Background and Objectives: Health policy is more impactful for public health than many other strategies as it can improve health outcomes for an entire population. Yet in the “see one, do one, teach one” environment of medical school, most students never get past the “see one” stage in learning about the powerful tools of health policy and advocacy. The University of New Mexico School of Medicine mandates health policy and advocacy education for all medical students during their family medicine clerkship rotation. The aim of this project is to describe a unique health policy and advocacy course within a family medicine clerkship.

Methods: We analyzed policy briefs from 265 third-year medical students from April 2016 through April 2019. Each brief is categorized by the level of change targeted for policy reform: national, state, city, or university/school. Implemented policies are described.

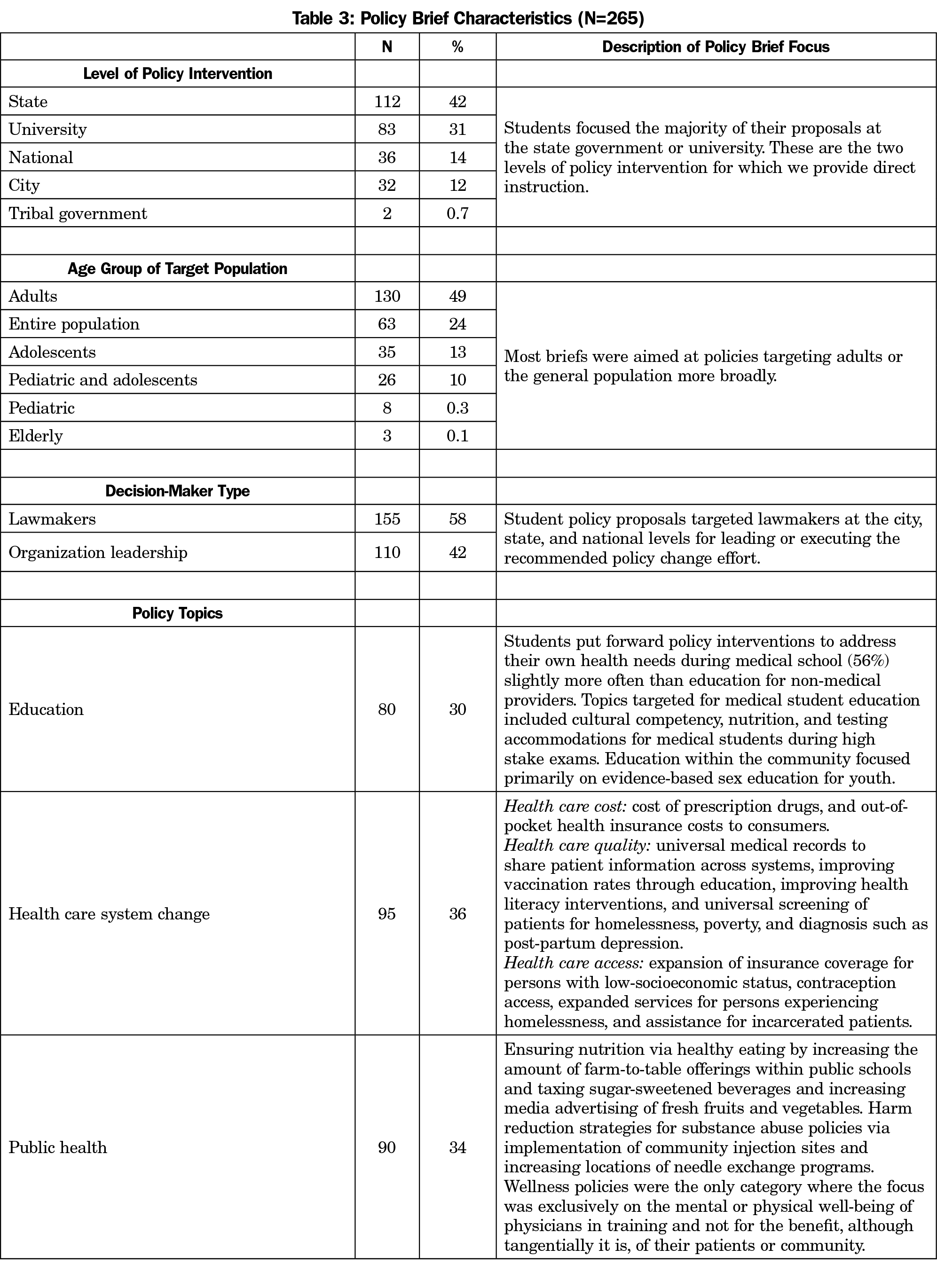

Results: Slightly less than one-third of the policies (30%) relate to education, 36% advocate for health system change by addressing cost, access, or quality issues, and 34% focus on public health issues. Fourteen policies have been initiated or successfully enacted.

Conclusions: This curriculum gives each medical student a health policy tool kit with immediate opportunities to test their skills, learn from health policy and advocacy experts, and in some cases, implement health policies while still in medical school. A 1-week family medicine policy course can have impact beyond the classroom even during medical school, and other schools should consider this as a tool to increase the impact of their graduates.

Physicians are trained to educate and counsel individual patients to make good choices for wellness, but a potentially more significant impact can be made by physicians who advocate and intervene at the policy level. As clinical experts and advocates on the local, state, and national levels, providers can multiply their power to address health inequities substantially. Empowering medical students to serve as advocates can prepare them for key roles in shaping our health care system and opportunities that impact populations. Furthermore, medical students desire training in health policy and advocacy.1-4

