Background and Objectives: Faculty shortages are a significant concern in family medicine education. Many family medicine residency programs need to recruit faculty in the coming years. As a result, family medicine faculty and resident physicians will be interviewing candidates to fill these vacancies. Little is known about the characteristics valued in a family medicine residency faculty candidate.

Methods: Using a cross-sectional survey of family medicine faculty and resident physicians in family medicine residency programs in Kansas, we attempted to define which characteristics are most valued by current faculty members and resident physicians in family medicine residency programs during the faculty hiring process.

Results: Of 187 invited respondents, 93 completed the survey (49.7% response rate). Twenty-five characteristics, grouped into five domains of relationship building, clinical, teaching, research and administrative skills, were rated as either not important, important, or very important. Building and maintaining healthy relationships was the most important characteristic for faculty, residents, males, and females. Administrative characteristics were the lowest ranked domain in our survey.

Discussion: These results provide an important snapshot of the characteristics valued in faculty candidates for family medicine residency programs. Understanding the paradigm used by existing faculty and resident physicians in family medicine residency programs when considering new faculty hires has an important impact on faculty recruitment and faculty development programs.

Department chairs and residency program directors in family medicine have noted faculty shortages are a significant concern for medical education.1 Similar concerns have been described by the Association of Academic Health Centers, the Association of American Medical Colleges, and the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine.1-3

A 2019 study of family medicine residency program directors and department chairs revealed that family medicine departments had an average of 3.9 vacancies in the preceding year.5 Further, departments were able to fill only 66% of vacancies with at least one position remaining open for over 1 year.4 Moreover, Corrice et al reported that 30% of family medicine faculty left positions over a 3-year period.5 Current vacancies, high turnover, and ongoing growth of family medicine residency programs suggest that many programs are or will be recruiting faculty over the next few years.

The factors that lead an individual to apply for an academic position are not well understood. Although values, mentorship, and debt may be part of a complex set of factors that influence physicians, the specific factors that lead to selection of an academic careers are still largely undefined.6-7

Furthermore, once an individual has applied for a faculty position, little is known about what characteristics interviewers may prize in a faculty candidate. We found no studies that examined how family medicine faculty and resident physicians rate the importance of various skills and characteristics when considering hiring a new faculty member.6-7

Multiple studies suggest that gender bias exists in the hiring process across disciplines in science, some suggesting that a male candidate may be preferred even if his qualifications are inferior to a female candidate.8-14 Also, an analysis of 7,326 teaching evaluations revealed that evaluations of males tended to include words such as “big picture,” “run rounds,” “master,” “art,” and “master clinician,” whereas evaluations of females tended to include words such as “empathetic,” “delight,” “warm,” and “attention to detail.”15 While differences exist in how males and females are perceived by learners or during the hiring process, a question remains if male and female interviewers seek out different characteristics in applicants for family medicine residency faculty positions.

This study seeks to describe characteristics that are deemed important in a faculty applicant for a family medicine residency faculty position and to further describe the impact of faculty or resident interviewer status as well as male or female gender on what characteristics are valued. We hypothesized that faculty and residents may differ in the characteristics valued in a faculty member. Similarly, we hypothesized that males and females may value different characteristics. Such differences in preferences could result in hiring decisions that are influenced by the demographic makeup of the interview committee. Understanding what is valued in faculty applicants may aid residency programs in designing an optimal process and metrics for recruitment of faculty.

This cross-sectional survey of all family medicine faculty and resident physicians in the four family medicine residency programs in Kansas—of which three are community based, university affiliated, and one is university based—was conducted from February 2019 through April 2019. The University of Kansas School of Medicine Institutional Review Board approved the study. All family medicine faculty and resident physicians associated with family medicine residency programs in the state of Kansas were invited to participate in an online survey. All potential responders were given a link to the online survey within an email invitation, which was created using SurveyMonkey. Participants were informed that completing the survey would act as consent to participate. All respondents were assured that no data were collected that allowed individuals or specific residency programs to be identified. Nonresponders were emailed up to three times over a 6-week period before the survey data collector was closed.

