Abstract: The optimal length of family medicine training has been debated since the specialty’s inception. Currently there are four residency programs in the United States that require 4 years of training for all residents through participation in the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Length of Training Pilot. Financing the additional year of training has been perceived as a barrier to broader dissemination of this educational innovation. Utilizing varied approaches, the family medicine residency programs at Middlesex Health, Greater Lawrence Health Center, Oregon Health and Science University, and MidMichigan Medical Center all demonstrated successful implementation of a required 4-year curricular model. Total resident complement increased in all programs, and the number of residents per class increased in half of the programs. All programs maintained or improved their contribution margins to their sponsoring institutions through additional revenue generation from sources including endowment funding, family medicine center professional fees, institutional collaborations, and Health Resources and Services Administration Teaching Health Center funding. Operating expense per resident remained stable or decreased. These findings demonstrate that extension of training in family medicine to 4 years is financially feasible, and can be funded through a variety of models.

Family medicine residency programs are tasked with training physicians capable of, as the Millis Commission put it in 1966, “highly competent provision of comprehensive and continuing medical services.“1,2 The ability of training programs to deliver on this task has been stressed by the rapid growth of medical knowledge and treatment options. In addition, work hour restrictions have resulted in a reduction in the amount of time residents have available to acquire the necessary knowledge and skills to care for patients in a thorough manner across the life spectrum.3 The optimal length of family medicine training has been debated since the specialty’s inception with recognition that there needed to be flexibility with the residency curriculum and acknowledgement that training could take up to 4 years to complete.4

