Background and Objectives: Increasing the diversity of family medicine residency programs includes matriculating residents with disabilities. Accrediting agencies and associations provide mandates and recommendations to assist programs with building inclusive policies and practices. The purpose of this study was (1) to assess programs’ compliance with Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) mandates and alignment with Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) best practices; (2) to understand perceptions of sources of accommodation funding; and (3) to document family medicine chairs’ primary source of disability-related information.

Methods: Data were collected as part of the 2019 Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance Chairs’ Survey. Respondents answered questions about disability policy, disability disclosure structure, source of accommodation funding, and source of information regarding disability.

Results: Half (56%) of responding chairs reported maintaining a disability policy in alignment with ACGME mandates, while half (52%) maintain a disability disclosure structure in opposition to AAMC recommendations. Funding sources for accommodation were reported as unknown (32.9%), the hospital system (27.1%), or the departmental budget (24.3%). Chairs listed human resources (50.7%) or diversity, equity, and inclusion offices (23.9%) as the main sources of disability guidance.

Conclusions: The number of students with disabilities in medical education is growing, increasing the likelihood that family medicine residency programs will select and train residents with disabilities. Results from this study suggest an urgent need to review disability policy and processes within departments to ensure alignment with current guidance on disability inclusion. Department chairs, as institutional leaders, are well positioned to lead this change.

