Background and Objectives: A patient’s wait to see a provider before scheduled appointments may impact their experience at the primary care clinic. This survey study examined how long patients are willing to wait, where they prefer to wait, and whether punctual care in the clinic may be more prioritized than quality care.

Methods: We disseminated a survey in the waiting room of an urban adult primary care office to assess patient perceptions and evaluate the importance of punctuality. We completed subgroup analyses to examine any differences by age and gender in patient expectations and values.

Results: The survey was completed by 180 respondents (92% response rate). Patients report they can wait up to 20 minutes (95% CI 19.1-22.0) before seeing their provider. A subgroup analysis determined that age alone cannot be used as a screening tool to identify patients who require the most punctual care. Women expressed a more explicit preference for quality rather than punctuality compared to men (P=.0017).

Conclusions: Results suggest that patients are unwilling to forego quality care for punctuality alone. Our findings may help providers better understand patient perceptions of waiting at a primary care clinic.

The patient’s wait to see a provider before a scheduled appointment has been shown to be one of the largest sources of discontent during the clinical encounter.1-3 Patient satisfaction is an important outcome of health care services and can affect compliance with medical advice, service utilization, and the clinician-patient relationship.4-7 Patient satisfaction can lead to improved health outcomes, reduced mortality through behavior changes, and better treatment adherence.8-10 Therefore, wait times are indeed a component of patient satisfaction, but also an important feature of quality care.

As patient satisfaction continues to play a growing role during the clinical visit, a more detailed understanding of patient expectations and preferences should be critically examined. Many studies have demonstrated the clear inverse relationship between wait time and patient satisfaction,11-14 but few studies have examined how long patients are willing to wait and if they ever value punctuality more than quality. There is a paucity of research available that describes the patient’s expectation to wait. The purpose of this study was to examine the patient perceptions of wait time by disseminating a survey in the waiting room of a single adult primary care office.

We invited all patients in the waiting room of a single adult primary care office in Quincy, Massachusetts, to complete a survey. Survey collection took place every Monday from 1 pm to 3 pm between August 2019 and December 2019 in attempt to maintain consistency and reduce possible confounding variability. The adult primary care office included three physicians and was located in an urban community that served patients with private insurance, Medicare, and Medicaid. The research staff approached all patients in the waiting room and administered a paper survey for patients who consented to participate. Patients were asked to submit their responses in a drop-off container when they completed the survey to reduce the possibility of participation bias. Our university’s institutional review board considered this study exempt from review because it did not involve patient identifying information.

