Background and Objectives: The College of Family of Physicians of Canada’s Certificates of Added Competence (CACs) denote enhanced-skill family physicians who function beyond the scope of family practice or in specialized areas fundamental to family medicine practice. The credential provides recognition for skill development in areas of need and is intended to augment comprehensive care; however, there are concerns that it increases focused practice and decreases commitment to generalist care. To inform credentialing policies, we elucidated physician and trainee motivations for pursuing the CAC credential.

Methods: We conducted secondary analyses of interview data collected during a multiple case study of the impacts of the CACs in Canada. We collected data from six cases, sampled to reflect variability in geography, patient population, and practice arrangement. The 48 participants included CAC holders, enhanced-skill family physicians, generalist family physicians, residents, specialists, and administrative staff. We subjected data to qualitative descriptive analysis, beginning with inductive code generation, and concluding in unconstrained deduction.

Results: Family physicians and trainees pursue the credential to meet community health care needs, limit or promote diversity in practice, secure perceived professional benefits, and/or validate their sense of expertise. Notably, family physicians face barriers to engaging in enhanced skill training once their practice is established.

Conclusions: While the CACs can enhance community-adaptive comprehensive care, they can also incentivize migration away from generalist practice. Credentialing policies should support enhanced skill designations that respond directly to pervasive community needs.

The College of Family Physicians of Canada (CFPC; “The College”) credentials family physicians with enhanced skills via a suite of Certificates of Added Competence (CACs).1 Through defined eligibility criteria, a structured review process, and CFPC Board of Examiners-approved standards of assessment, the CAC recognizes the achievement of additional competence in a set of health care domains: emergency medicine (EM), palliative care (PC), care of the elderly (COE), family practice anesthesia (FPA), sports and exercise medicine (SEM), addictions medicine (AM), enhanced surgical skills (ESS), and obstetrical surgical skills (OSS). As of August 2021, the College has awarded 6,045 CACs (EM=3,842; PC=617; COE=425; FPA=430; SEM=360; AM=292; ESS=26; OSS=53). The CACs are roughly equivalent to the Certificates of Added Qualification (CAQs) offered by the American Board of Family Medicine, which designate enhanced skills for family physicians in 10 domains of specialized or subspecialized medicine.2 Designations such as these are one way of denoting family physicians who provide services that fall outside the traditional scope of family physician skills (eg, family practice anesthesia, enhanced surgical skills) or that are associated with specialized advances in aspects of care that are considered fundamental components of family medicine practice (eg, palliative care, care of the elderly).

In establishing training and certification standards in the CAC domains, the CFPC aims to incentivize skill development and practice in areas of particular need in Canada. Furthermore, the College has an explicit expectation that those who hold the certificates will apply this added competence to support comprehensive community-adaptive care that avows the principles of family medicine3 and that relies upon a collaborative interdependence between health care professionals.4,5 That is, the College hopes that CAC holders will align themselves with local generalist practices to expand the comprehensiveness of care within communities. However, this credentialling policy, like all policies, is potentially challenged by unintended consequences.6 Indeed, there is consternation that the certificates are having a confounding effect: stimulating an increase in focused practice and promoting a decreased commitment to generalist care.7-11 In this regard, our research team recently completed a large, pan-Canadian, multiple case study of the impacts of the CACs on comprehensive, community-adaptive care in Canada. This work affirmed the notion that some CAC holders focus their practices in a way that is not aligned with the needs of the community and its local generalist family physicians.12 Notably, this tendency is seemingly influenced by the practitioners’ personal and professional interests, a perspective that resonates with other research highlighting that work-life balance and remuneration are tremendously influential on the choices that physicians make about family medicine practice,7, 13-18 most typically discouraging comprehensive, generalist practices.

