Background and Objectives: Increasing the number of underrepresented minorities in medicine (URM) has the potential to improve access and quality of care and reduce health inequities for diverse populations. Having a diverse workforce in residency programs necessitates structures in place for support, training, and addressing racism and discrimination. This study examines reports of discrimination and training initiatives to increase diversity and address discrimination and unconscious bias in family medicine residency programs nationally.

Methods: This survey was part of the Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) 2018 national survey of family medicine residency program directors. Questions addressed the presence of reported discrimination, residency program training about discrimination and bias, and admissions practices concerning physician workforce diversity. We performed univariate and bivariate analyses on CERA survey response data.

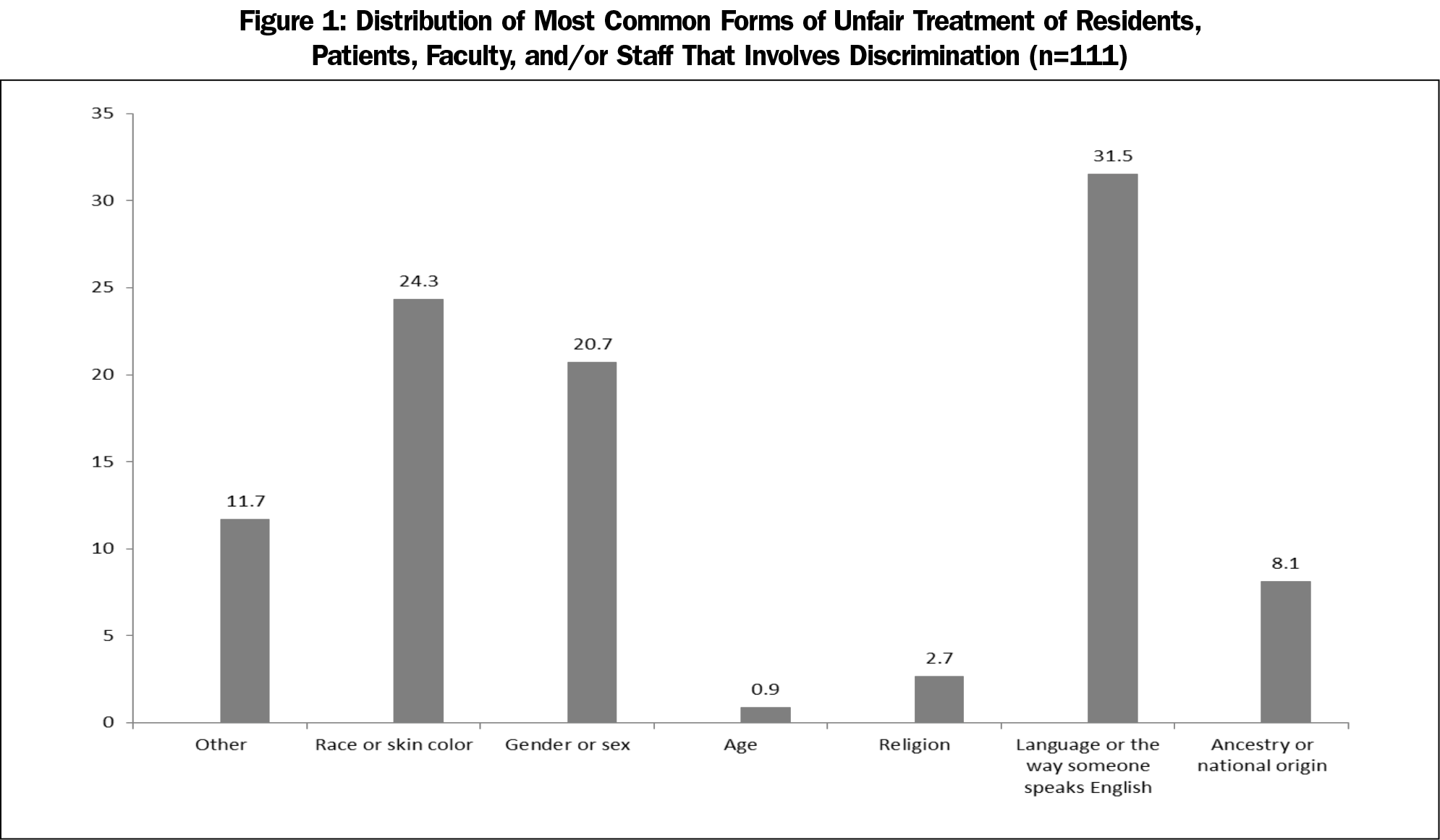

Results: We received 272 responses to the diversity survey items within the CERA program director survey from 522 possible residency director respondents, yielding a response rate of 52.1%. The majority of residency programs (78%) offer training for faculty and/or residents in unconscious/implicit bias and systemic/institutional racism. A minority of program directors report discrimination in the residency environment, most often reported by patients (13.2%) and staff (7.2%) and least often by faculty (3.3%), with most common reasons for discrimination noted as language or race/skin color.