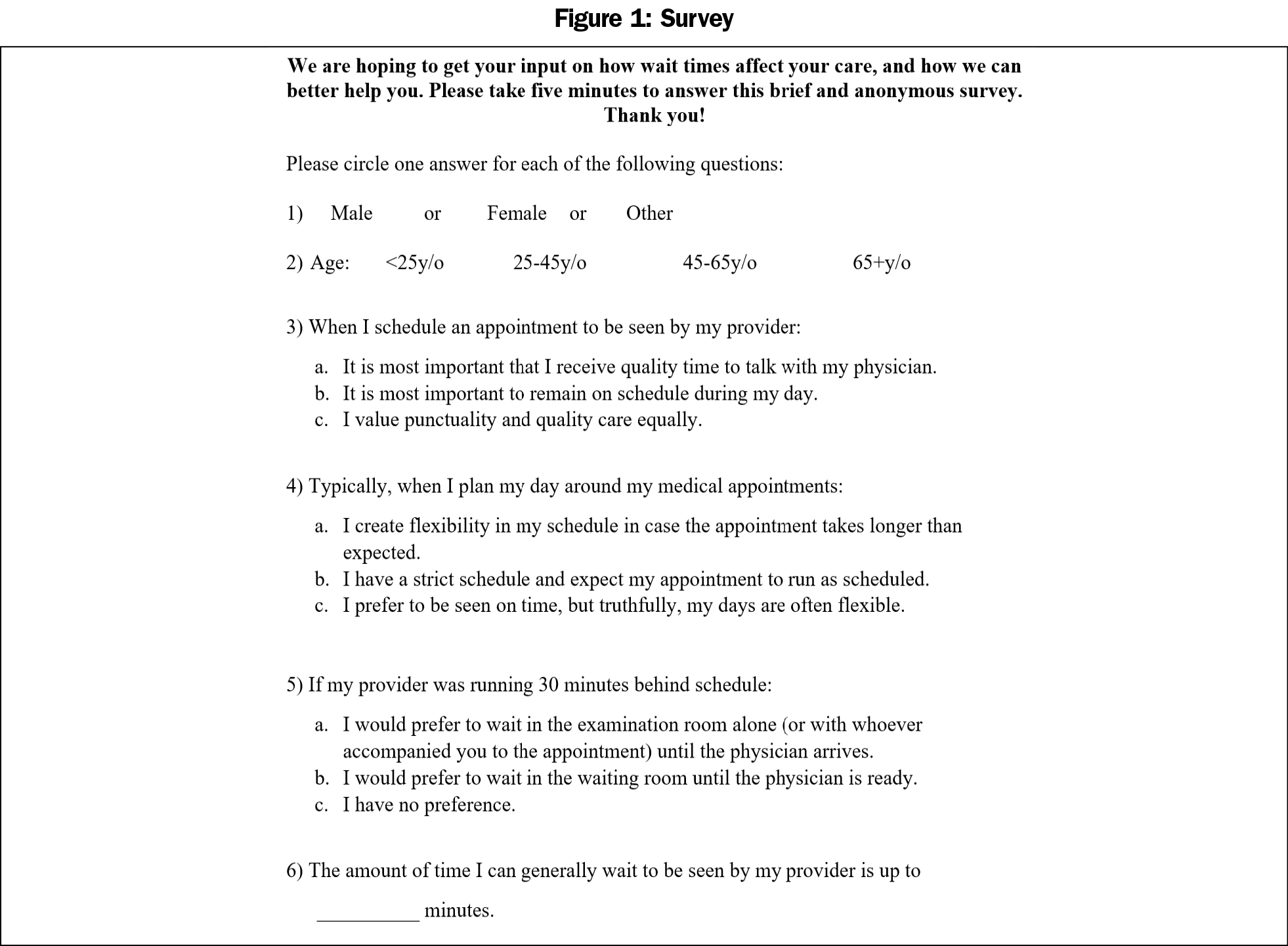

We designed survey questions to examine current perceptions of wait time at a primary care clinic. No survey has been previously validated to measure patient perceptions and expectations of wait time. Five random patients initially reviewed our survey to improve reliability and validity. This pilot cohort was cognitively interviewed to provide feedback on the survey.15 This initial cohort all reported the survey to be straightforward and appropriate.

Patients were asked to provide their age and gender to collate demographic information. The survey included four questions to measure the perceptions of waiting, including priorities, preferences, and an estimate of a reasonable wait time (Figure 1).

We performed a statistical analysis using Excel version 15.40 software (Microsoft Corp, Redmond, WA). We performed a subgroup analysis comparing male and female responses using a two-tailed populational proportion test and a Mann-Whitney U test. We conducted additional subgroup analysis comparing age groups using a Fischer Exact Test and an analysis of variance test.