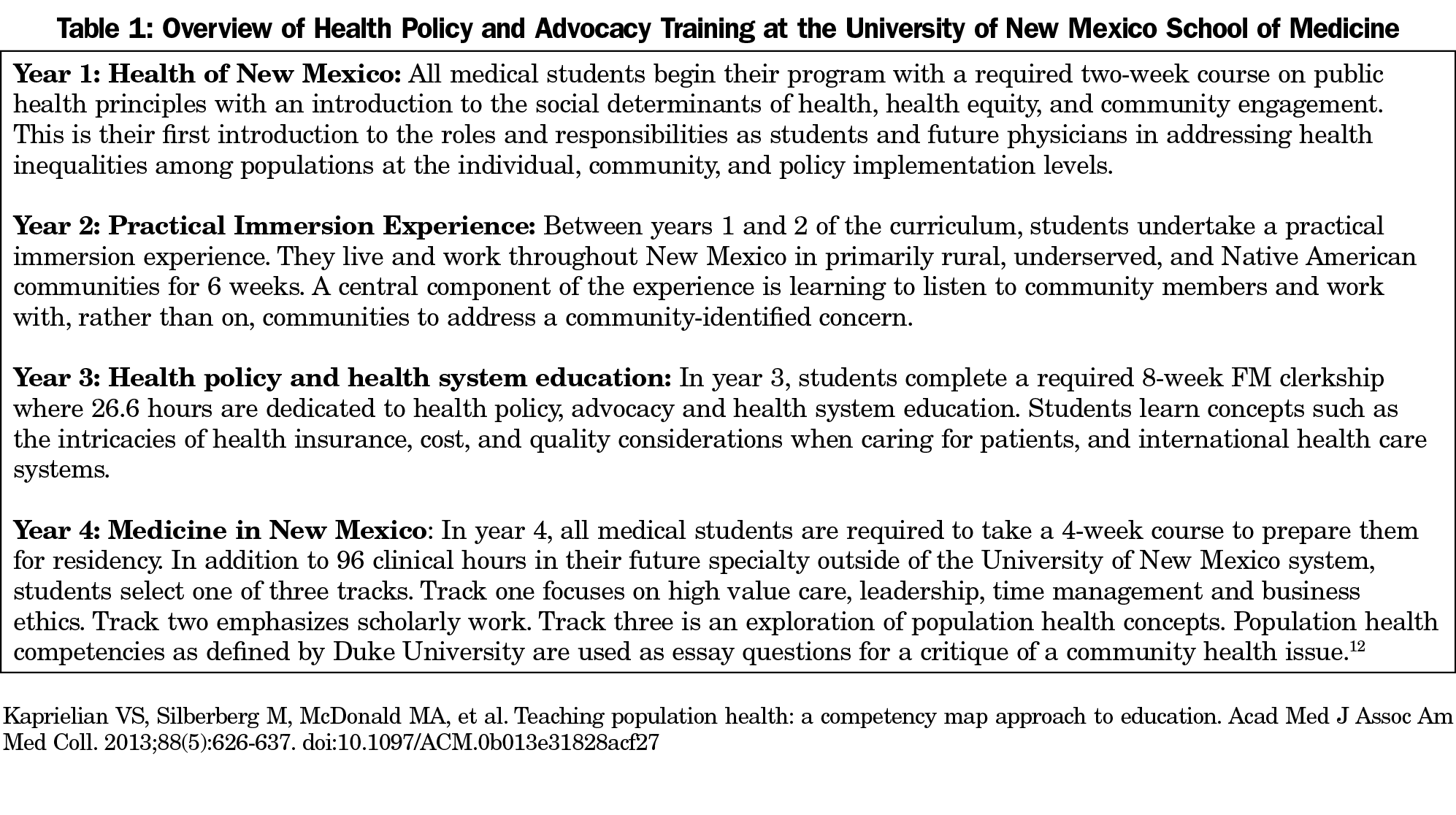

Community immersion and advocacy is an integral part of the University of New Mexico School of Medicine curriculum. Aspects are taught longitudinally in all 4 years (Table 1). During year 3, an approach to advocacy by using a health policy approach is taught within the family medicine (FM) clerkship because, as the American Academy of Family Physicians notes,

These specialists, because of their background and interactions with the family, are best qualified to serve as each patient’s advocate in all health-related matters…5

The clerkship clinical time was condensed into 7 weeks to allow for an eighth week consisting of 40 hours of didactics and skills training with 26.6 of these hours dedicated to health policy and advocacy education.6 Students learn how to advocate using a written policy brief and then simulating real-world advocacy by presenting their ideas to FM instructors and clerkship cohort peers. We encourage students to actively pursue implementation of their ideas, but due to curriculum time constraints, it is not mandatory.

This paper describes the outcomes of the FM health policy and advocacy clerkship course. We conducted a qualitative review of medical student policy briefs submitted as part of the FM clerkship requirements to categorize what type of policies students identify for change, at what level change needs to occur, and the extent to which students framed policy interventions to address population health outcomes.

Table 2 details the Health Policy and Advocacy Course design. We coded 293 deidentified student policy briefs submitted between April 2016 and April 2019. Authors N.A. and C.B. inductively coded themes from the topic and subtopic of each policy brief. Authors A.C.E. and D.A. categorized and condensed themes into categories. Where