Background and Objectives: Despite the growing rate of deaths caused by firearms, it is not clear what role physicians should play in counseling patients about firearm safety. This study aims to delineate the perceptions and experiences of family physicians regarding firearm safety counseling.

Methods: Data were gathered as part of the 2020 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine practicing physicians. Participants were practicing physicians and members of one of four major academic family medicine organizations comprising CERA. The survey was delivered to a sample of 3,665 family physicians between January 15, 2020, and March 2, 2020. This was a mixed-methods epidemiological study that analyzed quantitative and qualitative survey data. We calculated a χ2 test of independence to examine interactions between demographic characteristics and beliefs and perceptions about firearm safety counseling.

Results: The overall response rate for the survey was 32.52%, with 92.7% answering questions in the firearm safety set; 93.7% of study participants viewed firearm safety as a public health issue and 95.3% felt family physicians should have the right to counsel patients on firearm safety. Family physicians who had received formal training on firearm safety counseling were significantly more likely to indicate a higher level of comfort with asking their patients about firearms (P<.0001).

Conclusions: Firearm safety is an important public health issue and family physicians would benefit from receiving formal training on firearm safety counseling early in their training. More education is needed around physician-initiated firearm safety counseling.

The annual national death rate from firearms in the United States grew from 10.3 deaths per 100,000 total population in 2005 to 12.0 in 2017.1 Based on these alarming statistics, the issue of physician-initiated counseling for patients on firearm safety has been raised in many different health care and policy forums.2-4 Specifically, the American Academy of Family Physicians’ policy statement on gun violence purports that this is a national public health crisis and recommends screening and educating patients.5 Other literature also points toward a compelling need for education among primary care providers when it comes to firearm safety counseling.3-9 However, it is not clear what educational resources are recommended or how physicians should counsel their patients on firearm safety. One study of pediatric residents identified barriers to firearm safety counseling as residents being unfamiliar with what information to provide about safe storage devices, which led to feelings of discomfort and a lack of confidence in counseling patients.6 Another study of pediatric and other primary care providers in a large urban area found that there was a significant discrepancy in physicians’ perceptions about the need to counsel patients on firearm safety and their actual behavior when it came to counseling their patients.9 It was also found that pediatricians were more likely than family physicians to provide firearm safety counseling to patients when they knew that there were children in the home where firearms exist.10 The issue of gun violence has become so prominent that providers from non-primary care specialties have joined in on the discussion and many are calling for more physician-initiated discussion around this issue.7,8 Moreover, a policy paper published by the American Medical Association agreed that physicians should engage in discussions about gun violence.11

Despite the growing rate of deaths caused by firearms in the United States and the compelling need for the role of health care providers in providing firearm safety counseling, it is not clear how family physicians view their role in this regard, what training they have received, or what experiences they have had when it comes to this needed practice. This national survey study aims to better understand the perceptions and experiences of family physicians regarding firearm safety counseling.

Data Collection

Data were gathered and analyzed as part of the 2020 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of practicing family physicians. CAFM is a joint initiative of four major academic family medicine organizations, including Society of Teachers of Family Medicine, North American Primary Care Research Group, Association of Departments of Family Medicine, and Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors. CAFM members were invited to propose survey questions for inclusion in the CERA survey for general membership. Approved projects were assigned a CERA Research Mentor to help refine questions. The final draft of survey questions was then modified following pilot testing. The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved the study in January 2020.

Participants

Participants were included if they were active members of the major academic family medicine organizations that comprise CERA. As this was a survey for the general membership, program directors, clerkship directors, and department chairs were then excluded. Additionally, the survey contained qualifying questions to ensure that only practicing physicians were surveyed. Invitations to participate in the study included a personalized greeting and a letter signed by the presidents of each of the four sponsoring organizations with a link to the survey, which was conducted through the online program SurveyMonkey. Nonrespondents received five requests, with the final request sent at 2 days before closing the survey, to complete the survey via SurveyMonkey. The survey was distributed to 3,791 candidates. Of these, 10 were returned as undeliverable email addresses and nine were excluded who had previously opted out of receiving surveys from SurveyMonkey. Additionally, 116 respondents did not meet the qualifying questions and were excluded from further survey questions. The survey was delivered to a final sample of 3,665 family physicians (3,541 US and 124 Canadian) between January 15, 2020, and March 2, 2020.