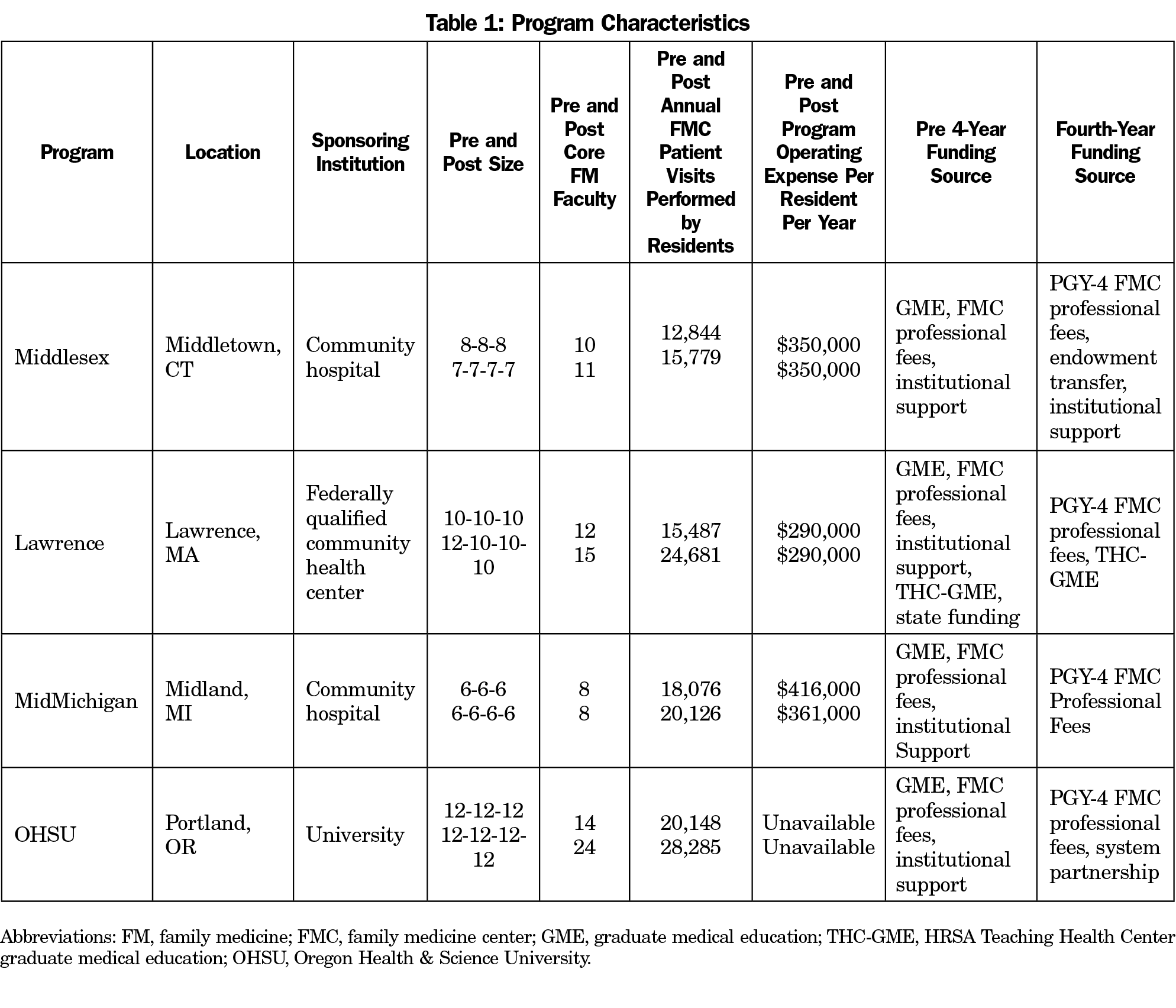

Following the release of the American Academy of Family Physicians’ Future of Family Medicine report in 2004, residency programs were invited by the Preparing the Personal Physician for Practice (P4) project to innovate in order to train modern physicians ready to deliver exceptional, patient-centered care in a rapidly changing health care environment.5,6 Fourteen programs participated, modeling diverse changes in curriculum design, practice location, and training length.7 Middlesex Health Family Medicine Residency Program (FMRP) implemented the nation’s first required 4-year curriculum in 2007 as part of the P4 project.8 The FMRP at Greater Lawrence Health Center, Oregon Health and Science University, and MidMichigan Medical Center began transitioning to a required 4-year model in 2012 as part of the Length of Training Pilot. All programs shared the goals of preparing family physicians with broad skill sets, providing enhanced core curriculum in areas of common deficit such as reproductive health, care of children and practice management, offering in-depth individualized training in areas of concentration, and transforming their family medicine centers (FMCs) into high-functioning patient-centered medical homes (PCMH). All programs implemented additional core rotations, additional training in individualized areas of concentration including advanced degree opportunities, substantial increases in resident outpatient visits, and PCMH-focused practice transformation.9 Other participants in the Length of Training Pilot who offered an optional fourth year of training, only partially implemented a fourth year, or were sponsored by the United States Navy are not described here.

Financing an additional year of training has been recognized as a barrier to implementing a required 4-year training model. As federal graduate medical education (GME) funding has been unchanged for nearly 25 years and direct support beyond 3 years is reduced by 50%, many sponsoring institutions have been hesitant to expand beyond the traditional 3-year model.10 However, as described by Carney et al in this issue of Family Medicine, these programs, at a variety of types of sponsoring institutions, underwent extensive planning processes to fund the fourth year of training. All were financially successful utilizing a variety of approaches. This article describes their experiences and elucidates common themes.

A Primer on Financing an Additional Year of Training

When adding a year of training, a program must fundamentally decide whether to reduce class size to maintain a stable total resident complement (eg, 8-8-8 to 6-6-6-6), or maintain class size and increase total resident complement (eg, 8-8-8 to 8-8-8-8). In the former case there is essentially no additional operating expense, but federal GME revenue may decrease due to the 50% reduction in direct federal GME reimbursement in the PGY-4 year. In the latter, operating expenses will increase, but professional revenue generated by resident FMC visits will also rise as long as there is demand for additional primary care services within the health care market the residency program serves. The degree to which these changes in expenses and revenue offset each other will vary.

If complement expands, additional operating expenses will at a minimum include the salary and benefits of additional residents. Additional faculty may be required to develop curriculum or maintain required FMC precepting ratios, which will add substantial operating expense. If additional space or infrastructure is required, substantial capital and operational expenses may be incurred.

Most programs rely on federal GME support for a substantial portion of their revenue. Since fourth-year residents are beyond the initial residency period, which for family medicine is 3 years, direct graduate medical education (DGME) reimbursement is reduced by 50%.11 Therefore, if a program is below or at cap and maintains its resident complement, it will incur a 12.5% net reduction in total DGME revenue. However, if above cap, the impact will be reduced. Since DGME reimbursement rates vary widely, the impact of a reduction in DGME payments will vary. Further, indirect medical education (IME) payments, which are typically substantially larger than DGME, are not reduced.

