In winter 2020, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) announced plans for a major revision of the family medicine residency requirements. Over the last year, the specialty has developed its vision for the future of residency education in focus groups and surveys, a national Starfield summit, and this dedicated issue of Family Medicine. The purpose of this paper is to describe this specialty-wide effort and introduce the core questions and the papers in this issue.

This major revision will shape the form and promise of family medicine for the next generation. ACGME major revisions occur approximately every 10 years. Assuming a 30- to 40-year practice life, residents trained under the new standards will be in practice until the 2060s. Furthermore, what happens in residency matters. There is increasing evidence that residencies set fundamental patterns of practice in graduates, ranging from operative rate and medication selection to quality and cost of care.1-3 These patterns endure for many years, and are thus foundational to any effort to improve health, improve patient experience, and reduce cost.

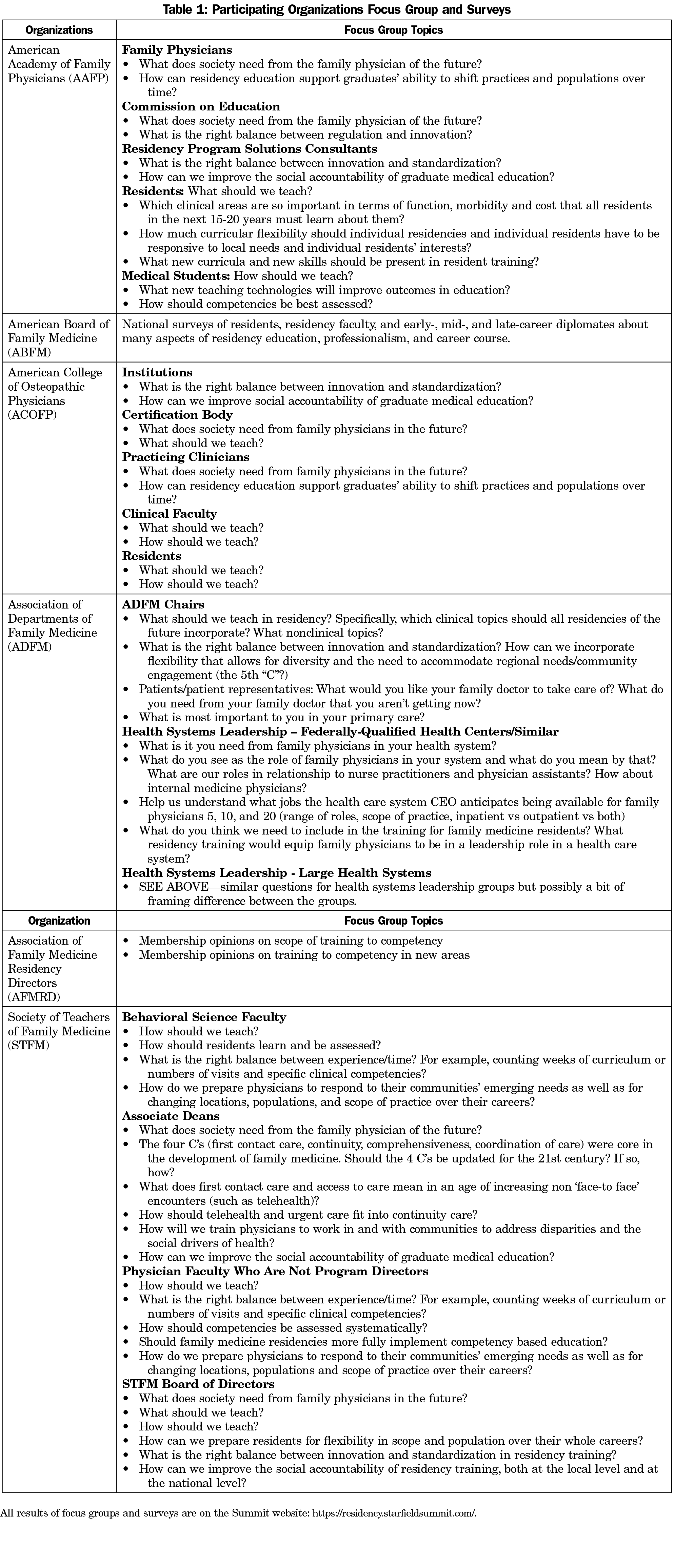

Coordinating their work with that of the ACGME, the seven clinical and academic organizations of family medicine organized a national initiative to reenvision the future of family medicine residency education. The American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP), American Board of Family Medicine (ABFM), American College of Osteopathic Family Physicians, the Association of Departments of Family Medicine, Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors, NAPCRG, and the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine each identified one representative to a task force to coordinate the effort. ABFM and AAFP staff led the effort. With input from their organizations, the task force identified and published six core questions4 for the specialty to address; these were used by the organizations to frame focus groups and surveys to get input. Researchers from the specialty prepared 15 background papers on various aspects of family medicine residency education to support discussions. Table 1 lists focus group topics and surveys conducted in the summer and fall of 2020 by organization. Overall, over 3,500 people participated in the process in some way.

A national summit was held on December 6-7 to build consensus for recommendations to the ACGME writing group. NAPCRG conferred the name Starfield Summit, underscoring the foundational importance of Barbara Starfield’s research to residency education in family medicine. After a national call for nominations across all family medicine organizations, over 170 nominations were received, and 52 people were selected, with planned diversity by underrepresented minority, gender, career phase, national geography, rurality, osteopathy, and profession to include behavioral health and pharmacy. Residents, medical students and five patient and public members were also included. Observers included the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Residency