Background and Objectives: Transgender persons face many barriers to accessing health care, including identifying a knowledgeable physician. Medical schools have made curricular changes addressing cultural competence in transgender medicine, but changes are inadequate to graduate physicians competent in gender-affirming health care. The aim of this study was to assess the current state of education on the comprehensive health care of transgender patients, including gender-affirming health care (GAH) strategies (hormone therapy, surgical interventions) in US and Canadian family medicine clerkships (FM clerkships) in addition to the beliefs and actions of the directors making those curricular decisions.

Methods: Questions regarding transgender education within FM clerkships were included in the 2018 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine clerkship directors. The online survey was distributed via email invitation to 128 US and 16 Canadian FM clerkship directors between June 21, 2018 and August 4, 2018.

Results: Seventy-two percent (68/94) of FM clerkship directors agreed transgender health care should be a required part of the medical school curriculum. Sixty-six percent report active advocacy within their institutions for increased curricular time devoted to transgender health care. Fifty-six percent (53/94) treat transgender patients in their own clinical practice, but just 26% agreed they were comfortable teaching transgender health care to medicals students. While the presence of transgender patients within the clinical practice did not have a significant impact on FM clerkship directors’ comfort teaching this subject, having transgender friends or acquaintances did.

Conclusions: FM clerkships are primed for inclusion of comprehensive transgender and GAH education in their curriculum. Increasing comfort of FM clerkship directors in teaching this subject area by providing accessible curriculum may encourage further uptake of this content into FM clerkships.

Conservative estimates report 0.3% of the total US population is transgender, representing 1 million individuals.1-3 Transgender persons face many barriers to accessing care, but the most commonly cited is difficulty finding a knowledgeable health care provider.1,4,5 A 2010 study of physicians found that 40% of respondents had no training on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer (LGBTQ) care in medical school or residency. The majority of those with education in LGBTQ care reported it was “not very” or “not at all” useful. Most physicians agreed that further training and education in the area of comprehensive transgender and gender-affirming health care (GAH) is necessary.6

While many medical schools have attempted to address the lack of LGBTQ knowledge prevalent in the health care community through increasing teaching in tolerance and cultural competency, that training alone is inadequate to graduate physicians knowledgeable in the necessary preventive and appropriate GAH (hormone therapy, surgical interventions) of transgender and gender-diverse persons.1 Schools with LGBTQ curricula reported a median of 5 hours of content within the 4-year curriculum, compared to an average of 3 hours 26 minutes in a 1992 study.4,7 A 2011 survey of US medical schools reported one-third of schools taught zero hours of LGBTQ-specific curriculum in the clinical years. In a 2015 survey of all Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME)-accredited US faculty practices, with a 50% response rate, only 16% of institutions reported having comprehensive LGBTQ training programs and 52% reported having no LGBTQ curriculum. Eighty percent of the respondents expressed interest in doing more to address these issues.4,7 A recent survey of Canadian pediatric residency programs confirms the need for further comprehensive transgender and GAH education with less than 50% of residents citing comfort in specific areas of transgender care and 90% stating further education on gender diversity is required.8

Many barriers to increased LGBTQ curricula have been cited. These barriers include an absence of trained faculty, faculty perception that LGBTQ health care is not relevant to their specific curricular content, and a lack of faculty and attending physician role models with whom students can discuss issues of sexual orientation, attraction, or gender identity.7 In the Canadian survey of pediatric programs cited above, pediatric program directors most frequently cited finding time in an already busy curriculum as a barrier to inclusion of gender diversity training.8 However, evidence suggests that even small increases in transgender education increase medical students’ and other provider’s knowledge, attitudes, and comfort in treating future LGBTQ patients.9 In one study of second-year medical students, a single didactic session about gender identity, classic treatment regimens and monitoring requirements with additional small group discussion and subsequent testing of the material, was added into the required second-year endocrinology course. Authors noted a 59% drop in students’ anticipated discomfort when caring for transgender patients.10 A second study of a 1-hour didactic session provided to faculty, medical students, and residents at a single institution showed improved attitudes, knowledge, and comfort in caring for transgender individuals.11

While medical schools have begun educating medical students both in culturally competent and medically comprehensive GAH of transgender patients, barriers remain to universally adopting this curricular change. FM clerkship directors charged with implementing clinical curriculum play a key role in making future changes. The aim of this study was to assess the current state of education on the comprehensive health care of transgender patients, including GAH, in North American FM clerkships, in addition to the beliefs and actions of the directors making those curricular decisions.

