Background and Objectives: Community engagement (CE), including community-engaged research, is a critical tool for improving the health of patients and communities, but is not taught in most medical curricula, and is even rarer in leadership training for practicing clinicians. With the growth of value-based care and increasing concern for health equity, we need to turn our attention to the benefits of working with communities to improve health and health care. The objective of this brief report is to increase understanding of the perceived benefits of CE training for primary care clinicians, specifically those already working.

Methods: We assessed perceived benefits of CE training for primary care clinicians participating in health care transformation leadership training through analysis of learner reflection papers.

Results: Clinicians (n=12) reported transformational learning and critical shifts of perspective. Not only did they come to value and understand CE, but the training changed their perception of their roles as clinicians and leaders.

Conclusions: Educating primary care clinicians in CE as a foundational principle can orient them to the criticality of stakeholder engagement for daily practice, practice transformation, and population health improvement, and provides them with a new understanding of their roles as clinicians and leaders.

The United States spends more per capita on health care than other developed nations, yet has worse health outcomes.1 As we work to improve the nation’s health, we need to train primary care clinicians to engage with communities to transform health care delivery and address social drivers of health (SDOH).2

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, community engagement (CE) is

the process of working collaboratively with and through groups of people affiliated by geographic proximity, special interest, or similar situations to address issues affecting the well-being of those people.3

CE can improve the health of disadvantaged populations and enhance program feasibility, quality, and sustainability,2 and primary care clinicians are well positioned to partner with communities to transform clinical care and SDOH.4 Since the creation of Clinical and Translational Science Awards in 2006, there has been a growth in CE training for researchers and communities, but we found little evidence that these lessons have been adopted broadly in medical education curricula.10 Despite growing attention to related concepts of SDOH and service learning, only a small number of schools train learners to collaborate with communities to design and implement research or population health improvement initiatives. A small amount of literature describes CE training in undergraduate medical training.5-9 A systematic review of leadership development programs for practicing physicians revealed no evidence of CE in the curricula, despite the need to make it more central in academic medical centers.3,11,12

