Background and Objectives: During the COVID-19 pandemic, medical schools and residencies have utilized electronic learning (e-learning). Factors such as internet access, age, degree of introversion/extroversion, and propensity to adopt new technologies impact attitudes toward e-learning. This study investigates family medicine educators’ satisfaction, effectiveness, and feasibility perceptions of e-learning, characterizes demographic factors impacting attitudes, and identifies which aspects of e-learning are important to educators.

Methods: In fall 2020, a cross-sectional survey via the 2020 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) general membership survey was conducted. Members of CAFM-affiliated associations were invited by email to participate.

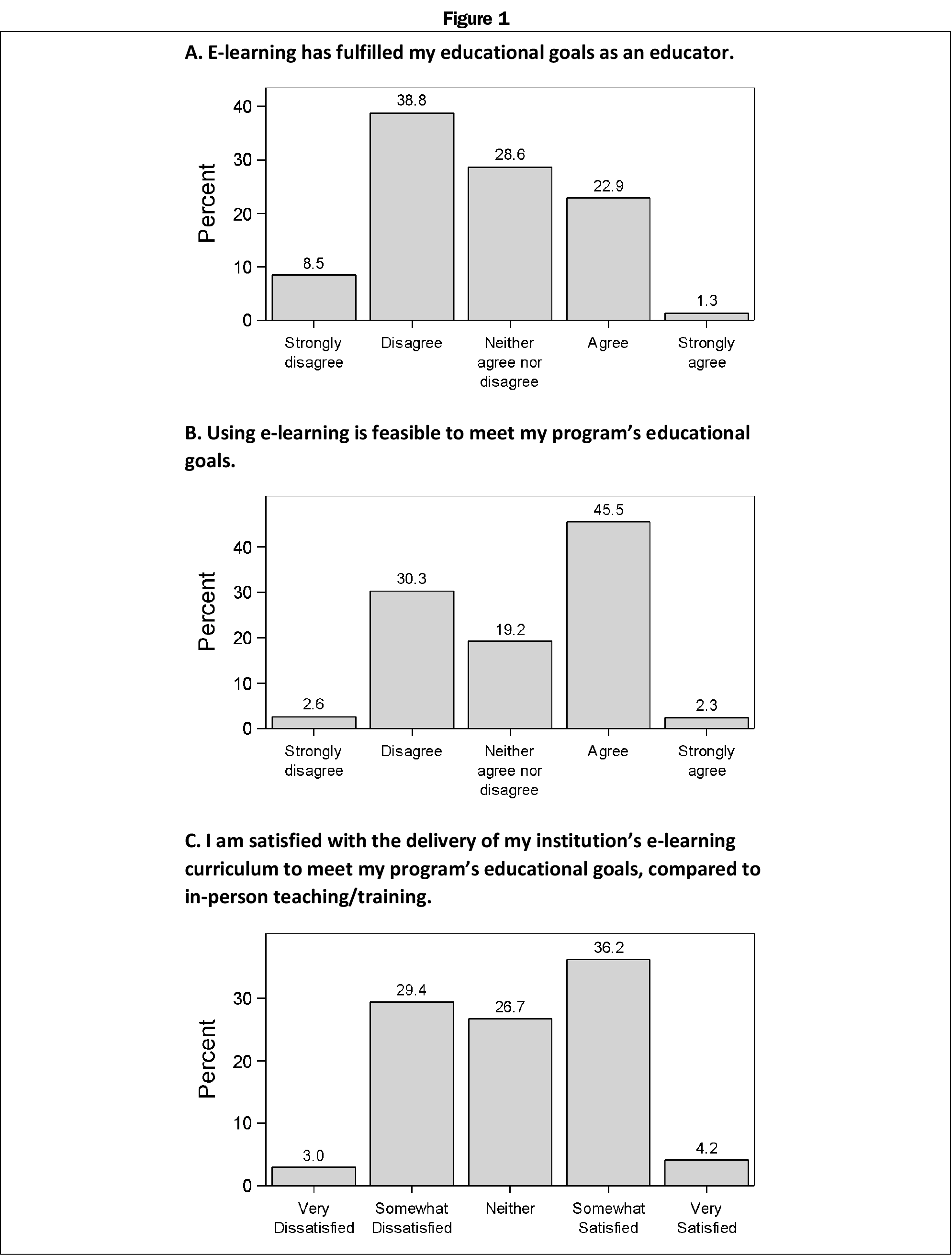

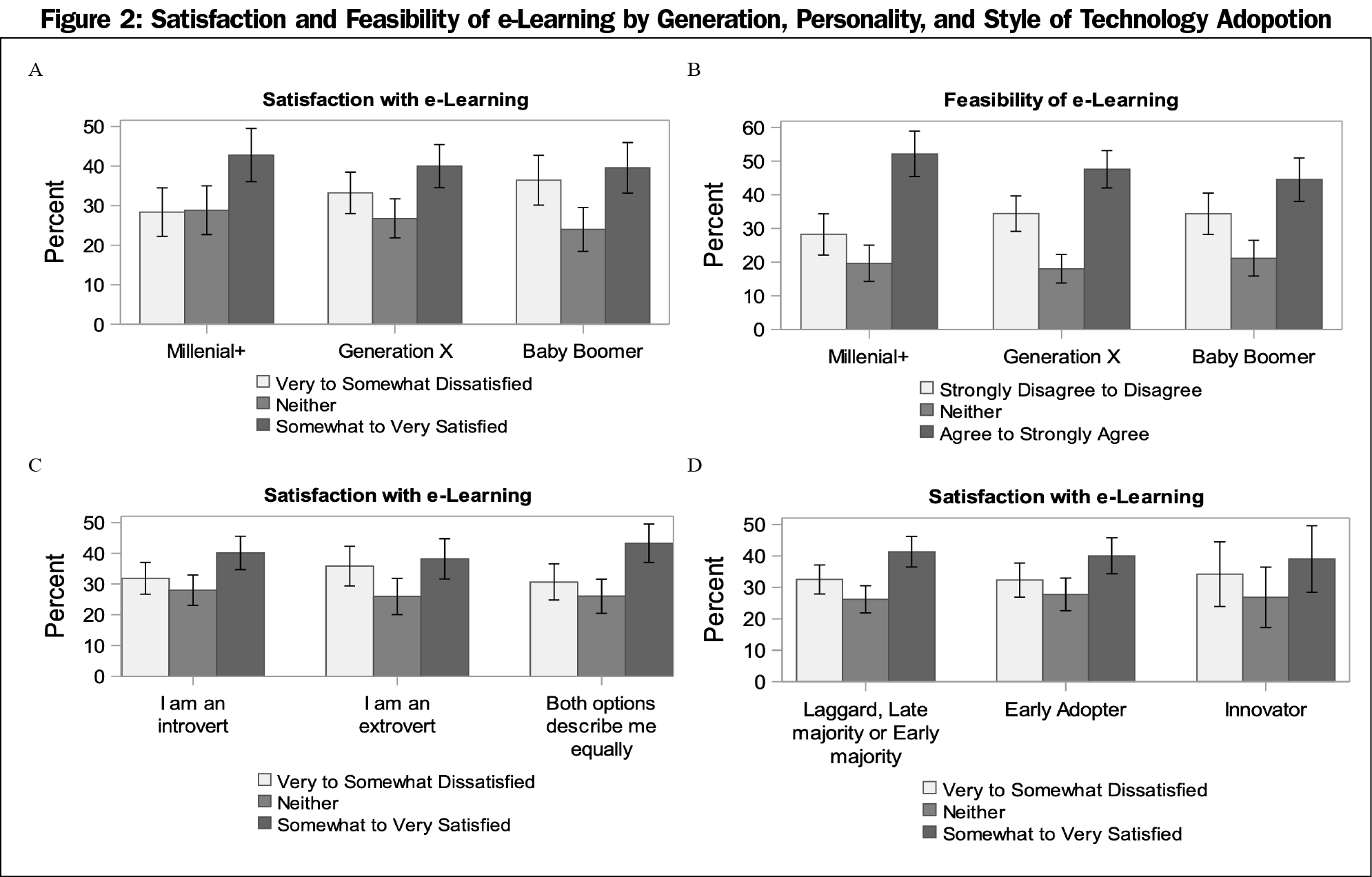

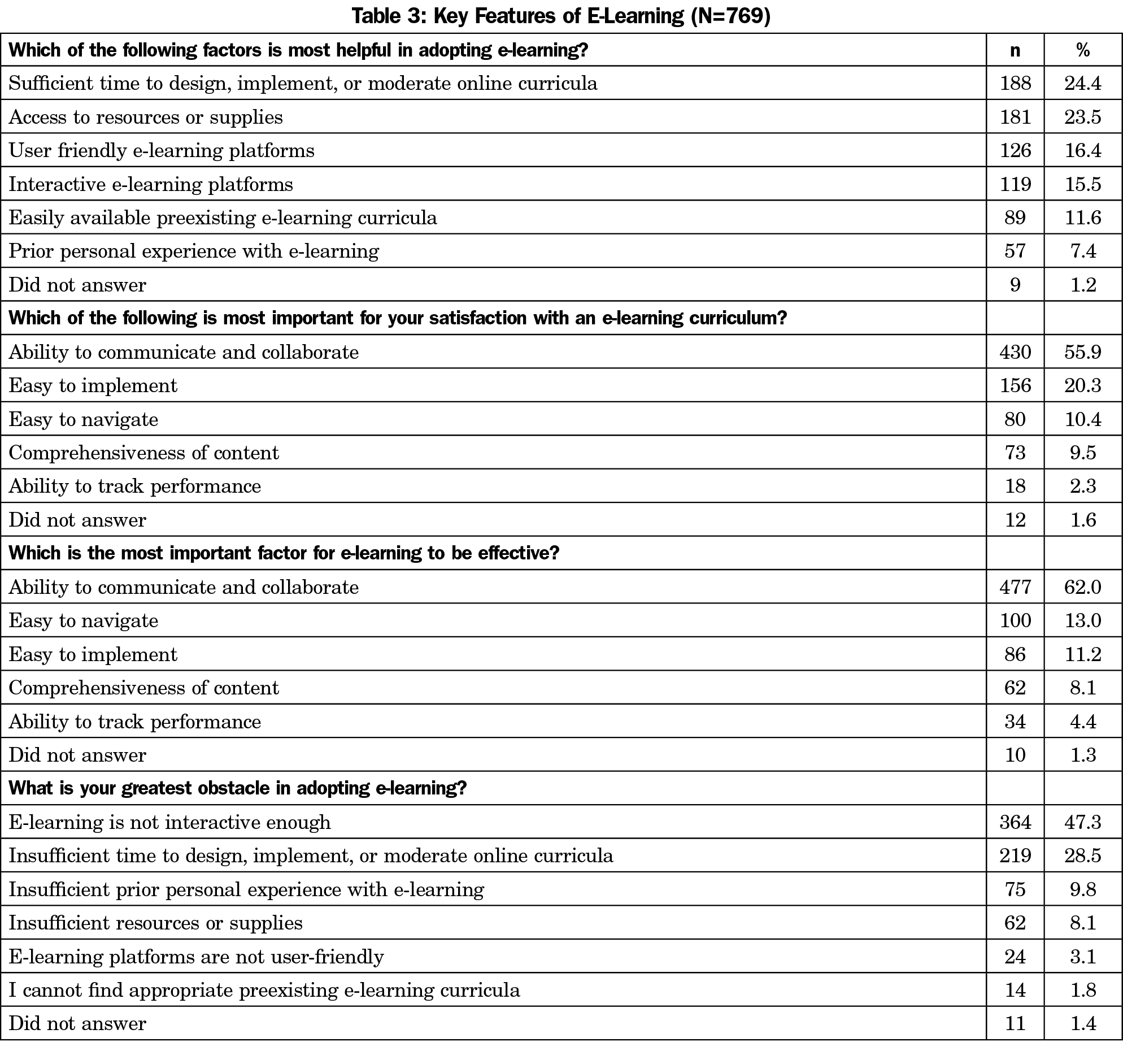

Results: The response rate for the survey was 20.1% (n=862). Of the respondents, 40.4% (n=311) reported satisfaction with e-learning, 47.8% (n=368) found e-learning feasible, and 24.2% (n=186) reported e-learning met their educational goals. No differences were found in satisfaction, feasibility, or effectiveness scores according to generation, introvert/extrovert status, or technology adopter status. Interactive capabilities were the most important factor for e-learning satisfaction (55.9%) and effectiveness (62.0%). Sufficient time was the most frequently selected factor for ease of adoption. Baby Boomer respondents reported platforms not user-friendly, insufficient prior experience as the greatest obstacle more frequently than other generations, and insufficient time less frequently than other generations. Otherwise, rankings of e-learning factors were similar among groups.