To determine how the College might better align the CACs and related policy to support their vision for family medicine practice in Canada, there is a clear need to better understand what motivates family physicians and resident trainees to pursue a Certificate of Added Competence. Accordingly, we present here a secondary analysis of data collected through our pan-Canadian study that offers a detailed qualitative description of the personal perspectives and experiences that influence decisions about undertaking a CAC. In doing so, we elucidate the reasons practitioners and trainees wish to attain the certificate, their perceptions of its professional relevance, and the barriers that they may experience in their pursuit. On this foundation, we make normative recommendations that may enhance the degree to which the certificates support the delivery of comprehensive, community-based care in Canada.

Study Design

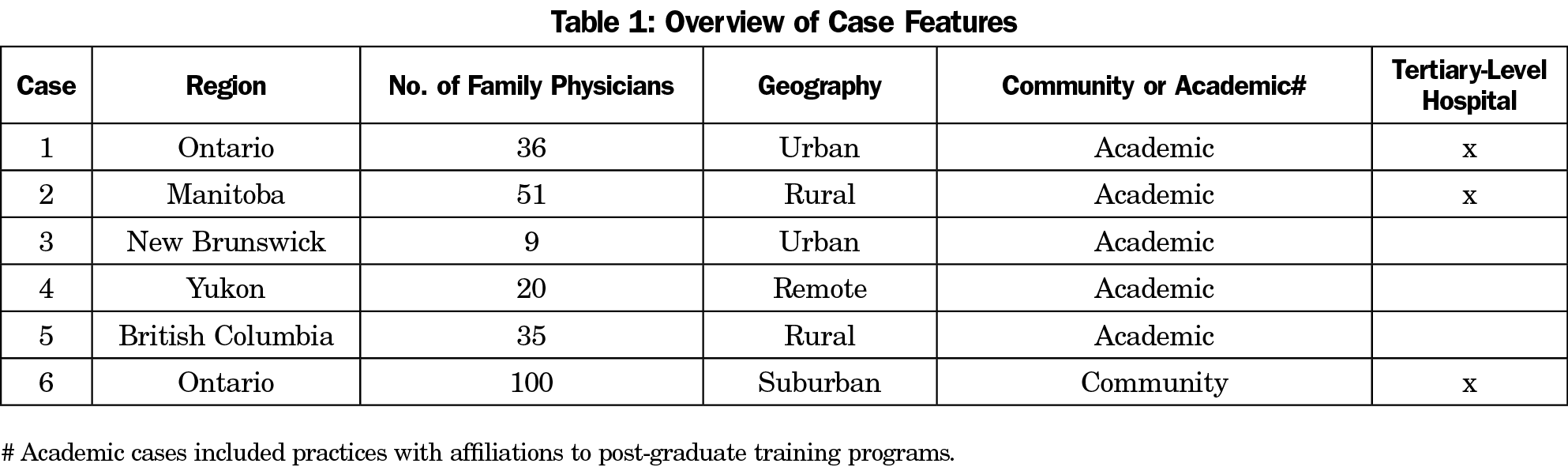

This is a secondary analysis of data generated through a multiple case study of how the CACs impact primary care in Canada. This secondary analysis adheres to the methodological details published in the original study.12 In summary, the study began with four exploratory case studies and progressed through two additional exploratory-explanatory case studies.19 We defined a case as a collective of family physicians working in an interconnected community, having contact with the same group of patients. We determined exploratory cases in consultation with representatives from regions with a high concentration of CAC holders; selected on the basis of maximum variation in geography, population density, language, patient population, and practice models. Invitations to participate were issued by the CFPC on behalf of the research team. We similarly selected exploratory-explanatory cases with consideration for maximal variation, but also for the way in which their particular characteristics afforded the opportunity to test the analytic generalizability of the propositions developed in the exploratory case studies. Table 1 details case characteristics.