Conclusions: Most family medicine residency program directors report initiatives to address diversity in the workforce. Research is needed to develop best practices to ensure continued improvement in workforce diversity and racial climate that will enhance the quality of care and access for underserved populations.

Diversity in the underrepresented in medicine (URM) physician workforce lags far behind the general population, with the percentage of Black individuals in the physician workforce at less than half the percentage in the general population (5.82% vs 12%).1 Accrediting agencies for both undergraduate and graduate medical education programs (LCME2 and ACGME3) have recognized this discrepancy and mandated initiatives to address the workforce needs.4,5

Increasing the number of URM is important in addressing health care disparities through improved access and quality. Members of minority groups are less likely to be able to access culturally-similar health care providers.6 Patients from underrepresented groups often experience discrimination in the health care system that leads to decreased quality of care and worse health outcomes.7,8 In addition, URM health care professionals experience discrimination from patients,9 raising ethical issues regarding treatment obligations, social justice, and personal integrity. Previous studies demonstrate that discrimination is underreported10 yet common among URM residents,11-13 faculty14,15 and staff. Therefore, beyond increasing the number of URM residents, programs need to put structures in place for support, training, and addressing racism and discrimination.

Interventions at multiple levels are necessary to address these deficits and reduce discrimination.16,17 Individual residency programs in multiple specialties, including family medicine, have reported initiatives to address diversity18-27 that include antidiscrimination efforts, training on implicit bias, and holistic reviews for admissions. We assessed the national status of reported discrimination in educational and clinical environment and efforts to integrate training in diversity and inclusion training within programs. We hypothesized that residency programs offer insufficient training in unconscious/implicit bias and systemic racism and that programs with a more diverse resident pool have more identified discrimination.

Sample and Survey

We conducted a cross-sectional study of US family medicine residency program directors (PDs). Diversity questions were part of a larger 2017 omnibus Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey for PDs. The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved the study. We collected data from January to February 2018. The CERA survey and methodology have been described previously.28 The overall response rate for the survey was 57.1% (298/522), and 272 respondents completed the diversity survey for a 52.1% response rate.

Measures

The primary variables of interest were discrimination complaints in the training environment by patients, residents, faculty, and/or staff (four items), the most common forms of discrimination complaints (race, gender, age, religion, national origin, and language; one item), and the existence of policies in place to address discrimination (one item).

We collapsed response options for the four questions about discrimination incidents due to cell sizes and coded as 1=often/sometimes, and 0=rarely/never. We summed responses (range 0-4) for the four discrimination questions (patients, staff, residents, and faculty).

Analysis

We performed analyses using STATA 13.1 software (College Station, TX). We conducted univariate statistics and bivariate statistics to examine the relationships between the discrimination and recruitment strategies with PD and program characteristics. We used χ2 tests to assess significance for categorical comparisons, and analysis of variance tests to examine continuous variables.