Data were gathered and analyzed as part of the 2018 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine clerkship directors. CAFM is a joint initiative of four major academic family medicine organizations, including the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine, the North American Primary Care Research Group, the Association of Departments of Family Medicine and the Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors. The cross-sectional survey of clerkship directors is distributed annually to the institutional representatives of qualifying medical schools. The institutional representative is the clerkship director at the main campus of the school or their designee. Qualifying medical schools are accredited by LCME or Committee on Accreditation of Canadian Medical Schools (CACMS) and are located within the United States and Canada. To qualify, the school must have students who complete a family medicine clerkship or a primary care clerkship requiring a family medicine component with oversight by a family medicine educator. In 2018, 128 US and 16 Canadian unique individuals identified as family medicine educators directing a family medicine or primary care clerkship.

CAFM members were invited to propose survey questions for inclusion in the CERA survey. A CERA research mentor was assigned to approved projects to help refine questions that were finalized following pilot testing.

The survey, conducted through the online program SurveyMonkey, was distributed via email invitation to 128 US and 16 Canadian family medicine clerkship directors between June 21, 2018 and August 4, 2018. Invitations to participate in the study included a personalized greeting and letter containing a link to the survey signed by the president of each of the four sponsoring organizations. During the course of the survey, the survey director identified 15 changes in clerkship directors, 13 via direct contact from the prior director, and 2 indicated in survey responses. All newly identified clerkship directors were invited to participate in the survey. Additionally, clerkship directors were contacted by personal email to verify their status as clerkship directors, to check accuracy of email addresses, and to encourage participation. Nonrespondents received five weekly requests, plus one final request 2 days before closing the survey. The American Academy of Family Physicians’ Institutional Review Board approved the study in June 2018. Development of transgender-specific survey questions was guided by extensive review of available literature regarding known barriers to transgender persons seeking health care, including physician bias toward and discomfort with this particular patient population.2-6,12-17 Additional questions highlighted common medical education resources that could be useful for implementation of a new curriculum. The survey utilized both dichotomous and interval questions. We used a Likert scale of 1-5 to measure responses, with 1 being extremely likely and 5 being extremely unlikely. Lower responses indicated a higher value of transgender information and education. The 12-question survey was estimated to take less than 5 minutes to complete (Figure 1).

Statistical Analysis

We used nonparametric statistical measures to compare positive interest in education and implementation of transgender conditions and health care, respectively, compared to negative/no interest. We determined descriptive statistics on all variables including frequencies and percentages, means and standard deviations, or medians and interquartile ranges, where appropriate. To examine the association of various clerkship director demographics or program characteristics with current transgender curriculum in the family medicine clerkship, we used χ2 or two-sample t tests. To examine the association of various clerkship beliefs with likelihood of transgender education implementation or agreement with teaching and access to transgender education, we used Kruskal-Wallis nonparametric tests. For the Kruskal-Wallis tests, we used the Dwass-Steel-Critchlow-Fligner multiple comparison test to adjust the overall α level for post hoc pair-wise differences. We assessed all P values using an a level of 0.05. We performed all analyses using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, North Carolina).

Of 144 FM clerkship directors, 99 (69%) responded to the CERA survey. Ninety percent of respondents were from schools in the United States. Respondents—62 females and 32 males—indicated serving as clerkship directors for 0-20 years, with a mean of 5 years (Table 1). Ninety four of 144 directors (65%) responded to at least some of the transgender survey questions. Of those who did not answer, all represent medical schools in the United States, four public and one private. Additional demographic data is available on three of the directors, all of whom were non-Hispanic White. Four indicated the length of time they had served as clerkship directors, ranging from 3-12 years.

