Background and Objectives: Health professionals may face sexual harassment from patients, faculty, and colleagues. Medicine’s hierarchy deters response to sexual harassment. Current evidence consists largely of quantitative data regarding the frequency and types of sexual harassment. More information is needed about the nature of the experience and how or why professionals choose to report or respond.

Methods: We developed and administered a semistructured interview guide to elicit family medicine faculty and residents’ experiences with sexual harassment and gender bias. Facilitators led a series of focus groups divided by faculty (N=28) and residents (N=24). We ensured voluntary consent and groups were audiotaped, transcribed and deidentified. We coded the transcripts using immersion-crystallization theory to identify emergent themes.

Results: Sexual harassment from patients and colleagues was described as witnessed or personally experienced by faculty and resident participants in 100% of the focus groups. Respondents identified the presence of mentors, clear reporting process and follow-up, history of good organizational response to reporting, and education and training as facilitators to reporting sexual harassment. Barriers to reporting included fear of retaliation, lack of trust of the system to respond, lack of clarity about “what counts,” and confusion with the reporting process.

Conclusions: It is important to capitalize on facilitators to reporting sexual harassment, starting with acknowledging the frequency of sexual harassment and gender discrimination. Addressing barriers to responding through education and training for our learners and faculty is critical. Clarifying the reporting process, having clear expectations for behavior, and a continuum of responses may help increase the frequency of reporting.

Despite decades of awareness and antiharassment policies from national organizations, the rate of discrimination and harassment reported by medical trainees has not decreased over time.1,2 In a 2019 Massachusetts study of residents, 61% of participants reported personal experience with gender-based bias or discrimination during residency, including 93% of women, compared with 24% of men.3 Sexual harassment (SH) was experienced by one-third of the women surveyed. While women in this study commonly reported experiencing gender discrimination (GD) and SH, only 5% of the women had reported their experiences formally. Cortina and Berdahl attribute low rates of reporting to “fear of blame, disbelief, inaction, retaliation, humiliation, ostracism and damage to one’s career and reputation.”4

High-profile cases have heightened public awareness of SH and GD in the workplace5 including academic medicine.6-8 In a recent study, women clinician-researchers were more likely than men to report GD (n=1,066, 66.3% vs 9.8%) and to have experienced SH (n=1,066, 30.4% vs 4.2%).9 Power and hierarchy limits self- or bystander-report and response to incidents. Those who are most junior, eg, students, staff, residents and lower rank faculty, often fear reporting would result in retribution or risk to their careers10 with worse outcomes when the perpetrator has higher status.11 Additionally, aside from SH and GD by supervisors and colleagues, medical professionals also face SH from patients.

The current body of evidence focuses primarily on quantitative data, including frequency and types of experiences. One previous, small, narrative study focused on women trainees.12 A recent mixed-method study described the prevalence and impact of microaggressions on women surgeons and found that trainees and women in men-majority surgical fields reported the most frequent and severe bias.13 That study focused on GD and did not ask about SH experiences. Descriptions of lived GD and SH experiences of faculty and residents in women-majority fields such as family medicine are limited, as are descriptions of the response to such experiences.14 Following our university’s high-profile case,15 our team recognized the need to ascertain the barriers and facilitators to reporting and responding to GD and SH in our own department.

Setting, Participants and Protections

We conducted our study within our academic department of family medicine; the University of Rochester’s Institutional Review Board deemed this study exempt (RSRB00072684).