Standards writing group, the ABFM Residency Task Force, and leadership of the American Board of Medical Specialties and the ACGME. In advance of the summit, nine evidence summaries and 24 commentaries were commissioned, and drafts were made available to all participants and observers 10 days in advance of the meeting. The summit was organized to be as interactive as possible, with engagement through expected prereading and a variety of techniques, including having the majority of time for discussion, flipped classroom, pre- and postpolling, and small groups; separately, affinity groups by career phase and region of the country met. The participants and agenda are available on the website. Each of the six sessions was brought to closure with straw polls, or, in the case of master adaptive learning, focus groups. The final straw poll results are also posted on the website.5 Of course, participants were not directly representative of the approximately 115,000 family physicians and family medicine residents in the country, but they do represent the best judgement of a representative group of stakeholders after preparation, presentations, and discussion. The summit website5 includes the core questions, the focus group and survey results, key documents, the summit agenda and participant list, and will include the papers as they are published. This issue of Family Medicine includes the commissioned papers after presentation, peer review, and revision.

In the short term, the goal was to develop recommendations for the ACGME Family Medicine Review Committee as it drafts the new requirements and for the ABFM as it defines future board eligibility. More broadly, however, the stakeholders are the specialty of family medicine and the public. The social contract that binds the profession of medicine to society demands that family physicians self-regulate, and residency education is a fundamental component of that commitment. The AAFP produced the summit; the ABFM developed the permanent website, and the ABFM Foundation is financing this special issue of Family Medicine.

What follows frames the context of the key questions and introduces the papers. American health care has always been dynamic, but the amplitude and speed of recent changes have not been seen in two generations; they represent transformation. Major components include consolidation of hospitals and health systems, rapid spread of integrated electronic health records and employment of physicians. The majority of US physicians are now employed, as are almost 70% of family physicians.6 A second phase of transformation is just beginning. Augmented intelligence promises to change health care as much as has already happened in banking and retail businesses. Changes in genomics are revolutionizing cancer and autoimmune disease treatment and promise more. Attracted by margin, new business models such as CVS/Aetna are coming into medicine; the COVID pandemic will bring not just telehealth, but also lasting changes in the organization and financing of health care.7