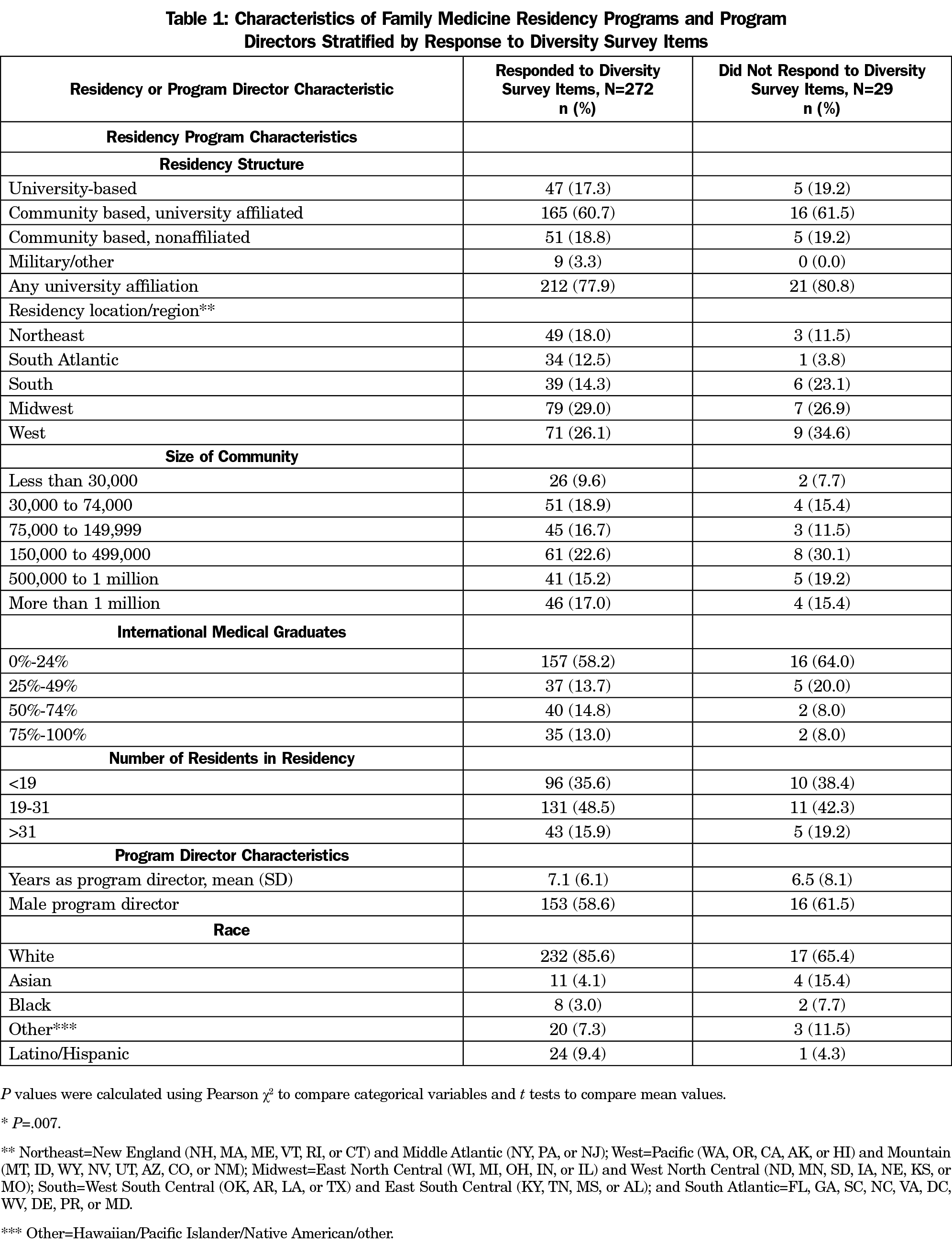

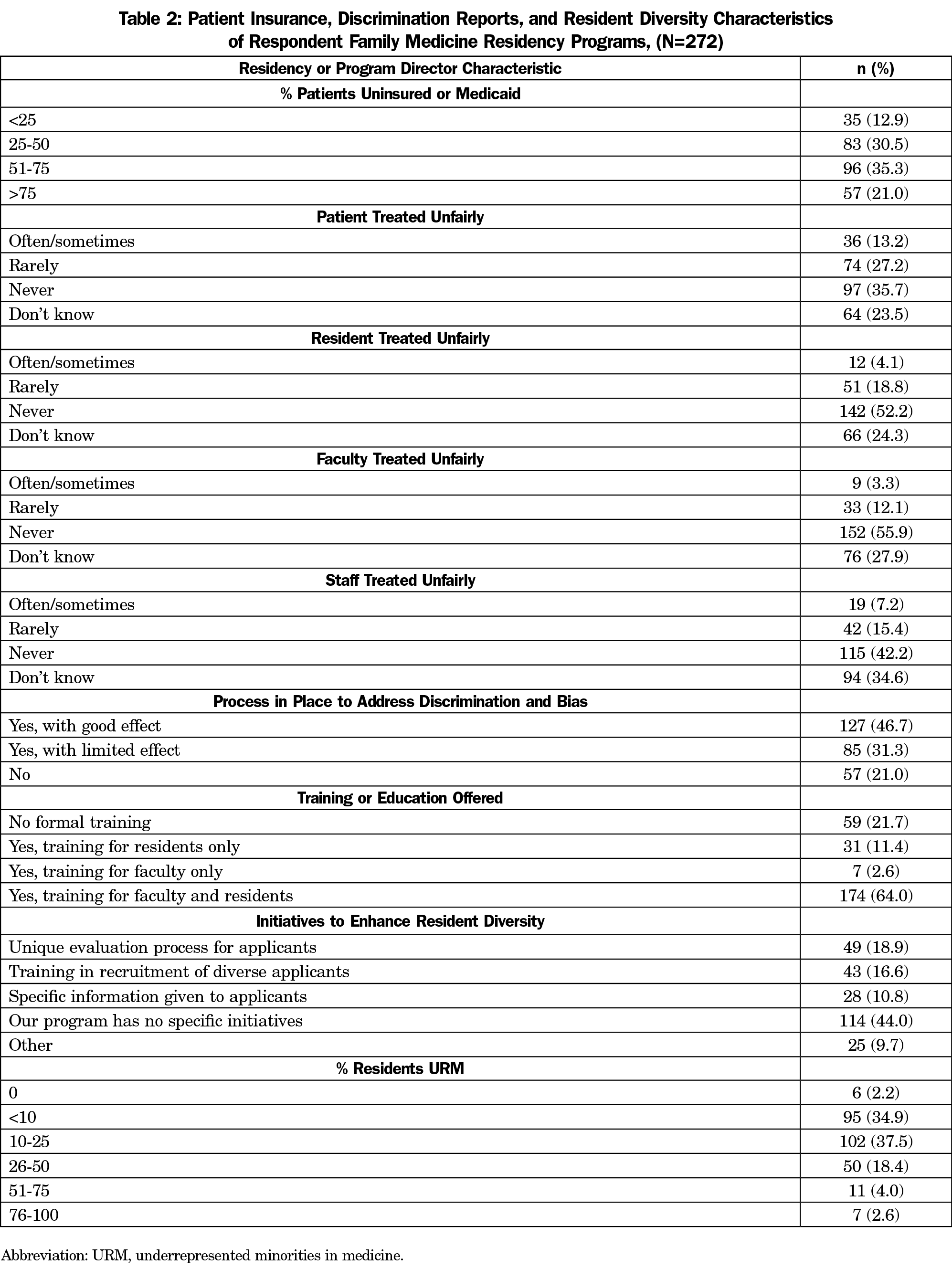

Table 1 shows the characteristics of respondent family medicine residency programs and PDs. Table 2 summarizes discrimination reports, resident diversity characteristics, and initiatives of respondent family medicine PDs and residency programs. One in five programs reported no process in place to address discrimination and bias. Fewer than half of programs (46.7%) reported a good effect from their process to address discrimination and bias. Among PD respondents, 41% (111/272) answered affirmatively (often/sometimes) that there were complaints by patients, staff, residents, and faculty (in decreasing numbers) related to racism/discrimination.

Figure 1 illustrates the frequency of most common forms of reported unfair treatment involving discrimination. The most commonly identified reasons for discrimination related to language, race/skin color, gender, ancestry, or national origin (in decreasing order of frequency).

Seventy-eight percent of PDs reported having training or education about unconscious/implicit bias and/or systemic racism/discrimination for residents and/or faculty in their programs.

