Background and Objectives: Active learning, defined as a variety of teaching methods that engage the learner in self-evaluation and personalized learning, is emerging as the new educational standard. This study aimed to evaluate how family medicine clerkship directors are incorporating active learning methods into the clerkship curriculum.

Methods: Data were collected via a Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance survey of family medicine clerkship directors. Participants answered questions about the number and type of teaching faculty in their department, the various teaching methods used in their family medicine clerkship, and what challenges they had faced in implementing active learning methods.

Results: The survey response rate was 64%; 97% of family medicine clerkships use active learning techniques. The most common were online modules, problem-based learning, and hands-on workshops. The number of teaching faculty was significantly correlated with hours spent in live (not online) active teaching. One-third of clerkship directors felt challenged by lack of resources for adopting active learning. Clerkship directors did not cite lack of expertise as a challenge to implementing active learning. Time dedicated to clerkship director duties or the presence of a dedicated educator in the department was not associated with the adoption of active learning.

Conclusions: The use of active learning in the family medicine clerkship is required both by educational standards and student expectations. Clerkship directors may feel challenged by lack of resources in their attempts to adopt active learning. However, there are many methods of active learning, such as online modules, that are less faculty time intensive.

There is a movement in medical education to promote active learning techniques over traditional lectures. Active learning describes a variety of approaches, including workshops, online modules, team-based learning, and flipped classrooms.1 Active learning is designed to maximize student engagement, requires self-directed learning, and teaches lifelong learning skills. These student-centered methods may require evaluating learners prior to a session, and adjusting the content to best meet learners’ needs. It is resource intensive to design and facilitate an active learning curriculum.

A meta-analysis of 225 studies reported that active learning in universities improved student performance and reduced odds of failing.3 However, evaluation of active learning methods in medical education has yielded equivocal results. Studies with medical students have shown active learning modules result in similar knowledge gain as traditional methods,4 or similar knowledge gains but improved application skills.5 Student satisfaction with active learning is variable.4-7 Reasons cited for low student satisfaction include the perception that lectures are more efficient, and frustration caused by inconsistent faculty quality or inadequate preparation by peers.4,7

Despite these mixed results, the incorporation of active learning is mandated by curriculum oversight authorities.6 This study evaluated how clerkship directors are implementing active learning, what challenges they face, and what resources, including faculty time, may facilitate this transition.

Survey

Data were gathered as part of the 2020 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine clerkship directors distributed annually to clerkship directors at accredited North American medical schools.8 The survey was emailed to 147 US and 16 Canadian family medicine clerkship directors in June 2020, using SurveyMonkey. Nonrespondents received multiple reminders. The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved this study in May 2020.

Survey Questions

Participants answered questions regarding percent time as clerkship director, whether their department had a nonphysician educator or physician who completed education training, number of teaching faculty, hours of didactics, hours of active learning methods, types of active learning methods, and challenges to adoption of active learning.

Analyses

We summarized study variables using descriptive statistics. Bivariate correlations determined associations between number of teaching faculty, percent time as clerkship director, and time spent using active learning methods. We defined active learning as any method other than large group lecture. We calculated the percent of time teaching active learning by dividing the number of hours spent using active methods in both large group and small group settings by the total number of didactic hours. We used a t test to determine whether there were differences in time teaching using active learning methods if the department had a faculty member with training in education.