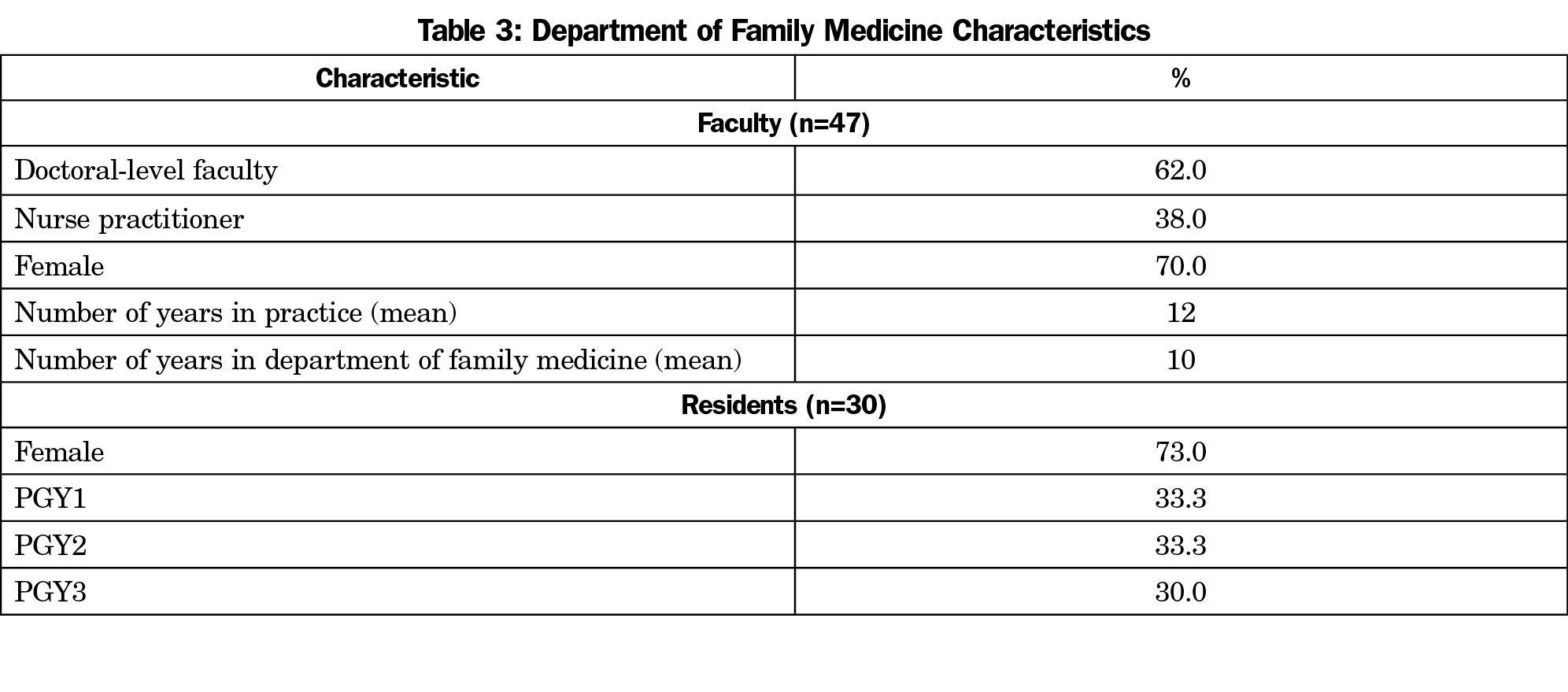

We provided information about the study at routine faculty and resident meetings and invited voluntary participation. We intentionally did not collect specific demographics to maintain privacy. More than half of total faculty and residents participated, with approximately equal numbers of residents and faculty.

Design

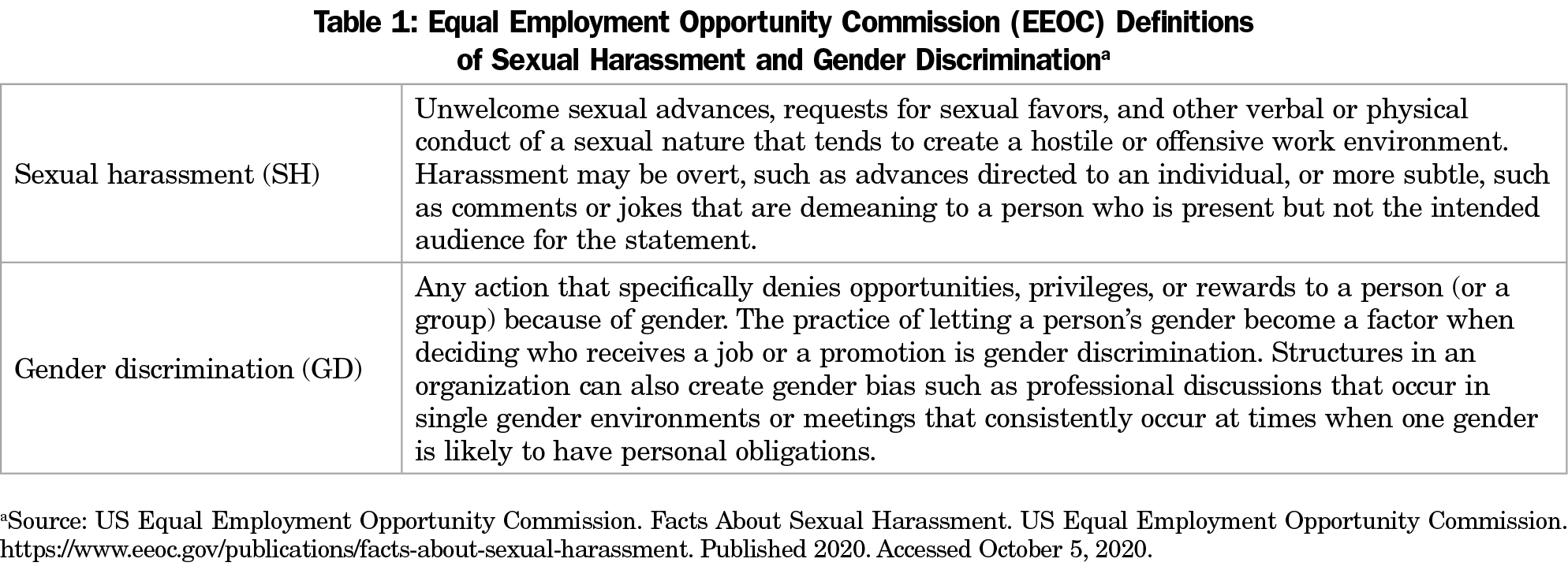

Based on the literature, we developed a semistructured interview guide to identify and characterize family medicine faculty and residents’ experiences of SH and GD and beliefs about responding to and reporting these incidents. We used the United States Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) definitions of sexual harassment and gender discrimination, which includes gender bias (Table 1).16 We divided participants by gender, as psychosocial factors were the goal of the study,17 allowing participants to self-select. None of the participants were gender nonconforming. Four focus groups (three groups of women and one of men) consisted of six to eight faculty of mixed seniority, including family physicians, nurse practitioners, and behavioral health faculty. Research team members facilitated faculty groups and chief residents (postgraduate year-4) facilitated the two resident groups to decrease the likelihood of power dynamics influencing responses. Previous experiences indicate that residents often do not feel comfortable discussing faculty behavior in front of other faculty. Members of the research and behavioral health team oriented the chief residents to the focus group guide and facilitation. Focus groups were audiotaped and transcribed by an external agency to maintain confidentiality. Voices were too similar to allow for speaker numbers. Focus groups for faculty consisted of two, 1-hour sessions per group and one, 2-hour session per group for residents.