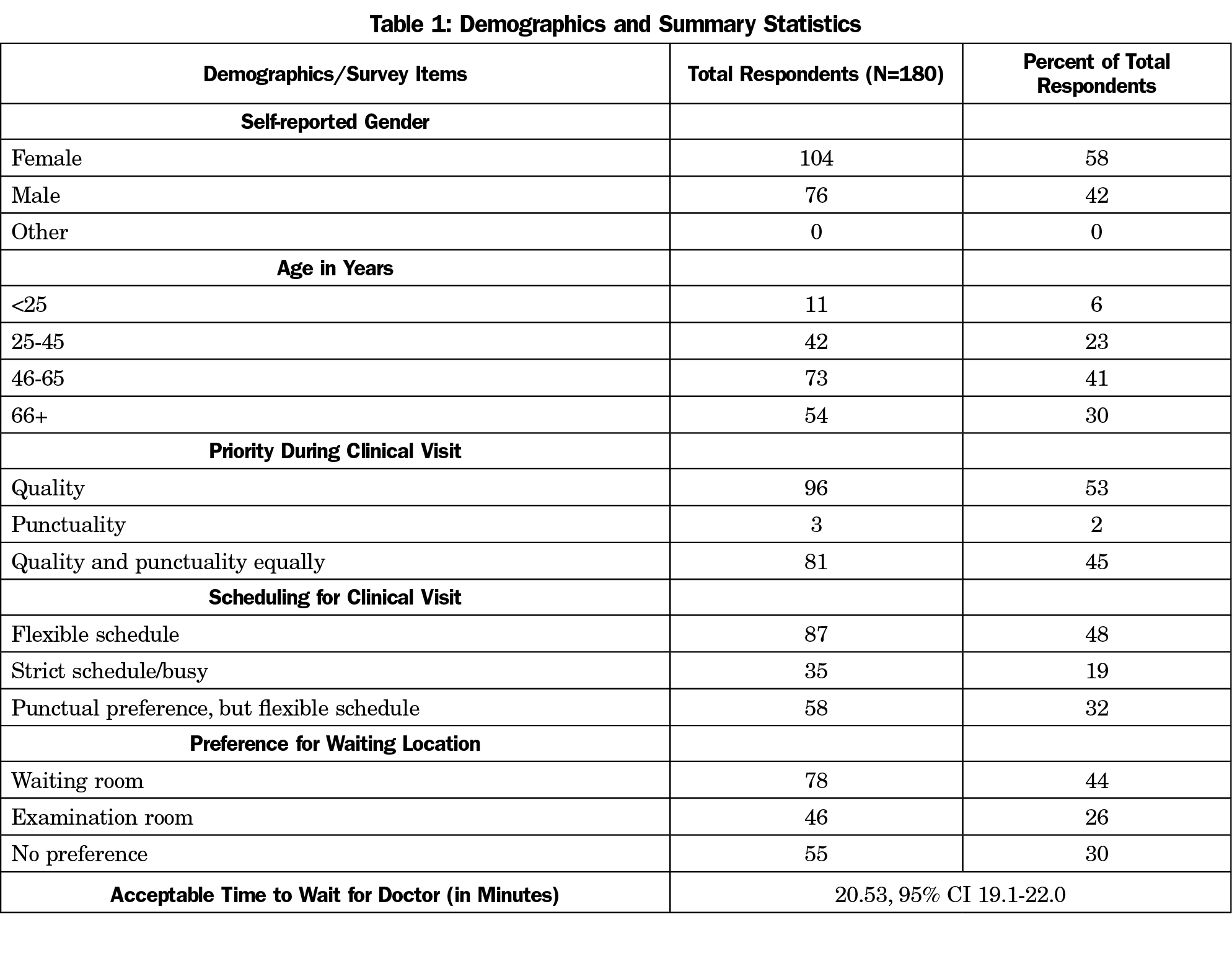

One hundred ninety-six patients were approached in the waiting room, of which 180 agreed to complete the survey (92% response rate). Characteristics of the study sample and summary statistics are presented in Table 1. Only 2% of respondents expressed an explicit priority to “remain on schedule during my day,” compared to 53% of respondents who marked quality care as the single-most important priority. Eighty percent of respondents revealed they had flexible schedules, although 32% of those respondents noted they still prefer punctuality when possible. Forty-four percent of respondents answered a preference to wait in the waiting room, and 30% marked they had no preference. Patients reported they can generally wait up to 20.53 minutes (95% CI 19.1-22.0) before seeing their provider.

