Ryuichi Ohta, MD, MHPE, et al identified the challenges in family medicine training in rural Japan.1 According to the study, family medicine residents struggled to adapt to a broader practice range than those taught in medical school. Additionally, we have found that another issue related to their training in Japan exists. Current family medicine residency programs in Japan provide pediatric training in inpatient settings similar to pediatric residency training. The family medicine residents must rotate in pediatrics for 3 months to obtain their specialty board certification from the Japan Primary Care Association (JPCA), but no specific outpatient training frequency has been set.2

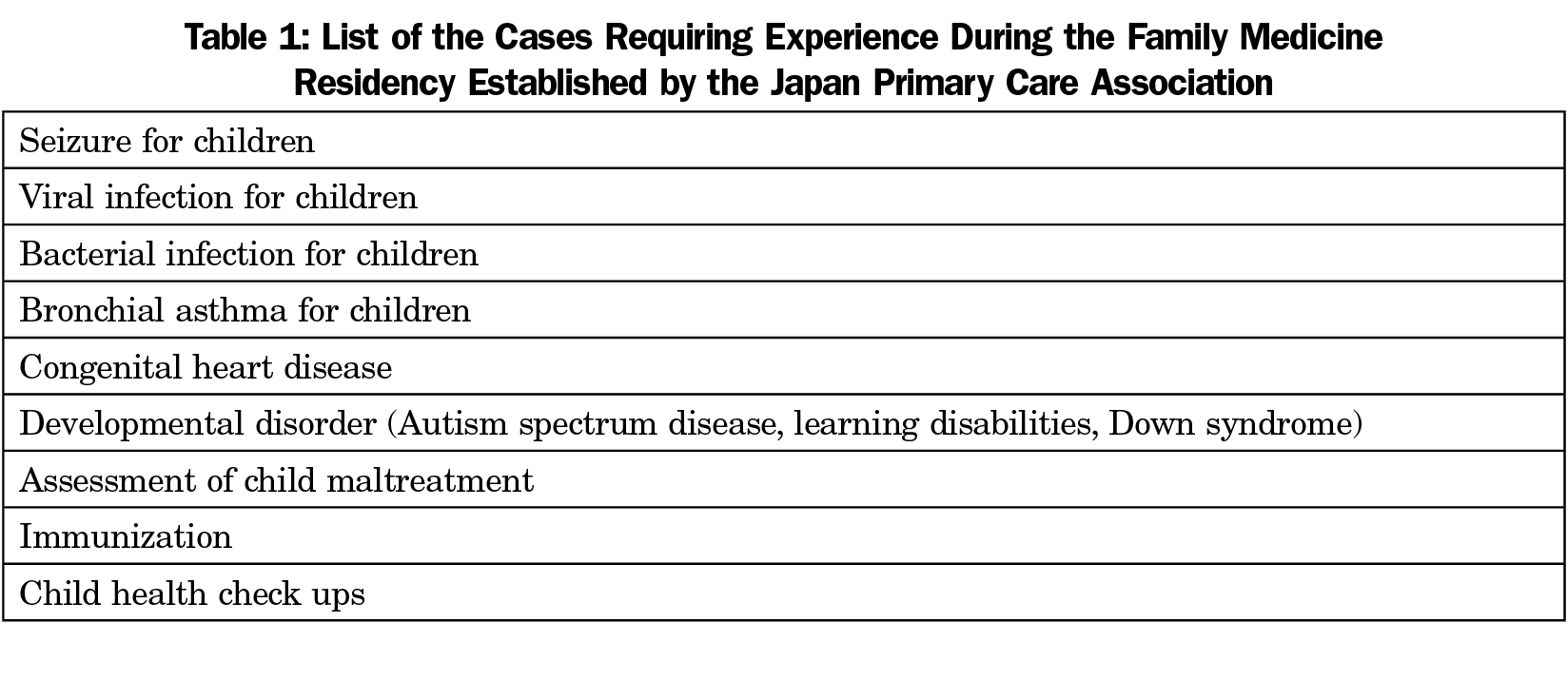

In the United Kingdom, Canada, and the United States, pediatric training within family medicine residencies had been mainly inpatient hospital-based. However, previous reports have recommended either a 6-month inpatient hospital-based training or a 4-week outpatient-based training to experience sufficient outpatient pediatric cases.3 The current training program in Japan may not provide adequate opportunities for the residents due to the short training periods and decreased outpatient visits due to declining birth rates and improved immunization. As a result, they may not experience the required cases during the family medicine residency set forth by the JPCA (Table 1).2

Our facility is one of Japan’s largest and oldest family medicine training facilities for future solo family practitioners on isolated islands.4 The training program graduates need to cover all island inhabitants’ health problems, including children. To determine whether our pediatric training was valuable to actual family practice, we conducted a paper-based questionnaire survey between November 2017 and February 2018, to 15 island physicians, who graduated from our program. We accepted responses received by March 20, 2018. We analyzed these without identifying the person and the clinic. The questionnaire covered their training periods including numbers and kinds of cases they encountered, and the participants selected their answers from multiple lists. This study was approved by our institutional ethics review board.

Twelve of 15 responses were returned (80%). The results showed that the varieties and number of cases they experienced during the 3-month inpatient hospital-based training varied by rotation season (more cases in the winter season and fewer cases in the summer season). Furthermore, they reported minimal experience with the following types of cases: child maltreatment, obesity, autism spectrum disease, health check-ups, adolescent patient care, and immunizations. These cases are expected in outpatient clinics. However, in the context of inpatient-based training, they did not gain enough experience against the requirement by the JPCA.

Ohta et al revealed three main themes (educational background, changing environment, driving the learning cycle) and their concepts were effective for the residency education. We are currently planning a multicenter study in Japan to clarify the current pediatric training programs for family medicine residents. After that, we hope to contribute to the development of an ideal pediatric training program for future family medicine practice by incorporating educational concepts suitable for Japanese family medicine residents, as Ohta et al reported.