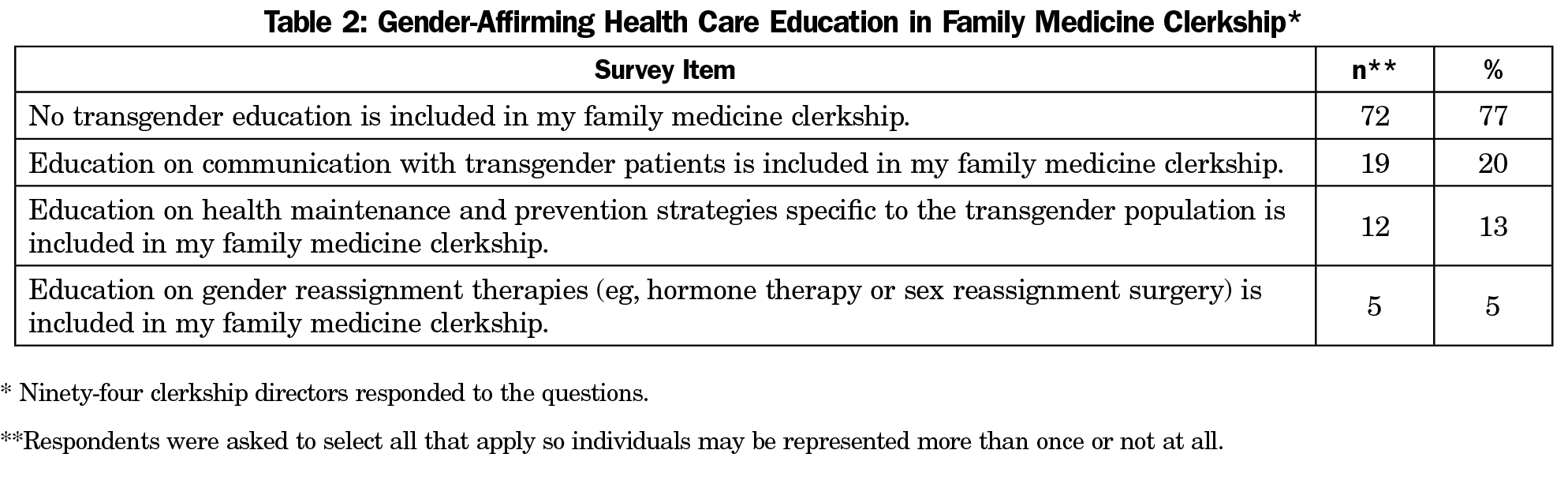

Seventy-seven percent of respondents indicated that no transgender health care education was currently included in their clerkships (72/94). Twenty-percent indicated inclusion of transgender-specific communication (19/94), 12% health care maintenance and preventive care in the transgender population (13/94), and 5% GAH (5/94; Table 2).

Analysis of the demographic characteristics of responding clerkship directors and their representative schools found no significant differences between programs having no transgender education and those programs with education on communication with or the health maintenance and preventive care needs of transgender patients. Institutions that included education on GAH had FM clerkship directors with fewer years of experience (mean=2.0, SD=1.0) than institutions that did not (mean=6.3, SD=4.9, P<0.01; Table 2).