Data Collection

In all cases, the selected practice groups were invited to participate in semistructured interviews. Eligible participants were professionals whose work was related to the identified case, including CAC holders, other enhanced skill family physicians (ES), generalist family physicians (GEN), resident trainees, specialist physicians, nonphysician clinicians, and administrative staff. Our approach to recruitment combined purposeful, criterion, and snowball sampling techniques that ensured that selected participants were appropriately situated to offer insight into specific features of our emerging understanding of the impact of CACs in Canada. We ceased recruitment when data sufficiency was determined, related to data completeness within each case.19 Our first interviews were guided by a set of initial theoretical propositions12 that were based on a review of relevant literature,7-11,20-22 the 4 Principles of Family Medicine,3 and the goals for family medicine practice articulated in the CFPC’s Patient’s Medical Home vision statement4 and Family Medicine Professional Profile.5

Data Analysis

All interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. Once in textual form, we first analyzed data within case, and then across cases. We used a descriptive approach to qualitative analysis, engaging in a staged process of coding. For the exploratory cases, this involved inductive code generation that was simultaneously mindful of our initial theoretical propositions as well as any codes generated through earlier cases. Initial coding summarized the content and condensed it into categories concerning individual motivations. Subsequent iterations of analysis refined the coding. We used an unconstrained deductive approach to analyze the two exploratory-explanatory cases based on the coding framework developed from the first four exploratory cases.23 Author L.G. led the analysis with assistance from authors I.A. and M.V. The full research team met regularly to acknowledge, discuss, and reconcile the impacts our positions, perspectives, and preconceived biases may have had on the analysis. Furthermore, we engaged regularly with CFPC stakeholders to incorporate perspectives from the College’s academic, research, education, and CAC committees as we progressed (see Grierson et al12 for details about our engagement with the College). We managed data via N-Vivo12 software. Analysis concluded with the development of a cogent articulation of the motivations, perceptions, and barriers that family physicians and resident trainees in Canada have concerning CACs.

Ethics Approval

The Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board approved this study (HIREB #5151). All participants provided informed consent prior to joining the study.