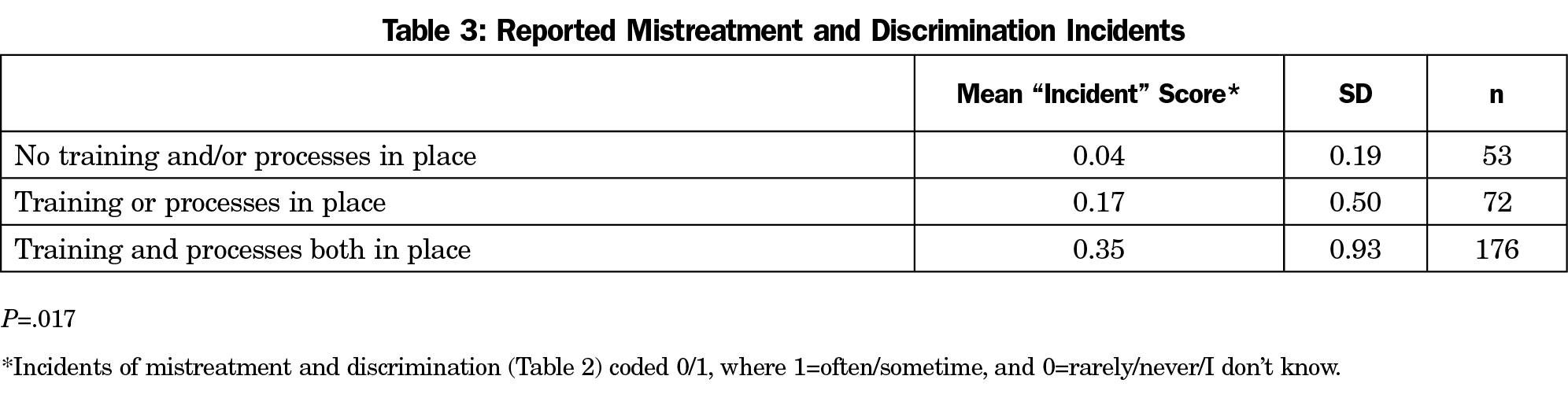

A higher amount of reported discrimination was significantly associated (unadjusted, P=.02) with residency programs having training and/or processes in place to address discrimination (Table 3).

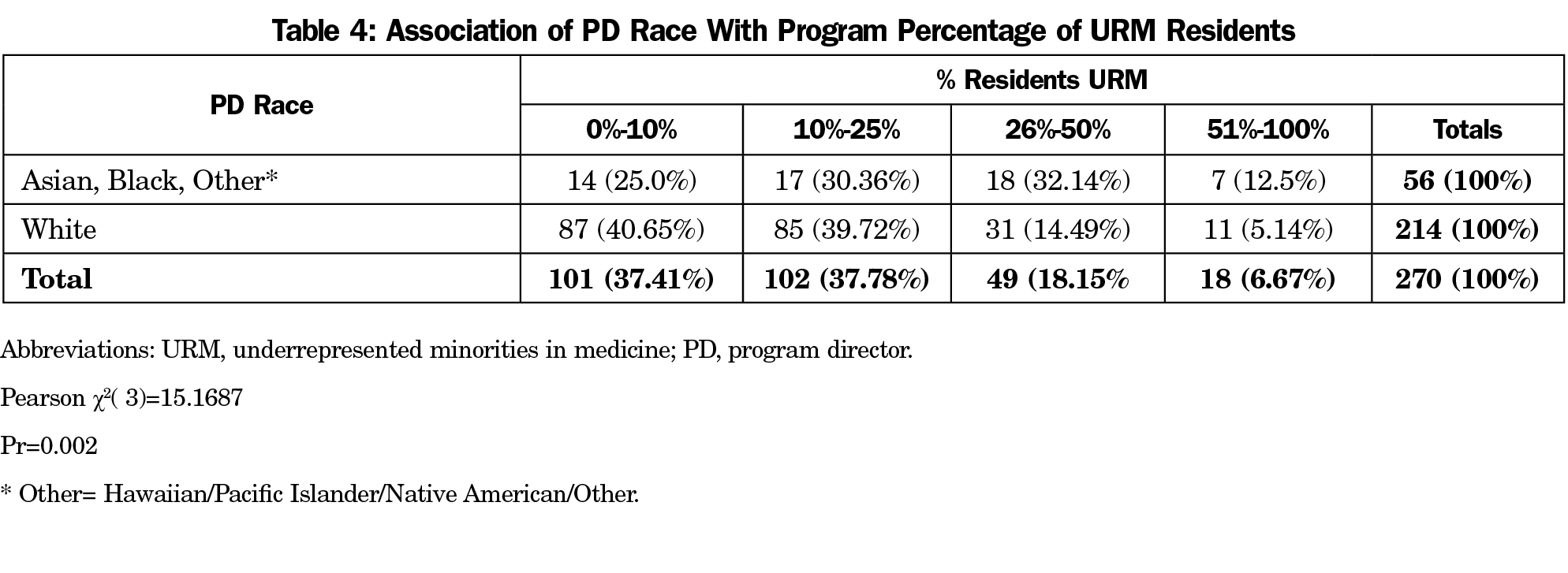

Neither the gender nor the race/ethnicity of the program director made a significant difference in the reporting of initiatives to increase diversity, reportage of discrimination, or training about diversity. However, the race/ethnicity of the program director had a consistent correlation with percentage of URM residents in a program, with 45% of program directors of color (25/56) reporting over 25% residents of color while only 20% of White program directors (42/214) reported such diversity (Table 4).