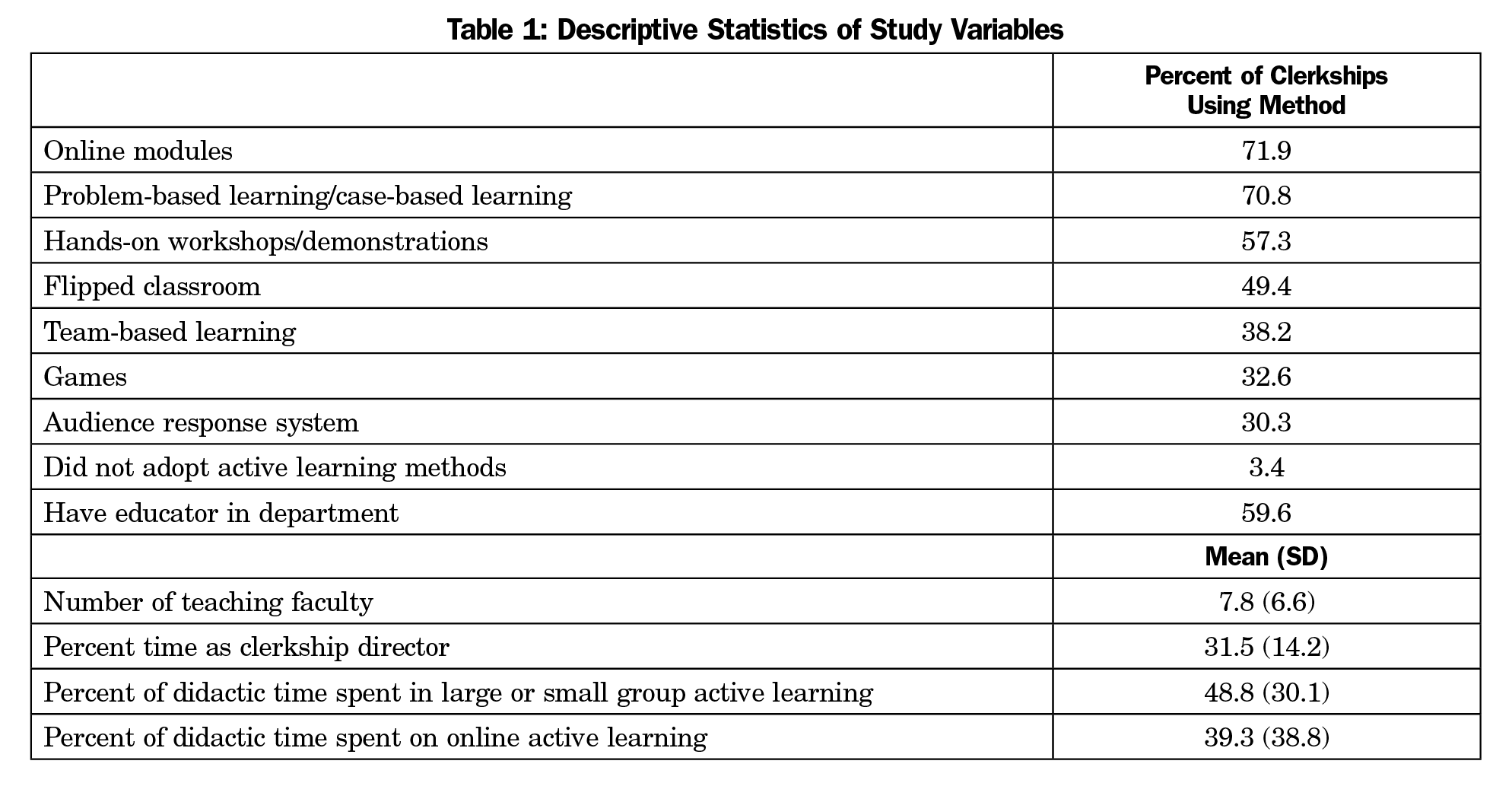

A total of 105 of 163 clerkship directors responded, for a response rate of 64.4%. Descriptive statistics are presented in Table 1. Sixteen respondents did not complete the survey and were removed.