Conclusions: Satisfaction with and perceived feasibility and effectiveness of e-learning varies among family medicine educators. No differences were found in satisfaction, feasibility, or effectiveness scores according to generation, introvert/extrovert status, or technology adopter status. Respondents consistently ranked interactive capabilities most important for e-learning satisfaction and effectiveness. More research is needed to compare student and learner perspectives regarding e-learning.

During the COVID-19 pandemic, medical schools and residencies maintained social distancing by using electronic learning (e-learning). E-learning teaches and trains subjects via digital platforms, allowing education to continue despite geographic distance.1-3 E-learning presents challenges to learners and educators, such as technological capability, time and resource barriers, and personal comfort levels with e-learning.4,5 Many e-learning supplements exist, however there are no standardized or comprehensive online family medicine (FM) curricula.

Previous studies indicate both synchronous and asynchronous e-learning are efficacious and acceptable to learners.2,3 Self-study modules are feasible to implement, had better attendance than lectures, had high resident satisfaction scores, and in-training exam scores were comparable to preintervention scores.2 Broadcast versus in-person educational sessions yielded no difference in satisfaction or pre/postsession knowledge scores.3

Multiple factors may affect the e-learning experience. According to Diffusion of Innovation Theory (DOIT), societal adoption of new technology happens gradually, following a bell-shaped curve: innovators adopt new technology first, followed by early adopters, then early majority, late majority, and finally laggards.6 Five factors influence the adoption of novel technology: relative advantage (perceived benefits), compatibility (how well it meets adopters’ needs), complexity (how challenging it is to use), trial ability (the extent to which it can be tested and tried), and observability (the extent to which the innovation provides tangible results).6 Individual factors, such as internet age and degree of introversion/extroversion, also impact attitudes toward e-learning.5 “Digital natives,” who were born in the digital age, use and process information from computer technologies more easily than “Digital immigrants” who learned to use computers during their adult life.7 Experts recommend an extensive design process involving needs assessment, technical development, and testing.8 Seasoned e-learning educators emphasize creativity, flexibility, visual appeal, and consideration of student perspectives.9-11 Experienced online educators caution that successful e-learning curricula require a significant time investment, and the sudden shift to online learning necessitated by COVID-19 may lead to bad impressions of online teaching.9,11

