Background and Objectives: A majority of medical students believe that treating sexual concerns is important for their careers. However, a minority feel that they have received adequate instruction in medical school. This novel supplemental reproductive and sexual health curriculum at a large academic medical center aimed to address this gap and to improve attitudes, comfort, and knowledge about sexual and reproductive health topics among learners.

Methods: Students participated in a series of sexual and reproductive health workshops taught by interdisciplinary health care workers, with the first cohort in a classroom setting and the second cohort using a virtual format due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We administered a novel pre- and

postcourse survey to assess attitudes, comfort, and knowledge about the topics. We performed unpaired 1-tailed t tests and χ2 tests to compare the scores on the pre- and postcourse surveys.

Results: Sample size was 12 students for the first cohort and 23 students for the second cohort. Reported levels of comfort with taking sexual histories in different age groups and discussing reproductive and sexual health topics increased significantly: 0.92 for the classroom setting, and 0.50 for the virtual setting, with an average increase of 0.65 points on a 4-point Likert scale. There were no significant changes in student attitudes toward or knowledge of reproductive and sexual health.

Conclusion: This course elaborated on topics to which medical students traditionally lack adequate exposure, with significant improvement in comfort counseling patients. A disparity between the classroom and virtual setting suggests limitations of online learning for these topics.

Sexual and reproductive health (SRH) is underrepresented in medical education.1,2 We designed an SRH workshop, entitled “Diversity in Reproductive Health and Human Sexuality,” to augment the curriculum at an academic medical center.

Lack of comfort and knowledge of SRH contributes to the inadequate delivery of related health care.3,4 Adolescent patients have noted low-quality discussions with their providers about sexual behaviors,5 and primary care physicians have felt unprepared discussing sexuality with aging adults.6 In family physicians, feeling embarrassed or lacking knowledge about sexual practices in LGBT patients hampered discussion of safe sexual practices.7

A review of national medical education shows that many sexual health curricula lack materials regarding sexual dysfunction, abortion, sexual practices, and sexual minority groups.1,8 Medical students and providers have historically expressed discomfort with taking sexual histories9 and assessing patients for sexual pleasure or dysfunction.10 In a 2009 study of medical students, 68.8% of students believed that treating sexual concerns would factor into their future careers, but only 37.6% felt they had received adequate instruction.11

At our institution, an electronically administered school-wide survey with 60 responses, constituting approximately 15% of the medical student body, illustrated that 96.7% of students hoped to learn more about reproductive options, but only 3.3% felt that this topic was very well represented in the formal curriculum. Based on national and local data, we aspired to create a curriculum to close this gap.

