This paper reflects a vision of how family medicine residency training will be redesigned to prepare graduates to meet the health care needs of their patient populations and regional communities. Family physicians are needed to serve as personal physicians and as the patient’s usual source of care, as recognized in historic documents that have defined the specialty’s enduring role in society as the foundation of the health care system.

Modern residency practices will include residents as junior partners and members of multidisciplinary faculty teams. Residency practices will measure and improve care consistent with the triple aim: enhancing the experience of care for patients, improving outcomes of care for populations, and reducing waste and the cost of care in the system.

Curricula will include core elements of the roles of family physicians, including the development of therapeutic relationships with patients and families, recognizing patients’ needs and expectations, professionalism, the identification and management of acute and chronic illness, maternity care, and the care of hospitalized patients.

Also included will be emerging expectations of family physicians, including team roles, expanded care through telehealth and patient portals, identifying and intervening in modifiable social determinants of health, addressing structural racism, closing gaps of inequitable care for their patient populations, managing addiction as a treatable chronic illness, improving performance through clinical data registries, personalized medicine, and leadership. Wellness and assurance of a satisfying career will be a priority focus of preparation for career-long practice. Residents will become competent in the comprehensive scope of practice needed to serve in the role of continuous personal physician on multidisciplinary teams that serve as the usual source of care for populations in regions where the residencies are located.

“General practice is (and ever shall be) for general practitioners…. Thus, general practice…has been preserved for posterity….”1

“Every individual should have a personal physician who is the central point for integration and continuity of all medical and medically related services to his patient…. His [sic] concern will be for the patient as a whole, and his relationship with the patient must be a continuing one.”2

“What is wanted is comprehensive and continuing health care…. A different kind of physician is called for…. We suggest that he be called a primary physician.”3

“Medicine needs a new kind of specialist, the family physician who is educated to provide comprehensive personal health care.”4

“Our vision is to transform the health of our country, not just its medical care. A robust family medicine foundation is necessary but not sufficient to achieve this vision.”5

“We can insist that family medicine take its rightful place as the foundation of a high-quality health care system, a system that serves the needs of everyone. We can achieve these things … ‘by force of our demands, our determination and our numbers.’”6

The challenges currently facing health care in the United States need family medicine to again be the solution. Family medicine was conceived of American society’s call for the profession of medicine to dedicate its newest family member to altruism, and born embodying that aspect of professionalism which puts the needs of patients, populations and communities first. In 1966, three seminal reports, all external to the specialty, were published which created the new discipline of family medicine to meet the health and health care needs of American society. 2-4

Family medicine is the incumbent specialty in primary care, yet family medicine will always be a reform movement. While the core role of the family physician is enduring, the environment continually demands that newly identified needs be addressed and newly recognized challenges be met. Family medicine is a change agent on which society has repeatedly called, even if it was called by different names, and even if society did not always recognize that family medicine had previously responded to the call. Family medicine identifies as generalists, personal physicians, primary physicians, family physicians, and the foundation of the health care system.

Now family medicine is again being called upon, with expectation and hope, to assure that quality health care and population health are delivered in an affordable system. Family medicine will again respond because FM has a culture of servant leadership. The specialty of family medicine recognizes that to meet the new challenges, it is time to re-envision medicine, specifically through re-designing family medicine residency training at this time. This is family medicine’s vision for the future.

It is time for family medicine to own our vision, to assert leadership and take full responsibility for putting the vision of family medicine into practice. We will not succeed if we call upon and wait for others to create conditions we believe may be required to enable our vision to become reality. While we do not have control over the entire health care delivery system and therefore cannot control all aspects of the current practices of family physicians, we will start with changing our residency programs, and the accreditation requirements thereof.