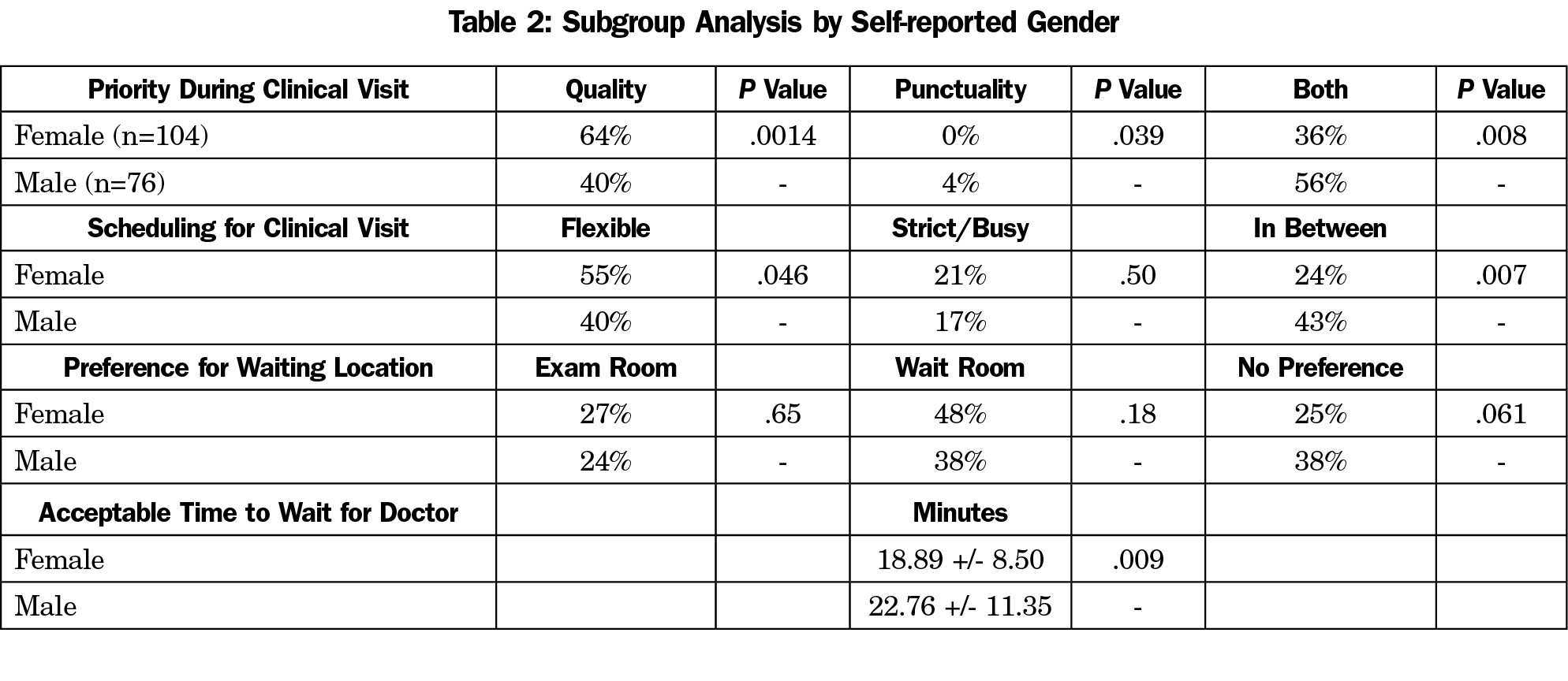

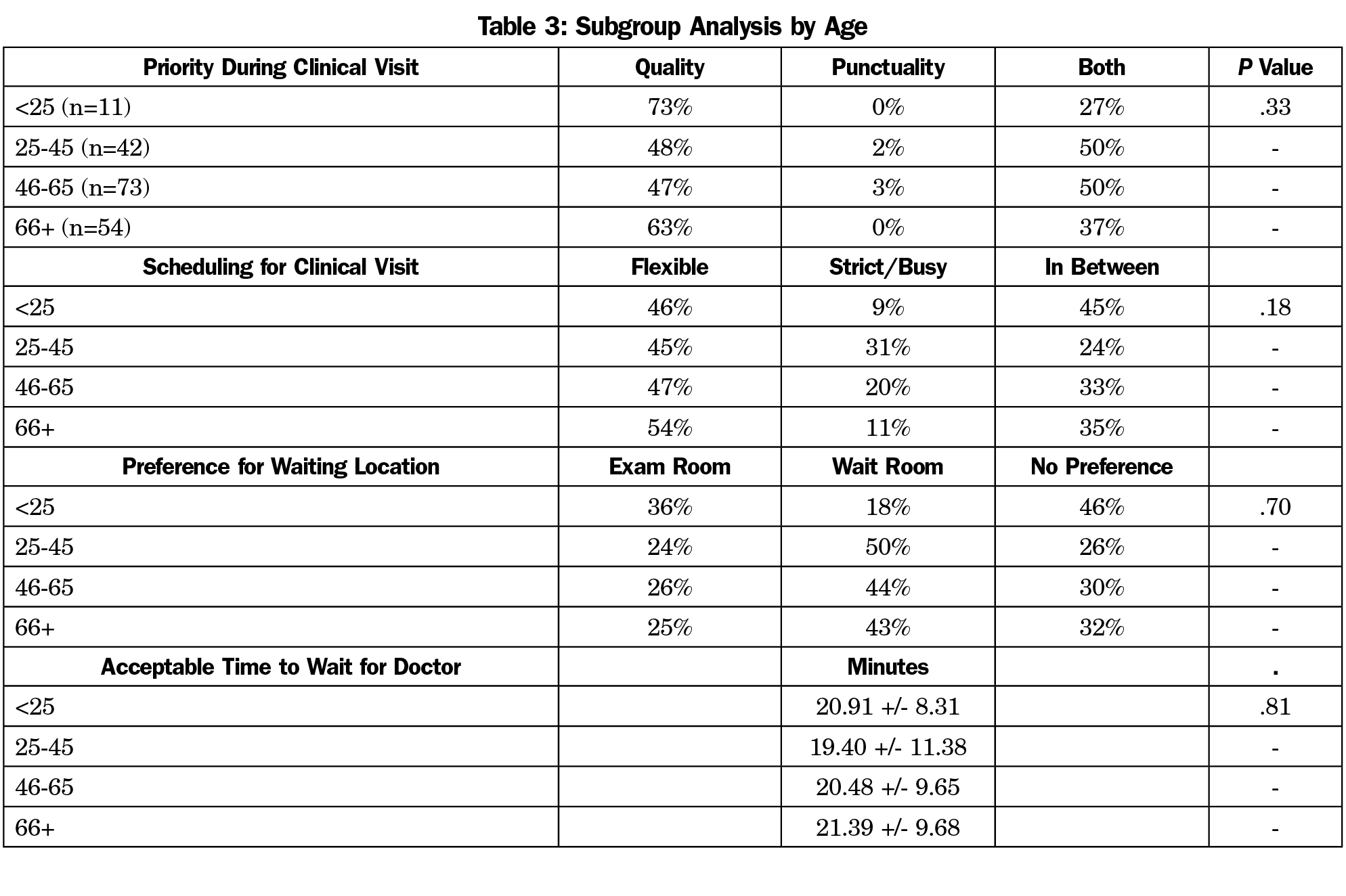

We conducted a subgroup analysis to examine any major differences in preferences and values between gender (Table 2) and age (Table 3); 64% of women noted they prioritized quality compared to 40% of men (P=.0017). Likewise, 4% of men noted they prioritize punctuality compared to quality at their visits, while no women selected that answer choice (P=.039). A subgroup analysis by age groups found no significant differences.

This study builds on previous literature by finding that patients arrive to the clinic with an expectation to wait up to 20 minutes (95% CI 19.1-22.0) and that patients are almost entirely unwilling to sacrifice quality care for punctuality alone. Providers may be able to leverage this expectation and create flexibility within their schedule to accommodate different patient needs. A significant proportion of patients (nearly one in five) self-identify as having inflexible schedules. Practices should strive to identify these patients to enhance satisfaction and care goals. Interestingly, patients aged 25 to 45 years do not report more inflexible schedules compared to other age groups. Therefore, age alone cannot be used as a screening tool to identify patients who require the most punctual care. Practices should not assume that older patients are more amenable to longer waits due to more flexible schedules. Older patients may experience more barriers to care compared to younger patients, such as scheduling multiple appointments on the same day or reliance on transportation.

Future research should continue to explore how practices can reduce wait time burden and customize the clinical experience based on patient preferences. Strategies including self-rooming, physician block scheduling, and workspace redesign have demonstrated improved patient satisfaction.16-18 As more clinics begin to offer Telemedicine appointments, particularly in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, wait time may have less of an impact on satisfaction than previously reported, since patients can continue their normal routine at home or work while waiting. Future research could adapt this survey for virtual patients and reexamine the perceptions of punctuality and quality during virtual appointments.