discrepancies occurred, A.C.E. reviewed the full briefs to verify codes. A.C.E. and D.A. then used a consensus process to determine where the brief belonged. Frequencies are reported to give context to the findings. We used an Excel spreadsheet to manage data. Variables of interest are defined below.

Level of Policy Intervention

We categorized responses by the level of policy intervention. Levels were state, university, national, city, or tribal government.

Decision Makers

We identified decision-makers as formal law-making bodies or organizations. A comparison between the level of intervention and type of decision-maker was made to verify appropriateness for policy intervention’s corresponding level.

Age of Target Population

We categorized each brief into age groups for the target population of the policy intervention: pediatric (ages 9 years and under), adolescent (ages 10-17), pediatric and adolescent (target policy proposal that included both age groups), adults (ages 18-64), elderly (ages 65+), or total population.

Topics

We first categorized topics using the National Academy of Medicine triple aim of cost, access, and quality, and inductively identified topics for the health or system problem(s) and proposed solutions(s).7 Student topics were then organized into eight categories (in order of frequency from highest to lowest): education, access, injury prevention, quality, nutrition, health care cost, and substance abuse. Finally, we condensed these into three groups for results reporting:

- Education proposals related to medical education specifically and public education more broadly;

- Topics from briefs proposing changes for the health care system: health care cost, quality, and access; and

- Public health intervention-focused and includes injury prevention, substance use, and wellness.