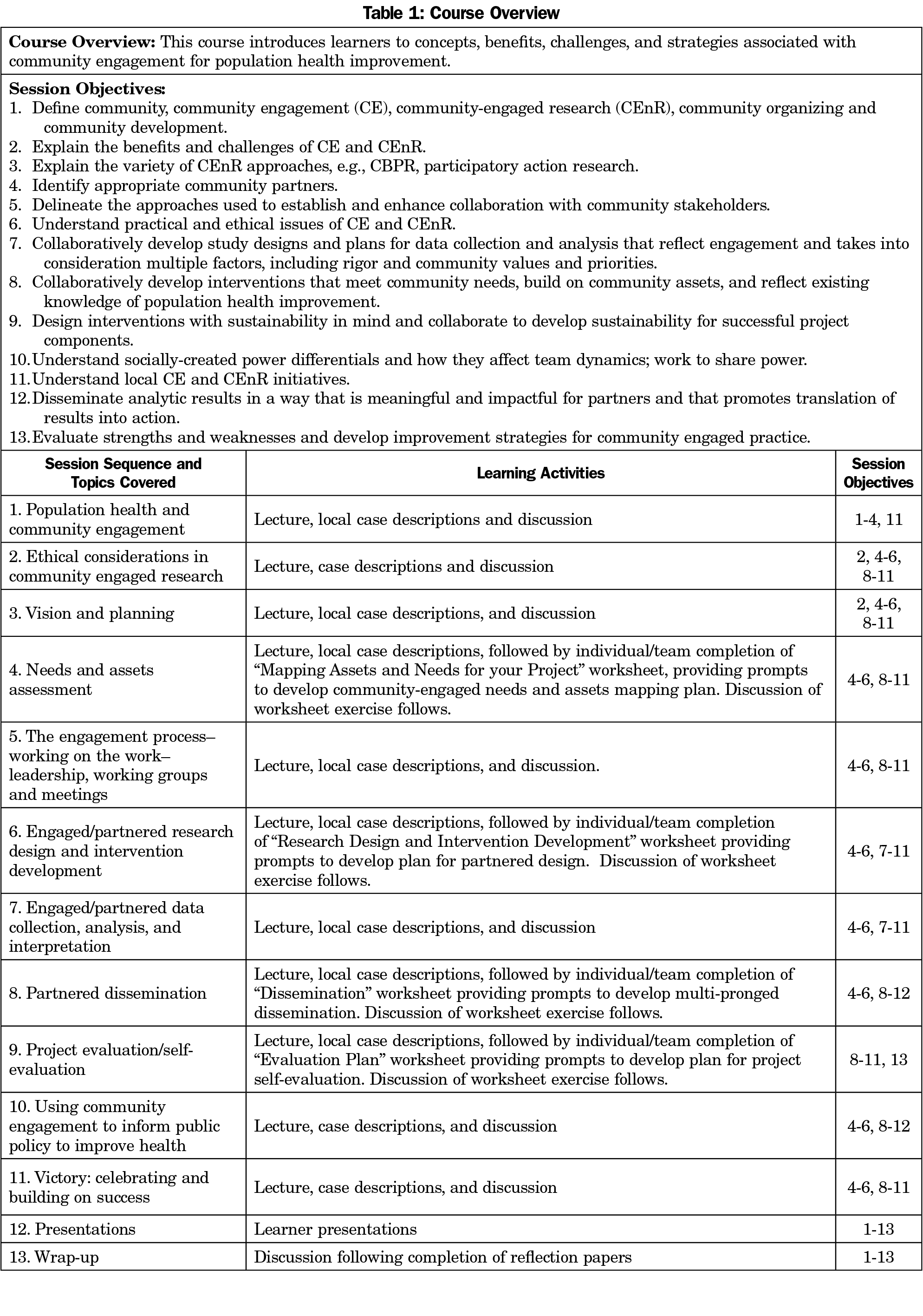

The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) is sponsoring primary care transformation fellowships to train physicians and physician assistants to lead health care transformation and improve health in their communities. Duke Department of Family Medicine and Community Health’s 2-year Primary Care Transformation Fellowship (PCTF) curriculum begins with a course on CE strategies and practices titled “Community Engaged Approaches to Health Improvement.” The course introduces CE, including community-engaged research (CEnR), and explores CE programs and initiatives as tools for population health improvement. The course aims to provide learners with an appreciation for the value of CE and its challenges, develop their basic skills in CE, and let them practice those skills through a hands-on project. Finally, they are introduced to resources to assess and develop their engagement practice. Table 1 provides greater detail on the course. This paper describes what the fellows have gained from this training in CE.

Cohort 1 (2019) consisted of three MD’s and four physician assistants, and Cohort 2 (2020) consisted of two MD’s and three physician assistants. Each fellow was required to write a reflection paper (approximately 10 pages in length) on the ways in which learning about CE has impacted their work, career, and their understanding of health improvement. At end of the course, students presented their project work to date and turned in the reflection paper. We used a general inductive approach for analysis.13 The codebook was developed by two reviewers and modified by consensus; one reviewer did primary coding and analysis with verification by the second. We are attentive in analysis to being clear as to when we could and could not attribute fellow knowledge and attitudes to the course. The Duke University institutional review board exempted this research from formal review.