Using the promotion and tenure guidelines available to faculty at the University of Kansas School of Medicine, we developed 25 characteristics of faculty candidates that represent persons skilled in one of five domains, including administrative, clinical, relationship building, research, and teaching. The survey asked respondents to use a Q-sort methodology to rank the importance of each of the 25 characteristics listed in Tables 2 and 3.16 The specific instructions on the survey were:

You have a vacancy on your current residency faculty and have been asked to recommend which candidate should be hired for the vacancy. Assume the candidates otherwise have the same qualifications, experience and planned scope of practice. Please sort the characteristics into one of the following categories.

- Not important for the candidate to possess this characteristic

- Important for the candidate to possess this characteristic

- Very important for the candidate to possess this characteristic

We also collected demographic data about the respondent.

We conducted data analysis using SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 25.0 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp). We analyzed the demographic characteristics of survey respondents using descriptive statistics. We evaluated responses by role in program, comparing faculty and resident responses as well as gender, comparing male and female responses. Differences in the proportion of each subgroup that indicated the characteristic was very important were analyzed using t tests.

A total of 187 individuals were invited to participate in the online survey. Of these, one person opted out and 101 individuals opened the email. Of the individuals who opened the email, 93 completed the survey, for a participation rate of 92.1% and a response rate of 49.7% of all invited.

