculum development, advising/mentoring/coaching, and remediation.

Faculty 3 or less years removed from residency should be 80%-90% clinical, directly seeing their own patients or precepting (directly and indirectly seeing patients with learners). Many of the founders of FM were “clinical giants.” Too often program needs results in prematurely introducing junior faculty into managerial or leadership roles before their formations as physician and educator are complete. This rush is a disservice to them and their learners, and can result in faculty attrition due to anxiety, burnout, or a sense of imposterism.

How do we enable the thing most vital to FM education: recruiting, developing, and retaining our best and brightest as faculty? In addition to describing the work of faculty and providing them time to do it, we do this by investing additional treasure and supporting their training.

Treasure. Leaders in FM education frequently recount stories of losing their most promising faculty prospects to private practice due to salary and/or debt issues. According to the American Association of Medical Colleges, the 50th percentile indebtedness of 2020 graduates was $184,009 (10th percentile, $123,692; 90th percentile, $230,878). Other disciplines have salary gaps between clinical and academic practitioners; however, for FM there is an additional gap of FM vs specialist compensation. For some the gap is thrice widened given the propensity for academic practices to be in areas with higher proportions of uninsured or Medicaid patients. This occurs concomitantly with call that often carries an enhanced intensity related to managing residents of variable and developing abilities, volume, and patient demographics. As such, faculty salaries should be reasonably commensurate with their local market. Loan forgiveness should be available where faculty patient practice demographics are consistent with those in federally qualified health centers. This could come from federal, state, local, and health systems, all entities who benefit from faculty and resident work in this population.

In addition to aiding the salary aspects of recruitment and retention, financial support is also necessary to equip faculty with adequate training.

Training. Faculty skills training should be required, both initially and ongoing. A “see one, do one, teach one” approach is as inadequate for the educator training side of clinician-educator as it is for the clinical side.

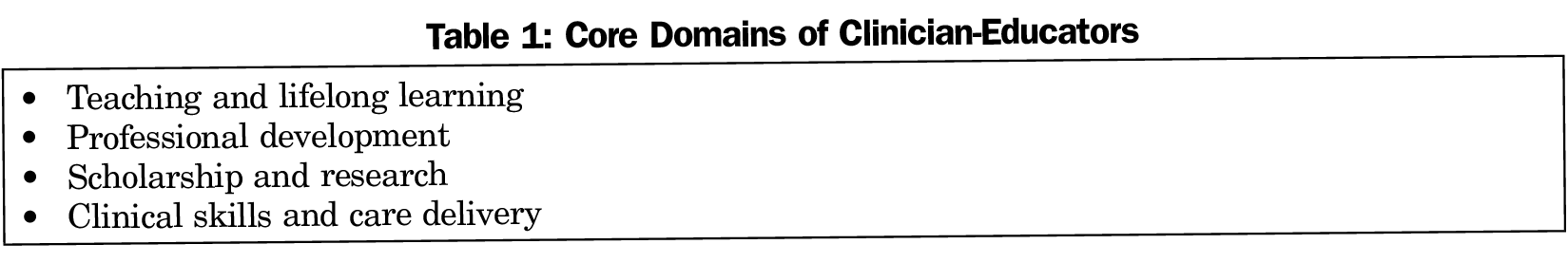

Being FM faculty goes far beyond precepting and clinical consulting. Much has been written about the core domains, competencies, and skills required to become a competent FM faculty.2-7 Within each of the typically included core domains for clinician-educators (Table 1) are a number of competencies. While it is outside the scope of this commentary to lay out a comprehensive list, here are two examples. Competencies in the domain of teaching include developing a climate conducive to learning; actively engaging learners; assessing learner’s knowledge, skills, and attitudes; facilitating learners’ educational goals; providing effective feedback; and reflecting on and assessing one’s own teaching competence. Each of those in turn has demonstrable actions or principles.8 Competencies under professional development include leadership; administration and management; and communication, both written and oral.

Many excellent faculty prospects are either dissuaded from or desert an educator path due to personal concerns about lack of faculty skills, both academic and clinical. Despite that, FM faculty are getting younger.9 STFM membership increased 8% from 2017 to 2020 with members under 40 years of age rising from 28% to 39%.9 This suggests FM educator is a first-line career pathway, no longer reserved for those who pursue private practice prior to becoming faculty. The youth movement is a by-product of interest and need for more faculty given the increased number of residency programs and the increased requirements to effectively execute CBE. However, faculty attrition is high; only 43% of first-time assistant professors at medical schools are in the same place 10 years later.6

Requiring and completing adequate training might encourage high-quality graduates to choose and remain in academic careers. Part-time, early-career, structured faculty development (FD) bolsters academic skills, strengthens professional identity, and increases confidence.6 Completion of a full-time, 2-year FD fellowship decreased faculty attrition from academia and increased faculty scholarship (peer-reviewed publications and presentations) by 67% compared to nonfellowship-trained faculty.6

Training in faculty skills should be required by the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME), both initially and ongoing. Given that fellowship programs, especially full-time, are few and underfunded, how could this necessity be fulfilled? The answer is that it would occur like it did for trainees; the ACGME should develop a faculty competency list and framework. These core faculty requirements could be acquired and demonstrated, for examples in FD fellowship, through a master’s degree in education, or they could be part of a 4-year residency program. If those options are unavailable or infeasible, an online certificate or fellowship program could be completed during the first 2 years of being faculty. Inexpensive programs like this already exist, one example being the STFM Faculty Fundamental Programs.10,11 This initial training should be fortified annually via dedicated educator continuing medical education that counts toward the American Board of Family Medicine’s Continuous Certification process. This would encourage competency-based faculty development to routinely refine skills and incorporate new evidence from education and medical education literature.