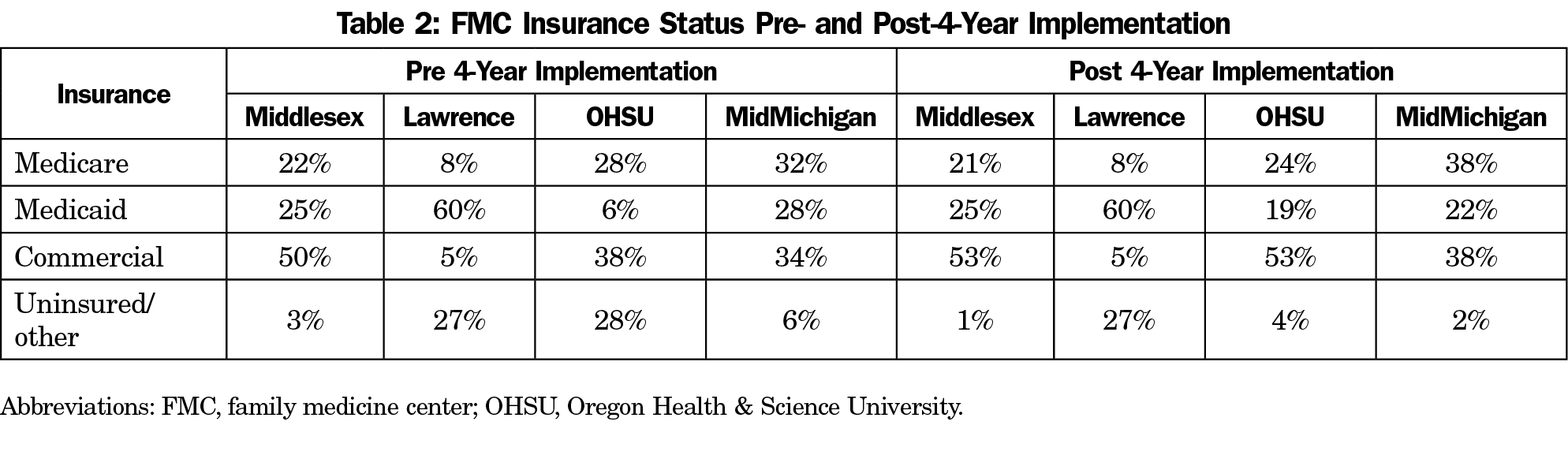

If complement expands, additional resident positions will likely be above cap, and therefore have no impact on DGME revenue. Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) Teaching Health Center, state, grant, or institutional funding can provide additional revenue. Further, residents will reliably generate additional revenue through FMC visit professional fees, which, depending on payor mix, can be substantial.

Total program operating expense to train a resident is a valuable financial benchmark. It was reported in 2016 for traditionally funded programs as an average of $323,000 per resident per year,12 and for HRSA Teaching Health Center-funded programs in 2017, as an average of $245,000 per resident per year.13

Individual Program Experiences

Middlesex Health FMRP

The Middlesex Health FMRP is a community hospital-sponsored, university-affiliated program, accredited in 1973 with three FMCs in urban, suburban, and rural settings in central Connecticut. Beginning in 2007 it initially maintained a stable total resident complement, transitioning from 8-8-8 to 6-6-6-6. The only major additional expense incurred was the one core faculty member to assist with additional curriculum development, which was initially offset by a 2-year funds transfer from a sponsoring institution endowment fund. Since the program was operating above cap it experienced no change in DGME reimbursement.

In 2010, after the transition to 6-6-6-6 was complete, the program began a self-funded expansion to 7-7-7-7 staffing. Salaries and benefits for the additional four residents were more than offset by professional revenue generated by the combination of an average of 900 PGY-4 outpatient visits and practice management initiatives in the FMCs aimed largely at appropriate visit coding. Between 2010 and 2019 average outpatient net revenue per visit increased from $91 to $136, outpatient visit volume rose from 26,800 to 32,600, and net practice revenue rose by $2,000,000 annually. The program maintained a stable contribution margin to its sponsoring institution. Average program operating expense per resident remained stable at $350,000 per resident per year.