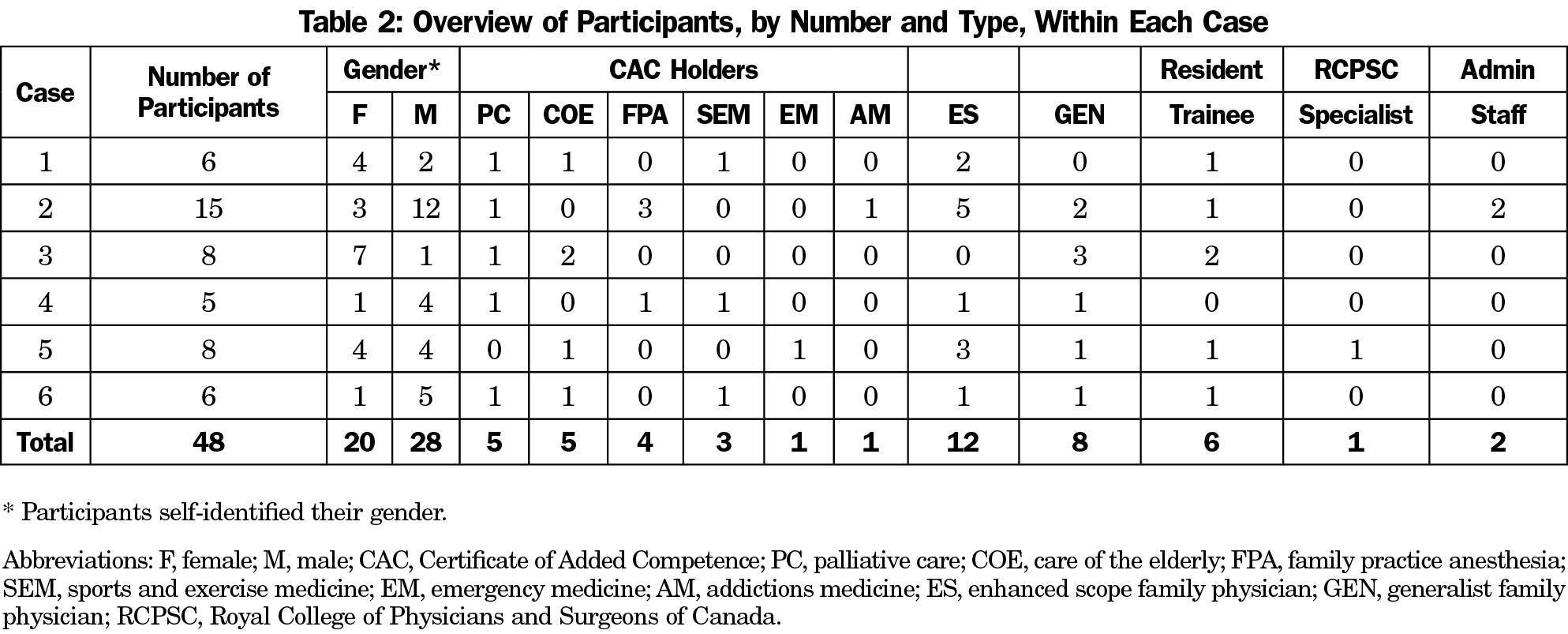

In total, data included contributions from 48 individuals, including six trainees and several early-career family physicians who described the factors that influenced their decisions during training. Table 2 provides an overview of participant characteristics associated with each case. We describe the variety of motivations articulated by family physicians and resident trainees as influential of their choice to pursue enhanced skill training.

To Meet the Health Care Needs of the Community

For many of the established family physicians that we interviewed, the motivation to pursue enhanced skill work was to be responsive to the health care needs of their community:

“I feel heavily committed to this one location so if I was going to pursue extra training, it would be in conversation with the other physicians who work here.” (Case 2 Participant 3, GEN)

This idea was mirrored by many trainees who indicated that they aspire to the certificate because they intend to work in regions where enhanced skill work is anticipated to be particularly useful. For instance, individuals who hoped to work in rural contexts perceived enhanced skill practice as important to address gaps in health care delivery in these communities:

“The whole reason I did anaesthesia in the first place was to be comfortable working in a rural emergency room.” (Case 2 Participant 2 CAC, FPA)

To Limit or Promote Diversity in the Scope of Clinical Practice

A strong motivation represented in the data was that enhanced skill work was desirable because it facilitated approaches to practice that avoided difficult and/or underresourced aspects of generalist family practice:

“I also think people just want to get away from family practice. That’s why I feel like we’re going to see more people wanting to get into these little niches.” (Case 5 Participant 8 ES, Oncology; application for CAC PC denied)

For resident trainees and recent graduates, this idea of managing practice scope through enhanced skill practice was also salient. Some felt a particular affinity for one part of family practice, while others articulated interest in bringing an enjoyable diversity to their generalist practice through the incorporation of enhanced skill work:

“I really enjoy it, I like the variety of the practice. I also, I love clinic, but I can’t do it that many days in a row.” (Case 2 Participant 1 CAC, FPA)

Other trainees and recent graduates were attracted to the idea of feeling confident within a well-defined scope of practice:

“I think that is a major draw in the way you’re trained in anaesthesia is to have a sense of all the possible ways things could go wrong or all the things that you have to do. And there’s a bit of a security in knowing, well, I know these are the things that I can do, and these are the things that I would do in these situations and it falls into this narrow spectrum. Whereas in family practice and clinic practice, it seems endless. The breadth is just daunting. So, there’s a draw to a more focused part of medicine where you can feel more comfortable, even if it is more acute and maybe more dangerous but you know where your limits are, and you know what you can do.” (Case 2 Participant 3 Trainee)

Numerous trainees and early-career physicians described a perception that enhanced skill practices would permit better remuneration and better work-life balance:

“I didn’t want to be office-based, I preferred to be hospital-based. I enjoyed being in the hospital and when I was in the hospital I was working and when I wasn’t working, I would go home. I didn’t have to go to the office and secretaries, I didn’t have to worry about expenses, so for my personality it was a good fit.” (Case 5 Participant 3 ES, FPA)

Others expressed a desire to become academic, community, and/or clinical leaders and felt strongly that the certificate would facilitate this goal:

“I think the CAC program provides us, as continuing trainees, a little bit of expertise in that specific field and taking on more leadership roles and academic roles, in terms of furthering the field that way.” (Case 6 Participant 4 Trainee)