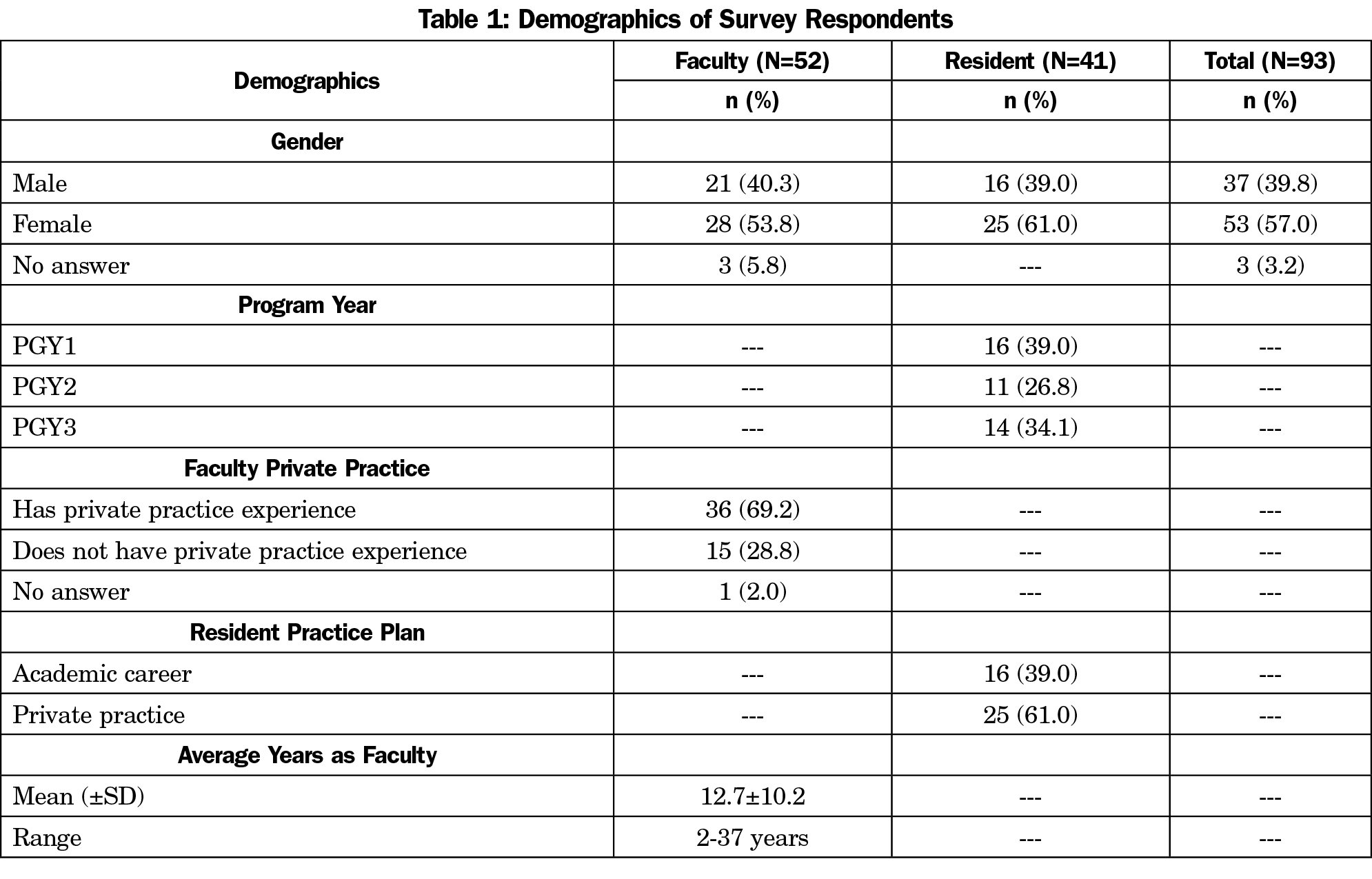

Of the 187 individuals invited to participate, 93 were faculty and 94 were residents. Fifty-two of the 93 faculty completed the survey (55.9%), and 41 of the 94 resident physicians completed the survey (43.6%). Thirty seven respondents identified as male (39.8%), 53 identified as female (56.9%), and 3 (3.2%) declined to identify a specific gender. Table 1 describes the demographic attributes of the respondents.