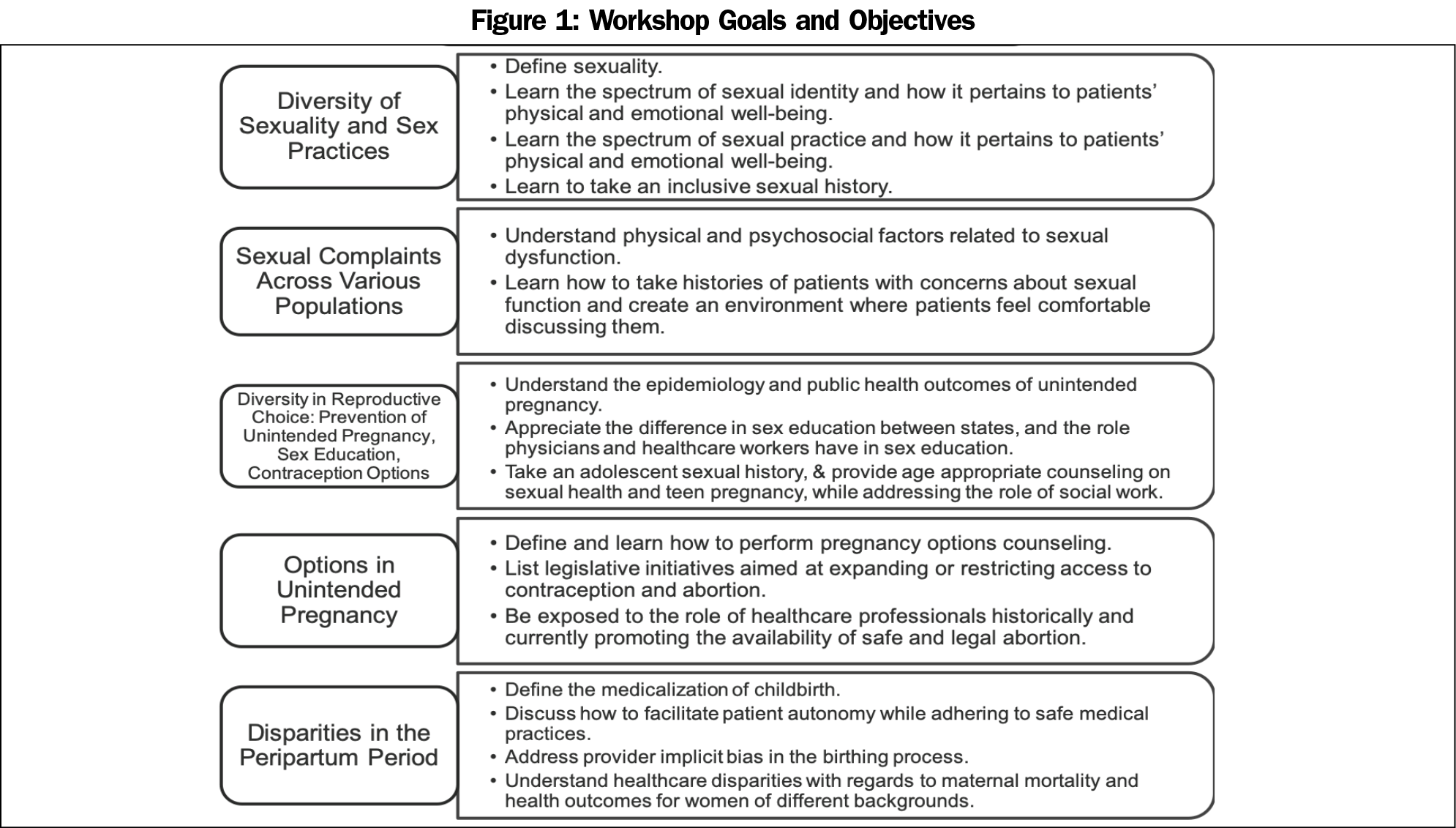

We designed a five-session workshop to cover topics found, upon review, to be absent or underrepresented in the 4-year curriculum at a New York City medical school. The workshop topics included sexuality, sexual practices, sexual dysfunction, contraception options, pregnancy options, and peripartum disparities (Figure 1). This pilot educational intervention was delivered over 2 years, once in a classroom setting and once virtually due to the COVID-19 pandemic. We offered the course to medical and physician assistant (PA) students who had completed their clinical curriculum. The course was taught by faculty and nonaffiliated providers. As anonymous education research, this study was exempted by Weill Cornell Medicine’s Institutional Review Board.