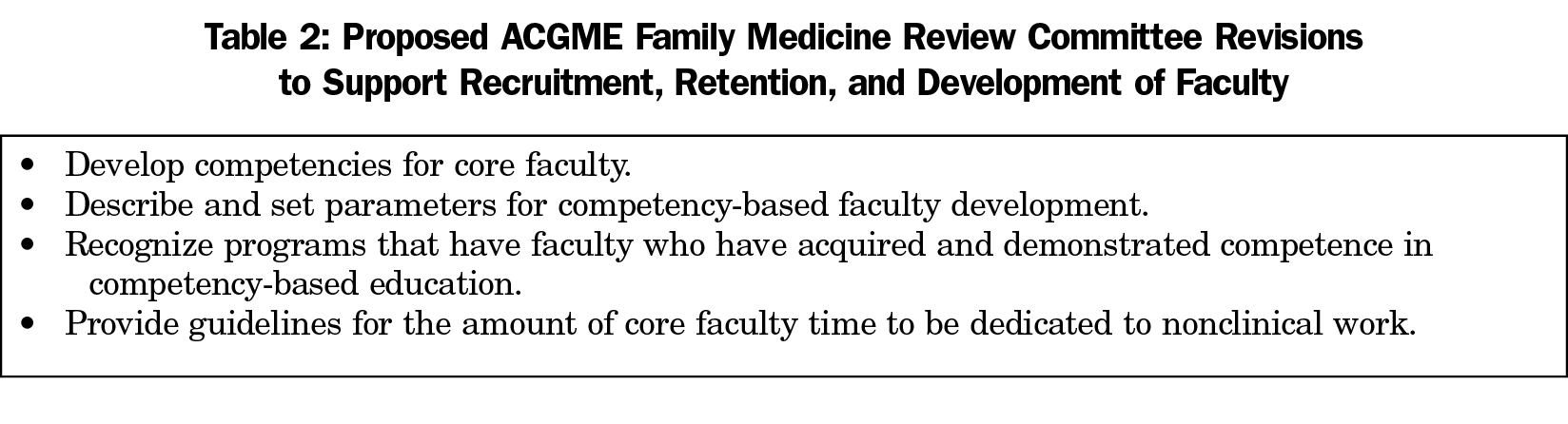

Addressing these 3T’s will help address the needs for greater numbers of more skilled faculty as the number of FM residents increases. It will also increase the ability to recruit (salary, debt load, preparation), develop (skills and professional identity), and retain (on-going training and work environment) faculty. The ACGME Family Medicine Review Committee has an opportunity to advance the recruitment, development, and support of future FM faculty (Table 2).

CBE was introduced to set expectations and increase patient safety by decreasing variance in training and increasing transparency and accountability. The roles and tasks of FM educators are substantial and growing. It will take time, treasure, and training to recruit, develop, and support FM faculty who are equally clinician and educator, and fully-equipped to deliver effective, competency-based resident education.

References

- ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. Chicago: Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; 2020. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/120_FamilyMedicine_2020.pdf. Accessed November 2, 2020.

- Bland CJ, Schmitz CC, Stritter FT, Henry RC, Aluise JJ. Successful Faculty in Academic Medicine: Essential Skills and How to Acquire Them. Vol 12. New York: Springer Publishing Company, Inc; 1990.

- Harris DL, Krause KC, Parish DC, Smith MU. Academic competencies for medical faculty. Fam Med. 2007;39(5):343-350.

- McGaghie W. Handbook for the academic physician. New York: Springer Verlag; 1986. doi:10.1007/978-1-4684-6328-6

- Taylor R. Academic medicine: A guide for clinicians. New York: Springer; 2006.

- Sairenji T, Jarrett JB, Baldwin L-M, Wilson SA. Overview and assessment of a full-time family medicine faculty development fellowship. Fam Med. 2018;50(4):275-282. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.190747

- Jarrett JB, Sairenji T, Klatt PM, Wilson SA. An innovative, residency-based, interprofessional faculty development program. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2017;74(6):402-408. doi:10.2146/ajhp160106

- Bing-You RG, Lee R, Trowbridge RL, Varaklis K, Hafler JP. Commentary: principle-based teaching competencies. J Grad Med Educ. 2009;1(1):100-103. doi:10.4300/01.01.0016

- STFM Membership Data: 2017-2020. Email correspondence, November 20, 2020.

- STFM Residency Faculty Fundamental Certificate Program. Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. https://stfm.org/facultydevelopment/certificateprograms/residencyfacultyfundamentals/overview/ Accessed November 12, 2020.

- STFM Medical School Faculty Fundamental Certificate Program. Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. https://stfm.org/facultydevelopment/certificateprograms/medicalstudentfacultyfundamentals/overview/. Accessed November 12, 2020.

Lead Author

Stephen A. Wilson, MD, MPH

Affiliations: Boston University/Boston Medical Center, Boston, MA

Co-Authors

Tomoko Sairenji, MD, MS - University of Washington, Department of Family Medicine

Corresponding Author

Stephen A. Wilson, MD, MPH

Correspondence: 1 Boston Medical Center Place, Dowling 5 South, Room 5309, Boston, MA 02118.

Email: stephen.wilson@bmc.org

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.