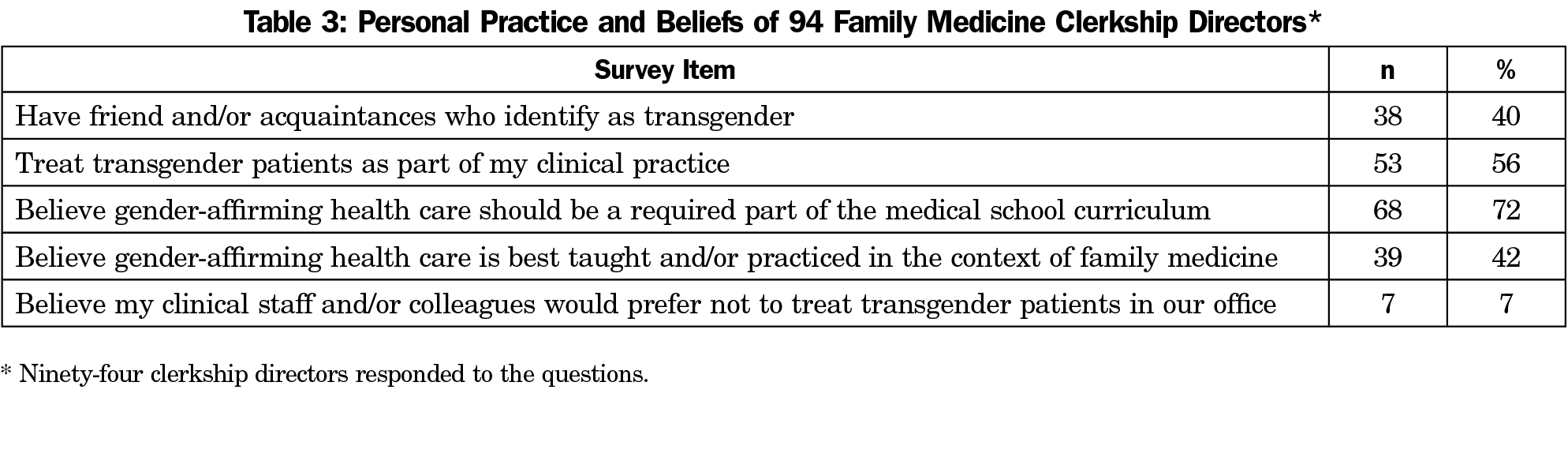

Seventy-two percent (68/94) of FM clerkship directors agreed that education regarding transgender healthcare should be a required part of the medical school curriculum, with 42% (39/94) agreeing this curriculum would be best taught in the context of family medicine. Fifty-six percent (53/94) of FM clerkship directors currently treat transgender patients in their own clinical practice, and just 7% (7/94) believe their clinical colleagues would prefer not to treat transgender patients (Table 3).