Unfortunately, despite transformation of care, and despite health care reform, the population outcomes of health care in the United States are the worst among developed countries and the gap is growing. As the National Research Council demonstrated,8 Americans are sicker and die earlier than citizens of comparable countries. This is true at all ages and for almost all diseases—and at a health care cost much greater than comparable countries. As examples, Figure 1 depicts the likelihood of survival of women beyond 50,8 and Figure 2 compares US public and private health care expenditure to similar countries.9 More recently, it has become clear that US life expectancy has begun to decline, as the result of increased mortality from many diseases.10 This was apparent even before the COVID pandemic highlighted dramatic disparities of incidence and mortality for Blacks, Hispanics, Native Americans, and the poor. At the same time, however, despite the demands of the Affordable Care Act and huge market demand, numbers of students from allopathic medical schools interested in family medicine have begun to drop, burnout is widespread and scope of practice is diminishing.11

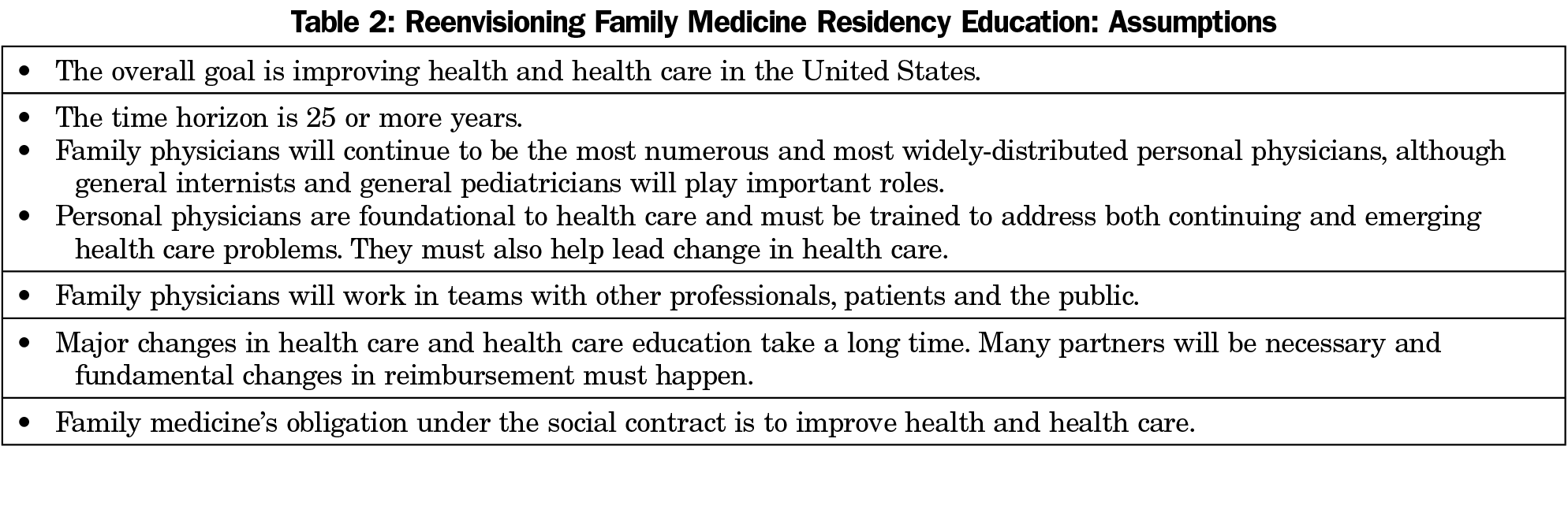

Key assumptions for the work are listed in Table 2. The premise of the summit was that the needs of society are changing, and family medicine residencies must change to meet society’s needs—and that family physicians must help lead change. Other assumptions included a more than 25-year time frame, and that family physicians will continue to be the largest and most widely distributed tribe of personal physicians, while working in teams with other professionals and patients. Major changes in health and health care will take a long time, many partners will be necessary and fundamental changes in reimbursement must happen. The road is long, but under the obligations of the social contract, the specialty must begin the work.