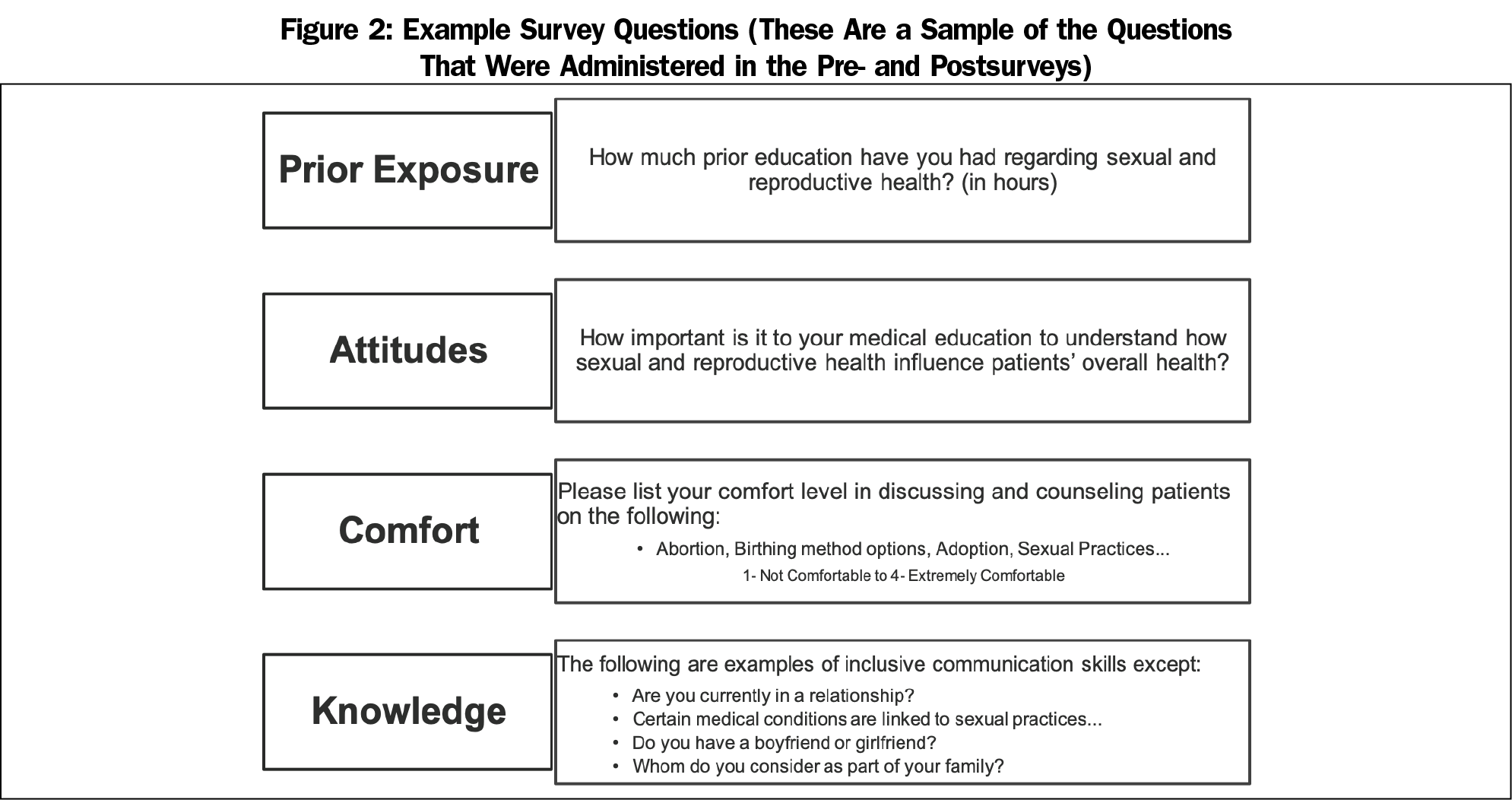

No validated tool existed to assess medical student comfort with and attitudes toward these topics. We designed a survey utilizing 4-point Likert scales that was administered before and after the course via online, anonymous surveys. For knowledge assessment, we administered a block of multiple-choice questions before and after the course for the first iteration, and following each session during the second to decrease latency bias (Figure 2). The survey had questions relating to prior education, attitudes toward the importance of SRH, and Likert scales assessing comfort counseling patients on course learning objectives (Figure 1). These categories are congruent with assessments in prior education literature. We included controls, such as comfort taking general medical histories. Data were pooled rather than paired, as this was a pilot series intended to assess efficacy of the course, and there was concern for high drop-out rates.

We performed unpaired one-tailed t tests or χ2 tests to compare the composite Likert scores between the pre- and postcourse surveys. We performed data analysis in Microsoft Excel.

The student sample size was 12 and 23 for the first and second sessions, respectively. The participants reported an average of 24 hours of prior instruction in SRH. The survey response rate was 100% in the first session, and ranged from 52% to 83% in the second due limitations of the virtual format. Student attitudes toward SRH did not change significantly; they rated the importance of understanding how SRH influences a patient’s overall health to be 4.77 (n=35) on a 4-point Likert scale prior, and 4.88 (n=25) after the elective (P=.44).