To Secure the Perceived Professional Benefits Associated With the College’s Accreditation

Many held the idea that the College’s backing of the CAC was indicative that the certificate would bring a variety of advantages, including becoming an explicit standard for attaining focused-practice designations. Indeed, most trainees and recent graduates interviewed held the belief that those responsible for hiring and privileging would value the CAC credential preferentially:

“Some positions are quite competitive now in terms of job opportunities. So, in the region I live currently, its actually quite difficult to get a nursing home position, for example, so I thought having extra training and extra experience in this field would provide me with the skills needed to be more competitive in the job market.” (Case 1 Participant 3 CAC, COE)

Most participants—established physicians and trainees alike—indicated an expectation that the College will lobby provincial and territorial authorities and advocate for CAC holders in their pursuit of practice designation, access to billing codes, and the organization of more favorable remuneration structures. The potential for this advocacy is perceived as a key benefit of pursuing the CAC designation where it is available. Indeed, many participants perceived incentives to focused, enhanced skill practice including higher remuneration, salaried fee structures, and improved control over work hours. They described that generalist care is primarily encouraged through policy edicts and contract agreements, rather than incentives. These were clearly motivating factors for the pursuit of enhanced-skill work:

“These certificates have created this playing field where those of us with them are going to get potentially financial advantages and job security, contract advantages with government.” (Case 4 Participant 2 CAC, COE)

In light of this, our data also revealed that participants recognize numerous options for pursuing enhanced skills practice, and that they need to make decisions about the programs and designations that best facilitate their goals. In this regard, that the College established the CACs served as a major motivator toward this particular designation:

“In general, I like official stuff. When this was offered to me, I thought, well, why not? Because this is one more paper confirming that I’m trained to do what I do. But also, because it’s something pan-Canadian and that’s coming from my direct origin, you know, family physicians of Canada.” (Case 4 Participant 3 CAC, SEM)

To Feel That Their Expertise is Valued

Across all cases, we heard that established family physicians were motivated to pursue the certificate because of the way it seemed to validate the quality of the enhanced skill work that they are already doing:

“So, when the opportunity to get a CAC came about, that was really important to me, because I felt that it validated the work that I had done, and it actually gave me the credentials I felt that I probably had worked at. So, that other people would recognize that I knew what I was doing.” (Case 3 Participant 2 CAC, COE)

This validating power was also evident in the experiences described by those practitioners that we interviewed who had made application for the CAC but were ultimately unsuccessful. In these situations, the individuals felt that the decision not to certify their added competence was an indication that the College does not value their enhanced skill work:

“[Having application for a CAC via the leadership route denied] made me feel devalued. I think it made it feel like you’re not doing… [pause]… I’m not the only one. I know there was a colleague of mine that also had the same rejection and actually was told the same kind of thing, that it makes you feel like the work you do is not valued because it’s not in a hospital system. It also makes you feel like well everybody could do what you’re doing so it’s not a big deal.” (Case 6 Participant 3 CAC, COE; application for CAC PC denied)

Barriers to Pursuing a CAC

The interviews with family physicians and trainees also revealed that the motivations to pursue the CAC designation are strongly influenced by the barriers inherent to this pursuit. In this regard, the data reveal how family physicians experience barriers to pursuing additional training once they are embedded in a practice and a community, including the personal and professional cost to leaving one’s practice for training, the lack of coverage for patients, and the impact on their families’ lives:

“I think what makes it challenging for people to go back when they’re out in practice is if you have a family practice, what the heck do you do with your family practice? Then knowing that you’re getting extra skills, what are you planning to do afterwards, and can you continue to meet the demands of that family practice? … Then you have to figure out what your new role is going to be coming back. It’s a lot if you’ve got a family at all. Moving your family just for one year is a big ask, or not moving them and then travelling them back and forth. Changes to income structure as a resident salary is not the same as a working physician’s salary so you have to plan for what that means to your lifestyle and maintaining skills that you’re not practising very often if you want to keep using them afterwards is a challenge.” (Case 4 Participant 1 CAC, PC; CAC, FPA)