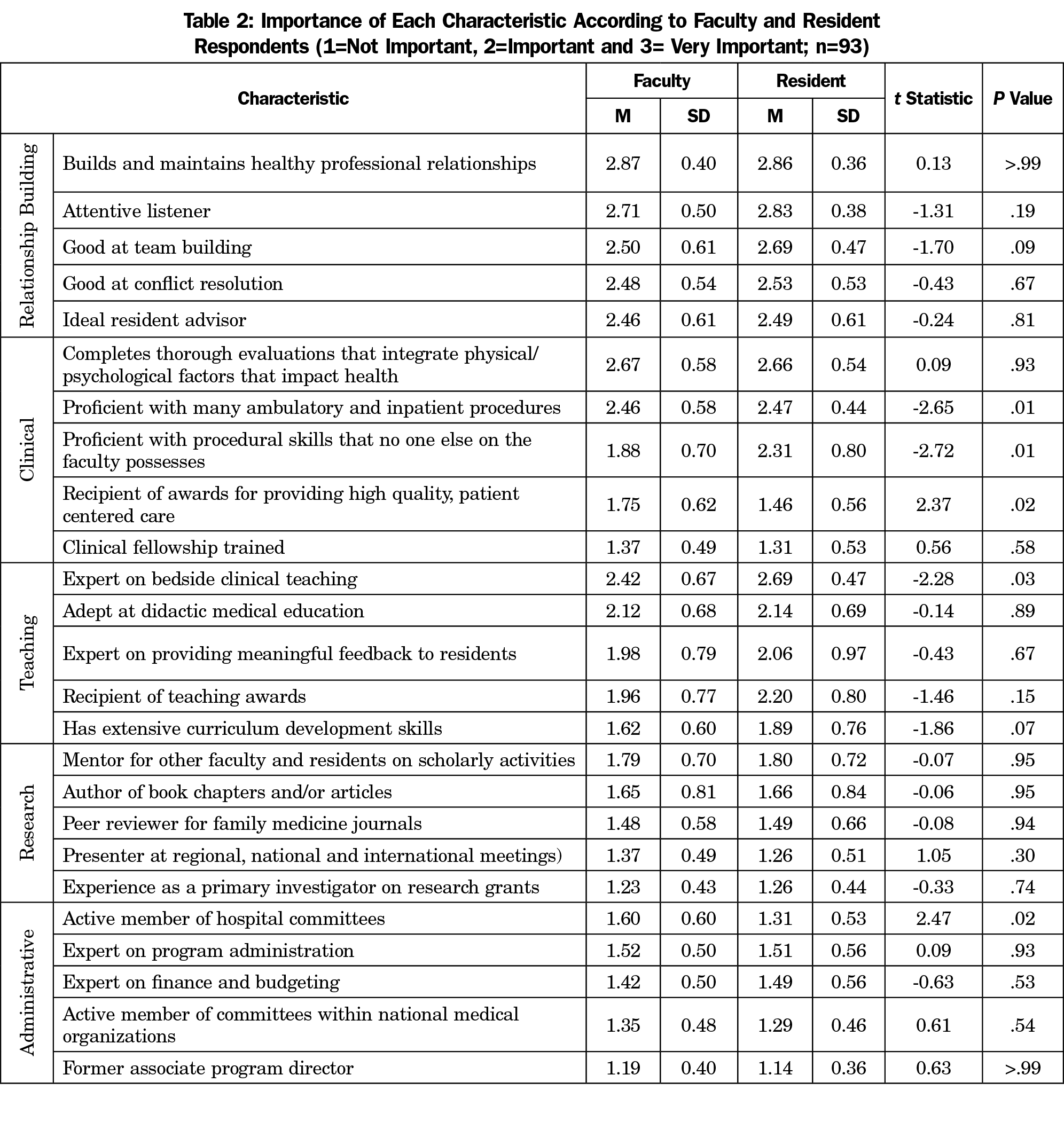

Each respondent evaluated 25 characteristics in a hypothetical faculty member and classified each as not important, important, or very important. Building and maintaining healthy relationships was highly valued by both faculty and resident physicians. Building and maintaining healthy relationships was noted to have a mean of 2.87 for faculty and 2.86 for residents, which was the highest of any characteristic. Similarly, administrative characteristics had the lowest means for faculty and residents with no administrative characteristic having a mean of greater than 1.60 for faculty and 1.51 for residents.

Table 2 describes each characteristic as well as the mean and standard deviation for faculty and resident groups of respondents who classified characteristics as not important (1), important (2), or very important (3). Residents rated “proficient with many ambulatory and inpatient procedural skills,” “proficient with procedural skills that no one else on the faculty possesses,” and “expert on bedside clinical teaching” as statistically significantly more important that did faculty. Faculty rated “recipient of awards for providing high quality,” “patient-centered care” and “active member of hospital committees” as statistically significantly more important than did residents.