Statistical Analysis

This is a mixed-methods epidemiological study that analyzed quantitative and qualitative survey data. We performed descriptive statistics for demographic data as well as categorical variables using Microsoft Excel version 16.35. We calculated a χ2 test of independence to examine relationships between categorical variables as well as demographic data. We set significance level at .05; we analyzed data using SAS 9.4 statistical software (SAS Institute, Cary, NC). We coded qualitative data in the form of open-ended responses to survey questions for themes and sorted them into categories to draw out patterns from family physicians’ beliefs, perceptions, and experiences about firearm safety counseling.

Patient Characteristics

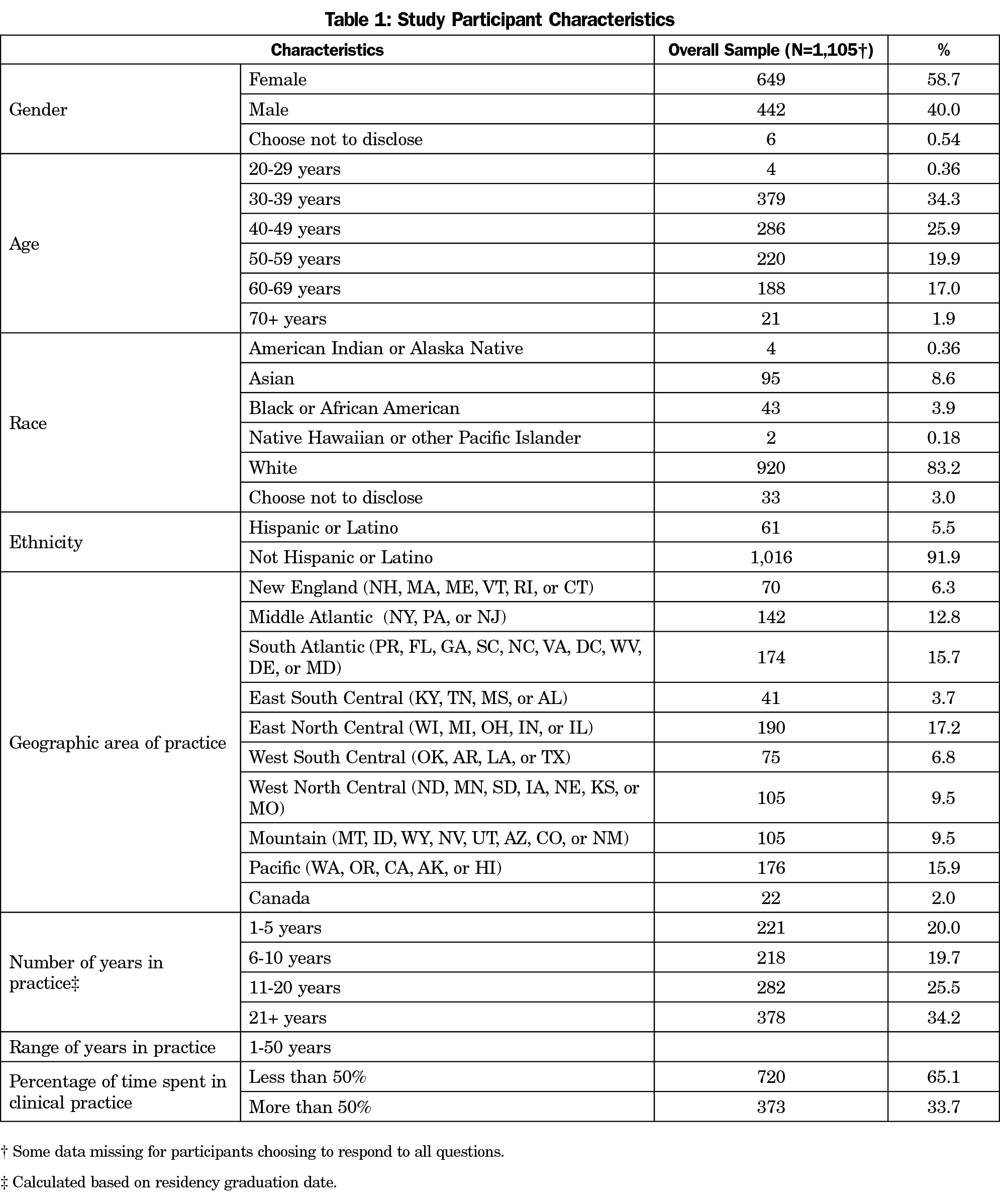

The overall response rate for the survey was 32.52% (1,192/3,665); 92.7% of all respondents answered questions in the set about firearm safety. All respondents were practicing clinicians providing clinical care on a regular basis and all held either an MD or DO degree. Among the respondents of the firearm safety question set, 58.7% were female, 83.2% identified as White, and the majority were younger than 50 years old. See Table 1 for study participant characteristics.