Data Collection

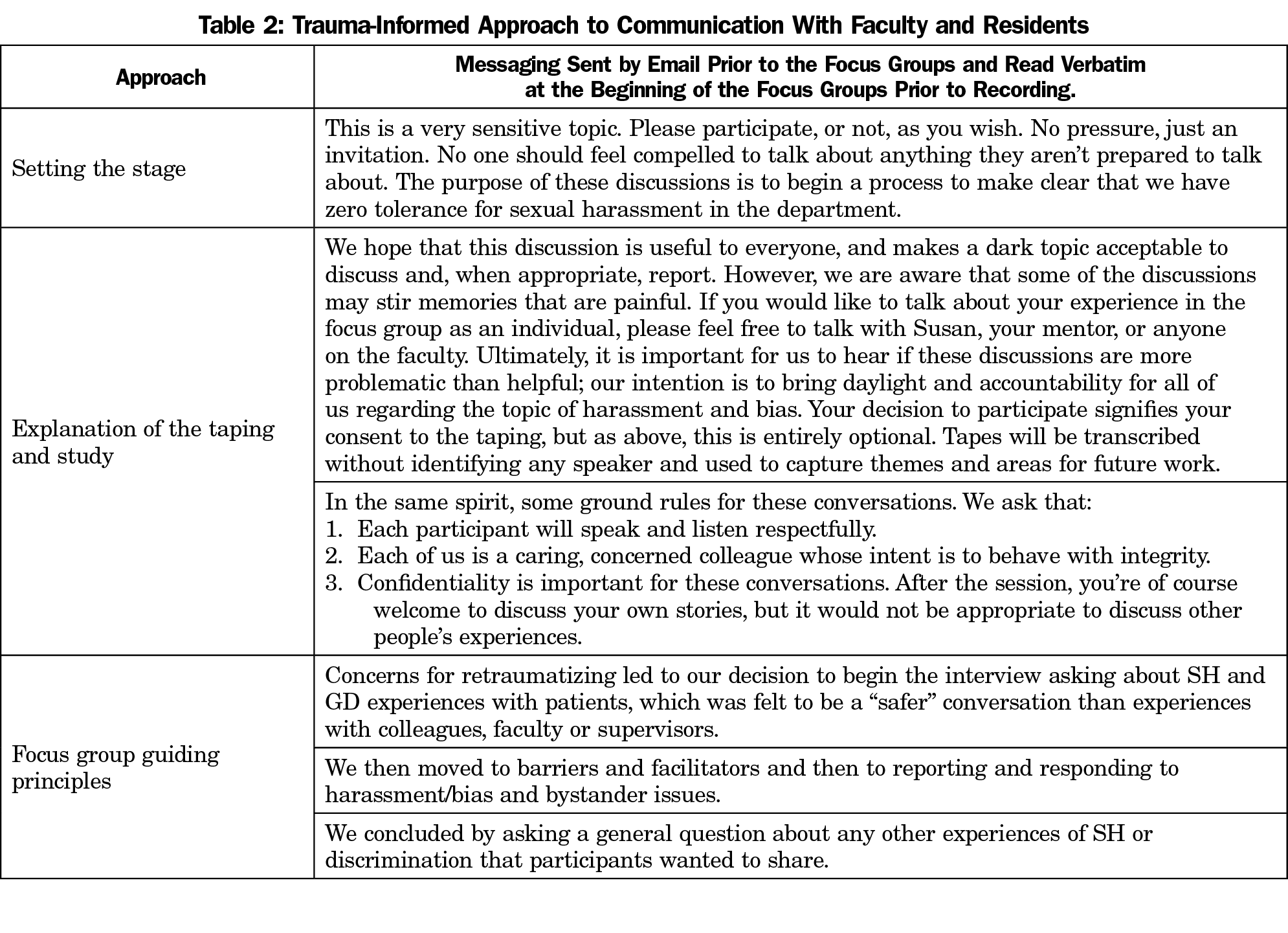

Facilitators began groups with a review of the consent for participation, assurance of anonymity and the expectation of confidentiality among participants. The interview guide defined SH and GD and included open-ended and follow-up questions about participants’ experiences. Our process was guided by a trauma-informed approach and prioritized the emotional safety of our participants (Table 2).18

Data Analysis and Identification of Codes and Categories

The study team (H.R., K.F., C.F., S.M.) used an immersion-crystallization approach to code the transcripts.19 Each transcript was independently coded by two study team members using MAXQDA software to organize and analyze codes. We considered a concept a code if it was noted more than once and present in at least two of the focus group transcripts. We grouped the codes into themes drawing from our clinical experience, background knowledge, and contextual information. The final coding structure was approved after four iterations, at which point we reached saturation and no new codes occurred in the data. We “member checked”20 the findings with our faculty, which confirmed the results. The focus group guide asked questions about lived experience and reporting and responding to SH and GD; this paper focuses on the analysis regarding reporting and responding.