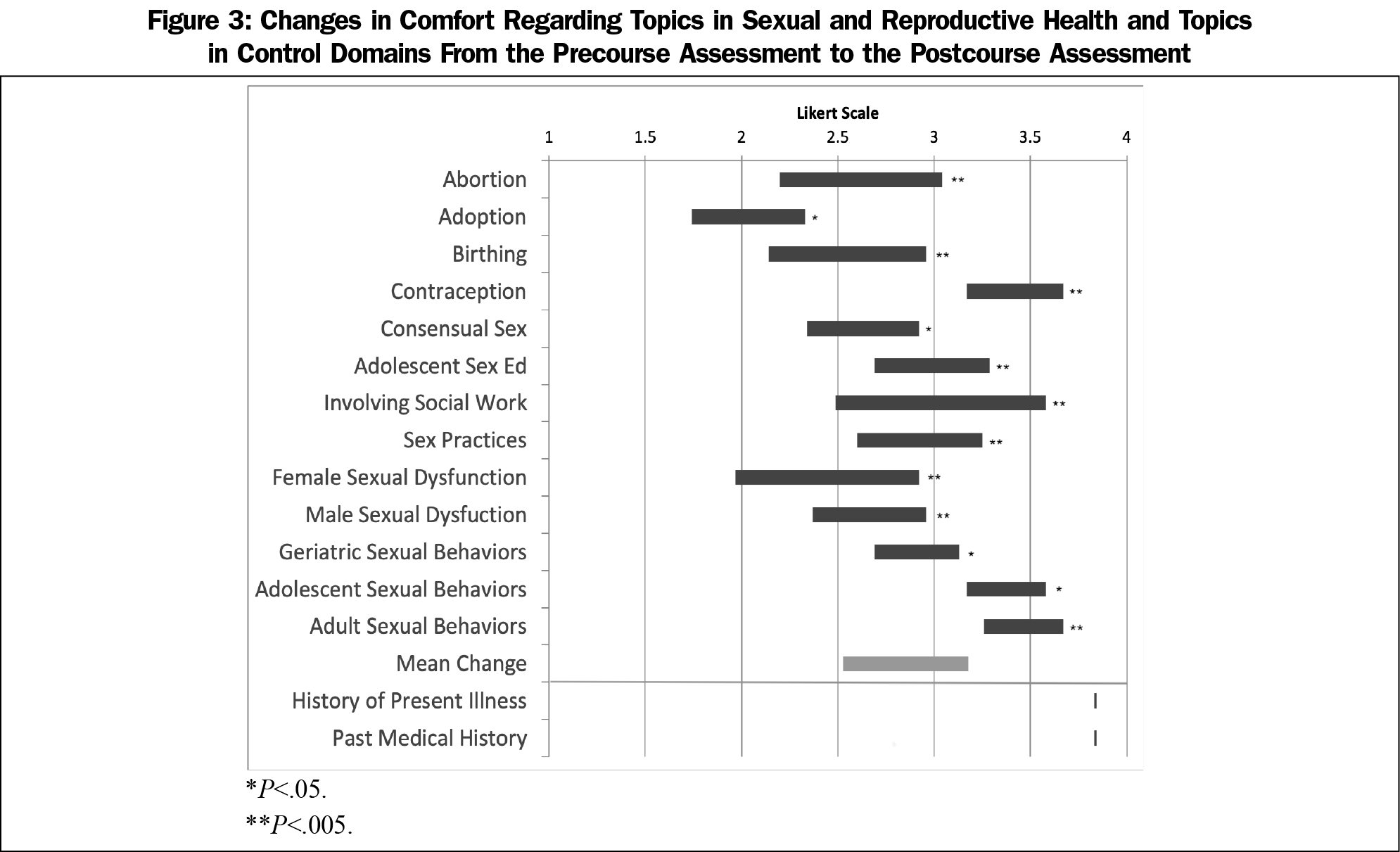

Students reported statistically significantly increased levels of comfort in counseling patients in pregnancy options, adolescent sex education, sexual dysfunction, and geriatric sexual behaviors. There was an average increase in comfort of 0.92 points after the first iteration, 0.50 points after the second, and 0.65 points on average. In contrast, reported levels of comfort with control domains did not significantly change (Figure 3).

Students scored an average of 54% on the knowledge questions prior to the workshop, and 60% after. In both sessions, knowledge scores calculated from before and after each lecture did not significantly differ (P=.14 in session one, P=.077 in session two).

Our SRH workshop improved comfort in counseling patients on SRH topics, but not attitudes toward or knowledge of the topics. This cohort’s initial discomfort addressing topics in SRH was congruent with the literature. Implementing this curriculum may improve comfort with this material and may be worthwhile as a supplement to the foundational curriculum.

Improvement in comfort was not as marked during the virtual iteration of the workshop as during the in-person iteration. Virtual sessions demonstrated decreased attendance and student engagement, as evidenced by poor survey response rates. The literature supports this observations, as a study assessing empathy in SSRI-related sexual dysfunction found that in-class learning vs an online module was associated with a higher level of empathy.12 Further research is needed to determine how method of course delivery affects student learning.

