Background and Objectives: Patient identifiers are used in the opening lines of case presentations and written documentation in health care and medical education settings. These identifiers can reflect physicians’ implicit biases, which are known to impact patient care. Yet, no clear recommendations for the use of patient identifiers to reduce bias and stigma in patient care and medical education learning environments currently exist. We describe a process and outcomes for articulating such recommendations.

Methods: The University of Washington School of Medicine convened a group of diverse stakeholders to create patient identifier recommendations for use in the undergraduate medical education program. After a literature review, 22 recommendations for the use of patient identifiers were articulated. These underwent public comment periods reaching 11,150 potential respondents across our 5-state institution. Feedback from 437 respondents informed modifications to the recommendations. We used consensus methodology with three rounds of surveys and an expert group of 27 stakeholders to adopt recommendations with an a priori threshold of 90% agreeing the recommendation should be used.

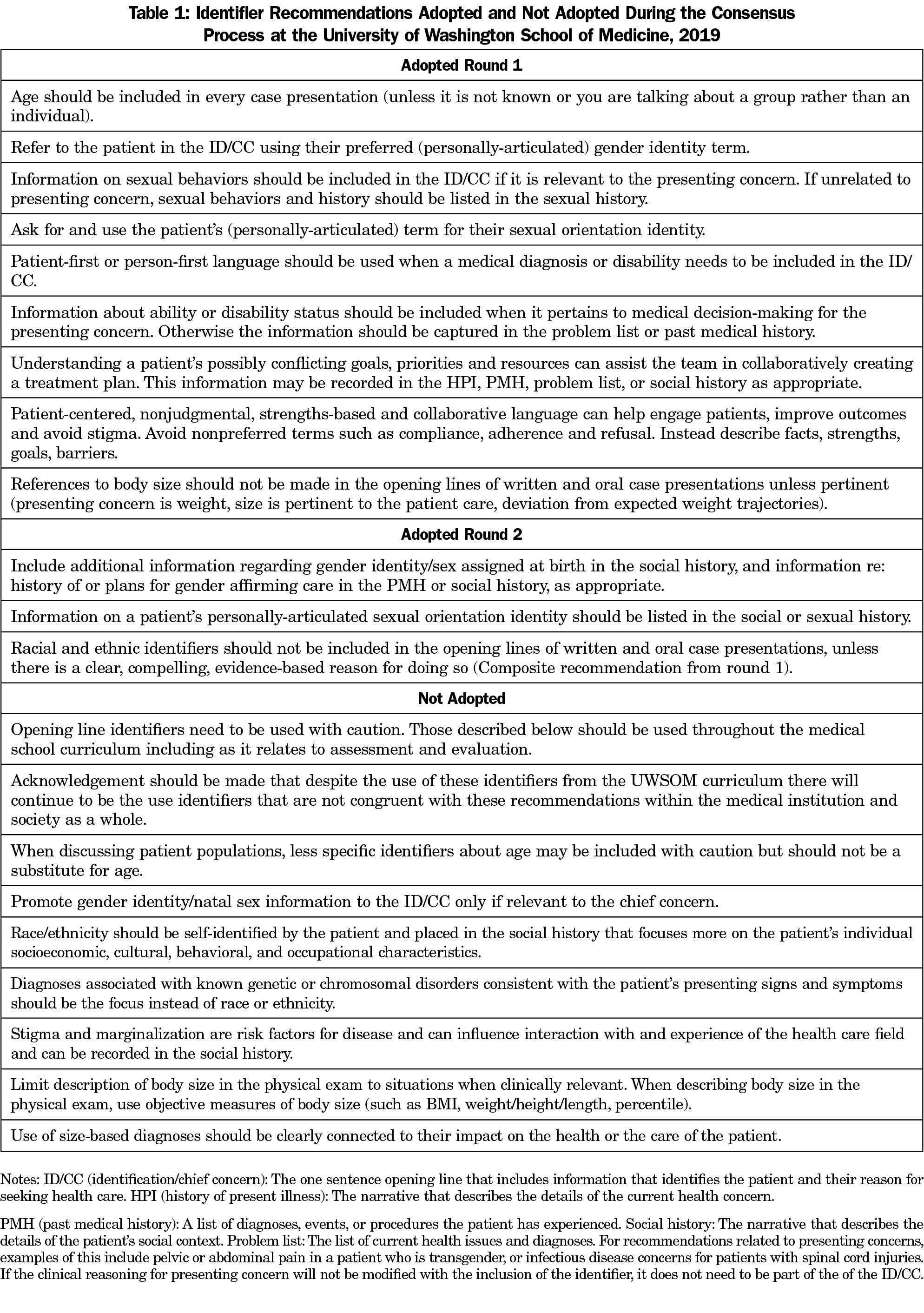

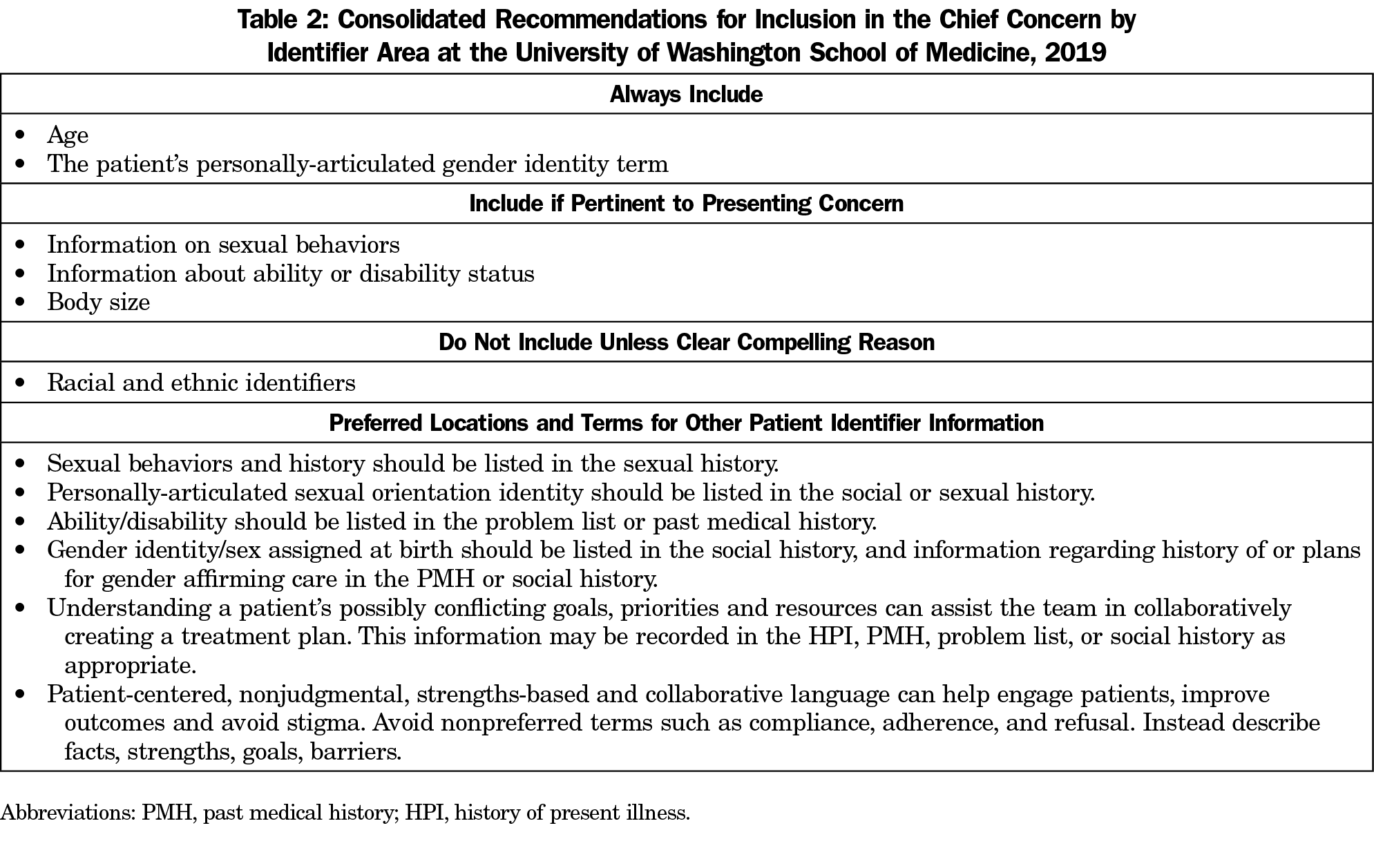

Results: We adopted 12 recommendations for patient identifiers for age, gender/sex, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, ability, size, and stigma; nine in round one, three in round two, and none in the third round.