“Health professions education has not kept pace with ‘changes in patient demographics, patient desires, changing health system expectations, evolving practice requirements and staffing arrangements, new information, a focus on improving quality, or new technologies.’”13

“Family medicine will transform health care, starting with our own ‘grass roots’ residency practices, pushing the system to change.”14

“Changes in both the practice environment and in residency education since the specialty was created have resulted in a need to re-evaluate and revise the traditional family medicine training model.”8

For decades, the US health care system has persistently ranked lower in international measures of quality and higher in costs than other nations.15 The United States remains the only developed nation in which a portion of the population is uninsured.16 In response, the current foci of the health care delivery system in the United States are often referred to as the triple aim: enhancing patients’ experiences of care, improving outcomes for populations, and reducing the cost of care in the system. These aims define the concept of value in health care. Emerging from the game-changing 2001 Institute of Medicine Quality Chasm report,17 the triple aim was first identified by Don Berwick and others at the Institute for Healthcare Improvement.18 These goals were then integrated into the payment policies of the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) beginning in 2010 during Berwick’s tenure as CMS administrator,19 and incorporated into the National Quality Strategy, promulgated in 2016 by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ, https://www.ahrq.gov/workingforquality/about/nqs-fact-sheets/fact-sheet.html). It is through addressing the triple aim that family medicine will meet the service, quality, and cost goals for patients and for the population.

To Enhance Patients’ Experience of Care…

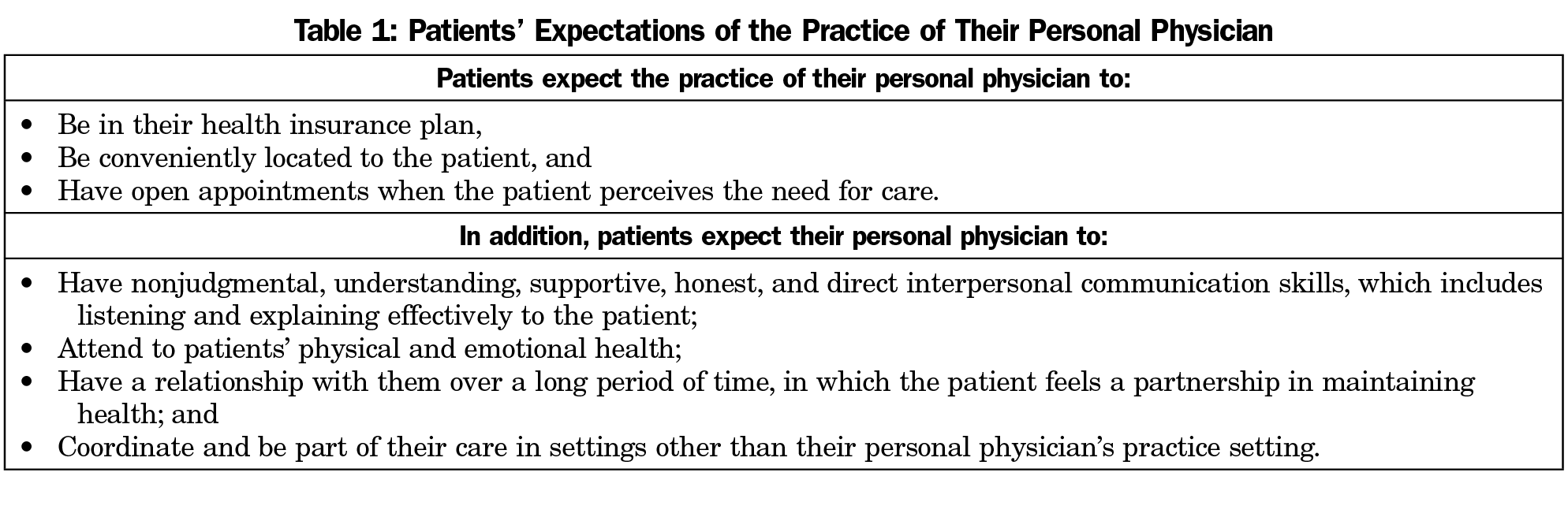

Residents will learn that patients’ experiences of care focus on their personal physician’s accessibility, communication skills, and recognition of the patient’s physical and emotional health (Table 1).20

At the same time, patients struggle to understand concepts such as comprehensiveness and quality.12 Family physicians deliver on the primary care promise of comprehensive care when they provide care in which they are trained and competent, and arrange and coordinate care to be delivered by others when the patient needs care that is beyond the knowledge and skills of the family physician.