In some places, these barriers were addressed in part or in full by provincial and territorial support via formal programs:

“In the territory, if someone goes and does the training, there is supplemental income support for them while they’re away for the time of their training, and also support for them to find locums and things.” (Case 4 Participant 1 CAC [PC] CAC [FPA])

In other instances, enhanced skills training is supported informally by colleagues who recognize the community need:

“We have actually had docs that have practiced for many years and gone back and done the anesthesia program. If there is a need, we have figured out how to make it happen. … In some cases, it was just managing their patient load that they had established for this period of time while they were away. The rest of the group picked them up and took care of them and said we would manage that for them. We, as a clinic, have provided some financial support for them while they have been away.” (Case 2 Participant 10 Administrator)

However, this informal approach was considered untenable in some rural communities where attending extra training would require relocation:

“There are a ton of people on a waitlist for a doctor so there’s no way that any physician here could manage my patients. I have 1,200 patients. Some physicians here, that do more other work at the hospital, only have 500 patients so they can’t take 1,200 of mine and look after them so they would be stuck. I would have to probably figure out a way to get my most sick and complicated patients and spread them out amongst a few people. Then everyone else would probably just have to go to the walk-in.” (Case 2 Participant 9 ES Obstetrics)

Participants across Canada noted their perception that the CAC is a credible marker of enhanced clinical skill. This has several implications. The credibility of the designation influences motivations to pursue the certificate, including for the purposes of enhancing professional identity, validating skills, and securing more favorable work arrangements. Through this conferment of credibility, the CACs have an indirect, or downstream, impact on health care delivery practices above and beyond the direct outcomes of the enhanced-skill work. The certificate is perceived as having the potential to support individuals in negotiations related to hiring, privileging, billing, and funding for programs. It is believed to enhance perceptions of physician expertise or leadership in the field. The impacts on professional identity can also be more intangible, altering a physician’s confidence in their own ability or legitimacy. In this regard, we highlight that the formal relationship between the CFPC and the CACs is the main distinction between CAC holders and those family physicians who provide enhanced skills with non-CAC credentials or without credentials. This association leads to the idea that the College will prioritize advocacy for health systems and hiring practices that favor CAC holders, a perception that influences practicing physician and resident trainee motivations for pursuing the certification. Notably however, we did not identify any such lobby or policy specific to the certificate. Yet, through perceptions of preferential arrangements for CAC holders, the certificate may promote a perceived devaluation of generalist family physicians and enhanced-skill family physicians without the certificate.

By altering perceptions of the expertise of generalist versus CAC family physicians, the certificates also alter perceptions about the types of challenges and rewards a family physician can reasonably expect to encounter through their work within a community. These expectations, in turn, influence the way physicians balance decisions against their personal and professional aspirations. Through this mechanism, the CACs may create some risks for the delivery of comprehensive, community-adaptive health care in Canada. In particular, an increased focus on specialization may serve to erode morale and exacerbate existing challenges associated with upholding the values of generalist family medicine.24-26 That is, the standards for added competence serve to communicate a desired demarcation between comprehensive generalist family medicine skills and additional competence worthy of a CAC. With respect to trainees, this is potentially problematic because it may shift the focus of the professional base away from generalism. Trainees who perceive family medicine to lack prestige may be particularly vulnerable to credentialism.27

To offset these risks, we offer a few recommendations. First, the College should consider ways to ensure that the pursuit of the certificate is tied to prevailing community needs. This may mean developing systems of training that afford family physicians who are established in communities with noted health care needs greater access to gain certification. Given the evidence of the difficulty that midcareer physicians experience with engaging in training, any such system would need to offer support to these individuals that facilitates their education in a way that does not compromise their current practices and livelihoods. Another important recommendation is to develop incentives for generalist practice. Given that accessible primary health care systems that address most personal health care needs in the context of continuous relationships with patients, families, and communities are associated with the most robust and equitable population health outcomes, there is good reason to encourage the work of generalist family physicians who provide services across the full scope of family medicine practice.28