The Core Questions and Their Rationale

What Does Society Need From the Family Physicians of the Future?

Since the founding of family medicine, patients and health care itself have changed dramatically. Many new major clinical problems have emerged, including greatly increased multimorbidity, epidemic opiate abuse, and the COVID pandemic. In addition, serious disturbances of the health care system have emerged, from increases in maternal mortality, emerging maternity care deserts,12 continuing cost and quality concerns about hospital care, high-cost and often poor-quality transitions of care, and strikingly unequal care across race, ethnicity, social class, and region. Norman Kahn, MD, describes these changes and argues that a first step toward change is the transformation of family medicine residency practices: we must be the change we wish to see in health care and in society.13

Foundational to the discussion is the extensive research exploring the source of the primary care benefit: why and how primary care improves population health, quality, and cost-effectiveness. Andrew Bazemore, MD, MPH, describes the abundant evidence that first-contact care, continuity, comprehensiveness, and coordination of care are all essential to improve population health, describes how they should be updated, and argues that they should be the foundation of family medicine residency education.14 Moreover, in the context of the civil rights movement triggered by the murder of George Floyd, should we also refocus on community as an additional pillar of family medicine residency education?

The scope of practice for which family medicine residents should be trained is also a key issue. Should all family physicians be trained to do hospital care, take care of pregnant women, and engage in community interventions? Citing a recent reduction in scope of practice of family physicians, some in our community have argued against full-scope training. Yet in many communities, family physicians’ broad scope is essential for day-to-day care. Moreover, the large problems society faces in hospital care and maternity care are getting worse with family physicians moving to the sidelines, even as the pandemic has demonstrated the value of plasticity of the family medicine workforce. Commentaries address the importance of hospital care, maternity care, integrated behavioral health, and engaging communities.15-18

What Should We Teach?

The clinical and health care problems for which we train influence curricular time and content. The dimensions are important—hospital care, care of pregnant women, integrated behavioral health, and community engagement—but so too are subjects that need more attention such as multimorbidity, rural health, osteopathic principles, and professionalism, along with enabling competencies such as team-based care and addressing diversity and disparities. Many would demand the development of novel educational structures and curricula. A series of commentaries make specific recommendations for future residency content.19-25 Adding topics, of course, forces consideration of what to take out of the residency. The website includes results from the AFMRD survey of residency directors26 and the ABFM surveys of residents27 and residency faculty,28 and about this issue. It should be noted, however, that the summit was not organized to focus on the specifics of new curricula and innovations in teaching; ultimately this is the responsibility of the specialty and its faculty.

Beyond scope of practice and elements of curriculum, a broader theme of the summit was that residents’ continuity practice is a fundamental part of their education: the practice is the curriculum. Residents learn by doing, and what they learn by doing they keep doing for years. The ABFM survey underscores that only a minority of family medicine residents are currently empaneled or get feedback about access or cost-effectiveness. Neutze and her colleagues emphasize the importance of the experience in the residency practice and argue that all patients in residency practices be empaneled, and that the practices meet standards of access, continuity, quality and cost of care, framed within a mission of improving population health and implementing the quadruple aim.29 Robert Phillips, MD, MSPH, underscores the importance of imprinting of basic habits in residency,1 while Charles Lehmann, MBA, and Winston Liao, MPH, describe the key importance of patients and a patient advisory committee in the residency practice setting.30 Finally, Grant Hoekzema, MD, reviews what is known from data routinely collected by the ACGME about residency practices.31

How Should We Teach?

Over the last 15 years, there has been increasing interest in robust competency-based education across stages of medical education and across professions. In graduate medical education, the pioneer was orthopedics.32 Implementation of competency-based graduate medical education (CBGME) in a generalist specialty, however, is a particular challenge. Eric Holmboe, MD, describes the history of CBGME, and lessons for implementation from other specialties and from undergraduate medical education.33 John Saultz, MD,34 describes the challenges of faculty time and development that CBGME faces, and Suzanne Allen, MD, MPH,35 describes lessons learned from the implementation of milestones in family medicine. From the perspective of a similar Canadian commitment to full scope family medicine, Nancy Fowler, MD,36 describes lessons learned after years of emphasis on competency-based education. She distinguishes between competence and confidence, and underscores the implications of social accountability of family medicine residency education.