Lacking the ability to measure quality, most patients assume that they are receiving quality care. Patients in residency practices will serve as partners in their care, ranging from shared decision making21 in their own care, to participating in reviewing and advising on the performance of the practice in achieving the triple aim. In this way, the patients of the practice will come to learn how to measure and recognize quality of care. Representatives of the community served by the practice, including patients of the practice, will participate in the governance of the practice.

To Improve Outcomes of Care for Populations…

Faculty role models will nurture residents’ natural curiosity for the evidence that underlies their choices of interventions for their patients.

Gaps often persist between our health care practices and what is most effective. These gaps are closed through using the tools of population health, including practice-based research, clinical guidelines, performance measures, data warehouses, clinical data registries, and performance reports. Faculty will model the use of these tools as core elements of the residency practices. All family medicine residency practices will use clinical data registries and performance reports to monitor and facilitate their achievement of improved outcomes of care for their patient populations.22

To Reduce Waste and the Overall per Capita Cost of Care in the System…

Through modeling by faculty during patient care and through structured learning, residents will become aware of the complexities of determining costs versus charges, what insurance plans will pay versus copays and deductibles, and resultant burdens to patients that serve as barriers to adherence. As part of shared decision-making, residents will learn to incorporate inquiry about what patients can afford. Residents will also learn what factors impact the cost of care to the system, including utilization, limiting unnecessary referrals, meeting patients’ needs outside of the emergency room, prevention of hospitalizations, and preventing readmissions through immediate and ongoing follow up of patients in the practice.23

The Residency Practice as the Curriculum

“For a noble purpose as complex as improving health and health care, real change actually happens by taking risks and learning together.”7

“You must be the change you wish to see in the world.” (Attributed to Mahatma Gandhi)

Family medicine will create interprofessional and collaborative residency practices (residents, faculty, team members, patients) that will function as the health care delivery system designed to meet the ongoing and emerging needs of their local and regional patient populations.8 These residency practices will hold themselves accountable to their communities to continually measure their progress toward meeting the identified needs of their patient populations.

Family medicine residencies will welcome new residents as new members of their practices. Residents will be oriented on how the care and learning model they just joined is designed and functions to meet the needs of the patient population served by the residency, as well as that of the institution and community. Since the majority of family medicine graduates will practice within 100 miles of where they train,9 it is reasonable during residency to practice and learn in a manner that will prepare residents for regional practice as family physicians, as well as to adapt to the changing needs of their patient populations and communities. Family medicine residents will be specifically recruited, and then expected to learn the necessary knowledge, skills, and attitudes to enter a career of serving their community as a personal physician and usual source of care.10,11

While subspecialties are defined by their content, family medicine is primarily a context-based specialty, managing the needs of patients in an environment of increasing complexity. As residents join the residency practice, they will begin developing relationships with their patients and learning the processes of care in their new practice, supervised by faculty teams. Continuity of relationships with patients is communicated as the core principle of being a family physician, as are first contact and comprehensive care.12 The residents will join the faculty and team members as partners in the practice in which all practice members will model these enduring core values of family medicine. Team members will reflect the added value of contributing roles in the delivery of primary care, including full- or part-time physicians, nurses, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, clinical pharmacists, social workers, public health officers, behavioral health faculty, nutritionists, patient educators, community health workers, and others.

Fulfilling the core principle of continuity, residents will participate in the care of their patients in whatever settings their patients receive their care: in the family medicine ambulatory practice, through telehealth, via asynchronous patient portals, through necessary consultations, in the hospital, in labor and delivery settings, in surgery, in nursing homes, and at home. Patients of these practices will experience their personal physician as “being there for them” in all their health care, even if another physician in another setting is temporarily managing the patient’s care. In addition to being there, residents will learn to coordinate the care of their patients in various settings.