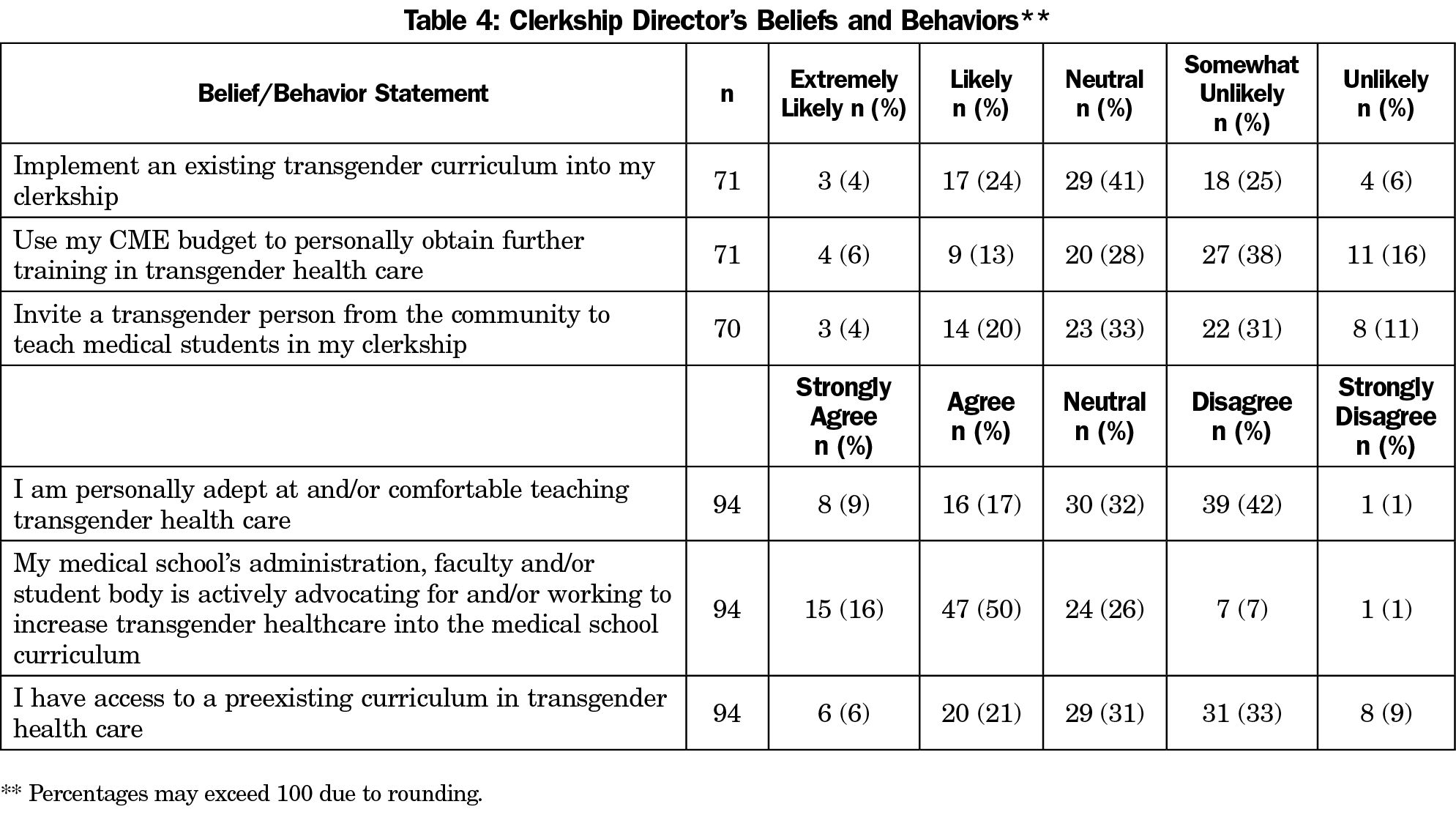

Twenty-six percent of FM clerkship directors strongly agreed or agreed they were personally comfortable teaching transgender health care, while 43% disagreed or strongly disagreed. Sixty-six percent strongly agreed or agreed there was active advocacy within their institutions for an increase in transgender-specific health care within the curriculum. Twenty-seven percent strongly agreed or agreed to having access to a preexisting curriculum in transgender health care, while 42% disagreed or strongly disagreed (Table 4).

Further analysis of FM clerkship directors and their representative schools found a significant difference by location influencing access to preexisting transgender educational materials. Clerkship directors located in Canada (median=4.0 interquartile range [IQR]=3-4) indicated significantly easier access to a preexisting transgender curriculum than US directors (median=3.0, IQR=2-3.5, P<.05). The 72 FM clerkship directors who indicated they did not currently include any transgender health care education in their clerkship (Table 2) were subsequently directed to and answered questions regarding their likelihood of use of available resources regarding transgender health care. Twenty-eight percent (20/71), 18% (13/71), and 24% (17/70) of FM clerkship directors, respectively, stated they were likely or extremely likely to implement an existing transgender curriculum, use their personal CME budget for transgender health care education, or invite a transgender person from their own community to teach medical students while 31% (22/71), 54% (38/71), and 43% (30/70), respectively, reported being somewhat unlikely or unlikely to do so (Table 4).