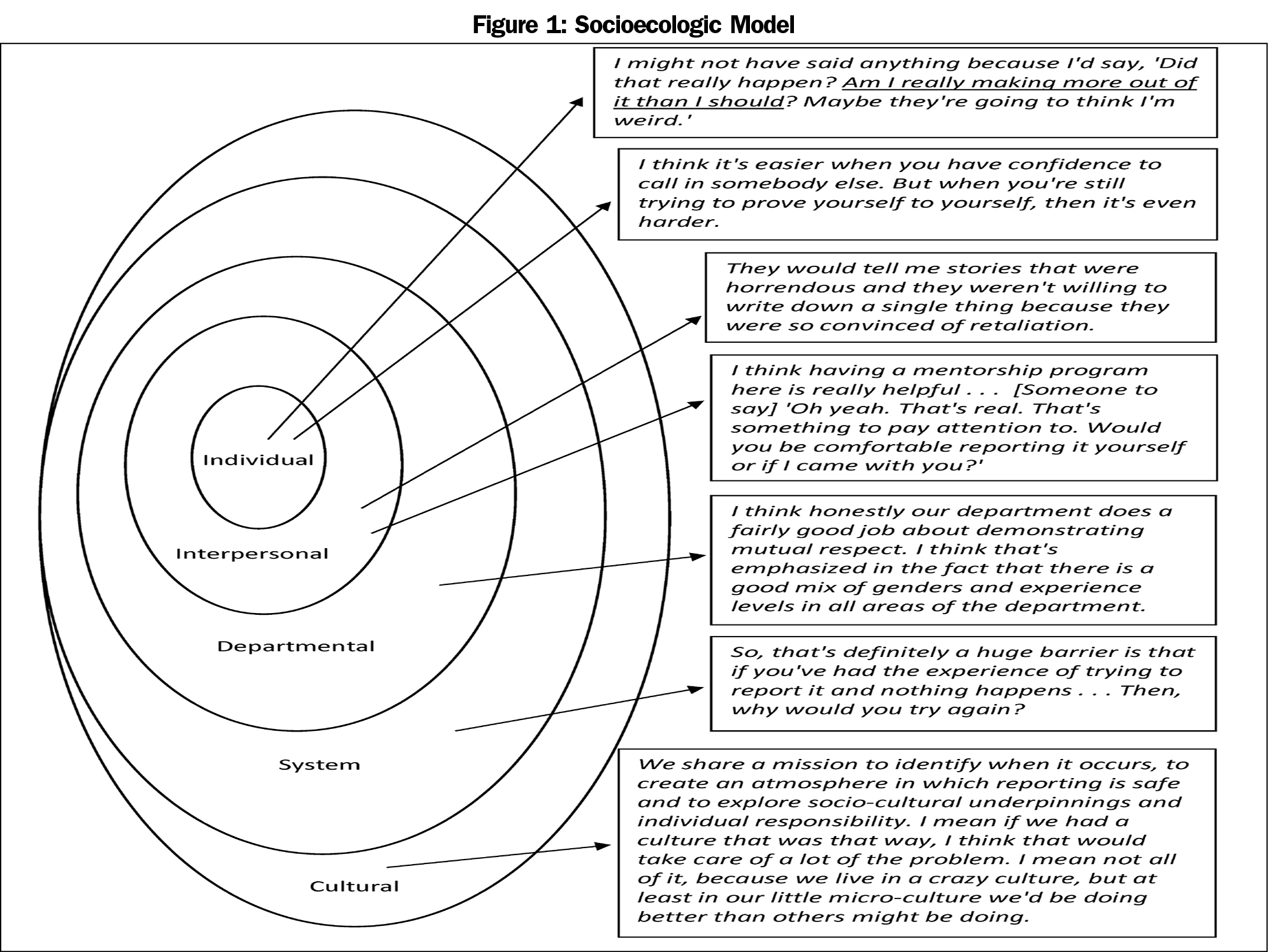

Our six focus groups consisted of 28 faculty and 24 residents (see Table 3 for an overview of the composition of our faculty). The participants of our focus groups, particularly women, reported frequent sexual harassment and gender bias from patients and colleagues. We found the barriers and facilitators to reporting and responding clustered into five interconnected levels of individual, interpersonal, department, system, and cultural themes. We used the Social Ecological model as a framework for understanding the results (Figure 1).21 There was some overlap between the response to SH from patients as compared to other SH and GD experiences, but there were also some key differences.

Barriers

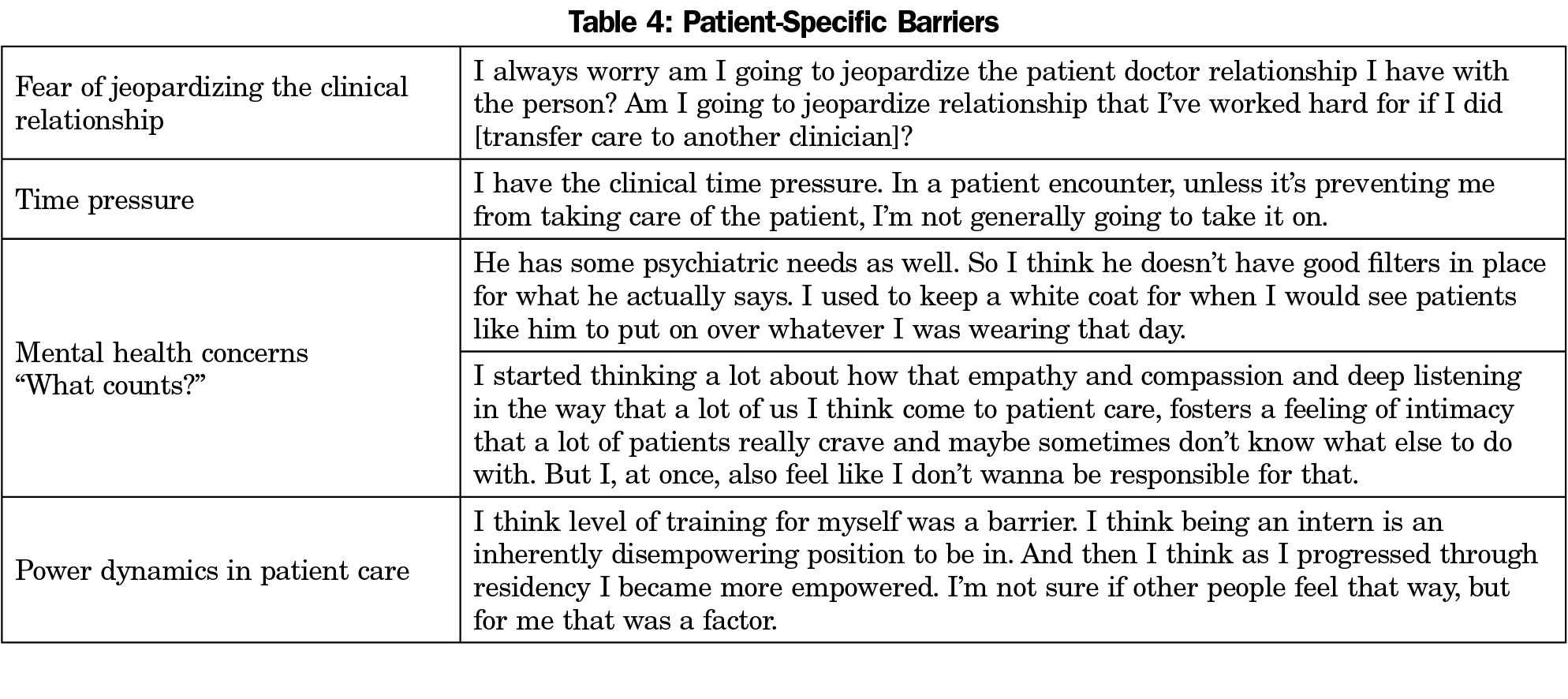

Fear of jeopardizing the doctor-patient relationship was one of the most frequently cited reasons that clinicians hesitated to respond to or report harassment from patients. For example, clinicians reported conflict between their commitment to patient care and their need to establish healthy boundaries regarding inappropriate patient behavior. Time pressure and the power dynamics of patient care represented additional barriers to responding to or reporting harassment from patients. Table 4 includes a more detailed list of patient-specific barriers.