Lawrence FMRP

The Lawrence FMRP is sponsored by a federally qualified community health center (FQHC) accredited in 1994 and located in Lawrence, Massachusetts. The residency was originally established and supported by the FQHC largely as a workforce development and retention tool. It facilitated the health center’s expansion and a reduction of its HPSA score from 14 in 2001 to nine in 2014. Founded 15 years prior to the HRSA Teaching Health Center program, program funding was unique with federal GME funding to the partner community hospital passed through to the health center. In 2010 the program expanded from 8-8-8 to 10-10-10 with HRSA Teaching Health Center GME (THC-GME) funding, so that by 2013 the main sources of revenue were traditional GME from the hospital for up to 24 residents, THC-GME for six residents, and resident-generated professional revenue. Faculty patient care revenue was not credited to the residency program. The program traditionally ran a substantial financial deficit.

The addition of a fourth year provided increased patient care revenues that more than offset the additional expenses of the PGY-4 residents. By 2018, the residency was operating with a surplus. Some of this surplus can be credited to additional THC-GME PGY-4 funding. Between 2014 and 2018 average professional revenue per resident increased from $94,000 to $141,500 per resident per year. Average program operating expense per resident remained stable at $290,000 per resident per year.

Throughout development of a fourth year and program expansion, the program was significantly challenged by the uncertainty of THC-GME funding. Between 2013 and 2020 funding was only renewed for 1-2 years at a time, and fluctuated between $85,000 and $150,000 per position. Each academic year, the institution was forced to consider whether to recruit for 10 or eight positions based on the level of perceived funding risk. In 2014 and 2015 only eight residents were recruited. In 2018, the THC program was again threatened with nonrenewal, but financial analysis showed that the higher patient care revenue generation by PGY-3 and PGY-4 residents offset much of the financial risk of potentially unfunded THC-GME positions, and the 10-resident class size was maintained. In 2019, the program was able to expand to 12 residents per class utilizing new state funding for all 4 years of training.

MidMichigan FMRP

The MidMichigan FMRP is a community hospital-sponsored, university-affiliated program, accredited in 1970 and located in central Michigan. In 2012, the program began increasing its resident complement from 6-6-6 to 6-6-6-6. The program’s financing plan was near budget neutral, relying on the six additional residents to both increase empaneled patients by 3,600 and generate additional outpatient professional revenue to offset their salaries. The program’s feature of daily resident office hours facilitated this arrangement. To support the increased resident complement and associated precepting demands, two additional core faculty were recruited. Ultimately, those two faculty offset unexpected faculty departures resulting in no net increase in core faculty size.

In 2016, each member of the first PGY-4 class performed over 1,000 outpatient visits, resulting in an increase of 6,059 outpatient visits and net revenue of just over $1,000,000. Net revenue per visit rose from $158 to $200. Despite multiple subsequent changes including the loss of two faculty with resultant decreases in FMC volume and multiple residents extending their training following leaves with resultant increases in salary expenses, the program has improved its contribution margin to its sponsoring institution. Average program operating expense per resident between 2015 and 2019 decreased from $416,000 to $361,000 per resident per year.

Oregon Health & Science University (OHSU) FMRP

The OHSU FMRP is a university-sponsored program accredited in 1971 and located in Portland, Oregon. Training occurs within multiple hospitals, two community, two rural, and five continuity FMCs, including one FQHC. It began transitioning its resident complement in 2012 from 12-12-12 to 12-12-12-12. Due to timing issues with entry into the Length of Training Pilot, the initial PGY-4 class completed a 3-year residency with the fourth year structured as a clinical fellowship year with independent credentialing and billing. All subsequent classes completed a fully integrated 4-year curriculum.

At the time of the complement expansion, Kaiser Northwest Permanente offered to partner with the program in residency education. It subsidized three residents per year based at the Kaiser FMC (12 residents total) at a rate of $115,000 per resident per year, and made in-kind contributions that included dedicated faculty time and staff support. The association has been a successful one, and the initial 5-year contract has since been renewed. PGY-4 residents averaged 850 visits in the FMCs with over 40% of visits billed at a visit level of four or higher. Financial performance has been viewed as successful by the department.

There is currently significant national interest in extended duration of training in family medicine in response to decreased total training time following implementation of duty hours, increasing care complexity, strong interest in curricular individualization, and a desire to maintain a broad scope of practice. Funding has been identified as a major barrier to broader implementation. This study demonstrates that it is financially feasible to implement a 4-year training model in a variety of settings.