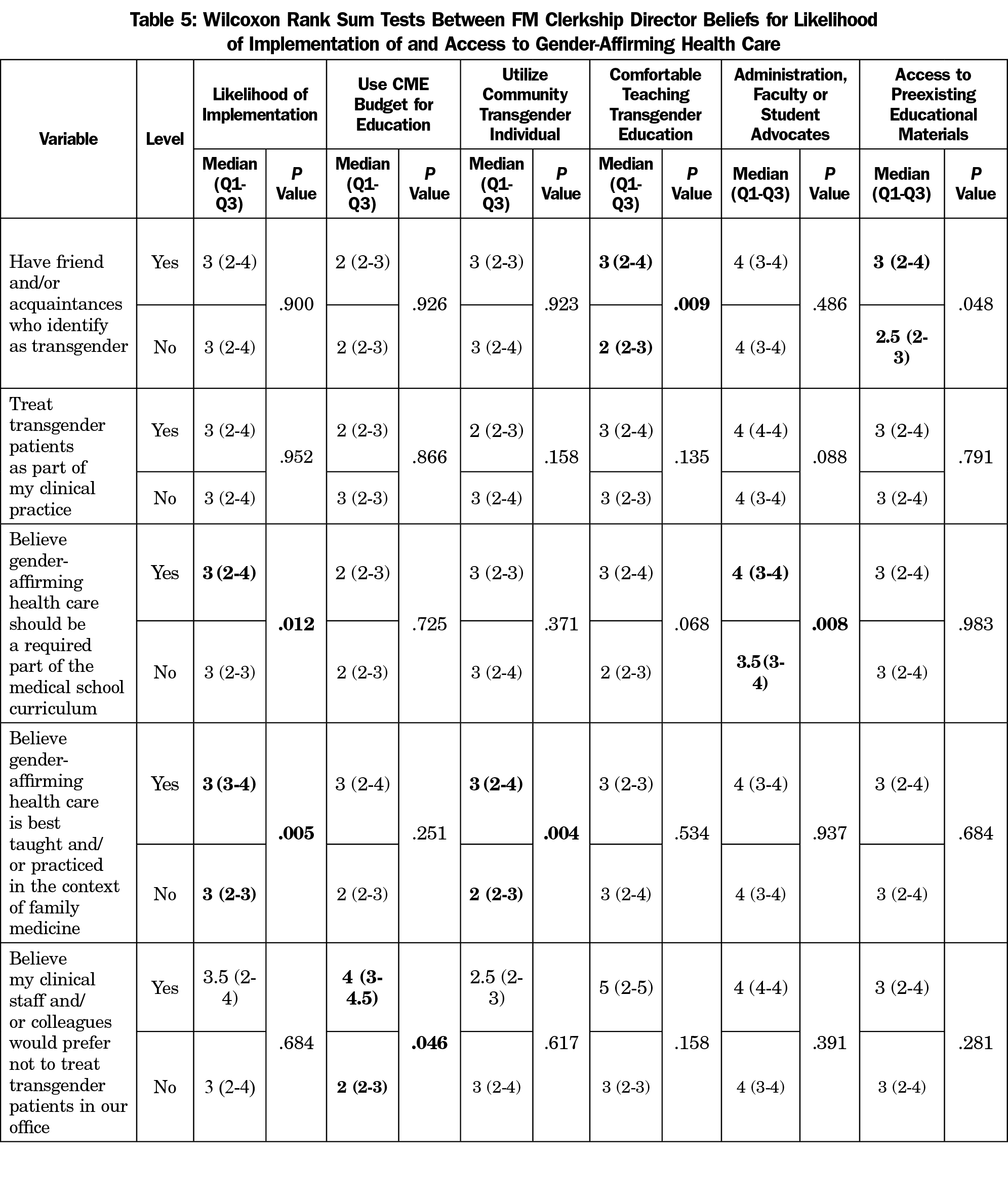

In analyzing how FM clerkship directors’ personal beliefs and practices may influence their professional beliefs and behaviors, several statistically significant relationships were identified. FM clerkship directors with transgender friends or acquaintances reported being more comfortable in teaching transgender education (P<.01) and more likely to have access to preexisting transgender education (P<.05). FM clerkship directors who currently believe transgender education should be a required part of medical school education had a higher likelihood of implementing an existing transgender curriculum into their clerkship (P<.05) and were more likely to indicate their medical school’s administration, faculty, and/or students were actively advocating for and/or working to increase transgender health care education into the medical school’s curriculum (P<.01). Those FM clerkship directors who believed transgender education was best taught in the context of family medicine indicated a significantly higher likelihood of implementing an existing transgender curriculum (P<.01) and inviting a transgender person from the community to teach medical students in their clerkship (P<.01). Finally, FM clerkship directors indicated a belief their clinical staff and/or colleagues would prefer not to treat transgender patients in their office had a significantly higher likelihood of using their CME budget to obtain training in transgender education (P<.05; Table 5).