. . . I think there’s a sense of futility. I’m sure that they do this everywhere. I see them for 20 minutes twice a year, what am I going to do during that time? I really don’t address it. I don’t because I’m afraid that if that’s my first interaction with the patient that it’s only gonna be negative from that point on.

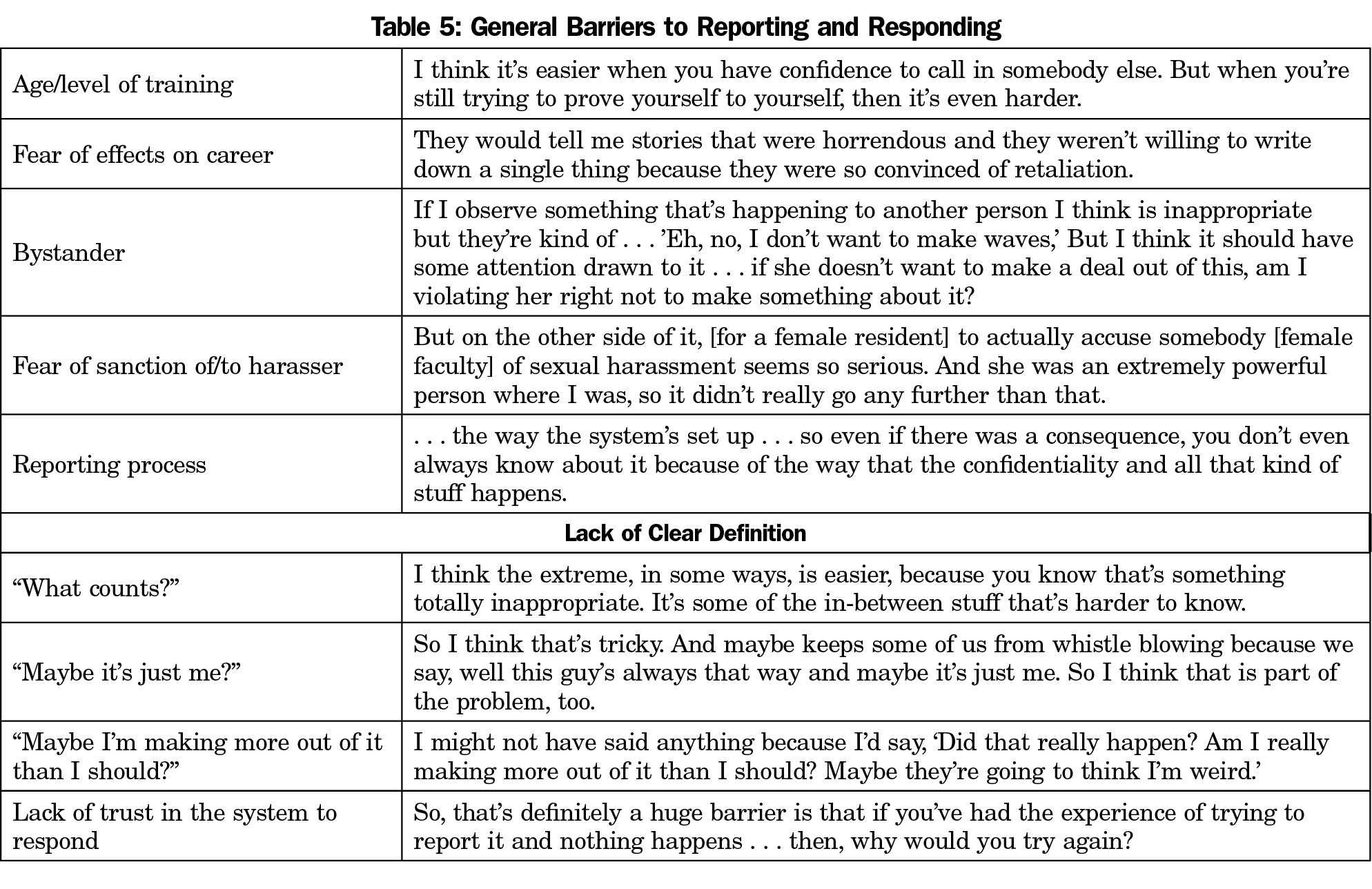

Both in patient care and in other work settings, participants noted the difficulty of discerning “what counts,” citing individual-level factors such as “age at the time” complicating their sense of which scenarios and behaviors constituted reportable offenses. Table 5 includes additional general barriers to reporting. Several participants noted traditional age hierarchies and socially expected “respect for elders” as a barrier to confronting patients’ harassing behavior.

. . . [I] think age is a barrier. There’s also a component of being female, but also if you’re talking to an older male or a female patient like arguing with them. You’re younger than they are.

Clinicians also noted the challenge of mental health comorbidities in patients with sexually harassing behavior; many clinicians reported a tendency to tolerate GD or SH from patients who had a psychiatric disorder.

The most common type of experience that I have is amongst my patients that have some mental health diagnosis, they just don’t really have a filter. They say things that are inappropriate. I feel like just generally we tolerate a lot from those kinds of patients on a lot of different types of behavior and say it’s part of their diagnosis.