The increase in operational expenses associated with expansion varies based on program structure and the degree of complement expansion. However, in any scenario additional sources of revenue to offset those expenses are necessary. Unfortunately, in most cases federal GME support is fixed. The most common source of additional revenue is professional services provided by fourth-year residents in the outpatient setting. While attractive, it is dependent on a demand for additional visits by the FMC patient population, space for additional patient care hours in the clinic physical plant, and a favorable payor mix. Over the past decade THC-GME funding has provided a new source of revenue for programs based at Community Health Centers. However, it has not proved to be a predictable or reliable funding stream and its future is uncertain. Other potential external sources of revenue include institutional support, state funding, community partnerships, endowments, and grants. Residency programs are in a favorable position to negotiate such support given their substantial indirect financial value to their sponsoring institutions and communities, and ability to enhance recruitment and retention of an in-demand primary care workforce. Given that many residency program FMCs are financially inefficient, innovations in practice management, coding, and insurance contracting can also substantially increase net revenue per visit in all programs, regardless of length of training.

This case report has several limitations. It reports the experiences of only four programs that vary widely in location, sponsorship, structure, financing, and size. This variability allows presentation of only a limited number of high-level financial indicators. We recognize that more granularity of data on revenue and expenses would be of value to other programs, and hope that larger and more detailed studies will be possible in the future.

This study demonstrates that sustainable funding of a fourth year of training in family medicine is achievable in a variety of program models. All programs in this analysis achieved financial stability, maintaining or improving their contribution margins to their sponsoring institutions. Average operational expense per resident in programs able to report it remained stable or decreased and was consistent with nationally reported data. Sources of additional revenue to offset the expense of PGY-4 residents and program expansions included FMC professional fees, THC-GME funding, endowment transfers, and health system partnerships.

References

- The Millis Commission report. GP. 1966;34(6):173-188.

- Willard WR. Rational responses to meeting the challenge of family practice. JAMA. 1967;201(2):108-111. doi:10.1001/jama.1967.03130020054012

- Duane M, Green LA, Dovey S, Lai S, Graham R, Fryer GE. Length and content of family practice residency training. J Am Board Fam Pract. 2002;15(3):201-208.

- Carek PJ, Anim T, Conry C, et al. Residency training in family medicine: a history of innovation and program support. Fam Med. 2017;49(4):275-281.

- Martin JC, Avant RF, Bowman MA, et al; Future of Family Medicine Project Leadership Committee. The Future of Family Medicine: a collaborative project of the family medicine community. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 1):S3-S32. doi:10.1370/afm.130

- Douglass AB, Rosener SE, Stehney MA. Implementation and preliminary outcomes of the nation’s first comprehensive 4-year residency in family medicine. Fam Med. 2011;43(7):510-513.

- Bucholtz JR, Matheny SC, Pugno PA, David A, Bliss EB, Korin EC. Task Force Report 2. Report of the Task Force on Medical Education. Ann Fam Med. 2004;2(suppl 1):s51-s64. doi:10.1370/afm.135

- Carney PA, Eiff MP, Waller E, Jones SM, Green LA. Redesigning Residency Training: Summary Findings From the Preparing the Personal Physician for Practice (P4) Project. Fam Med. 2018;50(7):503-517. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.829131

- Carek PJ. The length of training pilot: does anyone really know what time it takes? Fam Med. 2013;45(3):171-172.

- Committee on the Governance and Financing of Graduate Medical Education; Board on Health Care Services; Institute of Medicine; Eden J, Berwick D, Wilensky G, editors. Graduate Medical Education That Meets the Nation's Health Needs. Washington, DC: National Academies Press; September 30, 2014.

- Congressional Research Service. Federal Support for Graduate Medical Education: An Overview. December 27th, 2018: https://fas.org/sgp/crs/misc/R44376.pdf. Accessed May 24, 2020.

- Pauwels J, Weidner A. The cost of family medicine training: impacts of federal and state funding. Fam Med. 2018;50(2):123-127. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.844856

- Regenstein M, Nocella K, Jewers MM, Mullan F. The cost of resident training in teaching health centers. N Engl J Med. 2016;375(7):612-614. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1607866

There are no comments for this article.