Outcomes

We describe results on two outcome measures: attempted and successful implementation of student policy briefs and FM clerkship student evaluation results.

The University of New Mexico Human Research and Review Committee exempted this study (HRRC 19-229).

Of the 293 briefs, 28 were duplicate entries or missing a significant amount of information. We report results based on the 265 briefs.

Policy Characteristics

Table 3 summarizes the level of policy intervention, age group affected by the policy intervention, the type of decision-maker, and student topics.

Outcomes

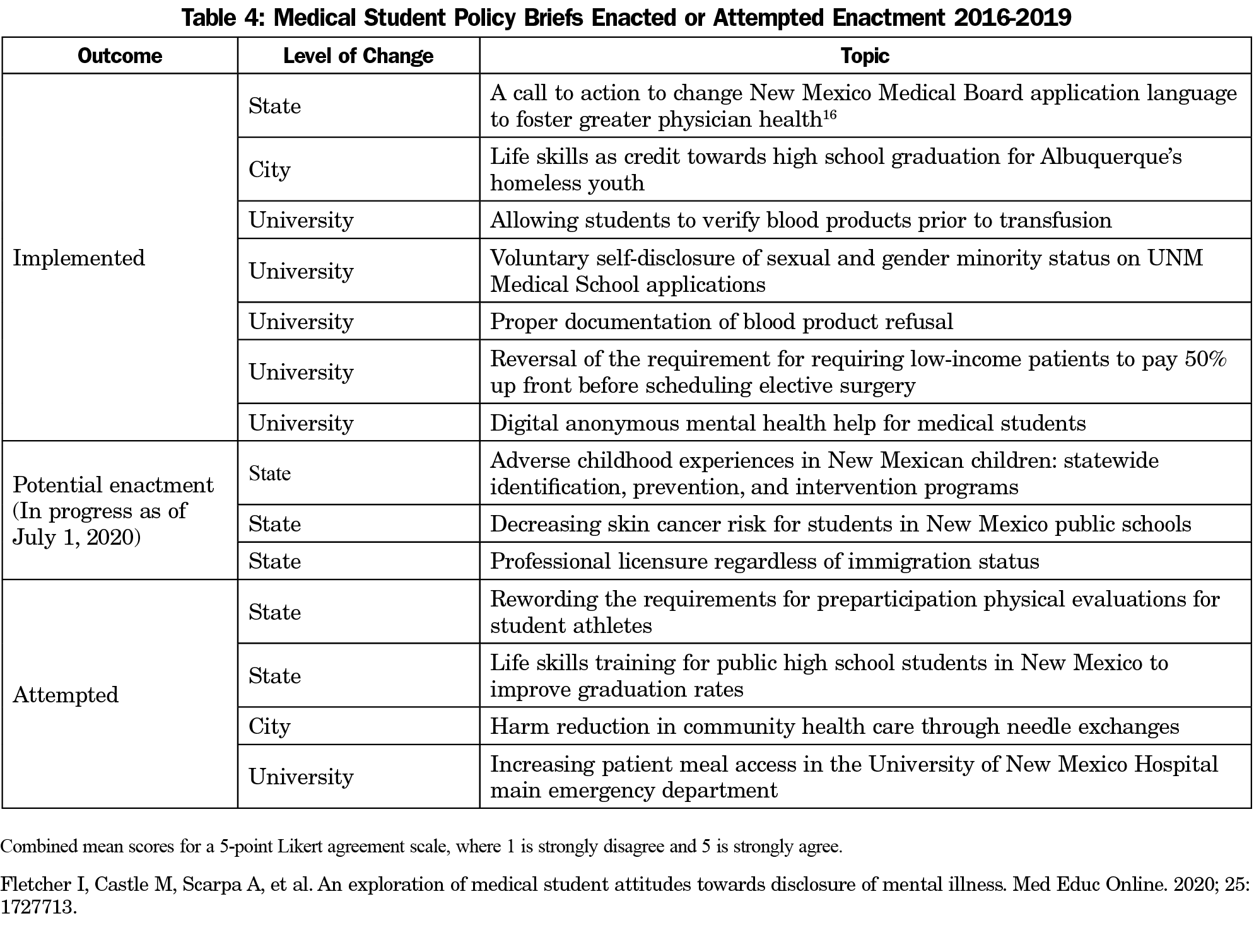

Although not required, 14 students attempted to implement their policy proposals. Six proposals were implemented.