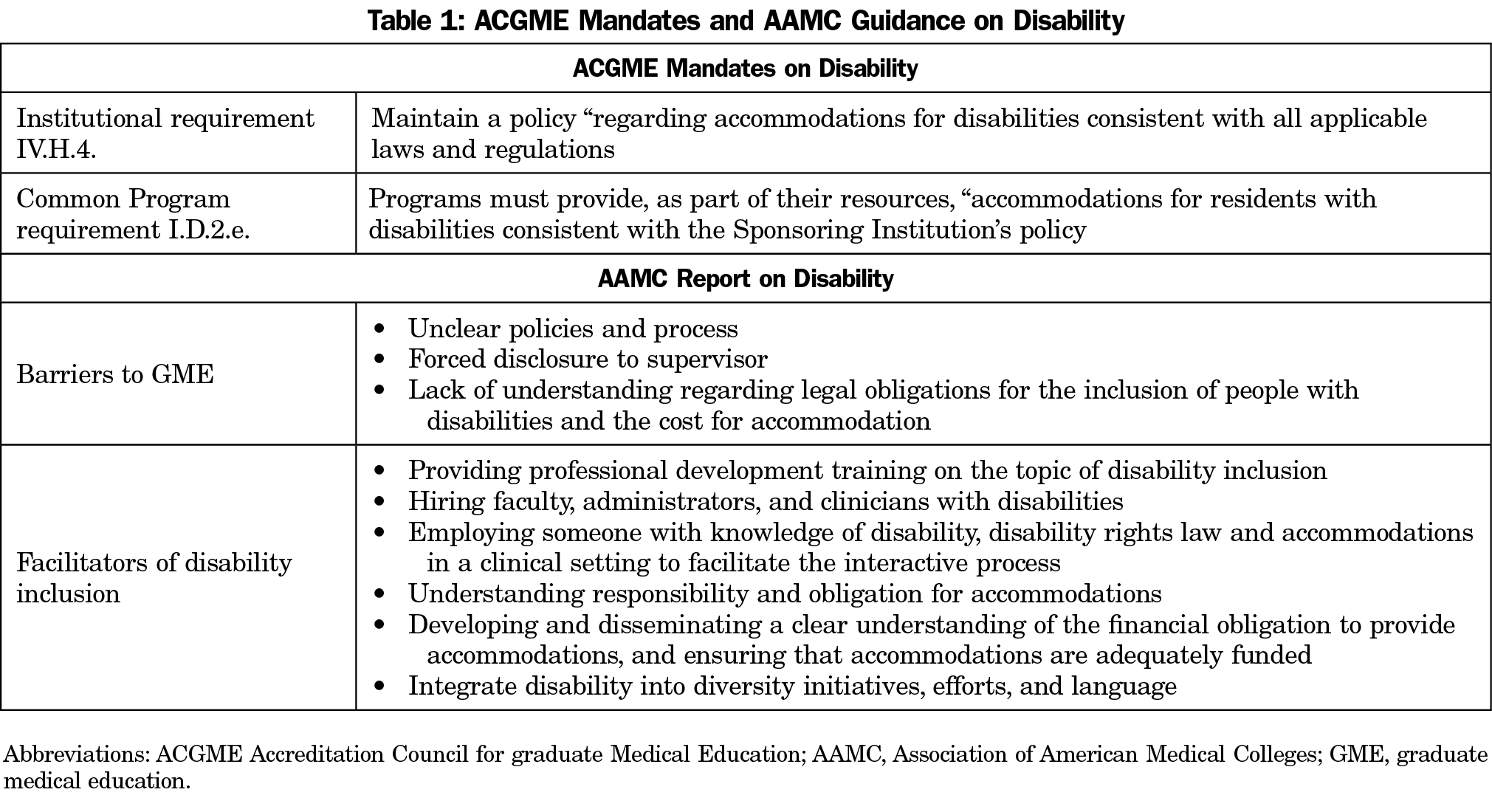

Disability is espoused as a critical part of diversity in medical education. Indeed, as the second largest specialty in the United States, family medicine residency programs will undoubtedly train learners with disabilities, adding to the diversity of our physician workforce. Given this importance, accrediting agencies and associations maintain requirements and offer best practices for improving workforce diversity efforts that include disability.1-9 For example, in 2018, the Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) report on disability identified barriers to the inclusion of residents with disabilities in graduate medical education (GME) and highlighted facilitators of access, including a list of best practices for disability inclusion.4 Simultaneously, the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) introduced new institutional and program requirements related to residents with disabilities including maintaining institutional policies on disability,7 and programmatic requirements to accommodate residents with disability that follow relevant laws and regulations.8 In addition to disability-specific requirements, the ACGME added a set of Common Program Requirements that directly impact diversity and inclusion including:

that the program in partnership with its sponsoring institution must engage in practices that focus on mission-driven, ongoing, systematic recruitment and retention of a diverse and inclusive workforce of residents...9

Efforts to increase diversity suggest that institutional mission statements must align with program efforts and messaging (Table 1).4, 7-8

A recent study suggests that the majority of GME sponsored institutions neither fully comply with requirements, nor align with current recommendations,10 while a similarly-focused commentary offered best practice for inclusive policies in GME.5 As the number of medical students with disabilities grows,11 the disconnect between the potential applicants for residency and residency preparedness may serve as a barrier to the stated goals of increasing diversity in GME.

To our knowledge, no study exists that examines family medicine training programs disability-related policies or practices. In this study our aim was to (1) assess programs’ compliance with ACGME mandates and alignment with AAMC recommendations, (2) identify main sources of accommodations funding, and (3) document chairs’ primary source of information regarding disability-related guidance.

The disability questions were part of a larger omnibus survey conducted by the 2019 Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA).12 The CERA survey was emailed to 200 department chairs of family medicine using SurveyMonkey. One email bounced back, and six opted out, resulting in a sample of 193 family medicine department chairs. The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved the study.

Survey Questions

Family medicine department chaires answered questions about themselves, their medical schools, disability policy, funding structures for accommodations, reporting structure for disclosing disability and their preferred sources for further guidance on disability inclusion.

Analysis

Descriptive statistics summarized the demographic questions and all of the residency program and disability practices questions. We used IBM SPSS Statistics Version 26 for the data analysis for this study.