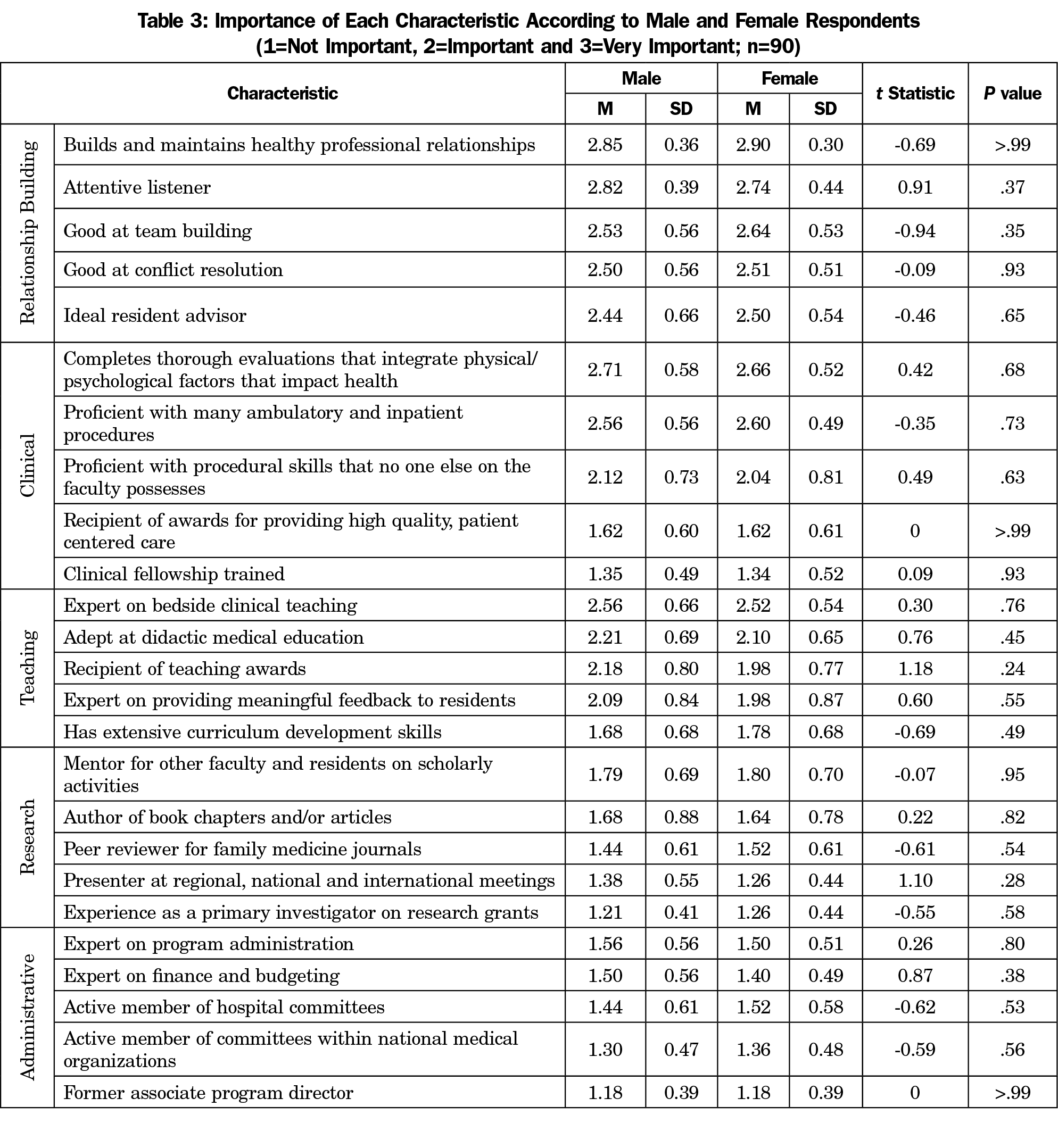

Table 3 describes each characteristic as well as the mean and standard deviation for male and female groups of respondents who classified characteristics as not important (1), important (2), or very important (3). There were no statistically significant differences in the importance rating of each characteristic when comparing male and female respondents.

Family physicians prize relationships with patients and colleagues. Perhaps not surprisingly, strong relationship-building characteristics are among the highest valued traits in a candidate for a faculty position. When all 25 characteristics were ranked by mean score, all five relationship characteristics were within the top eight items on the list. Conversely, all five administrative characteristics were among the lowest eight items on the list.

Although this study provides information about which characteristics are valued by faculty and resident physicians, it does not provide information about why the respondents selected the characteristics that they did. From our experience, we suspect that many factors may contribute to our findings. Perhaps administrative characteristics are perceived as easier to teach through targeted faculty development, making the need to find a candidate who already possess such skills less important. Faculty and residents may believe that administrative skills can be taught whereas relationship building skills may be more difficult to develop. Similarly, faculty and residents may consider administrative tasks to be less critical for the average faculty member. Also, the number of administrative tasks required of a successful faculty member may be underrecognized and thus not sought after in a candidate. It should be noted that our survey asked about characteristics valued in a faculty candidate. Responses might change and administrative prowess may be more highly valued in an applicant for an associate program director or medical director role.