It is evident transgender patients in our communities deserve better access to, and experiences with, health care systems. Encouragingly, our data indicate very low levels of perceived transphobia and high levels of care of transgender individuals within FM clerkship director practices. It is unknown whether clinical exposure to transgender patients alone is sufficient to affect overall belief systems and knowledge of comprehensive transgender and GAH in medical students. Our data indicate it does not substantially improve knowledge, with FM clerkship directors who treat transgender patients in their clinical practice not reporting any increased comfort in teaching transgender materials or having improved access to existing educational materials. However, FM clerkships should encourage students to gain a deeper understanding of patients, including their social contexts, in an effort to identify transgender individuals and form personal connections with those same individuals.

Interestingly, FM clerkship directors reporting these personal connections with transgender friends and/or acquaintances not only reported a greater level of comfort teaching about transgender health care, but also easier access to existing transgender health curricula. These differences suggest personal connections with transgender persons change belief systems or behavior, leading directors to seek out transgender curricula for their FM clerkships. This is in spite of the fact this group of FM clerkship directors did not have higher levels of administrative, faculty or student advocacy within their institutions for this curricular change.

Advocacy does matter, however, with more FM clerkship directors reporting a belief transgender and GAH should be a required part of the medical school curriculum also reporting more advocacy for such a curricular change within the institution. It is not surprising those holding this belief also report a higher likelihood of implementing an existing transgender curriculum into their clerkship. Continued efforts at designing accessible curricular materials for clerkship directors may help further efforts toward improving education in this domain.

One critical medical education issue to resolve is where the curricula for the clinical care of LGBTQ patients should be housed in order to ensure universal introduction on the care of this patient population to medical students. This d ilemma may account for the number of clerkship directors remaining neutral (41%) on the question addressing implementing a transgender curriculum. Knowledge that most FM clerkship directors actively care for transgender patients in their own clinical practice suggests many medical students have opportunities to interact with transgender patients during the course of their FM clerkship. Yet, interaction with transgender patients alone is not adequate for comprehensive GAH of this population. While it is important to be able to comfortably communicate with diverse populations, including transgender persons, their health care needs are sufficiently different from the general population as to require specific knowledge and skills. The knowledge and skills needed to provide basic GAH, such as hormone prescribing and management, are missing from nearly all family medicine clerkships.

Making curricula on GAH readily available to FM clerkship directors may improve the number of medical students graduating with a sufficient foundation of the knowledge and skills needed to comfortably care for transgender and gender diverse patients in residency and beyond. However, our results indicate that less than 30% of clerkship directors would be likely to implement an available curriculum in their clerkship. Active advocacy for inclusion of comprehensive transgender and GAH is necessary to encourage greater uptake of available curricula by FM clerkship directors given the number of competing educational topics vying for limited curricular time. Knowledge of the prevalence of practices caring for transgender patients may also convince FM clerkship directors, most of whom already believe transgender education is an important piece of medical school curricula, to support FM clerkships as the location within the undergraduate curriculum to house comprehensive transgender and GAH education. Current advocacy for inclusion of comprehensive transgender and GAH in FM clerkships not only continues to emphasize the broad nature of the specialty, but also stresses family medicine’s inherent prioritization of preventive and patient-centered care.18 These emphases create a starting place for teaching about the needs of transgender patients.

As with all survey research, this study has limitations. The cross-sectional nature of this survey limits the results to the views of FM clerkship directors at a single point in time. A risk exists that FM clerkship directors not responding to the survey have different beliefs than respondents or that FM clerkship director turnover limits applicability to current FM clerkship directors. However, given the representation of AAMC schools in both Canada and the United States, and the high response rate, it is likely this sample is representative. The possibility responses reflect perceived expected answers exists, but the anonymous construct of the CERA surveys and the regularity of use should mitigate this effect. An additional limitation is the academic affiliation of FM clerkship directors completing this survey, which may alter the makeup of their clinical practice as well as the beliefs of the people with whom they work from that of family physician practices as a whole. This may limit applicability of these results to FM clerkships utilizing large numbers of community practices as training sites.