One of the most frequently cited system-level barriers to action was the participant’s lack of trust in leadership to respond to reported incidents. This reflected personal experience with prior reporting or ongoing GD or SH with an offender who continued to practice and teach, despite the behaviors being known to senior leaders.

Same thing happened with the [attending] that I was working with. It was notorious. Everyone told me, “This is going to happen to you when you’re on the rotation” . . . and nothing was done about it.

Participants noted the system-wide lack of clarity and transparency about reporting and follow up as a barrier to reporting GD/SH. When a disciplinary response to GD/SH is protected by confidentiality rules, the original reporter may not be made aware of the outcome. Participants reported confusion about which incidents should be reported to whom; eg, whether there was a different process for patient- versus colleague-initiated harassment.

We’re trying to figure out what the reporting system is … and I can’t believe we haven’t sorted that out . . . I know that there is sort of a system, but I know if it’s not one that works or that people know about … It’s not really a good system.

Participants reported a continuum of interpersonal-level fear of reporting, from being seen as someone who “takes the fun out” of work, to losing opportunities for career advancement. Many participants worried about the potential effects on the person they were reporting, especially if he/she was a colleague or mentor.

I immediately thought, “But if I report and that person gets publicly shamed, that’s a problem.” Why is that a problem? They should be ashamed.

Participants who were bystanders to GD/SH noted individual- and interpersonal-level difficulties in responding to or reporting episodes they had witnessed, including wanting to avoid presumption that the victim was suffering from the experience. There was also concern that reporting something they witnessed, rather than experienced, was paternalistic.

[It has happened] dozens of times [while I am] precepting . . . I’ll say something like, “You’ve got a really good doctor,” and [patients] say, “She’s really hot, too,” or, “She’s really good looking,” or, “She dresses real nice,” . . . if I say something, does that mean, am I saying, “Oh, you’re not powerful enough to say something?” So am I disempowering women? But if I don’t say something, am I colluding?

Facilitators

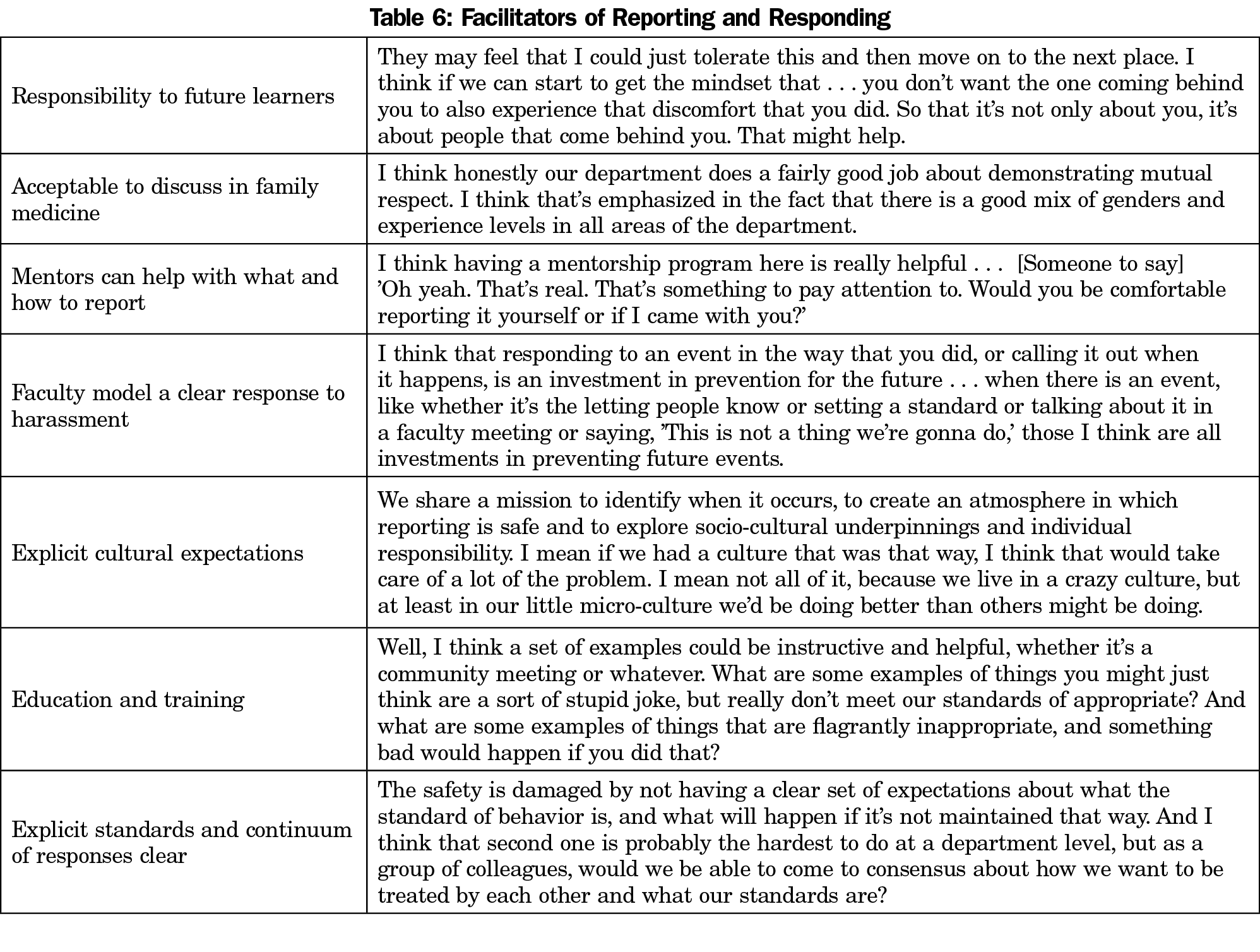

Facilitators of reporting and responding are detailed in Table 6. Participants noted the ease of sending electronic health record messages to the medical director as a system-level facilitator of reporting patient behavior. General facilitators in non-patient-care situations included department- and system-level education and training, explicit cultural expectations and standards for behavior, a known continuum of responses to violations in standards, and having seen a clear faculty response to witnessed harassment of a resident or student. Additional department-level facilitators to reporting were the availability of mentors both for junior faculty and for residents, the cultural acceptability of discussing harassment and bias, and an interpersonal-level feeling of duty to help those who come behind you. Many participants identified the opportunity to mirror processes we use for other behavioral standards in clinical medicine, such as those for patient privacy violations.