Discussion: Our institution vetted these patient identifier recommendations via public comment and consensus methodology. Next steps include implementation across the undergraduate medical education program, including classroom and clinical settings. Other institutions could consider similar processes as key steps to reduce bias and stigma in their medical education programs.

Physicians use patient identifiers in the opening lines of case presentations and written documentation to efficiently communicate information about the patient’s identity that may be salient to their care. Identifiers allow recipients of patient information to rapidly engage in clinical reasoning about potential diagnoses and treatment plans. Patient identifiers can reinforce or dismantle implicit and explicit biases. Medical students learn professional skills through memorization and modeling of clinical preceptors, including case presentation formats; the importance of this educational process should not be underestimated. 1-15

The process that allows physicians to quickly diagnose patients can activate implicit bias, especially if identifiers used for patients are not thoughtfully selected. This can result in disparities in care along a variety of axes of identity. Differences in health-seeking behavior between heterosexual and sexual minority individuals result from fear of discrimination in the health care system.16-17 Implicit bias about race among pediatricians is associated with differences in treatment for asthma, pain, and attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder.18-20

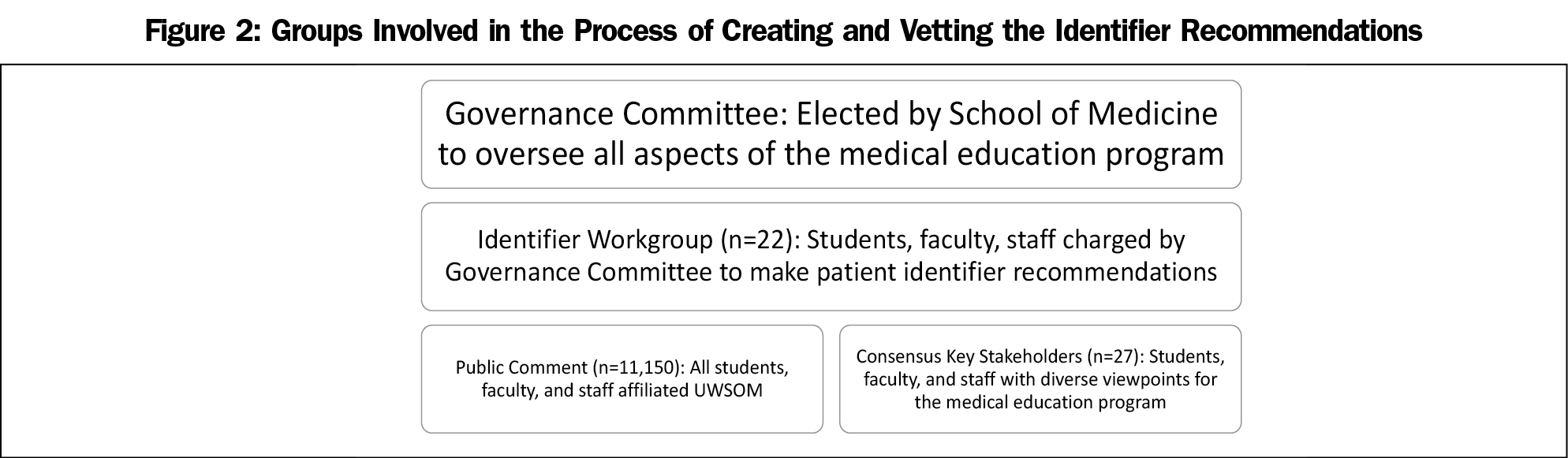

At the University of Washington School of Medicine (UWSOM), students and faculty noted inconsistency in identifier use within the preclinical curriculum that might promote bias and raised this concern to the UWSOM governance committee. This committee charged a faculty-led workgroup to create recommendations for the use of patient identifiers across the undergraduate medical education program, in both classroom and clinical settings, with a goal of decreasing bias.