Perceptions and Experiences of Family Physicians Regarding Firearm Safety Counseling

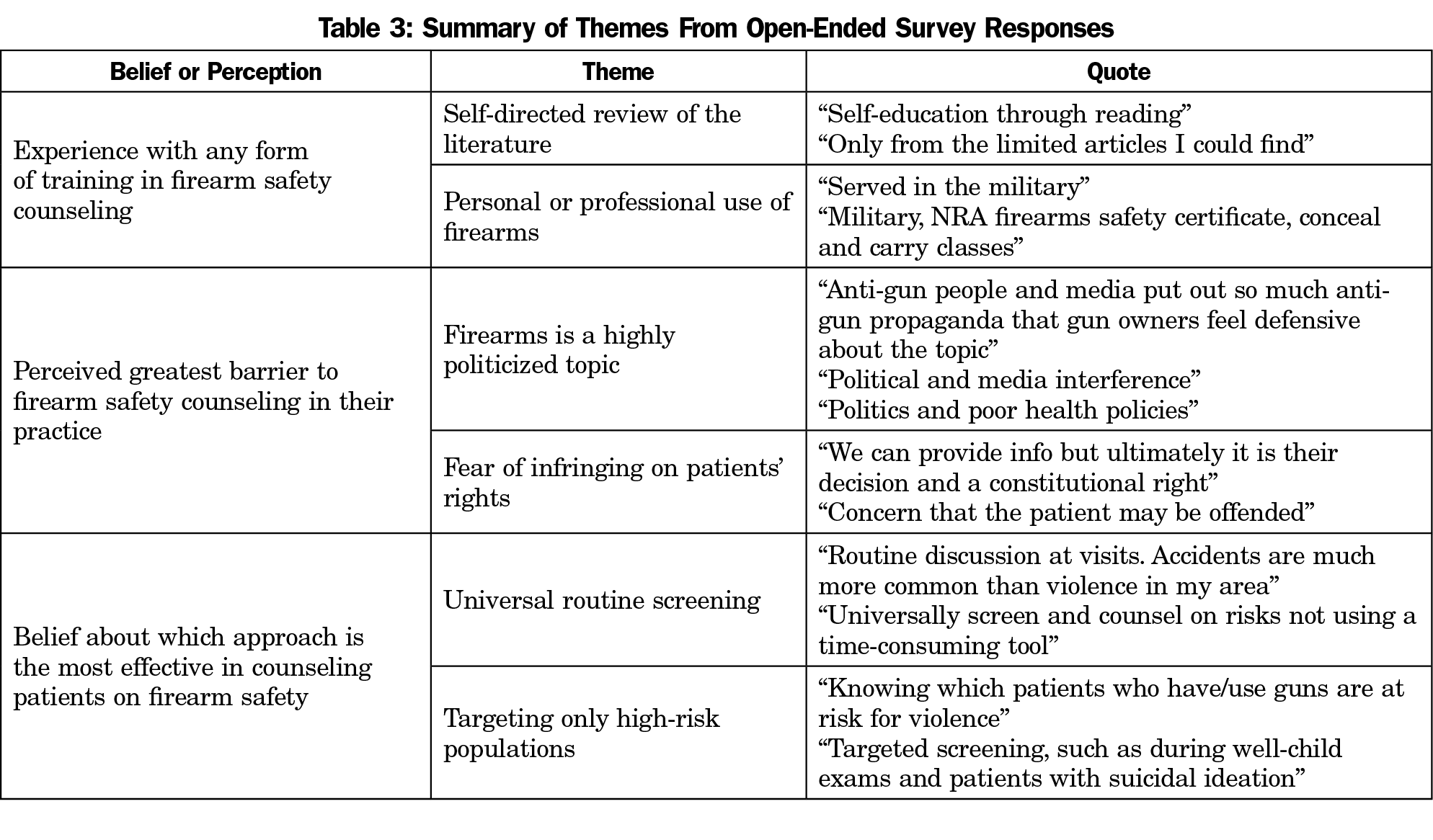

When asked if they thought firearm safety was a public health issue, 93.7% answered yes; 95.3% of participants also felt that family physicians have the right to counsel patients on firearm safety; 91.9% have provided counseling regarding firearm safety to their patients at some point in their clinical career; 53.5% had reportedly received some form of training on firearm safety, and the training they received ranged from education as a medical student to organizational sponsored activities as a practicing physician (Table 2). Other types of training were self-directed and included reading literature from a variety of courses (eg, AAFP website, journal articles) use of firearms (eg, military service, “I am also a police officer,” conceal and carry classes; Table 3).