If one of our trainees has a HIPAA violation I have an algorithm for what I do with them. We talk about the offense, I refer them to certain education, they have to do something that demonstrates that they have taken in the information, and some sort of analysis of what happened relative to that thing.

Family medicine residents have the additional vulnerability of frequently rotating in other departments where residents perceive greater risk to speaking up about harassment. Participants recommended clear communication of expectations to learners rotating outside of the department, such as an email stating:

Just a reminder, we encourage our residents to tell us if they feel uncomfortable, or [have experienced] sexual harassment or gender bias [discrimination].

While this was proposed somewhat tongue-in-cheek, it speaks to trainees’ wishes for clear messaging and shared behavioral standards throughout the institution.

Participants recommended departmental- and system-level coaching, education, and training for GD/SH scenarios to facilitate responding to offenders and reporting to leaders.

I think of when we’re told we should set the example for how parents should deal with their children in the exam room . . . It would be helpful to do . . . scenario training where we’re trained how to support staff or how to address egregious behavior in the exam room [in a way] that is both professional but is not going to drag my visit out for 20 minutes longer.

We found that our department was not spared from SH and GD that has been widely reported in academic medicine. Patient-related harassment and discrimination were reported by virtually all women participants and less frequently reported by men. This is consistent with what is found nationally, although one recent German study reported rates of male harassment which were more similar to female frequencies (n=737, 62% of male physicians compared with 76% of female).22 The frequency of these experiences for women was moving and particularly surprised the male member of our research team. Similarly, our findings elicited a wide range of emotional responses from the male members of the department and prompted the residency administration to take an active role in engaging in interventions.

Barriers to reporting, including lack of trust of the system to respond and concern for embarrassment or damage to the reputation of the reporter, are consistent with previous studies about sexual harassment.23 Fear of retaliation and career harms are real barriers that are exacerbated by hierarchy in medical training, with trainees and junior faculty less likely to report. Educational efforts and institutional policies should explicitly prohibit retaliation and describe processes to protect reporters. To the extent that concern about severe consequences for the harasser is a barrier to reporting, this fear may be mitigated through knowledge that graded, proportional, and restorative processes are used after careful gathering of information.

Lack of clarity regarding what rises to the level of being reportable relates both to the frequency of the experience, making it an expected and regular occurrence, and to the doubt and fear that many victims experience, wondering if they somehow deserved or provoked this treatment. Explicit cultural expectations act as facilitators for reporting, whereas commonly shared behavioral expectations result in less ambiguity about what behavior is unacceptable.

Some barriers to action are specific to patient care contexts, including the concern about how to manage inappropriate behavior from patients with psychiatric illnesses. Viglianti et al suggest an algorithm for managing harassment perpetrated by patients that asks primarily “Do you feel safe?” and can be widely implemented to help clinicians trust their inner sense of safety for responding to these incidents.24

Cultural barriers for reporting and responding to episodes of SH and GD will take time to change. While the first step is to recognize the problem and speak about the frequency of the experience, this alone will not change the underlying culture. We must provide clear guidance to our learners and our faculty about responding to GD/SH, including coaching and scripted rejoinders to common experiences. Faculty and residents can benefit from training and practice to provide and receive feedback about gender bias. Faculty and trainees in the larger context of their institutions need clear guidance about reporting GD/SH in teaching and learning settings, and mentors should be trained on how to assist learners with responding and reporting incidents. Ideally, these interventions will result in making it more common to respond to rather than ignore SH and GD.

Well-intended systems with multiple pathways for reporting can sometimes lead to confusion; therefore, an initial goal for all medical centers and departments should be a clear and simple reporting system. In the setting of multiple other barriers to reporting, confusion about how to report may tip the scales in favor of silence. The most important message may be institutional encouragement to seek help from a trusted person if in doubt. The reporting system must have options to remain anonymous and include feedback to the reporter that the complaint has been received, investigated, and if legally allowable, that consequences have occurred. Due to privacy constraints, a clear understanding of the process following any complaint is particularly important.

Prevention efforts have largely focused on brief mandatory SH prevention modules. Reviews of workplace and college campus interventions found that few of these training programs have a theoretical guiding model25 and there is little data about whether these trainings result in long-term behavioral or cultural change.26 Our department has engaged in a process of designing and implementing a series of interventions, including structured discussion of our results, a clear departmental statement of the unacceptability of SH and GD, a Theater of the Oppressed workshop on bystander response during a day-long faculty and residency retreat, and a faculty development workshop practicing responses to real cases for both personal experience and for witnessed behaviors.

Sexual harassment and gender discrimination occur frequently in clinical medicine, especially with female trainees and junior faculty. The structure of medical training, lack of clarity about what rises to the level of reporting, concerns about jeopardizing patient relationships, and confusion about the reporting process are frequent reasons these experiences go largely unreported. Silence and the lack of accountability for the perpetrators perpetuates these behaviors in academic medicine. The results of our study compel us to promote open discussion about SH and GD, to improve reporting processes and to maximize transparency about consequences for harassers. It is essential to have clear processes for reporting and responding to SH and GD to guide any person considering action. We must capitalize on facilitators of reporting, including the natural inclination of clinicians to protect trainees coming behind them.

Furthermore, departmental leadership must continuously engage in a process of quality improvement regarding clear cultural expectations for respectful behaviors amongst clinicians, staff, and patients. Culture change takes time. It will be essential to study the impact of interventions to identify changes that most effectively reduce the frequency of harassment, facilitate educational efforts, and provide a safer environment to learn and practice medicine.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Funding for this project was provided by the McDaniel-Farley Psychosocial Medicine Faculty Development Award received by Dr Russell in 2018.