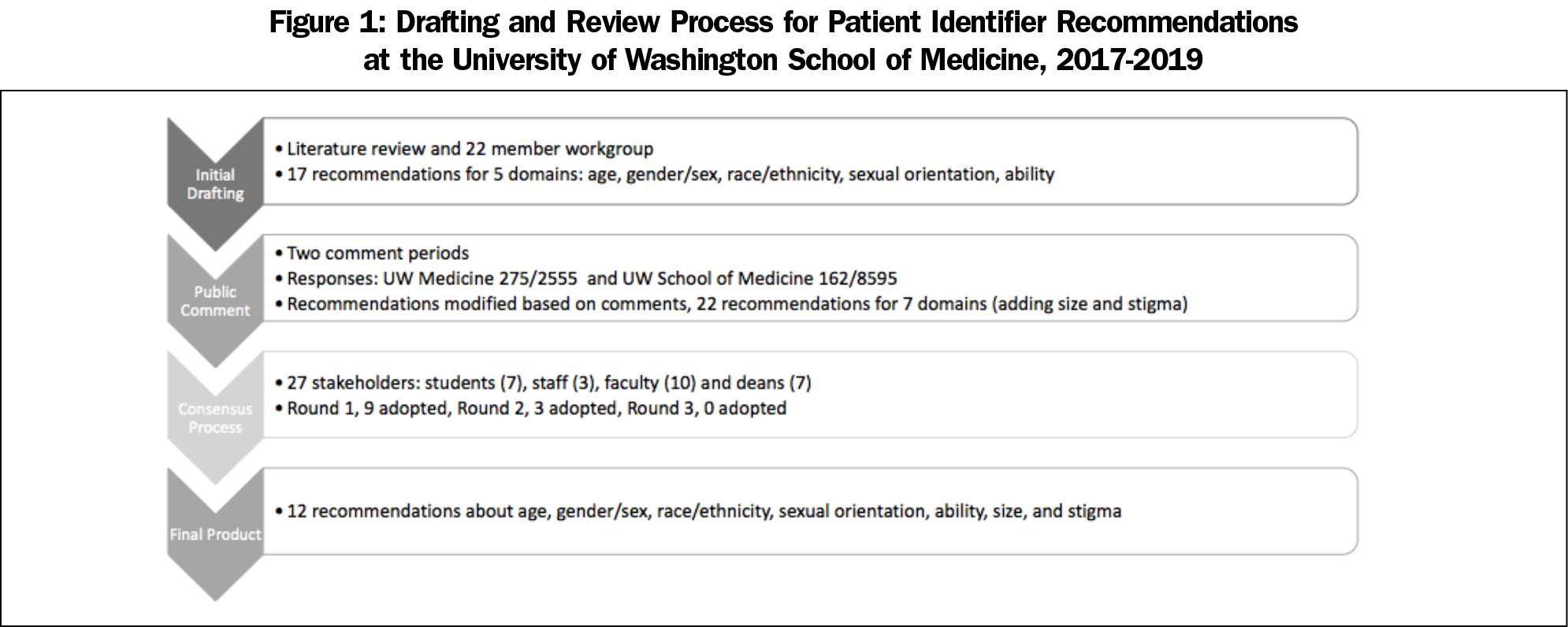

The Identifier Workgroup (IW) recruited 22 members from across Washington, Wyoming, Alaska, Montana and Idaho (WWAMI) sites, all 4 years of medical students, and different faculty and staff roles with an emphasis on diversity in lived and clinical experience. Subgroups performed a literature review with the aid of a health sciences librarian and drafted 17 identifier recommendations for the following areas: age, gender, race/ethnicity, sexual orientation, and disability status. The literature search included patient perspectives to ensure the recommendations were patient centered.