Core and Emerging Curricular Elements

“Given the changes taking place in the specialty and within the broader health care system, it is clear that the traditional family medicine curriculum, although successful in the past, cannot meet the needs of the future.”24

Specific attention will be given to preparing residents to meet today’s and tomorrow’s needs of local and regional patient populations. Many patient expectations are enduring, such as for ongoing trusted relationships between patients and their personal physician and addressing patients as whole people with integrated physical and mental health needs.

Early in their new continuity practice, residents will have the opportunity to arrange—with the guidance of faculty mentors—in-depth learning experiences in other medical, public health, and community settings. These additional learning experiences will be specifically designed to best prepare residents to serve as comprehensive primary care physicians to meet the needs of the patient populations of the institution, community, or region. The residents’ continuity practices with their panel of patients will be maintained, albeit at times reduced, during additional in-depth learning experiences.

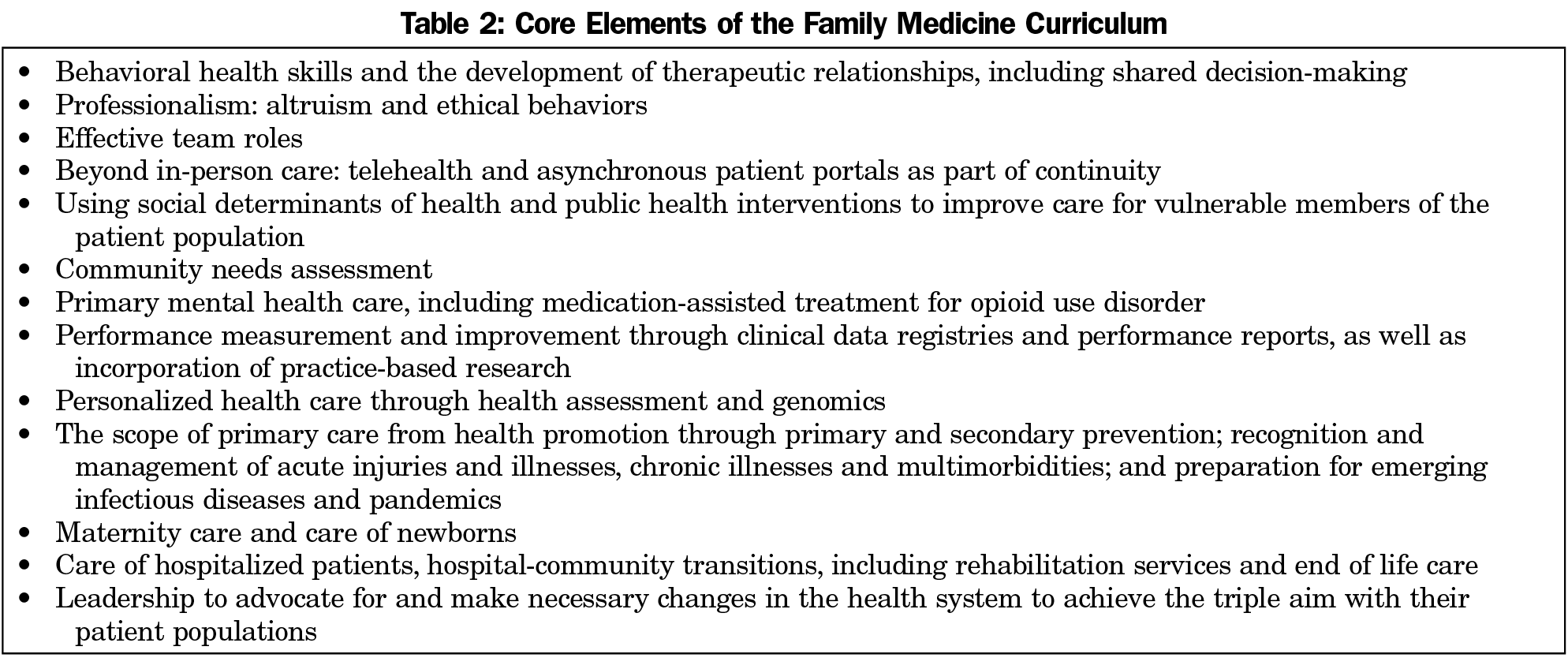

Residency practices will assure that residents have experiences and achieve knowledge and skills in both enduring and emerging elements of primary care (Table 2). Residency practices will model and teach the use of new tools to facilitate successful primary care practice:

- Office technology is evolving, such as using point-of-care ultrasound. Family physicians will enhance the experience of care for their patients beyond office-based visits through telehealth25 and ongoing communication with patients asynchronously through patient portals.