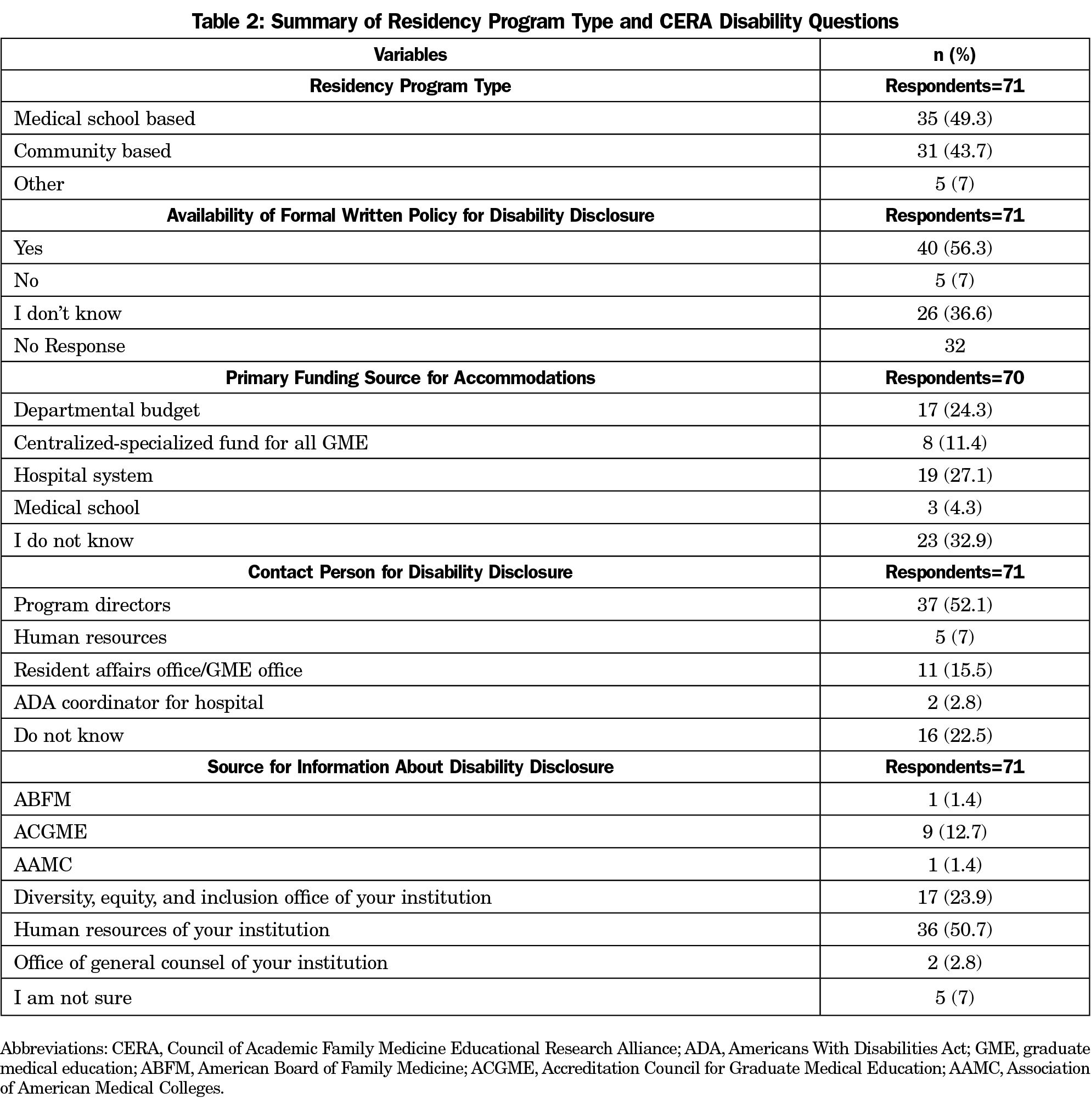

One hundred-five of 193 (54.4%) family medicine department chairs responded to the CERA survey. Descriptive statistics for study variables are summarized in Table 2. Of the 71 department chairs who responded to questions about policy, primary contact for disability disclosure, and sources of guidance regarding disability inclusion, 40 (56.3%) affirmed they maintain a formal written policy for disability disclosure; 37 (52.1%) listed the residency program director as the primary contact for disability disclosure. Most chairs listed human resources (50.7%) or diversity, equity, and inclusion offices (23.9%) as their main source of disability information and guidance.

Seventy chairs responded to the question about accommodation funding; 23 (32.9%) did not know their institutions’ primary funding source for accommodations; 19 (27.1%) listed the hospital system, while 17 (24.3%) listed the departmental budget.

While associations and accreditors are working to facilitate disability inclusion, our findings suggest a disconnect between national guidance and the practices in family medicine training programs. When asked where department chairs would seek guidance on disability-related issues, most listed campus-based offices rather than national associations and accreditation bodies, potentially out of need for local legal precedence.