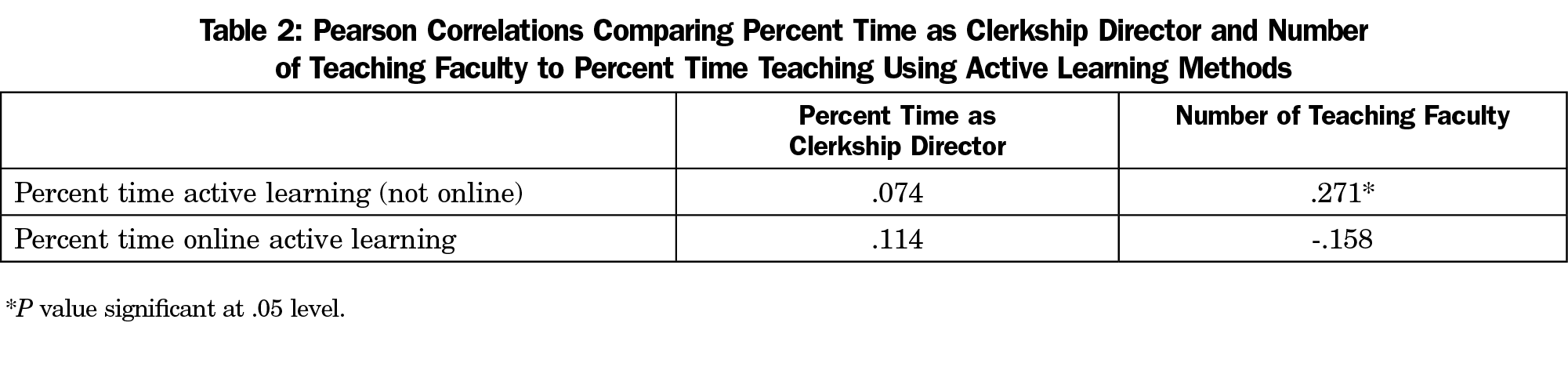

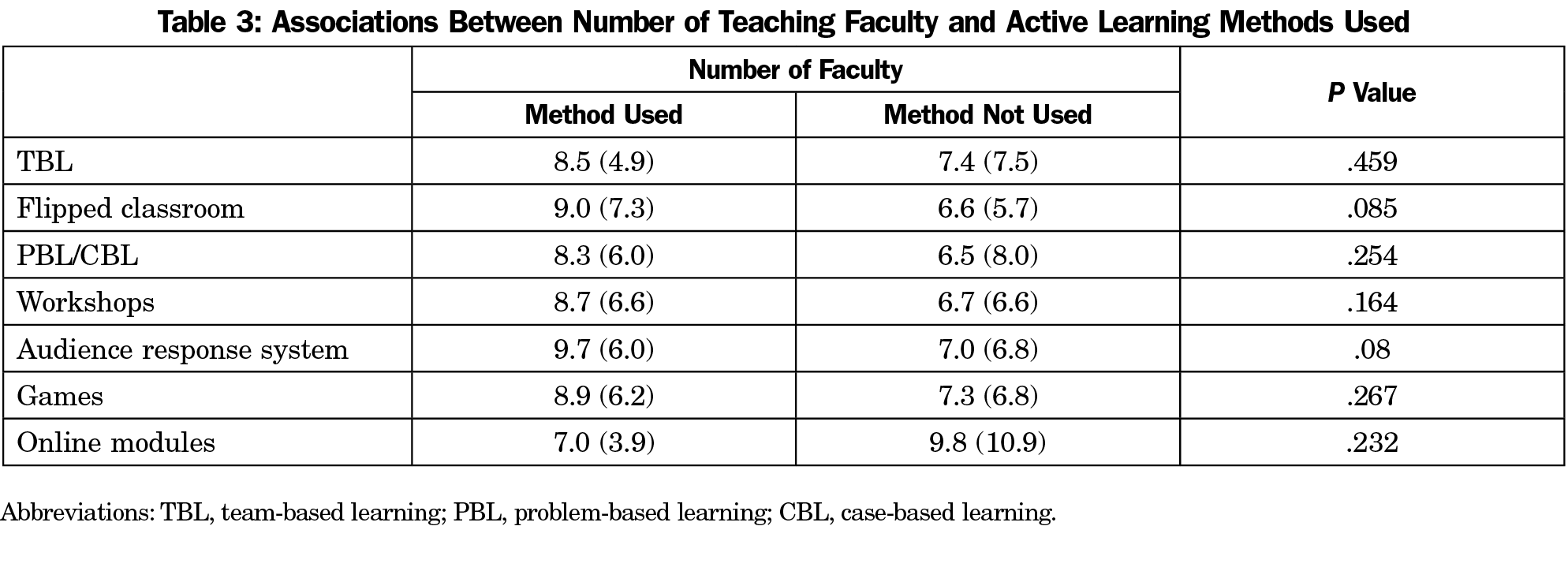

Correlations showed that the number of teaching faculty was positively associated with the percent of didactic time spent using active learning, but not with percent time using online modules. No significant correlations were found between clerkship director full-time equivalent (FTE) and percent time using active learning methods or online active learning (Table 2). t test showed departments with an educator did not spend a greater percentage of their time (46.9%) on active learning than departments without an educator (51.5%, P=.478). t tests also showed no associations between number of teaching faculty and type of active learning methods used (Table 3).