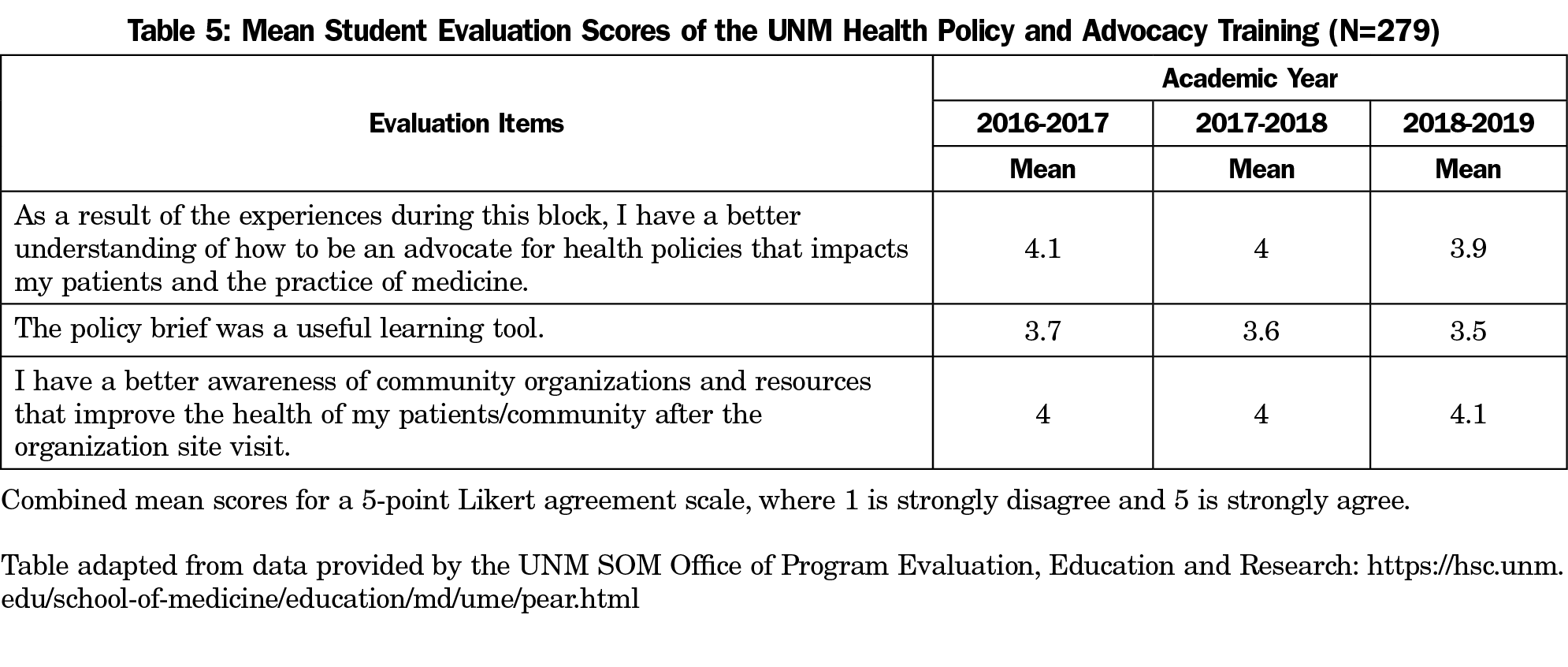

Overall, students report positive learning experiences from the policy education in their evaluations, but average a neutral score on the policy brief assignment (Tables 4 and 5).