The study had several limitations. The self-selecting nature of the cohort may have contributed to a nonsignificant change in attitudes and a lack of generalizability. Students engaged in the optional workshops already had a positive attitude toward the topics. The lack of significant change in knowledge may have had multiple factors: a lack of incentive to complete surveys, the prolonged time in between the survey administrations in the first iteration, and the impaired attentiveness in the virtual format. The lack of paired data and variable response rates led to less power in assessing change in the study’s measures. Additionally, the questions were not systematically validated, limiting the study’s accuracy.

Nonetheless, this study shows how didactic sessions can improve comfort with SRH topics. Future studies will aim to create a validated survey instrument and investigate longitudinal preparedness for patient encounters. Fostering future health care professionals trained in addressing SRH can decrease barriers to nonjudgmental, comprehensive health care.

Acknowledgments

Ms Friedlander and Ms Mou served as co-first authors and contributed equally to this work.

Presentations: Content from this manuscript was presented at the 20th Annual Fall Scientific Meeting of Sexual Medicine Society of North America, October 2019 in Denver, Colorado.

Funding Statement: This work was made possible by grants from the Health Equity Fund at Weill Cornell Medical College, the President’s Council for Cornell Women Microgrant at Cornell University, and the Primary Care Innovations Grant from the Division of Internal Medicine at Weill Cornell Medicine.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are those of the authors and not an official position of Weill Cornell Medical College or the grant providers. None the authors have any conflicts of interest to disclose.

References

- Shindel AW, Baazeem A, Eardley I, Coleman E. Sexual health in undergraduate medical education: existing and future needs and platforms. J Sex Med. 2016;13(7):1013-1026. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2016.04.069

- Eardley I, Reisman Y, Goldstein S, Kramer A, Dean J, Coleman E. Existing and future educational needs in graduate and postgraduate education. J Sex Med. 2017;14(4):475-485. doi:10.1016/j.jsxm.2017.01.014

- Parish SJ, Rubio-Aurioles E. Education in sexual medicine: proceedings from the international consultation in sexual medicine, 2009. J Sex Med. 2010;7(10):3305-3314. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2010.02026.x

- Shindel AW, Ando KA, Nelson CJ, Breyer BN, Lue TF, Smith JF. Medical student sexuality: how sexual experience and sexuality training impact U.S. and Canadian medical students’ comfort in dealing with patients’ sexuality in clinical practice. Acad Med. 2010;85(8):1321-1330. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181e6c4a0

- Fuzzell L, Shields CG, Alexander SC, Fortenberry JD. Physicians talking about sex, sexuality, and protection with adolescents. J Adolesc Health. 2017;61(1):6-23. doi:10.1016/j.jadohealth.2017.01.017

- Hughes AK, Wittmann D. Aging sexuality: knowledge and perceptions of preparation among U.S. primary care providers. J Sex Marital Ther. 2015;41(3):304-313. doi:10.1080/0092623X.2014.889056

- Pujalte GGA, Effiong II, Nishi LYM, Clapp ADM, Waller TA. Primary care perceptions and practices on discussion and advice regarding sexual practices. South Med J. 2020;113(7):356-359. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001114

- Shindel AW, Parish SJ. Sexuality education in North American medical schools: current status and future directions. J Sex Med. 2013;10(1):3-17. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02987.x

- Malhotra S, Khurshid A, Hendricks KA, Mann JR. Medical school sexual health curriculum and training in the United States. J Natl Med Assoc. 2008;100(9):1097-1106. doi:10.1016/S0027-9684(15)31452-8

- Sobecki JN, Curlin FA, Rasinski KA, Lindau ST. What we don’t talk about when we don’t talk about sex: results of a national survey of U.S. obstetrician/gynecologists. J Sex Med. 2012;9(5):1285-1294. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2012.02702.x

- Wittenberg A, Gerber J. Recommendations for improving sexual health curricula in medical schools: results from a two-arm study collecting data from patients and medical students. J Sex Med. 2009;6(2):362-368. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2008.01046.x

- Palmer BA, Lee JH, Somers KJ, et al. Effect of in-class vs online education on sexual health communication skills in first-year medical students: a pilot study. Acad Psychiatry. 2019;43(2):175-179. doi:10.1007/s40596-018-0949-8

There are no comments for this article.