Survey questions also asked respondents to rate their level of comfort around firearms; 55.9% indicated that they were personally either very uncomfortable or uncomfortable around firearms; 82.3% rated their level of comfort with asking their patients about firearm as either very comfortable or comfortable. However, despite the majority reporting that they were comfortable asking their patients about firearms, 67.9% strongly disagreed or disagreed with the statement, “I am knowledgeable about discussing safe storage devices for firearms with my patients.” Further, only 25% of respondents felt comfortable discussing firearm removal from the home with their patients.

The main barrier to firearm safety counseling identified in this study was time constraints, which was reported by 35.4% of respondents. When asked to specify other barriers that were not reflected in the provided answer choices, respondents commonly referenced politics around gun control as a major barrier while another common response included not wanting to infringe on patients’ rights to own and use firearms. When asked to indicate which approach they thought would be most effective in counseling their patients on firearm safety, 69.7% said that universally screening patients using a validated screening tool would be the best option. Respondents also suggested routinely counseling patients with high-risk factors for gun violence, especially those with mental health disorders and children in the household; 59.3% of respondents were interested in receiving formal training on how to counsel patient on firearm safety if it were available to them, and 48.0% indicated that an online CME course would be the most effective way for them to learn how to provide firearm safety counseling.

We performed a χ2 test of independence to examine the relationship between demographic data and categorical variables. There was a statistically significant relationship between geographical region and the belief that firearm safety is a public health issue (X2 [9, N=1,099)]=24.89, P=.003). Overall, 100% of respondents from the New England region identified firearm safety as a public health issue. Also, 98.3% of respondents in the Pacific region of the country (WA, OR, CA, AK, and HI) also viewed firearm safety as a public health issue. The regions where respondents were less likely to view firearm safety as a public health issue included East South Central states (KY, TN, MS, and AL) and the West South Central (OK, AR, LA, and TX) with 82.9% and 90.7%, respectively. We also found that more respondents identifying as White (93.78%) were likely to have ever provided counseling to their patients on firearm safety compared to those from other racial/ethnic groups (X2 [3, N=1,087]=9.99, P<.02). However, no significant relationships were found between age or gender and whether respondents ever provided counseling to their patients.

The relationship between ever having provided firearm safety counseling and viewing firearm safety as a public health issue was statistically significant (X2 [1, N=1095]=26.11, P<.001). Those who viewed firearm safety as a public health issue were more likely to have provided firearm safety counseling, which is consistent with the current literature. Also, family physicians who had received some form of training on firearm safety counseling were significantly more likely to indicate a higher level of comfort with asking their patients about firearm ownership (X2 [5, N=1095]=31.17, P<.0001). Specifically, those who had received training through a residency curriculum were found to be more comfortable with asking patients about firearm ownership compared to those who had received no training at all.

The increased rate of accidental and intentional gun violence in the United States has risen in the past decade, prompting health care leaders to lend their voices to the debate on whether physicians should provide counseling on firearm safety to their patients. Current literature demonstrates that leaders from various medical specialties, including internal medicine, pediatrics, family medicine, and surgical subspecialties, have weighed in on this issue. However, although advocacy activities within these specific medical societies are pushing for more physician-initiated counseling on firearm safety, it is suggested that the political aspect of gun control and lack of education about firearm safety counseling may play a major role in preventing physicians from comfortably and openly discussing firearms with their patients. Primary care physicians are uniquely positioned to provide counseling on firearm safety as they are the critical access point for their patients and provide continuity of care that would afford them the opportunity to introduce such counseling during routine office visits. However, prior to this national survey study looking at the perceptions and experiences of family physicians on firearm safety counseling, there were limited data on whether primary care physicians provide such counseling and the perceived barriers to discussing this topic with their patients.

The majority of our study participants viewed firearm safety as a public health issue and also felt that family physicians should have the right to counsel patients on this topic, which is consistent with the existing literature on this topic. However, among our study participants, more than 90% reported that they have counseled patients on firearm safety at some point in their career, which is much higher than what has been previously reported. Other studies reported rates of less than 40%.9,10 Many of the participants in our study had received prior formal training on firearm safety counseling, with most receiving this education during their residency training. Those who had received formal training on firearm safety counseling were found to be more likely to report a higher level of comfort with asking their patients about firearm ownership. This information suggests that family medicine practitioners may benefit from receiving education on firearm safety counseling early in their training. Moreover, an online continuing medical education course may be the best training modality for family physicians facing time constraints in their practice.