Faculty and resident respondents placed statistically significantly different importance on five of the 25 characteristics. Residents placed more importance on faculty with broad and unique procedural skills as well as expertise in bedside clinical teaching. Faculty, meanwhile, placed more importance on a faculty candidate having been recognized with awards for high-quality care and having served on hospital committees.

In future studies we hope to examine why a difference between faculty and residents exists as it relates to the importance of various characteristics. We suspect the increased importance of procedural skills and clinical teaching may suggest that residents value proficiency in the clinical arena as a marker of a successful faculty member as opposed to skills in didactic teaching, administrative or research work. Studies of residents considering academic careers have suggested that residents may avoid academic careers because of lack of clinical readiness or ability to be successful in multiple domains.17 A lack of a unique or broad procedural skill set or lack of confidence in bedside clinical skills may be seen as lack of readiness by residents. Residents may believe that without first being a strong clinician, a faculty member will not be successful. Faculty, meanwhile, may place less importance on these skills, recognizing that while clinical skills are important, bedside clinical proficiency and broad procedural skills alone will not translate into a successful faculty member. Furthermore, faculty may place less emphasis on unique procedural skills as practical concerns such as credentialing, cross-coverage issues, or obtaining needed equipment and supplies may overshadow the value of having a single faculty member who performs a given procedure.

Faculty placed more value on active participation on hospital committees than did residents. While all of the administrative characteristics were not highly valued by either faculty or residents, participation on hospital committees can be important for the ongoing success of a family medicine residency program. Faculty may be more aware of the political relationships that are important for the health and success of a family medicine residency program and thus may value input and participation on hospital committees more highly than the residents do.

Males and Females

Interestingly, we found no statistically significant differences in the importance ratings of male and female respondents regarding any of the 25 characteristics of a faculty candidate. Other studies have demonstrated that while female candidates may be held to strict criteria during the hiring process, male candidates may be assumed to be able to acquire skills required that they do not possess.18 While our study reveals that both males and females highly value a candidate being able to build and maintain healthy professional relationships, we did not assess what criteria would be used to determine that a candidate possessed that skill or if male and female candidates would be evaluated differently.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. The survey was created using domains and characteristics typically evaluated during a promotion and tenure process. While this provided a useful framework, there may be characteristics critically important in faculty candidates that were not evaluated, as they did not fit into this framework. We invited only family medicine residents and faculty within the state of Kansas to participate, and the faculty characteristics valued by these individuals may not be the same as those valued in other institutions or geographic locations. We collected minimal demographic data and other attributes about respondents may have influenced our results. Further, the current resident and faculty makeup of a program may influence the responses that a faculty or resident provided on the survey. For example, if a faculty member with a specific clinical characteristic set was needed in the program at the time of the survey, the respondent may have ranked clinical characteristics higher than he or she would have otherwise done. Although we asked respondents to rank characteristics that would be important in a faculty candidate, we did not define a hypothetical role that the faculty member was filling. Responses may have varied if a job description had been provided or roles defined that the hypothetical faculty candidate would need to fill. Nonetheless, this data provides an important snapshot of the characteristics valued in faculty candidates for family medicine residency programs.

Understanding the paradigm used by existing faculty and resident physicians in family medicine residency programs when considering hiring new faculty has important impacts on faculty recruitment and faculty development programs. Our study suggests that faculty, residents, males, and females place emphasis on relationship building, and clinical and teaching skills over research or administrative prowess. Also, residents place more importance than faculty on procedural and bedside teaching skills when evaluating a faculty candidate. Faculty development and resident academic career preparation programs may need to focus on building research and administrative skills if the hiring process tends to select candidates with alternative strengths.

Moreover, knowing that importance is placed on specific skills may help programs to design an interview and hiring process that helps clarify those skills in each applicant. If a faculty is required to have skills in areas that are not typically rated as important, such as expertise in finance and budgeting, perhaps a dedicated investigation of the applicant’s abilities in this area would be important, as interviewer questions may otherwise not focus on this skill.