The authors thank Kathleen Silver for assistance in preparing and submitting this manuscript.

Presentations: Preliminary data analysis of this material was presented at the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Annual Spring Conference in Toronto, Canada, in April 2019, and in poster form at the North American Primary Care Research Group National Conference in Toronto, Canada in November 2019.

References

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Anti-harassment policy. 2020. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/anti-harassment.html. Published 2020. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- Coe C, Piggott C, Davis A, et al. Leadership pathways in academic family medicine: focus on underrepresented minorities and women. Fam Med. 2020;52(2):104-111. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.545847

- McKinley SK, Wang LJ, Gartland RM, et al; Massachusetts General Hospital Gender Equity Task Force. “Yes, I’m the doctor”: one department’s approach to assessing and addressing gender-based discrimination in the modern medical training era. Acad Med. 2019;94(11):1691-1698. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002845

- Cortina L, Berdahl J. Sexual harassment in organizations: A decade of research in review. In: Barling J, Cooper C, eds. Micro Approaches. London, England: Sage Publications; 2008:469-497. The SAGE Handbook of Organizational Behavior; vol 1. doi:10.4135/9781849200448.n26

- Hayes H. Is time really up for sexual harrassment in the workplace? Companies and law firms respond. American Bar Association. 2019. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/diversity/women/publications/perspectives/2018/december-january/is-time-really-for-sexual-harassment-the-workplace-companies-and-law-firms-respond/. Published January 19, 2019. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- Pololi LH, Brennan RT, Civian JT, Shea S, Brennan-Wydra E, Evans AT; Sexual harassment within academic medicine in the United States. Us, too. Am J Med. 2020;133(2):245-248. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2019.06.031

- Fnais N, Soobiah C, Chen MH, et al. Harassment and discrimination in medical training: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acad Med. 2014;89(5):817-827. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000200

- Girgis C, Khatkhate G, Mangurian C. Patients as perpetrators of physician sexual harassment. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(2):279. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.7974

- Jagsi R, Griffith KA, Jones R, Perumalswami CR, Ubel P, Stewart A. Sexual harassment and discrimination experiences of academic medical faculty. JAMA. 2016;315(19):2120-2121. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.2188

- Bates CK, Jagsi R, Gordon LK, et al. It is time for zero tolerance for sexual harassment in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2018;93(2):163-165. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002050

- Benya F, Widnall S, Johnson P, eds. National Academies of Sciences E, and Medicine, Policy and Global Affairs, Committee on Women in Science, Engineering, and Medicine, Committee on the Impacts of Sexual Harassment in Academia. Job and Health Outcomes of Sexual Harassment and How Women Respond to Sexual Harassment. In: Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; 2018:67-92.

- Hinze SW. ‘Am I being over-sensitive?’ Women’s experience of sexual harassment during medical training. Health (London). 2004;8(1):101-127. doi:10.1177/1363459304038799

- Greenup RA, Pitt SC. Women in academic surgery: A double-edged scalpel. Acad Med. 2020;95(10):1483-1484. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003592

- Vassar L. How medical specialties vary by gender. American Medical Association. Specialty Profiles. https://www.ama-assn.org/residents-students/specialty-profiles/how-medical-specialties-vary-gender. Published February 18, 2015. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- Wadman M. University of Rochester and plaintiffs settle sexual harassment lawsuit for $9.4 million. AAS. Science. 2020. https://www.sciencemag.org/news/2020/03/university-rochester-and-plaintiffs-settle-sexual-harassment-lawsuit-94-million. Published March 27, 2020. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Facts about sexual harassment. US Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. 2020. https://www.eeoc.gov/fact-sheet/facts-about-sexual-harassment. Published 2020. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- Clayton JA, Tannenbaum C. Reporting sex, gender, or both in clinical research? JAMA. 2016;316(18):1863-1864. doi:10.1001/jama.2016.16405

- SAMHSA’s Trauma and Justice Strategic Initiative. SAMHSA’s concept of trauma and guidance for a trauma-informed approach. Washington, DC: US Department of Health and Human Services, Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration, Office of Policy, Planning and Innovation; 2014. https://ncsacw.samhsa.gov/userfiles/files/SAMHSA_Trauma.pdf. Accessed March 3, 2021.

- Borkan J. Crystallization-immersion. In: Crabtree BF, Miller WL, eds. Doing Qualitative Research. Newbury, CA: SAGE Publications, Inc; 1999:179-194.

- Doyle S. Member checking with older women: a framework for negotiating meaning. Health Care Women Int. 2007;28(10):888-908. doi:10.1080/07399330701615325

- Bronfenbrenner U. Toward an experimental ecology of human development. Am Psychol. 1977;32(7):513-531. doi:10.1037/0003-066X.32.7.513

- Jenner S, Djermester P, Prügl J, Kurmeyer C, Oertelt-Prigione S. Prevalence of sexual harassment in academic medicine. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(1):108-111. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2018.4859

- Foster PJ, Fullagar CJ. Why don’t we report sexual harassment? An application of the theory of planned behavior. Basic Appl Soc Psych. 2018;40(3):148-160. doi:10.1080/01973533.2018.1449747

- Viglianti EM, Oliverio AL, Meeks LM. Sexual harassment and abuse: when the patient is the perpetrator. Lancet. 2018;392(10145):368-370. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(18)31502-2

- Anderson LA, Whiston SC. Sexual assault education programs: A meta-analytic examination of their effectiveness. Psychol Women Q. 2005;29(4):374-388. doi:10.1111/j.1471-6402.2005.00237.x

- Medeiros K, Griffith J. # Ustoo: how IO psychologists can extend the conversation on sexual harassment and sexual assault through workplace training. Ind Organ Psychol. 2019;12(1):1-19. doi:10.1017/iop.2018.155

There are no comments for this article.