Critically important to the residency standards is the duration of family medicine residencies and the initial phase of clinical education. Over the last 7 years, there has been a formal trial of 3 vs 4 years duration of family medicine residencies; long-term outcomes are now beginning to be published, with initial papers on admissions and finances.37-39 Alan Douglass, MD, and Donald Woolever, MD, present a point/counterpoint on this issue.40 Warren Newton, MD, MPH, broadens the discussion by describing best practices from other specialties, including more substantial individual learning plans in pediatrics, oral examinations to assess judgment and complex decision making in many specialties and a phase of education and support for 1-2 years after residency.41

Pedagogy for didactic sessions is also important, given the dramatic advances in the science of learning since our founding in 1969. Simulation and observed structural clinical exams (OSCEs) have become important methods of teaching and assessment of medical trainees. An abundance of evidence shows that interactive teaching has much better outcomes than traditional lectures.42-44 Todd Zakrajsek, PhD, summarizes this data, and the website provides ABFM resident27 and faculty28 survey data about the prevalence of active learning nationally in residency didactic conferences.45

How Should We Train for Clinical Adaptability Over Careers and Across Communities?

As the pandemic has taught us, clinical adaptability, both of scope of practice and over careers, is fundamental to what society needs from personal physicians. How should family medicine residencies train for adaptability? What combination of broad initial training, specific skills, and commitment to meeting the changing needs of patients and communities will prepare residents for their future careers? The ABFM survey documents the high frequency of changes in practice, populations, and scope of practice over careers,27 and the website documents curricular ideas generated by small groups at the summit. Lou Edje, MD, MHPE, describes the emerging literature on master adaptive learning and gives initial recommendations about how to train for it.25

Building a Better System of Family Medicine Residency Education

What Is the Right Balance Between Innovation and Standardization?

The needs of society demand ongoing innovation in residencies as clinical needs and health care change. What, how, and where residents learn need to evolve. At the same time, standardization of training is also critical; we need to be able to promise to the employer and the community what a family physician will be able to do. Roger Garvin, MD, frames the tension between innovation and standardization in residency requirements and underscores the need for both, with emphasis on competency-based assessments to guide progress and assess outcomes of innovations and the need to develop networks of residencies to evaluate and spread innovation.46 ACGME milestones use a developmental perspective and provide national data on standardization. These data show that significant numbers of family medicine residents are not meeting many of the milestones. Deborah Clements, MD, reviews these data and emphasizes key issues to keep in mind as the specialty seeks to improve its system of residency education.47 Finally, it will be important to measure longer-term outcomes of residency outcomes. One important tool is the ABFM/AFMRD residency graduate survey. Lars Peterson, MD, describes its methods and potential value in improving the national system of residency education.48 The broader issue is using outcomes after residency to guide improvement of residencies while monitoring the changing needs of society.

How Effective Is Continuous Quality Improvement of Residency Programs?

The United States relies on a voluntary but universal system of residency accreditation through the ACGME. Current accreditation standards require residencies to use principles of continuous quality improvement to improve their residencies, and the ACGME uses administrative data and annual resident and faculty surveys to monitor residencies annually. Site visits are every 10 years or as necessary based on the recommendations of the Review Committee. How effective are these processes? ABFM survey data reveal a glass half full: most residency faculty believe that improvement does occur, but that important issues at both the residency and the institutional levels are missed.28 Peter Carek, MD MS, former chair of the Family Medicine Review Committee, describes the current ACGME procedures and expectations for ongoing improvement, and proposes new guidelines for improving self-improvement, suggesting that residencies address clinical and community outcomes in addition to educational outcomes.49 Public commitment to reporting would help the system be more robust.