As more and more family medicine residency programs face the need to recruit and hire faculty, an enhanced understanding of the values of current faculty and resident physicians may provide important information to aid the process. Future studies will aim to survey more residency programs to determine if our data is limited to Kansas or is more generalizable. Undertaking studies designed to assess how interviewers evaluate potential candidates for important characteristics will be important to fully develop hiring interventions.

References

- Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. STFM launches initiative in response to faculty shortage. Ann Fam Med. 2015;13(3):290-291. doi:10.1370/afm.1800

- Association of Academic Health Centers. Academic Health Center CEOs Say Faculty Shortages Major Problem. http://www.aahcdc.org/Portals/41/Series/Issue-Briefs/Faculty_Shortages_Major_Problem.pdf. Published 2007. Accessed June 4, 2020

- Association of American Medical Colleges. Results of the 2016 Medical School Enrollment Survey. https://members.aamc.org/iweb/upload/Results%20of%20the%202016%20Medical%20School%20Enrollment%20Survey.pdf. Published May 2017. Accessed June 4, 2020

- Everard KM, Zoberi K, Jacobs C. Factors associated with successfully filling faculty vacancies in family medicine. Fam Med. 2019;51(6):489-492. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.313365

- Corrice A, Fox S, Sarah B. Retention of full-time clinical MD faculty at US medical schools. AAMC Analysis in Brief. 2011;11(2):1-2.

- Borges NJ, Navarro AM, Grover A, Hoban JD. How, when, and why do physicians choose careers in academic medicine? A literature review. Acad Med. 2010;85(4):680-686. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181d29cb9

- Weaver SP. Family medicine academic workforce: a national study of faculty numbers and types. Fam Med. 2015;47(2):131-133.

- Moss-Racusin CA, Dovidio JF, Brescoll VL, Graham MJ, Handelsman J. Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2012;109(41):16474-16479. doi:10.1073/pnas.1211286109

- Steinpreis R, Anders KA, Ritzke D. The impact of gender on the review of the curricula vitae of job applicants and tenure candidates: a national empirical study. Sex Roles. 1999;41(7/8):509-528. doi:10.1023/A:1018839203698

- Knobloch-Westerwick S, Glynn CJ, Huge M. The Matilda effect in science communication: an experiment on gender bias in publication quality perceptions and collaboration interest. Sci Commun. 2013;35(5):603-625. doi:10.1177/1075547012472684

- Reuben E, Sapienza P, Zingales L. How stereotypes impair women’s careers in science. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(12):4403-4408. doi:10.1073/pnas.1314788111

- Castilla EJ, Benard S. The paradox of meritocracy in organizations. Adm Sci Q. 2010;55(4):543-676. doi:10.2189/asqu.2010.55.4.543

- Quadlin N. The mark of a woman’s record: gender and academic performance in hiring. Am Sociol Rev. 2018;83(2):331-360. doi:10.1177/0003122418762291

- Roper RL. Does gender bias still affect women in science? Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2019;83(3):e00018-e00019. doi:10.1128/MMBR.00018-19

- Janae K Heath, Gary E Weissman, Caitlin B Clancy et al. Assessment of gender-based linguistic differences in physician trainee evaluations of medical faculty using automated text mining JAMA Netw Open. 2019 May 3;2(5):e193520.

- van Exel J, de Graaf G. Q methodology: a sneak preview. from http://qmethod.org/articles/vanExel.pdf. Published 2005. Accessed October 1, 2018

- Lin S, Nguyen C, Walters E, Gordon P. Residents’ perspectives on careers in academic medicine: obstacles and opportunities. Fam Med. 2018;50(3):204-211. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.306625

- Rivera LA. When two bodies are (not) a problem: gender and relationship status discrimination in academic hiring. Am Sociol Rev. 2017;82(6):1111-1138. doi:10.1177/0003122417739294

There are no comments for this article.