When asked about challenges clerkship directors faced, 33.7% reported lack of resources and 28.1% said their students were too geographically dispersed to adopt active learning methods, but 43.8% reported they adopted active learning methods without major challenges. Only 7.9% said they didn’t have the expertise to adopt active learning methods.

The more teaching faculty a department had, the more didactic time they spent using live active learning methods. However, the number of teaching faculty was not associated with time spent using online active learning methods. Perhaps larger departments can spend more faculty time in either large- or small-group active learning rather than using online modules, which require little faculty time. Although most respondents had adopted some learning methods, approximately one-third felt challenged by a lack of resources. Major challenges of some active learning methods are the amount of time to prepare for them and the faculty required to teach them.9

Resources for implementing active learning strategies include manpower, technology, and expertise. In contrast to a 2016 study,10 our findings indicate that perceived lack of expertise was not a problem in the adoption of active learning. There was a correlation between the number of teaching faculty and the percent of didactic time spent in live (large or small group) active learning activities, implying that departments with more teaching faculty could devote more faculty time to teaching. There was no association between the number of teaching faculty and using online modules. Departments with limited teaching faculty can adopt some aspects of active learning with less faculty burden than small-group teaching. Neither the presence of an educator nor the FTE dedicated to the clerkship director role were associated with time spent using active learning. Changing those variables is not likely to influence the adoption of active learning.

This study did not inquire about specific technology needs for adopting active learning. These may include the presence of a technology specialist, adequate hardware such as cameras or laptops, or the availability of high-speed internet in remote locations. As online resources become more ubiquitous and user friendly, the technology burden to the medical school may decrease. However, many of these resources require subscription fees that must be borne by the institution or students. One area for future research is the added cost of subscription fees and the perceived utility to medical students.

Active learning methods in medical education are the educational standard, both from an educational research1 and from the student perspective.7 Didactics continue to be important to ensure educational equivalency across multiple clinical sites. This study demonstrates there is a wide variety of teaching methods that qualify as active learning. Individual medical schools should consider the availability of teaching resources when deciding how to incorporate active learning techniques into their curricula.

References

- McCoy L, Pettit RK, Kellar C, Morgan C. Tracking Active Learning in the Medical School Curriculum: A Learning-Centered Approach. J Med Educ Curric Dev. 2018;5:2382120518765135. doi:10.1177/2382120518765135

- Mann KV. Theoretical perspectives in medical education: past experience and future possibilities. Med Educ. 2011;45(1):60-68. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2010.03757.x

- Freeman S, Eddy SL, McDonough M, et al. Active learning increases student performance in science, engineering, and mathematics. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(23):8410-8415. doi:10.1073/pnas.1319030111

- Prunuske AJ, Henn L, Brearley AM, Prunuske J. A Randomized Crossover Design to Assess Learning Impact and Student Preference for Active and Passive Online Learning Modules. Med Sci Educ. 2016;26(1):135-141. doi:10.1007/s40670-015-0224-5

- Everard KM, Schiel KZ. Learning Outcomes From Lecture and an Online Module in the Family Medicine Clerkship. Fam Med. 2020;52(2):124-126. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.211690

- Cooke M, Irby D, O’Brien B. Educating physicians. A call for reform of medical school and residency. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass; 2010.

- Walling A, Istas K, Bonaminio GA, et al. Medical Student Perspectives of Active Learning: A Focus Group Study. Teach Learn Med. 2017;29(2):173-180. doi:10.1080/10401334.2016.1247708

- Seehusen DA, Mainous AG III, Chessman AW. Creating a Centralized Infrastructure to Facilitate Medical Education Research. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257-260. doi:10.1370/afm.2228

- Morris J. The use of team-based learning in a second year undergraduate pre-registration nursing course on evidence-informed decision making. Nurse Educ Pract. 2016;21:23-28. doi:10.1016/j.nepr.2016.09.005

- Tsang A, Harris DM. Faculty and second-year medical student perceptions of active learning in an integrated curriculum. Adv Physiol Educ. 2016;40(4):446-453. doi:10.1152/advan.00079.2016

There are no comments for this article.