Final course evaluations suggest not all students fully embrace the policy brief assignment, but they report the experience positively influences their overall understanding and appreciation for the impact of health policy and advocacy. The neutral findings were reflective of some not caring about the assignment and some embracing it as another tool for advocacy. A few students attempted to implement their ideas, with some notable successes. This finding from our student evaluation confirms studies that found that physicians deemed community participation and advocacy important within their careers.11,12

Health policy training has a positive impact on medical students because it helps shape professional roles by assisting students in identifying their role as an advocate.8-10 Interactions outside the classroom with community advocacy groups permitted our students to learn how to engage in advocacy for real-world issues that affect their patients and community.

This study was a retrospective collection of policy briefs, which limited the data to the completed assignment and does not allow for direct analysis of the student’s choices. Further, we are unable to address the outcomes of proposals that were implemented, nor can we explain why others were not implemented.

The American Medical Association holds that physicians must:

advocate for social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human well-being.13

There is a role for health policy training for medical students.14,15 This curriculum gives each student a health policy toolkit with immediate opportunities to test their skills, learn from health policy and advocacy experts, and implement health policies while still in medical school. Research is needed on whether these experiences increase actual participation in health policy and advocacy in future clinical practice. Nonetheless, it is essential that medical students are trained in health policy as a form of advocacy as future stewards of individual and community health.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the UNM DFCM Writing Accountability Group for their assistance with this project.

References

- Mou D, Sarma A, Sethi R, Merryman R. The state of health policy education in U.S. medical schools. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(10):e19. doi:10.1056/NEJMp1101603

- Agrawal JR, Huebner J, Hedgecock J, Sehgal AR, Jung P, Simon SR. Medical students’ knowledge of the U.S. health care system and their preferences for curricular change: a national survey. Acad Med. 2005;80(5):484-488. doi:10.1097/00001888-200505000-00017

- Croft D, Jay SJ, Meslin EM, Gaffney MM, Odell JD. Perspective: is it time for advocacy training in medical education? Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1165-1170. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31826232bc

- Dharamsi S, Ho A, Spadafora SM, Woollard R. The physician as health advocate: translating the quest for social responsibility into medical education and practice. Acad Med. 2011;86(9):1108-1113. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318226b43b

- Family Physician, Definition. AAFP Policies. Accessed May 10, 2016. http://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/fp-definition.html

- Cole McGrew M, Wayne S, Solan B, Snyder T, Ferguson C, Kalishman S. Health policy and advocacy for New Mexico medical students in the family medicine clerkship. Fam Med. 2015 Nov-Dec;47(10):799-802.

- Institute of Medicine. Core Measurement Needs for Better Care, Better Health, and Lower Costs: Counting What Counts: Workshop Summary. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press; 2013. doi:10.17226/18333

- Quraishi SA, Orkin FK, Weitekamp MR, Khalid AN, Sassani JW. The Health Policy and Legislative Awareness Initiative at the Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine: theory meets practice. Acad Med. 2005;80(5):443-447. doi:10.1097/00001888-200505000-00006

- Press VG, Fritz CDL, Vela MB. First year medical student attitudes about advocacy in medicine across multiple fields of discipline: analysis of reflective essays. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2015;2(4):556-564. doi:10.1007/s40615-015-0105-z

- Belkowitz J, Sanders LM, Zhang C, et al. Teaching health advocacy to medical students: a comparison study. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2014;20(6):E10-E19. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000000031

- Dobson S, Voyer S, Regehr G. Perspective: agency and activism: rethinking health advocacy in the medical profession. Acad Med. 2012;87(9):1161-1164. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182621c25

- Gruen RL, Campbell EG, Blumenthal D. Public roles of US physicians: community participation, political involvement, and collective advocacy. JAMA. 2006;296(20):2467-2475. doi:10.1001/jama.296.20.2467

- AMA Declaration of Professional Responsibility. American Medical Association. Accessed January 4, 2021. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/ama-declaration-professional-responsibility

- Emil S, Nagurney JM, Mok E, Prislin MD. Attitudes and knowledge regarding health care policy and systems: a survey of medical students in Ontario and California. CMAJ Open. 2014;2(4):E288-E294. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20130094

- Patel MS, Lypson ML, Miller DD, Davis MM. A framework for evaluating student perceptions of health policy training in medical school. Acad Med. 2014;89(10):1375-1379. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000000408

There are no comments for this article.