This work is situated within the Canadian context, which stands as a potential limitation to the generalizability of the presented findings to jurisdictions without official certification of subspecialties within generalist family medicine. In this regard, we recognize that the motivations and barriers associated with practice arrangements, remuneration structures, and personal and community tensions described herein reflect uniquely Canadian perspectives. However, we do anticipate that the expressed concerns about the value of peer recognition and the overwhelming nature of full-scope generalist practice will resonate broadly with family physicians across North America and around the world. In this regard, we recommend that the impact and influence of enhanced skill work and credentialing be a key feature of any jurisdictional policy commitment to primary care and family medicine.

As focused practice is increasingly perceived as associated with improved quality of professional life, family physicians may move away from generalist practice, reducing access to comprehensive family medicine for patients. The Canadian CAC, in some instances, is encouraging this migration, yet also has the potential to influence physicians towards community-adaptive comprehensive care. In this regard, the CFPC may advocate for corresponding incentives for generalist practice and incentives for enhanced skill practice that align with pervasive community needs. In the latter case, the CAC designation may serve as one such incentive that has the power to confer a sense of validation to practitioners while also facilitating the way they interact and lobby with local health authorities.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the valuable contributions of the CFPC, and specifically Dr Roy Wyman, Dr Nancy Fowler, Dr Jose Pereira, Tatjana Lozanovska, and Danijela Stojanovska, for their support of this project.

Data Sharing Statement: These data are not available for use by other researchers.

Author Contributions: Authors L.G. and M.V. designed and supervised all aspects of the project. I.A. conducted the interviews and was responsible for data collection and management. L.G., I.A., and M.V. led data analysis and interpretation. L.G. led the writing of the manuscript. All authors participated in data analysis and interpretation and contributed to the critical revision of the paper, approved the final manuscript for publication, and have agreed to be accountable for all aspects of the work in ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Ethics Approval: This work received ethics approved from the Hamilton Integrated Research Ethics Board (HIREB #5151).

Funding Statement: The College of Family Physicians of Canada provided funding for this study.

Prior Presentation: This study was Presented to the College of Family Physicians of Canada on May 25, 2020.

Disclaimer: The views expressed in this article are the authors’ own and not an official position of their institutions or the funder.

References

- Fowler N, Wyman R, eds. Residency Training Profile for Family Medicine and Enhanced Skills Programs Leading to Certificates of Added Competence. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2021.

- Additional Certifications Available to Family Physicians. American Board of Family Medicine. Accessed December 22, 2021. https://www.theabfm.org/added-qualifications

- Vision, Mission, Values, and Goals. College of Family Physicians of Canada. Accessed May 18, 2021. https://www.cfpc.ca/principles

- College of Family Physicians of Canada. A New Vision for Canada: Family Practice—The Patient’s Medical Home 2019. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2019. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://patientsmedicalhome.ca/files/uploads/PMH_VISION2019_ENG_WEB_2.pdf

- College of Family Physicians of Canada. Family Medicine Professional Profile. Mississauga, ON: College of Family Physicians of Canada; 2018. Accessed October 14, 2020. https://portal.cfpc.ca/resourcesdocs/uploadedFiles/About_Us/FM-Professional-Profile.pdf

- Stone D. Policy Paradox. New York: Norton & Company; 2013.

- Lavergne MR, Goldsmith LJ, Grudniewicz A, et al. Practice patterns among early-career primary care (ECPC) physicians and workforce planning implications: protocol for a mixed methods study. BMJ Open. 2019;9(9):e030477. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2019-030477

- Glazer J. Specialization in family medicine education: abandoning our generalist roots. Fam Pract Manag. 2007;14(2):13-15.

- Coutinho AJ, Cochrane A, Stelter K, Phillips RL Jr, Peterson LE. Comparison of intended scope of practice for family medicine residents with reported scope of practice among practicing family physicians. JAMA. 2015;314(22):2364-2372. doi:10.1001/jama.2015.13734

- Dhillon P. Shifting into third gear: current options and controversies in third-year postgraduate family medicine programs in Canada. Can Fam Physician. 2013;59(9):e406-e412.