- Genetically-based treatments are anticipated to become more available as all physicians enter the future of personalized medicine.26

- The challenge to effectively address opioid use disorder as a chronic illness for which there are effective treatments27,28 persists in large part from the War on Drugs, a term popularized in 1971, which codified a judgmental view of drug addiction as criminal and sociopathic behavior. Residents will learn to use behavioral therapies in conjunction with medication-assisted treatment as tools in their practices to successfully manage and intervene in the chronic illness of opioid use disorder.29, 30

We commit that family physicians will be prepared to address current additional challenges, which have been either frustratingly persistent or steadily growing in importance:

- Research into diagnostic and therapeutic aspects of medical care has eclipsed the role of social determinants of health.31 Residency practices will support the experience of residents learning about the social determinants of health and effective interventions in community settings.

- Persistent inequities of care persist for people with disabilities. Inequities also manifest as racial, ethnic, language, and class disparities that are not limited to the urban core.32 Structural racism has been identified as an underlying contributor to inequities of care and must be addressed during the training of family physicians. Gaps in the processes of care for patients violate the triple aim. No one specialty can address disparities in care across the system. Generalists who care for patient populations, particularly family physicians and their practice teams, will be called upon to advocate for and accept this set of population-based challenges. Residency practices will be designed, and residents will learn to model successful approaches to identifying and closing care disparity gaps.

- The fragmented US health system continues to deliver inequities in care and outcomes for populations which remain geographically isolated from needed care. For example, many areas are maternity care deserts with a lack of maternity care providers and no hospital offering obstetric care.33 Family centered maternity care will be a part of the training of all family physicians and a substantial element of such training when practicing maternity care will be a core part of their practices in their communities.34

- An aging population brings with it people who develop and live with multiple chronic illnesses. The newly coined term “multimorbidity” calls attention to an historically recognized and currently central role of family physicians to manage over time their patients with multiple chronic conditions.35

- While COVID-19 may be a once-in-a-hundred-year pandemic, the population has been threatened repeatedly by other epidemics of emerging infectious diseases, including such recent examples as HIV-AIDS, Zika and Ebola.36 While experts in infectious diseases and public health are required to address these repeated epidemics, primary care is where people affected by epidemic diseases will present. Therefore, family medicine residency practices will be prepared and will prepare graduates.

Residents will be graduated from the residency program when they demonstrate that they have met the goals and objectives of the training program, are deemed to be competent family physicians who are prepared to serve their patients populations as personal physicians and as their patients’ usual source of care, and who have completed at least 3 years of residency practice and training. Both competency and time of experience are valid measures to determine successful completion of training and readiness for their next stage of practice.

Assuring Satisfying Careers

“The principal driver of physician satisfaction is the ability to provide quality care.”37

Since “burnout among the health care workforce threatens patient-centeredness and the triple aim,” residency practices will prioritize the well-being of its practice partners. Faculty will model and residents will participate in interventions designed to promote clinician well-being. This focus on well-being has been incorporated into the concept referred to as the quadruple aim.37

The residency practice will recognize and address elements of the practice system that result in obstacles to the ability to provide quality care. After first addressing frustrations in the practice system, residents will be encouraged and supported to implement personal wellness interventions, such as mindfulness, meditation, exercise, and other interventions that have been demonstrated to be useful in facilitating mental wellness and avoiding burnout. System and practice interventions must be addressed, however, before personal interventions can be expected to be successful.38

Upon being accepted into the residency, residents will be matched to faculty mentors who will guide the new resident members of the practice through orientation to the care and learning system, building the resident’s curriculum, knowledge and skill acquisition, formative performance review, and prioritizing personal wellness. These mentors will continue to be available to residents after graduation to help mentees continue to develop and implement a plan for lifelong learning, including advances in medicine, but also seeking opportunities to learn new skills to enhance the ability of their practices to achieve the triple aim with their patient populations and in their communities.