Our results suggest that while half of family medicine programs align with accreditation mandates for maintaining a disability policy, a third were unable to confirm whether they were in compliance. Approximately one-quarter of chairs were unable to identify the funding structure for accommodations in their department. When asked about the structure for disability disclosure, over half of the department chairs reported a structure in opposition to AAMC guidance, failing to recognize the potential for conflict of interest in reporting to a direct supervisor.

Our findings highlight the urgent need for the review of disability policy and process within departments of family medicine. Chairs, while fiscally constrained, must align practices with educational mandates or efforts towards diversity goals will go unrealized. In addition, the potential conflicts of interest related to program director’s role in the management of accommodations requires further attention/discussion. The need for professional development on the topic of disability inclusion for chairs and their departments is further evidenced by a detailed examination of the barriers reported.

These findings add to our understanding of policy compliance and practices for disability inclusion in family medicine. As the number of students with disabilities in medical education grows,11 it is likely that family medicine residencies will select and train residents with disabilities.

Residency program efforts to meet diversity goals will require aligning organizational and institutional mission statements with program efforts and messaging and comport with current guidance.13 Programs that neglect these efforts, may unintentionally disincentivize disability disclosure, fail to meet accreditation requirements, and create structural barriers for resident training.

Programs might reflect on their internal policies to ensure their practices comport with stakeholder mandates and national recommendations. Family medicine chairs as institutional and departmental leaders are well placed to lead/support this change.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: This project was supported by the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) of the US Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) as part of an award totaling $3,791,026 with 0% financed with nongovernmental sources.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this publication are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily represent the official views of, nor an endorsement, by HRSA, HHS, or the US Government. For more information, please visit HRSA.gov.

References

- Nivet MA. A diversity 3.0 update: are we moving the needle enough? Acad Med. 2015;90(12):1591-1593. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000950

- Nivet MA, Castillo-Page L, Schoolcraft Conrad S. A diversity and inclusion framework for medical education. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):1031. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001120

- Meeks LM, Herzer K, Jain NR. Removing barriers and facilitating access: increasing the number of physicians with disabilities. Acad Med. 2018;93(4):540-543. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002112

- Meeks L, Jain NR. Accessibility, inclusion, and action in medical education: lived experiences of learners and physicians with disabilities. Washington, DC: Assocation of American Medical Colleges; 2018.

- Meeks LM, Jain NR, Moreland C, Taylor N, Brookman JC, Fitzsimons M. Realizing a diverse and inclusive workforce: equal access for residents with disabilities. J Grad Med Educ. 2019;11(5):498-503. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-19-00286.1

- Council on Medical Education of the American Medical Association. A Study to Evaluate Barriers to Medical Education for Trainees with Disabilities. CME Report 4-A-20. Personal communication with American Medical Association; June 7, 2020.

- 7. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. Institutional Requirements 8 IV.H.4. Accommodation for Disabilities: The Sponsoring Institution must have a policy, not necessarily GME-specific, regarding accommodations for disabilities consistent with all applicable laws and regulations. Chicago: ACGME; 2018.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common Program Requirements I.D.2.e. accommodations for residents with disabilities consistent with the Sponsoring Institution’s policy. Chicago: ACGME; 2018.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. ACGME Common Program Requirements (Residency). Chicago: ACGME; June 10, 2018 [updated 2019].

- Meeks LM, Taylor N, Case B, et al. The unexamined diversity: disability policies at US training programs. J Grad Med Educ. 2020. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-19-00940.1

- Meeks LM, Case B, Herzer K, Plegue M, Swenor BK. Change in prevalence of disabilities and accommodation practices among US medical schools, 2016 vs 2019. JAMA. 2019;322(20):2022-2024. doi:10.1001/jama.2019.15372

- Mainous AG III, Seehusen D, Shokar N. CAFM Educational Research Alliance (CERA) 2011 Residency director survey: background, methods, and respondent characteristics. Fam Med. 2012;44(10):691-693.

- Taylor T, Milem J, Coleman A. Bridging the research to practice gap: achieving mission-driven diversity and inclusion goals. New York: College Boards; 2016.

There are no comments for this article.