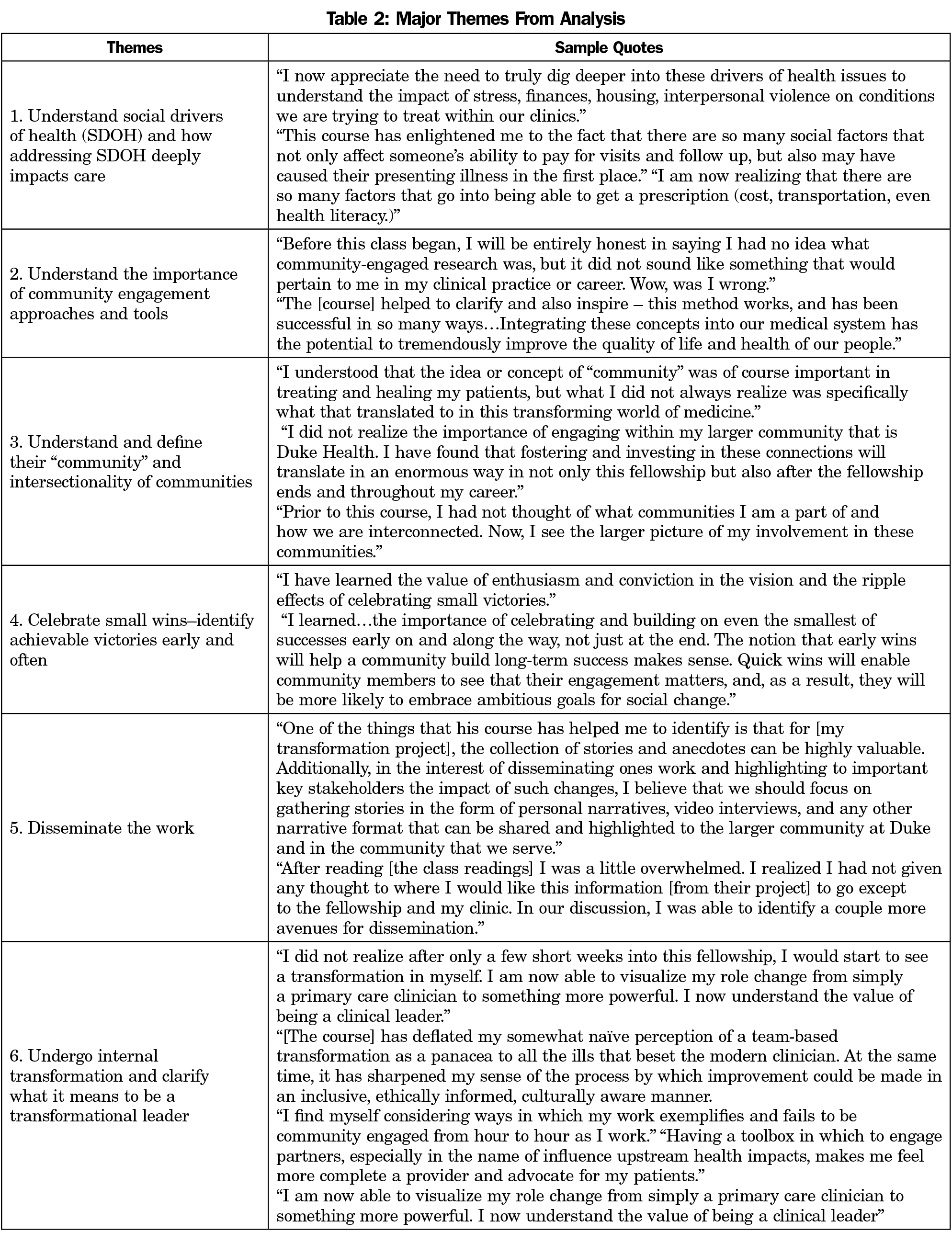

Six major themes were identified from the papers (Table 2). Each appeared in at least four papers, with some occurring in as many as nine. We observed no pattern of difference for physician assistants and MDs.

Theme 1: Understand SDOH and How Addressing SDOH Deeply Impacts Care

More than half of fellows had some prior understanding of SDOH, but gained greater depth in their understanding of SDOH from the course. The concept of SDOH was new to others. One mentioned having a “light bulb” moment, realizing the significance of how SDOH affect a person’s health and ability to stay healthy.

Theme 2: Understand the Importance of CE Approaches and Tools

Fellows were struck by the pertinence of CE to their work and noted the importance of valuing and prioritizing what the community needs and wants. Three fellows referenced that successfully navigating partnership requires a great deal of work, dedication, and attention to detail.

Theme 3: Understand and Define Their Community and Intersectionality of Communities

Fellows realized that engaging a community requires first defining it. They developed a new appreciation for the different communities they are part of, the value of one’s communities, and how communities are interrelated.

Theme 4: Celebrate Small Wins—Identify Achievable Victories Early and Often

For many fellows, the course brought to light the importance of identifying and celebrating small wins early and often to help create and maintain momentum.

Theme 5: Disseminate the Work

Fellows realized the importance of thinking early about strategies for dissemination of their work, including defining and understanding target audiences.