- Shepherd LG, Burden JK. A survey of one CCFP-EM program’s graduates: their background, intended type of practice and actual practice. CJEM. 2005;7(5):315-320. doi:10.1017/S1481803500014500

- Grierson L, Vanstone M, Allice I. The factors influencing the impacts of the Certificates of Added Competence: A qualitative case study of enhanced skill family medicine practice across Canada. CMAJ. 2021;9:966-972. doi:10.9778/cmajo.20200278

- Bennett KL, Phillips JP, Finding PJP. Finding, recruiting, and sustaining the future primary care physician workforce: a new theoretical model of specialty choice process. Acad Med. 2010;85(10)(suppl):S81-S88. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e3181ed4bae

- Scott I, Wright B, Brenneis F, Brett-Maclean P, McCaffrey L. Why would I choose a career in family medicine?: reflections of medical students at 3 universities. Can Fam Physician. 2007;53(11):1956-1957.

- Connelly MT, Sullivan AM, Peters AS, et al. Variation in predictors of primary care career choice by year and stage of training. J Gen Intern Med. 2003;18(3):159-169. doi:10.1046/j.1525-1497.2003.01208.x

- Kiolbassa K, Miksch A, Hermann K, et al. Becoming a general practitioner--which factors have most impact on career choice of medical students? BMC Fam Pract. 2011;12(1):25. doi:10.1186/1471-2296-12-25

- Scott I, Gowans M, Wright B, Brenneis F, Banner S, Boone J. Determinants of choosing a career in family medicine. CMAJ. 2011;183(1):E1-E8. doi:10.1503/cmaj.091805

- Wright B, Scott I, Woloschuk W, Brenneis F, Bradley J. Career choice of new medical students at three Canadian universities: family medicine versus specialty medicine. CMAJ. 2004;170(13):1920-1924. doi:10.1503/cmaj.1031111

- Yin RK. Applications of case study research. 3rd ed. Sage; 2011.

- Baldwin DWC. Some historical notes on interdisciplinary and interprofessional education and practice in health care in the USA. J Interprof Care. 1996;10(2):173-187. doi:10.3109/13561829609034100

- Goldman J, Meuser J, Rogers J, Lawrie L, Reeves S. Interprofessional collaboration in family health teams: an Ontario-based study. Can Fam Physician. 2010;56(10):e368-e374.

- Meuser J, Bean T, Goldman J, Reeves S. Family health teams: a new Canadian interprofessional initiative. J Interprof Care. 2006;20(4):436-438. doi:10.1080/13561820600874726

- Eisenhardt KM, Graebner ME. Theory building from cases: opportunities and challenges. Acad Manage J. 2007;50(1):25-32. doi:10.5465/amj.2007.24160888

- O’Malley AS, Rich EC. Measuring comprehensiveness of primary care: challenges and opportunities. J Gen Intern Med. 2015;30(3)(suppl 3):S568-S575. doi:10.1007/s11606-015-3300-z

- Beaulieu MD, Rioux M, Rocher G, Samson L, Boucher L. Family practice: professional identity in transition. A case study of family medicine in Canada. Soc Sci Med. 2008;67(7):1153-1163. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.06.019

- Selva Olid A, Zurro AM, Villa JJ, et al; Universidad y Medicina de Familia Research Group (UNIMEDFAM). Medical students’ perceptions and attitudes about family practice: a qualitative research synthesis. BMC Med Educ. 2012;12(1):81. doi:10.1186/1472-6920-12-81

- Rodríguez C, Tellier PP, Bélanger E. Exploring professional identification and reputation of family medicine among medical students: a Canadian case study. Educ Prim Care. 2012;23(3):158-168. doi:10.1080/14739879.2012.11494099

- Starfield B, Shi L, Macinko J. Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. Milbank Q. 2005;83(3):457-502. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x

There are no comments for this article.