The generalizability of the findings may be limited because the study was conducted at a single site. Patients completed the survey at different time points of their wait. It is possible that patients who completed the survey after waiting extensively, or after immediately arriving to the clinic, could have variable reflections about wait time. Patients only reflected on their preferences before the clinical visit. It is possible that patients could disclose different priorities after the visit.

Data gathered from this survey study of patients at an adult primary care clinic provide important information regarding perceptions of wait time. Providers can leverage patient expectations to enhance satisfaction.

References

- Bleustein C, Rothschild DB, Valen A, Valatis E, Schweitzer L, Jones R. Wait times, patient satisfaction scores, and the perception of care. Am J Manag Care. 2014;20(5):393-400.

- Braddock CH III, Snyder L. The doctor will see you shortly. The ethical significance of time for the patient-physician relationship. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(11):1057-1062. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.00217.x

- Michael M, Schaffer SD, Egan PL, Little BB, Pritchard PS. Improving wait times and patient satisfaction in primary care. J Healthc Qual. 2013;35(2):50-59. doi:10.1111/jhq.12004

- Kahan B, Goodstadt M. Continuous quality improvement and health promotion: can CQI lead to better outcomes? Health Promot Int. 1999;14(1):83-91. doi:10.1093/heapro/14.1.83

- Hjortdahl P, Laerum E. Continuity of care in general practice: effect on patient satisfaction. BMJ. 1992;304(6837):1287-1290. doi:10.1136/bmj.304.6837.1287

- Swenson SL, Buell S, Zettler P, White M, Ruston DC, Lo B. Patient-centered communication: do patients really prefer it? J Gen Intern Med. 2004;19(11):1069-1079. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2004.30384.x

- Zandbelt LC, Smets EM, Oort FJ, Godfried MH, de Haes HC. Medical specialists’ patient-centered communication and patient-reported outcomes. Med Care. 2007;45(4):330-339. doi:10.1097/01.mlr.0000250482.07970.5f

- Jha AK, Orav EJ, Zheng J, Epstein AM. Patients’ perception of hospital care in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2008;359(18):1921-1931. doi:10.1056/NEJMsa0804116

- Lyu H, Wick EC, Housman M, Freischlag JA, Makary MA. Patient satisfaction as a possible indicator of quality surgical care. JAMA Surg. 2013;148(4):362-367. doi:10.1001/2013.jamasurg.270

- Glickman SW, Boulding W, Manary M, et al. Patient satisfaction and its relationship with clinical quality and inpatient mortality in acute myocardial infarction. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2010;3(2):188-195. doi:10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.109.900597

- Howard M, Agarwal G, Hilts L. Patient satisfaction with access in two interprofessional academic family medicine clinics. Fam Pract. 2009;26(5):407-412. doi:10.1093/fampra/cmp049

- Leddy KM, Kaldenberg DO, Becker BW. Timeliness in ambulatory care treatment. An examination of patient satisfaction and wait times in medical practices and outpatient test and treatment facilities. J Ambul Care Manage. 2003;26(2):138-149. doi:10.1097/00004479-200304000-00006

- Anderson RT, Camacho FT, Balkrishnan R. Willing to wait?: the influence of patient wait time on satisfaction with primary care. BMC Health Serv Res. 2007;7(1):31. doi:10.1186/1472-6963-7-31

- Camacho F, Anderson R, Safrit A, Jones AS, Hoffmann P. The relationship between patient’s perceived waiting time and office-based practice satisfaction. N C Med J. 2006;67(6):409-413. doi:10.18043/ncm.67.6.409

- Willis GB, Artino AR Jr. What do our respondents think we’re asking? Using cognitive interviewing to improve medical education surveys. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5(3):353-356. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-13-00154.1

- Koonce T, Neutze D. Improving patient care through workspace renovation and redesign: A lean approach. Fam Med. 2020;52(6):435-439. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.429243

- Murray M, Berwick DM. Advanced access: reducing waiting and delays in primary care. JAMA. 2003;289(8):1035-1040. doi:10.1001/jama.289.8.1035

- Kamnetz S, Marquez B, Aeschlimann R, Pandhi N. Are waiting rooms passé? A pilot study of patient self-rooming. J Ambul Care Manage. 2015;38(1):25-28. doi:10.1097/JAC.0000000000000045

There are no comments for this article.