Theme 6: Undergo Internal Transformation and Clarify What It Means To Be a Transformational Leader

Fellows noted internal growth/transformation while taking the course. Strikingly, this went beyond understanding CE. For example, one fellow cited increased confidence and a new appreciation for the value of being a clinical leader; another said that they were redefining the clinical role. Another mentioned the importance of listening, maintaining humility, and communicating vision.

Our analysis revealed multiple benefits from CE training. Fellows reported that the course helped them understand how CE can shape strategies for daily practice, practice transformation, and broader civic engagement to promote health. More surprisingly, the benefits went beyond just learning about CE. Fellows conveyed that they grew as leaders, gained confidence, and redefined their role as clinicians. However, our analysis was limited due to the small sample size of only two classes of fellows, 12 in total.

As these fellows implement transformational fellowship projects, they now have tools for CE and can teach colleagues to authentically partner with communities to address their needs. Educating primary care clinicians in CE has the potential to improve the health of communities, make clinicians more effective leaders, and provide them with a broader understanding of their societal role. Additional research on the impact of CE training would shed further light on the value of integrating this topic into more curricula.

Acknowledgments

Financial Support: Financial support for this project was provided by the Duke Primary Care Transformation Fellowship Grant, and by HRSA-18-103 Primary Care Training and Enhancement: Training Primary Care Champions.

References

- Tikkanen R, Abrams MK. U.S. health care from a global perspective, 2019: higher spending, worse outcomes? Commonwealth Fund Issue Briefs. Janary 30, 2020. Accessed September 12, 2021. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/jan/us-health-care-global-perspective-2019

- Cyril S, Smith BJ, Possamai-Inesedy A, Renzaho AMN. Exploring the role of community engagement in improving the health of disadvantaged populations: a systematic review. Glob Health Action. 2015;8(1):29842. doi:10.3402/gha.v8.29842

- Clinical and Translational Science Awards Consortium Community Engagement Key Function Committee Task Force on the Principles of Community Engagement. Principles of community engagement: Second Edition. June 2011. Accessed September 12, 2021. https://www.atsdr.cdc.gov/communityengagement/pdf/PCE_Report_508_FINAL.pdf

- Prasad S, Westby A, Crichlow R. Family medicine, community, and race: a Minneapolis practice reflects. Ann Fam Med. 2021;19(1):69-71. doi:10.1370/afm.2628

- Girotti JA, Loy GL, Michel JL, Henderson VA. The urban medicine program: developing physician-leaders to serve underserved urban communities. Acad Med. 2015;90(12):1658-1666. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000970

- Haq C, Stearns M, Brill J, et al. Training in urban medicine and public health: TRIUMPH. Acad Med. 2013;88(3):352-363. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182811a75

- Meurer LN, Young SA, Meurer JR, Johnson SL, Gilbert IA, Diehr S; Urban and Community Health Pathway Planning Council. The urban and community health pathway: preparing socially responsive physicians through community-engaged learning. Am J Prev Med. 2011;41(4)(suppl 3):S228-S236. doi:10.1016/j.amepre.2011.06.005

- Powell T, Garcia KA, Lopez A, Bailey J, Willies-Jacobo L. University of California San Diego’s Program in Medical Education-Health Equity (PRIME-HEq): training future physicians to care for underserved communities. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(3):937-946. doi:10.1353/hpu.2016.0109

- Bullock K, Jackson BR, Lee J. Engaging communities to enhance and strengthen medical education: rationale and summary of experience. World Med Health Policy. 2014;6(2):133-141. doi:10.1002/wmh3.94

- Piasecki RJ, Quarles ED, Bahouth MN, et al. Aligning community-engaged research competencies with online training resources across the Clinical and Translational Science Award Consortium. J Clin Transl Sci. 2020;5(1):e45. doi:10.1017/cts.2020.538

- Chung B, Brown A, Moreno G, et al. Implementing community engagement as a mission at the David Geffen School of Medicine at the University of California, Los Angeles. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2016;27(1):8-21. doi:10.1353/hpu.2016.0009

- Wilkins CH, Alberti PM. Shifting academic health centers from a culture of community service to community engagement and integration. Acad Med. 2019;94(6):763-767. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002711

- Thomas DR. A general inductive approach for analyzing qualitative evaluation data. Am J Eval. 2006;27(2):237-246. doi:10.1177/1098214005283748

There are no comments for this article.