The IW gathered feedback on the recommendations through a public comment process open to all members of the institution based on a similar approach used by the US Preventive Services Task Force. To obtain public comment, the IW emailed an online survey and the draft recommendations to a listserv for students, and faculty and staff affiliated with UW Medicine. The survey was open for this group (total potential respondents=2,555) between July 10, 2018 and July 31, 2018. At the recommendation of the governance committee the IW expanded the population asked to provide public comment through distribution of the recommendations and survey to a listserv of all adjunct, affiliated, emeritus, and acting faculty, including fellows. The survey was open for this group (8,595 total potential respondents) between August 13, 2018 and August 20, 2018. Initial public comment indicated the need for recommendations about patient size and stigma and a set of five recommendations was created for these areas which underwent comment in the second round. We qualitatively organized feedback from the comments into themes that the IW used to modify the identifier recommendations. The final revised set comprised 22 unique identifier recommendations across seven areas of age,10,25,29 gender,3,4,16,17,22,24,34-36 race/ethnicity,2,6,8,26,32 sexual orientation,3,4,11,22,36 disability status,37 size,38 and stigma.39

To ensure the recommendations reflected the needs of the entire medial education program, the IW used a consensus approach with a group of key stakeholders (KS) made up students (7), staff (3), faculty (10), and deans (7), that reflected diversity in lived experience, clinical experience, and role in the medical education program across WWAMI.40 The KS were approved by the governance committee chairs and invited to participate in the consensus process. The consensus process involved three rounds of online surveys regarding inclusion, exclusion, and potential improvements for each of the 22 identifier recommendations. In each survey round, stakeholders received a document with all the identifier recommendations and explanatory text. KS were instructed to: “Indicate if you think each should be excluded or included. If you exclude or feel neutral about an identifier recommendation, please comment in the space provided.” Each recommednation was rated on a 5-point Likert scale from definitely include, possibly include, neutral, possible exclude, definitely exclude. The IW set an a priori adoption threshold at 90% of respondents rating an identifier either definitely or possibly include. After survey rounds one and two, stakeholders were given a list of recommendations they had adopted and the edited document with modified recommendations based on their feedback. Figure 1 outlines the process for patient identifier recommendation drafting and review. Figure 2 describes the different groups involved in this work. The UW Human Subjects Division deemed this study exempt from review.

The public comment resulted in 437 responses(275 from period one and 162 from period two), and respondents took an average of 31-39 minutes to complete feedback.

Nine identifier recommendations were adopted after round one of the consensus process (Table 1). After round two, three identifier recommendations were adopted (Table 1), one of which was a composite recommendation generated by combining two initial recommendations based on feedback in round one. No identifier recommendations were adopted in round three. Table 2 shows the recommendations for identifiers that should always be included, be included if pertinent, and not included unless there is a compelling reason. It also outlines preferred locations and terms for identity-based information in the medical database if this information is not included in the chief concern.

This is the first set of patient identifier recommendations that combined the approaches of literature review, institutional public comment period, and consensus methodology. As this set reflects our school, it may not be broadly applicable to other settings. However, our institution spans five states offering broad ideological and geographic representation. Next steps include implementation guidance for preclinical and clinical settings including faculty development. A document outlining approaches for preclerkship implementation was drafted and widely distributed via list-serves to faculty responsible for this part of the medical education program. A similar document is being drafted for the faculty responsible for the clinical elements (such as required and elective clerkships).

Strengths of this study include grounding the initial identifier recommendations in a literature review, the large number of individuals invited for public comment, and the use of consensus methods with key stakeholders. Weaknesses include a single institution and the low public comment response rate. This process did not address all possible patient identifiers. This study focused on patient identifiers, and although the work generated preferred locations for information that conveys important social and cultural information about the patient, this requires more study and elucidation. Respectful use of patient identifiers is evolving with the national conversation on issues related to these domains and use of these identifiers will require intentional revisiting and evolution over time.

Health inequities along the lines of identity persist. Identifiers used in medical education can perpetuate bias of health care providers that negatively impacts health outcomes. Informing students of practices to reduce bias and stigma can promote conscious habits to use when addressing patients.18,21,32 Physicians have an obligation to ensure the language used to describe patients is thoughtful and works to minimize instead of replicate bias. Elucidation of patient identifier recommendations for medical education is an important step for any institution, and this study provides an approach that can be replicated to build consensus.

There are no comments for this article.