How Can Social Accountability of the GME System Be Improved?

In most countries, there are explicit standards for social accountability of medical education.50 In the United States, however, the term is only rarely used and is not a part of formal policy. Yet our society’s needs have changed since the inception of Medicare funding of GME.51,52 Our expenditures on GME are substantial, in both public and private sectors, and the system has little formal oversight beyond financial accountability. How should we improve the social accountability of our national GME system? Arthur Kaufman, MD, and colleagues describe the current GME system through the lens of social accountability and propose steps to improve social accountability at the regional, state, and national levels.53

The Future of the Specialty

The summit focused on how changes in family medicine residency can meet the emerging needs of society. Another important issue, however, is the future of the specialty—what should residencies do to help the specialty develop and thrive over the next generation? Yeri Park, MD, gives a resident’s perspective on what is needed to make residencies attractive, and Stephen Wilson, MD, MPH, summarizes the challenges of recruiting, developing, and maintaining residency faculty and teachers.54,55 Yalda Jabbarpour, MD, underscores the importance of diversity of the family medicine workforce and describes how it may change, both in terms of demographics and in comparison to other specialties and professions focusing on primary care.56 The upcoming major revision also provides an opportunity to address a major strategic weakness of our specialty: the lack of a widespread and sustained tradition of research on issues of practice and policy critical for family medicine and primary care. Diane Harper, MD, MS, gives initial recommendations about how residencies can encourage and support future researchers.57 Finally, it will be important to train the leaders of the future to achieve improved health and health care. Myra Muramoto, MD, MPH, gives recommendations about how family medicine residencies can support development of future leaders across all the missions.58

Since its founding in 1969, family medicine has met society’s need for access to community-based physicians. The specialty has grown to become the largest and most widely-distributed group of personal physicians, delivering care for patients and communities across the country. Now, however, the amplitude and pace of transformation of health care in the United States is greater than at any other time in the last two generations. Despite enormous investment, technology-driven innovation, and the beginning of health care reform, the performance of our health system is falling further behind peer countries. Health indicators are not adequately improving, life expectancy is decreasing, and health inequities continue to plague us.

Personal physicians can and must contribute to improving health and health care, one patient at a time, one community at a time, one health system at a time, and one state at a time. Family medicine can help meet this challenge, as the specialty did 50 years ago, by changing our educational systems in service to society’s needs.

References

- Phillips RL Jr, Holmboe ES, Bazemore AW, George BC. Purposeful imprinting in graduate medical education: opportunities for partnership. Fam Med. 2021;53 (In press).

- Asch DA, Nicholson S, Srinivas S, Herrin J, Epstein AJ. Evaluating obstetrical residency programs using patient outcomes. JAMA. 2009;302(12):1277-1283. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1356

- Chen C, Petterson S, Phillips R, Bazemore A, Mullan F. Spending patterns in region of residency training and subsequent expenditures for care provided by practicing physicians for Medicare beneficiaries. JAMA. 2014;312(22):2385-2393. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.15973

- Newton WP, Bazemore A, Magill M, Mitchell K, Peterson L, Phillips RL. The future of family medicine residency training is our future: a call for dialogue across our community. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33(4):636-640. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2020.04.200275

- Starfield Summit Re-Envisioning Family Medicine Residency Education. 2020 https://residency.starfieldsummit.com/. Accessed September 12, 2020.

- JAMA Career Center - Practice Arrangements. Employment Trends Report. https://careers.jamanetwork.com/article/employment-trends-report-practice-arrangements. Published July 10, 2019. Accessed April 9, 2020.

- Newton W, Peterson L, Morgan Z, et al. Rebuilding after COVID: planning systems of care for the future. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33(3):485-488. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2020.03.200135

- National Research Council; Institute of Medicine. U.S. Health in International Perspective: Shorter Lives, Poorer Health. Woolf SH, Aron L, editors. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2013. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK115854. Accessed May 27, 2021.

- Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development. Health at a Glance 2019: OECD Indicators. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/sites/876d99c3-en/index.html?itemId=/content/component/876d99c3-en. Accessed September 17, 2020.

- Woolf SH, Schoomaker H. Life expectancy and mortality rates in the United States, 1959-2017. JAMA. 2019;322(20):1996-2016. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.16932

- Coutinho AJ, Phillips RL Jr, Peterson LE. Intended vs reported scope of practice—reply. JAMA. 2016;315(20):2234-2235. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.1727

- Cullen J. New AAFP initiative addresses rural health care crisis. Ann Fam Med. 2019;17(471-472):471-472. doi:10.1370/afm.2450

- Kahn N. Redesigning family medicine training to meet the emerging healthcare needs of patients and communities - be the change we wish to see. Fam Med. 2021;53 (In press).

- Bazemore A. Sailing the 7Cs: Starfield revisited as a foundation of family medicine residency redesign. Fam Med. 2021; 53 (In press).

- deGruy F, McDaniel S. Proposed requirements for behavioral health in family medicine residencies. Fam Med. 2021;53 (In press).

- Austad K. Family medicine’s critical role in building and sustaining the future of hospital medicine. Fam Med. 2021;53 (In press).

- Barr WB. Women deserve comprehensive primary care: the case for maternity care training in family medicine. Fam Med. 2021. (In press).

- Wheat SJG. Community: the heart of family medicine. Fam Med. 2021;53 (In press).

- Bartell S. Multimorbidity in resident education. Fam Med. 2021;53 (In press).

- Gravel J. Professionalism in an era of corporate medicine. Fam Med. 2021;53 (In press).

- Schmitz D. The role of rural GME in improving rural health and health care. Fam Med. 2021;53 (In press).

- Misra S. Osteopathic prinicples and practice. Fam Med. 2021;53 (In press).

- Arenson C. The importance of interprofessional practice in family medicine residency education. Fam Med. 2021; 53 (In press).

- Elliott T. How do we move the needle?: Building a framework for diversity, equity, and inclusion within graduate medical education. Fam Med. 2021;53 (In press).

- Edje L. Training future family physicians to become master adaptive learners. Fam Med. 2021;53 (In press).

- AFMRD Survey on ACGME Program Requirement Revisions. 2020. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5ef55bb3b8ab0958a88de0ac/t/5f613e96038ef679ebb3881f/1600208535779/AFMRD+Survey+on+ACGME+Program+Requirement+Revisions.pdf. Accessed May 1, 2021.

- Starfield Summit IV: Re-Envisioning Family Medicine Residency Education Community Dialogue. https://residency.starfieldsummit.com/community-dialogue. Published 2020. Accessed May 1, 2021

- Re-envisioning Family Medicine Residency Education: Faculty. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/5ef55bb3b8ab0958a88de0ac/t/5fdb81a8dc9a6b6cb05a24b0/1608221096476/Faculty_All_201214_.pdf. Published 2020. Accessed May 3, 2021.

- Neutze D, Hodge B, Steinbacher E, Carter C, Donahue KE, Carek PJ. The Practice is the curriculum. [published online ahead of print May 10, 2021]. Fam Med. 2021. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.154874

- Lehmann C, Liao W. The patient voice: participation and engagement in family medicine practice and residency education. [published online ahead of print May 10, 2021]. Fam Med. 2021. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.327569

- Hoekzema GS, Cagno CK. A wealth of data, a paucity of outcomes: what can we learn from the ACGME Accreditation Data System? [published online ahead of print May 10, 2021]. Fam Med. 2021. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.277492

- Hodges BD. A tea-steeping or i-Doc model for medical education? Acad Med. 2010;85(9)(suppl):S34-S44. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181f12f32

- Holmboe ES. The transformational path ahead: competency-based medical education in family medicine. [published online ahead of print May 17, 2021]. Fam Med. 2021. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.296914