Other important findings include study participants’ self-reported lack of comfort and knowledge with specific components of firearm safety counseling, such as educating high-risk patients about safety storage devices and safe removal of firearms from the home. This speaks to the need to increase teaching in these specific areas to family physicians. Moreover, our study found that primary barriers to firearm safety counseling included time constraints during office visits and the perception that patients did not want to receive counseling from their physicians on this topic. Additionally, our study participants felt that using a validated universal screening tool during office visits would be the most effective approach to providing counseling, which could also address the issue of time constraints and also help mitigate the discomfort physicians feel when addressing firearm safety with their patients.

This was a large national survey study of practicing family physicians on a topic for which limited data exists. The findings from this study suggest the need for more education around a much-needed practice among primary care providers. However, there are limitations to our study. This study had an overall 32.52% response rate, which was average, with a response rate of 92.7% for the specific firearm question set. Also, as this was a cross-sectional study, there is the potential for recall bias among survey respondents. Moreover, we were unable to verify whether study participants had ever actually provided firearm safety counseling because there is no consensus on what constitutes firearm safety counseling. Also, White females under the age of 50 years predominately comprised our study population, which raises the concern for lack of diversity among opinions of family physicians in this national survey study. Further, we found that respondents identifying as White were more likely to provide counseling on firearm safety. Due to the limited diversity of our study participants, this finding may not be representative of the general opinion held among family physicians regarding firearm safety counseling. Another major limitation is that the majority of our study participants reported less than 50% clinical time. This may limit the external validity of our study and therefore, limits our ability to broadly extrapolate the study findings to family physicians who have closer to 100% clinical time. However, since the participants in this study are also educators, despite their reported clinical time, they would be able to have the most impact when it comes to changing curricula to address firearm safety counseling among trainees.

Our study aims to inform practice changes in primary care settings where the provider has significant interaction with their patients and can provide continuous counseling on firearm safety over a longitudinal course. Therefore, this study has important clinical implications, especially for primary care providers who see patients with mental health disorders and those who have patients who are children living in households where firearms are stored and used.

This is a unique study that addresses a timely and relevant topic. Firearm safety is an important public health issue and more education is needed around physician-initiated firearm safety counseling. The findings in this study present an opportunity for medical providers to prepare a consensus statement on the need for formal education around firearm safety counseling. We encourage other medical specialties to conduct a similar study to survey their constituents to allow for the evidence to drive changes in their respective practices.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge Ojesh Upadhyay, MPH for his guidance and support with the χ2 statistical analysis.

References

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Firearm Mortality by State. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/pressroom/sosmap/firearm_mortality/firearm.htm. Accessed July 24, 2019.

- Betz ME, Wintemute GJ. Physician counseling on firearm safety: a new kind of cultural competence. JAMA. 2015;314(5):449-450. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.7055

- Committee on Injury, Violence, and Poison Prevention. Policy statement—role of the pediatrician in youth violence prevention. Pediatrics. 2009;124(1):393-402. doi:10.1542/peds.2009-0943

- Wintemute GJ, Betz ME, Ranney ML. Yes, you can: physicians, patients, and firearms. Ann Intern Med. 2016;165(3):205-213. doi:10.7326/M15-2905

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Gun Violence, Prevention of (Position Paper). https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/gun-violence.html. Accessed August 23, 2020.

- Hoops K, Crifasi C. Pediatric resident firearm-related anticipatory guidance: why are we still not talking about guns? Prev Med. 2019;124:29-32. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2019.04.020

- Zheng C, Mushatt D. Let’s join the lane: the role of infectious diseases physicians in preventing gun violence. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2019;6(3):ofz026. doi:10.1093/ofid/ofz026

- Lee MJ. On patient safety: "is there a gun in the home? Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2015;473(9):2765-2768. doi:10.1007/s11999-015-4307-9

- Barkin S, Duan N, Fink A, Brook RH, Gelberg L. The smoking gun. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1998;152(8). doi:10.1001/archpedi.152.8.749

- Grossman DC. Firearm injury prevention counseling by pediatricians and family physicians. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 1995;149(9):973. doi:10.1001/archpedi.1995.02170220039005

- Jones N, Nguyen J, Strand NK, Reeves K. What should be the scope of physicians’ roles in responding to gun violence? AMA J Ethics. 2018;20(1):84-90. doi:10.1001/journalofethics.2018.20.1.pfor2-1801

There are no comments for this article.