Increasing the number of URMs in medicine has the potential to improve access and reduce the prevailing inequities that characterize both health and medical care in the United States today. In this survey, programs with a more diverse resident pool had more identified discrimination. PDs perceived that the most common forms of discrimination experienced by residents, faculty, and staff were directed to language (or characteristics of spoken English), race, and gender. While the majority of programs had processes in place to address discrimination and bias, half of the PDs believed they had limited or no effect. Additionally, the findings raise the possibility that discrimination is underreported in programs without processes in place to address discrimination.

Given persistent and increasing health inequities, the increasing racial and ethnic demographics of our country, the paucity of URM physicians, and the rise of racial tensions in the United States, programs will require structural changes beyond admitting more URM trainees to address discrimination and train faculty and residents in antioppression skills. Residents who experience discrimination or witness unaddressed discrimination toward patients, faculty, and staff from their same communities might conclude that they themselves do not belong in the program or the profession. Recruiting more URM trainees who do not feel welcome without structures in place to address prevailing racism may negatively impact retention and future recruitment.

Limitations

Our study has limitations, including the overall response rate. Although this response rate is similar to previous published CERA studies, the results may not be generalizable to other specialties and nonresponders. Survey data is self-reported and subject to response bias and socially desirable answers. Discrimination reports only from the PDs’ perspective likely underestimates the extent of discrimination within the training setting. The survey did not evaluate the racial composition of the staff, faculty, or population. The variation in composition of programs and communities may affect study findings.

The survey was administered in 2018. Recent national social unrest following the death of George Floyd likely has led to increased antiracism efforts in medicine and beyond. This study provides valuable baseline data for comparison in future studies.

This survey study confirms that diversity is an area of interest for many family medicine program directors. Although the majority of programs (56%) represented in the survey results have initiatives in place to address diversity and inclusion in the workforce, the depth and quality of these initiatives was not assessed, and disappointingly, 44% of programs reported no initiatives. Programs with non-White program directors have a higher percentage of URM residents. Strong diverse program leadership is an important component to increasing the numbers of URM family physicians. However, increasing the numbers of URM family physicians, though important, is not enough. Qualitative research attending to the voices of URM residents, faculty, and staff might help clarify the steps necessary to develop long-term sustainable interventions to address discrimination and foster a climate that promotes diversity throughout the training environment.

References

- Census Bureau data (2017 1-Year Public Use Microdata Sample). DataUSA. Accessed November 24, 2019. https://datausa.io/profile/soc/physicians-surgeons#about

- Functions and Structure of a Medical School Standards for Accreditation of Medical Education Programs Leading to the MD Degree. Standard MS-8: Element 3.3. Liason Committee on Medical Education. March 2019. Accessed November 24, 2019. https://lcme.org/publications/

- ACGME Common Program Requirements (Residency). Requirement V.C.1.c).(5).(c) Accreditation Council of Graduate Medical Education. Accessed November 24, 2019. https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRResidency2019.pdf

- Lett LA, Orji WU, Sebro R. Declining racial and ethnic representation in clinical academic medicine: A longitudinal study of 16 US medical specialties. PLoS One. 2018;13(11):e0207274. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0207274

- Xierali IM, Hughes LS, Nivet MA, Bazemore AW. Family medicine residents: increasingly diverse, but lagging behind underrepresented minority population trends. Am Fam Physician. 2014;90(2):80-81.

- Terlizzi EP, Connor EM, Zelaya CE, Ji AM, Bakos AD. Reported importance and access to health care providers who understand or share cultural characteristics with their patients among adults, by race and ethnicity. National Health Statistics Reports; no 130. Hyattsville, MD: National Center for Health Statistics; 2019.

- Sabin JA, Rivara FP, Greenwald AG. Physician implicit attitudes and stereotypes about race and quality of medical care. Med Care. 2008;46(7):678-685. doi:10.1097/MLR.0b013e3181653d58

- Kington R, Tisnado D, Carlisle DM. Increasing racial and ethnic diversity among physicians: an intervention to address health disparities? In: Smedley BD, Stith AY, Colburn L, Evans CH, eds. The Right Thing to Do, The Smart Thing to Do: Enhancing Diversity in the Health Professions. Washington, DC: National Academy Press; 2001.