Arguably, FM clerkships are primed for inclusion of comprehensive transgender and GAH education. Continued institutional advocacy for inclusion of comprehensive transgender and GAH in the medical school curriculum as well as more specific advocacy for inclusion in the clinical years will accelerate medical student exposure. The development of curricular materials easily integrated into already busy FM Clerkships may expedite this transition. Further research into facilitators and barriers of comprehensive transgender and GAH education inclusion in FM clerkships, especially mechanisms for improving comfort teaching this topic, is warranted.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: This study was presented as a poster titled “Transgender education in family medicine clerkships: A CERA Study,” at the 2019 North American Primary Care Research Group Annual Meeting, November, 2019, Toronto, Ontario, Canada.

References

- Gardner IH, Safer JD. Progress on the road to better medical care for transgender patients. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2013;20(6):553-558. doi:10.1097/01.med.0000436188.95351.4d

- Buchholz L. Transgender care moves into the mainstream. JAMA. 2015;314(17):1785-1787. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.11043

- Stroumsa D. The state of transgender health care: policy, law, and medical frameworks. Am J Public Health. 2014;104(3):e31-e38. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2013.301789

- Khalili J, Leung LB, Diamant AL. Finding the perfect doctor: identifying lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender-competent physicians. Am J Public Health. 2015;105(6):1114-1119. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2014.302448

- Roberts TK, Fantz CR. Barriers to quality health care for the transgender population. Clin Biochem. 2014;47(10-11):983-987. doi:10.1016/j.clinbiochem.2014.02.009

- McPhail D, Rountree-James M, Whetter I. Addressing gaps in physician knowledge regarding transgender health and healthcare through medical education. Can Med Educ J. 2016;7(2):e70-e78. doi:10.36834/cmej.36785

- Bonvicini KA. K.A. B. LGBT healthcare disparities: what progress have we made? Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(12):2357-2361. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2017.06.003

- Marr A, Tang K, Feder SH, Khatchadourian K, Lawson ML, Robinson A. Gender diversity training in Canadian paediatric postgraduate medical education: A needs assessment survey. Paediatr Child Health. 2019;26(2):e89-e95. doi:10.1093/pch/pxz144

- Morris M, Cooper RL, Ramesh A, et al. Training to reduce LGBTQ-related bias among medical, nursing, and dental students and providers: a systematic review. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):325. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1727-3

- Safer JD, Pearce EN; J. S. A simple curriculum content change increased medical student comfort with transgender medicine. Endocr Pract. 2013;19(4):633-637. doi:10.4158/EP13014.OR

- Cherabie J, Nilsen K, Houssayni S. Transgender Health Medical Education Intervention and its Effects on Beliefs, Attitudes, Comfort, and Knowledge. Kans J Med. 2018;11(4):106-109. doi:10.17161/kjm.v11i4.8707

- Bonvicini KA. LGBT healthcare disparities: what progress have we made? Patient Educ Couns. 2017;100(12):2357-2361. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2017.06.003

- Gardner IH, Safer JD; I.H. G. Progress on the road to better medical care for transgender patients. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2013;20(6):553-558. doi:10.1097/01.med.0000436188.95351.4d

- White Hughto JM, Reisner SL, Pachankis JE. Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc Sci Med. 2015;147:222-231. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2015.11.010

- Cruz TM. Assessing access to care for transgender and gender nonconforming people: a consideration of diversity in combating discrimination. Soc Sci Med. 2014;110:65-73. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.03.032

- Fallin-Bennett K. Implicit bias against sexual minorities in medicine: cycles of professional influence and the role of the hidden curriculum. Acad Med. 2015;90(5):549-552. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000662

- Grant JM. Mottet L a, Tanis J, Harrison J, Herman JL, Keisling M. Injustice at Every Turn: A Report of the National Transgender Discrimination Survey. Washingt Natl Cent Transgender Equal Natl Gay Lesbian Task Force. 2011;25:2011. doi:10.1016/S0016-7878(90)80026-2

- Radix AE. Addressing needs of transgender patients: the role of family physicians. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020;33(2):314-321. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2020.02.180228

There are no comments for this article.