- Saultz J. Competency-based education in family medicine residency education. [published online ahead of print May 17, 2021]. Fam Med. 2021. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.816448

- Allen S. Learning from the implementation of milestones. [published online ahead of print May 17, 2021]. Fam Med. 2021. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.825433

- Fowler N, Lemire F, Oandasan I, Wyman R. The evolution of residency training in family medicine: a canadian perspective. [published online ahead of print May 17, 2021]. Fam Med. 2021. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.718541

- Douglass AB, Barr WB, Skariah JM, et al. Financing the fourth year: experiences of required 4-year family medicine residency programs. Fam Med. 2021;53(3):195-199. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.249809

- Eiff MP, Ericson A, Uchison EW, et al. A comparison of residency applications and match performance in 3-year vs 4-year family medicine training programs. Fam Med. 2019;51(8):641-648. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.558529

- Carney PA, Ericson A, Conry CM, et al. Financial considerations associated with a fourth year of residency training in family medicine: findings from the Length of Training Pilot Study. Fam Med. 2021;53(4):256-266. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.406778

- Woolever DR. The case for 3 years of family medicine residency training. [published online ahead of print May 26, 2021]. Fam Med. 2021. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.222197

- Newton WP, Magill MK. What family medicine can learn from other specialties. [published online ahead of print May 26, 2021]. Fam Med. 2021. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.976389

- Zakrajsek T. Developing Effective Lectures. Vol 1. Washington, DC: American Psychological Society; 1998.

- Zakrajsek T. All Learning Is An Active Process: Rethinking Active/Passive Learning Debate. The Scholarly Teacher (Blog). https://www.scholarlyteacher.com/post/all-learning-is-an-active-process. Published November 23, 2016. Accessed May 28, 2020.

- Zakrajsek T. Reframing the lecture versus active learning debate: suggestions for a new way forward. Edu Hlth Prof. 2018;1(1):1. doi:10.4103/EHP.EHP_14_18

- Zakrajsek T, Newton WP. Promoting active learning in residency didactic sessions. [published online ahead of print May 26, 2021]. Fam Med. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.894932.

- Garvin R, Carney PA. Balancing innovation and standardization in family medicine residency training: what should the future look like? Fam Med. 2021;53 (In press).

- Clements D. Milestones in family medicine: lessons for the specialty. Fam Med. 2021;53 (In press).

- Peterson L. Using the Family Medicine National Graduate Survey to improve residency education by monitoring training outcomes. Fam Med. 2021; 53 (In press).

- Carek P. Ongoing self-review and continuous quality improvement among family medicine residencies. Fam Med. 2021;53 (In press).

- Boelen C, Heck J; World Health Organization. Defining and Measuring the Social Accountability of Medical Schools. Geneva; World Health Organization; 1995. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/59441/WHO_HRH_95.7.pdf?sequence=1. Accessed November 19, 2020.

- Newton W, Wouk N, Spero JC. Improving the return on investment of graduate medical education in North Carolina. N C Med J. 2016;77(2):121-127. doi:10.18043/ncm.77.2.121

- Committee on the Governance and Financing of Graduate Medical Education, Board on Health Care Services, Institute of Medicine. Graduate Medical Education That Meets the Nation’s Health Needs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2014. https://www.nap.edu/read/18754/chapter/1. Accessed April 1, 2019.

- Kaufman A. Social accountability and graduate medical education. Fam Med. 2021;53 (In press).

- Park Y. My vision for family medicine. Fam Med. 2021;53 (In press).

- Wilson S. Three T’s to enable achieving the additional C required of family medicine educators. Fam Med. 2021;53(In press).

- Jabbapour Y. Diversity in the family medicine workforce. Fam Med. 2021;53 (In press).

- Harper D. Family medicine researchers – why? who? how? when? Fam Med. 2021;53 (In press).

- Muramoto M. Leadership development for the future of family medicine: training essential leaders for health care. Fam Med. 2021;53 (In press).