Medical students will be inspired to seek educational experiences that display the satisfaction and excitement of resident practice partners who successfully develop rewarding ongoing relationships with patients, provide comprehensive care, and demonstrate measurable, continuous progress in achieving the triple aim. It can be expected that medical students will then seek to join a family medicine residency practice as a new partner.

Residency practices will model lifelong learning for family physicians.39 Ongoing personal development will include a commitment to service, personal wellness and growth. Professional development will include self-evaluation and attention to the tasks of career stages, including skill building, practice building, leadership, governance, and mentoring. Scholarship will include practice-based research, evidence-based reviews, and translation of knowledge and practice guidelines into primary care relevance.

As residents transition into their communities of practice, they should serve as extensions of the residency practices of the sponsoring institution into the community and region. This multiplies sites for resident experiences, increases faculty role models, and enhances the resources available to the community practices to achieve the triple aim by being linked to the residency practices and sponsoring institution.

“The challenge now facing family medicine is to take the initiative for change, engage others truly committed to reform, and to see the process through—in all its complexities and risks—to a successful conclusion.”8

Family medicine residency practices will initiate a new reputation for the specialty40:

- Family physicians will model satisfying and rewarding careers, with continuous intellectual stimulation, a sense of being of service, making a difference in the lives of patients and communities and enjoying professional and financial security.

- Other health professionals, including team members and consultants, will view family physicians with professional respect and esteem, recognizing that family physicians have a reputation for quality care, satisfied patients, and effective collegial communication among health professionals.

- Payers will see family medicine practices serving as the patient’s medical home, delivering accessible, 24/7/365, comprehensive, continuity, coordinated, and efficient, and affordable care for patients in the practice.

- Medical students will see family physicians serving as positive role models, providing technologically advanced care, receiving positive feedback from patients regarding relationships and care and enjoying career satisfaction.

- Communities will recognize family physicians as partners in public health, adapting to the needs of the community as they arise.

- Patients will choose a family physician as their personal physician, and the family physician’s practice as the patient’s personal medical home and their usual source of care. In so doing, patients will be assured that their family physician will establish an ongoing relationship with them, be available to meet their health care needs, will listen and explain, will stay current, will incorporate appropriate technology to improve their care effectively and efficiently, will demonstrate a whole-person approach to their care over time, and will advocate for the patient and their family members in the health care system.

Acknowledgments

Disclosures: The author’s career has included relationships, experiences, and perspectives that might be perceived by others as resulting in biases.

The author trained in an early family medicine residency that was designed to prepare graduates to meet the needs of the underserved population in the local urban community. He then practiced full-scope family medicine in a rural community with one medical office, 100 miles from his residency.

The author served as director of both a community-based and academic health center-based family medicine residency, as well as director of a university-affiliated network of predominantly rural family medicine residencies. He worked for the American Academy of Family Physicians and served as staff executive for the Future of Family Medicine project (2002-2004). He spent a decade leading the Council of Medical Specialty Societies, which focused on professionalism and performance improvement in practice.

The author currently teaches health system science, professionalism, and leadership to graduating family medicine residents in each of the three family medicine residencies in his local community. He is a member of the Advisory Board for the Center for Professionalism and Value of the American Board of Family Medicine.

The author has for the past 8 years received his own personal health care from an academic family medicine residency program. His personal primary care physician is a resident who changes every 3 years.

The plans described in this article reflect the vision of family medicine that has evolved from the seminal reports of 1966 (Millis, Willard, Folsom), through the publications of the Future of Family Medicine project in 2004, Family Medicine for America’s Health in 2015, and many intercedent publications. All of these remain relevant. Society’s need for the role of the family physician as the generalist personal physician is enduring.