- Wheeler M, de Bourmont S, Paul-Emile K, et al. Physician and trainee experiences with patient bias. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1678-1685. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4122

- Premkumar A, Whetstone S, Jackson AV. Beyond silence and inaction: changing the response to experiences of racism in the health care workforce. Obstet Gynecol. 2018;132(4):820-827. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000002868

- Osseo-Asare A, Balasuriya L, Huot SJ, et al. Minority resident physicians’ views on the role of race/ethnicity in their training experiences in the workplace. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1(5):e182723. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.2723

- Fnais N, Soobiah C, Chen MH, et al. Harassment and discrimination in medical training. Acad Med. 2014;89(5):817-827. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000200

- Whitgob EE, Blankenburg RL, Bogetz AL. The discriminatory patient and family: strategies to address discrimination towards trainees. Acad Med 2016;91(11 Association of American Medical Colleges Learn Serve Lead: Proceedings of the 55th Annual Research in Medical Education Sessions):S64-S69. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0000000000001357.

- Wheeler M, de Bourmont S, Paul-Emile K, et al. Physician and trainee experiences with patient bias. JAMA Intern Med. 2019;179(12):1678-1685. doi:10.1001/jamainternmed.2019.4122

- Peterson NB, Friedman RH, Ash AS, Franco S, Carr PL. Faculty self-reported experience with racial and ethnic discrimination in academic medicine. J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(3):259-265. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.20409.x

- Edgoose JYC, Quiogue M, Sidhar K. How to identify, understand, and unlearn implicit bias in patient care. Fam Pract Manag. 2019;26(4):29-33.

- Simone K, Ahmed RA, Konkin J, Campbell S, Hartling L, Oswald AE. What are the features of targeted or system-wide initiatives that affect diversity in health professions trainees? A BEME systematic review: BEME Guide No. 50. Med Teach. 2018;40(8):762-780. doi:10.1080/0142159X.2018.1473562

- Aibana O, Swails JL, Flores RJ, Love L. Bridging the gap: holistic review to increase diversity in graduate medical education. Acad Med. 2019;94(8):1137-1141. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002779

- Aarons CB. Shaking up residency program admissions. AAMC Insights. May 14, 2019. Accessed September 21, 2020. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights/insights/shaking-residency-program-admissions

- Wusu MH, Tepperberg S, Weinberg JM, Saper RB. Matching our mission: a strategic plan to create a diverse family medicine residency. Fam Med. 2019;51(1):31-36. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.955445

- Pierre JM, Mahr F, Carter A, Madaan V. Underrepresented in medicine recruitment: rationale, challenges, and strategies for increasing diversity in psychiatry residency programs. Acad Psychiatry. 2017;41(2):226-232. doi:10.1007/s40596-016-0499-x

- Tunson J, Boatright D, Oberfoell S, et al. Increasing resident diversity in an emergency medicine residency orogram: a pilot intervention with three principal strategies. Acad Med. 2016;91(7):958-961. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000957

- Okike K, Phillips DP, Johnson WA, O’Connor MI. Orthopaedic faculty and resident racial/ethnic diversity is associated with the orthopaedic application rate among underrepresented minority medical students. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(6):241-247. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00076

- Shantharam G, Tran T, McGee H, Thavaseelan S. Examining trends in underrepresented minorities in urology residency. J Urol. 2018;199(4)(suppl):e595. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2018.02.1437

- Obeid S, Fanning A, Hultman CS. Diversity and inclusion in plastic surgery education: a national survey by the American Council of Academic Plastic Surgeons, Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. Global Open: 2017; 5(9S-2): e1469.

- Lane-Fall MB, Miano TA, Aysola J, Augoustides JGT. Diversity in the emerging critical care workforce: analysis of demographic trends in critical care fellows from 2004 to 2014. Crit Care Med. 2017;45(5):822-827. doi:10.1097/CCM.0000000000002322

- Guh J, Harris CR, Martinez P, Chen FM, Gianutsos LP. Antiracism in residency: a multimethod intervention to increase racial diversity in a community-based residency program. Fam Med. 2019;51(1):37-40. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.987621

- Mainous AG III, Seehusen D, Shokar N. CAFM Educational Research Alliance (CERA) 2011 Residency Director survey: background, methods, and respondent characteristics. Fam Med. 2012;44(10):691-693.

There are no comments for this article.