Acknowledgment: The author acknowledges Warren Newton, MD, MPH, for his suggestions to improve this paper.

References

- Fox TF. The personal doctor and his relation to the hospital. Observations and reflections on some American experiments in general practice by groups. Lancet. 1960;1(7127):743-760. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(60)90632-2

- Folsom M; National Commission on Community Health Services. Health is a Community Affair—Report of the National Commission on Community Health Services (NCCHS). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press; 1967.

- Millis J; Citizens Commission on Graduate Medical Education. The Graduate Education of Physicians. The report of the Citizens Commission on Graduate Medical Education. Chicago: American Medical Association; 1966:36-37.

- Willard WR; AMA Ad Hoc Committee on Education for Family Practice of the Council on Medical Education Meeting the Challenge of Family Practice. The Report of the Ad Hoc Committee on Education for Family Practice of the Council on Medical Education. Chicago: American Medical Association; 1966.

- Stream G. Family medicine’s agenda to make health primary. Fam Med. 2015;47(8):595-597.

- Stewart A. AAFP Presidential Inaugural Address, 2020

- Hall MN, Brungardt SH. Owning the FMAHealth vision. Fam Med. 2015;47(8):655-657.

- Martin JC, Avant RF, Bowman MA, et al; Future of Family Medicine Project Leadership Committee. The Future of Family Medicine: a collaborative project of the family medicine community. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 1):S3-S32. doi:10.1370/afm.130

- Fagan EB, Gibbons C, Finnegan SC, et al. Family medicine graduate proximity to their site of training: policy options for improving the distribution of primary care access. Fam Med. 2015;47(2):124-130.

- Coutinho AJ, Cochrane A, Stelter K, Phillips RL Jr, Peterson LE. Comparison of intended scope of practice for family medicine residents with reported scope of practice among practicing family physicians. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2364-2372. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.13734

- Peterson LE, Fang B, Puffer JC, Bazemore AW. Wide gap between preparation and scope of practice of early career ramily physicians. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(2):181-182. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.02.170359

- (Ref: Bazemore’s new redesign paper in this publication)

- Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Health Professions Education Summit; Greiner AC, Knebel E, editors. Health Professions Education: A Bridge to Quality. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2003. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK221528/. Accessed April 13, 2021.

- Borkan J, James P, Mazzone M, Kuzel A. FMAHealth and academic family medicine: on the frontlines or on the sidelines? Fam Med. 2015;47(8):652-654.

- Tikkanen R and Abrams MK. US health care from a global perspective, 2019: higher spending, worse outcomes? The Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2019. Published January 30, 2020. Accessed April 13, 2021.

- Vladeck B. Universal health insurance in the United States: reflections on the past, the present, and the future. Am J Public Health. 2003;93(1):16-19. doi:10.2105/AJPH.93.1.16

- Crossing the Quality Chasm. A New Health System for the 21st Century; Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on Quality of Health Care in America. Washington (DC). US: National Academies Press; 2001.

- Berwick DM, Nolan TW, Whittington J. The triple aim: care, health, and cost. Health Aff (Millwood). 2008;27(3):759-769. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.27.3.759

- Berwick D. Address to the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid, America’s Health Insurance Plans – Medicare Conference. September 13, 2010, Washington DC

- Green LA, Graham R, Bagley B, Kilo CM, Spann SJ, Bogdewic SP, Swanson J. Future of Family Medicine Task Force 1: Report of the Task Force on Patient Expectations, Core Values, Reintegration, And the New Model of Family Medicine. Ann Fam Med 2004;2(Supplement 1):S33-S50 (p.S37)

- Barry MJ, Edgman-Levitan S. Shared decision making—pinnacle of patient-centered care. N Engl J Med. 2012;366(9):780-781. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1109283

- Dreyer NA, Garner S. Registries for robust evidence. JAMA. 2009;302(7):790-791. doi:10.1001/jama.2009.1092

- Friedberg MW, Hussey PS, Schneider EC. Primary care: a critical review of the evidence on quality and costs of health care. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010;29(5):766-772. doi:10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0025

- Bucholtz JR, Matheny SC, Pugno PA, David A, Bliss EB, Korin EC. Future of Family Medicine Task Force Report 2: Report of the Task Force on Medical Education. Ann Fam Med 2004;2(Supplement 1):S51-64 (p. S18)

- Alexander GC, Tajanlangit M, Heyward J, Mansour O, Qato DM, Stafford RS. Use and content of primary care office-based vs telemedicine care visits during the COVID-19 pandemic in the US. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(10):e2021476. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.21476

- Vogenberg FR, Barash CI, Pursel M. Personalized Medicine. Pharmacy and Therapeutics; 2010. Part 1 - Oct; 35(10):560-562, 565-567, 576. Part 2 – 35(11): 624-626, 628-631, 642. Part 3 – 36(12):670-671, 673-675

- Saitz R, Larson MJ, Labelle C, Richardson J, Samet JH. The case for chronic disease management for addiction. J Addict Med. 2008;2(2):55-65. doi:10.1097/ADM.0b013e318166af74

- Hser YI, Mooney LJ, Saxon AJ, et al. High mortality among patients with opioid use disorder in a large healthcare system. J Addict Med. 2017;11(4):315-319. doi:10.1097/ADM.0000000000000312

- Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration Center for Substance Abuse Treatment. Medication-Assisted Treatment. https://www.samhsa.gov/medication-assisted-treatment. Published 2020. Updated January 4, 2021. Accessed April 13, 2021.

- Medications for Opioid Use Disorder: For Healthcare and Addiction Professionals, Policymakers, Patients, and Families [Internet]. Rockville (MD): Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (US); 2018. (Treatment Improvement Protocol (TIP) Series, No. 63.) https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK535268/. Accessed April 13, 2021.

- Secretary’s Advisory Committee on National Health Promotion and Disease Prevention. Healthy People 2020: An Opportunity to Address Societal Determinants of Health in the United States. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services; Oct. 26, 2010.

- Egede LE. Race, ethnicity, culture, and disparities in health care. J Gen Intern Med. 2006;21(6):667-669. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2006.0512.x

- Rivett M, Skinner E, Bradford K. Boosting Maternity Care in Rural America. National Conference of State Legislatures: Legisbrief, Vol. 27, No. 39. https://www.ncsl.org/research/health/boosting-maternity-care-in-rural-america.aspx. Published November 2019. Accessed April 13, 2021.

- Nesbitt TS, Kahn NB, Tanji JL, Scherger JE. Factors influencing family physicians to continue providing obstetric care. West J Med. 1992;157(1):44-47.

- Navickas R, Petric VK, Feigl AB, Seychell M. Multimorbidity: what do we know? What should we do? J Comorb. 2016;6(1):4-11. doi:10.15256/joc.2016.6.72

- Morens DM, Fauci AS. Emerging pandemic diseases: how we got to COVID-19. Cell. 2020 Sep 3;182(5):1077-1092. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2020.08.021. Epub 2020 Aug 15.

- Bodenheimer T, Sinsky C. From triple to quadruple aim: care of the patient requires care of the provider. Ann Fam Med. 2014;12(6):573-576. doi:10.1370/afm.1713

- American Medical Association. Steps Forward. On-line modules on Burnout and Well-Being. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward/pages/professional-well-being. Published 2020. Accessed April 13, 2021.

- Jones WA, Avant RF, Davis N, Saultz J, Lyons P. Future of Family Medicine Task Force Report 3: Report of the Task Force on Continuous Personal, Professional, and Practice Development in Family Medicine. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 1):65-74. doi:10.1370/afm.136

- Dickinson JC, Evans KL, Carter J, Burke K. Future of Family Medicine Task Force Report 4: Report of the Task Force on Marketing and Communications. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 1):75-87. doi:10.1370/afm.137

There are no comments for this article.