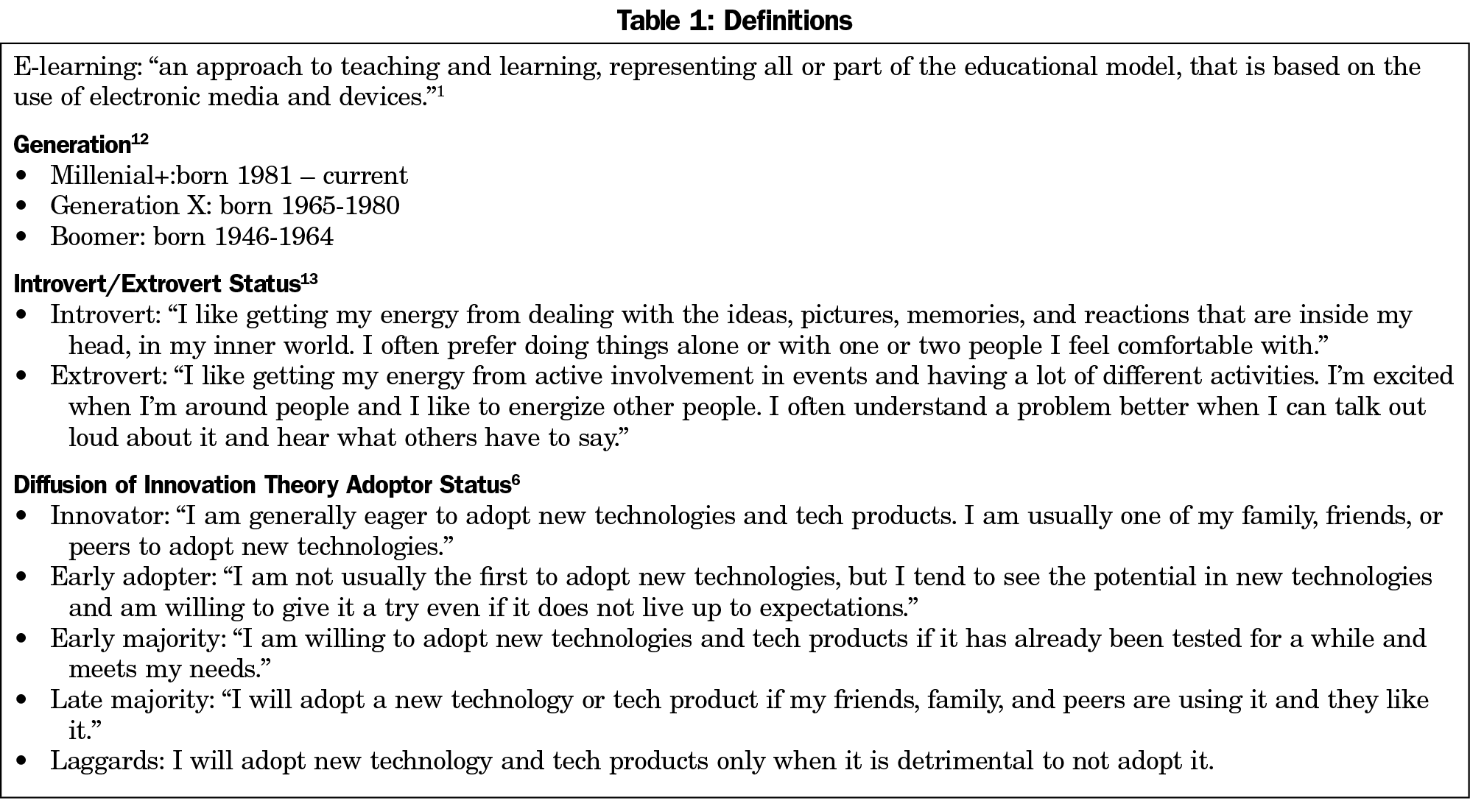

This study investigates family medicine educators’ satisfaction with e-learning and perceptions of e-learning feasibility and effectiveness, characterizes demographic and personality factors which may impact attitudes regarding e-learning, and identifies which aspects of e-learning curricula are most important to educators. We hypothesized (1) Millennial and younger generations (Millenial+) have greater satisfaction with e-learning compared to Generation X (GenX) and Baby Boomers (Boomers), (2) Millennial+ perceive greater feasibility of e-learning compared to GenX and Boomers, (3) Introverts have increased satisfaction with e-learning compared to extroverts, (4) innovators and early adopters have greater satisfaction with e-learning, and (5) family medicine educators value ease of use above content, visual appeal, or other aspects of e-learning curricula. Definitions of groups are shown in Table 1.

This cross-sectional survey utilized data from the Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) general membership survey of family medicine educators between November 20, 2020, and December 15, 2020. Invited participants were members of CAFM organizations (Society of Teachers of Family Medicine, North American Primary Care Research Group, Association of Departments of Family Medicine, and Association of Family Medicine Residency Directors). The survey excluded program directors, clerkship directors, and department chairs. Qualifying participants were sent an email invitation and a SurveyMonkey link. Nonrespondents received four participation requests to complete the survey, the final request at 2 days before closing the survey. The survey was distributed to 4,582 candidates. Of these, 177 were returned as undeliverable email addresses and 58 were excluded who had previously opted out of receiving surveys from SurveyMonkey. Additionally, 64 respondents did not meet the qualifying questions and were excluded from further survey questions. The survey was delivered to a final sample of 4,283 family medicine physicians (4,133 US and 215 Canada).

We calculated frequencies and percentages for subgroups and continuous variables and summarized using means and standard deviations. We used χ2 tests and Fisher’s exact tests to compare distributions of categorical variables. We used analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used to test whether continuous variables varied by subgroup. We used Sidak’s procedure for multiple comparisons to compare means among subgroups. We used nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis tests to evaluate whether ANOVA results were sensitive to potential violations of analysis assumptions. Selected covariates were dichotomized and analyzed by logistic regression. Odds ratios and 95% confidence intervals are reported for those analyses.

The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved the study in November 2020.

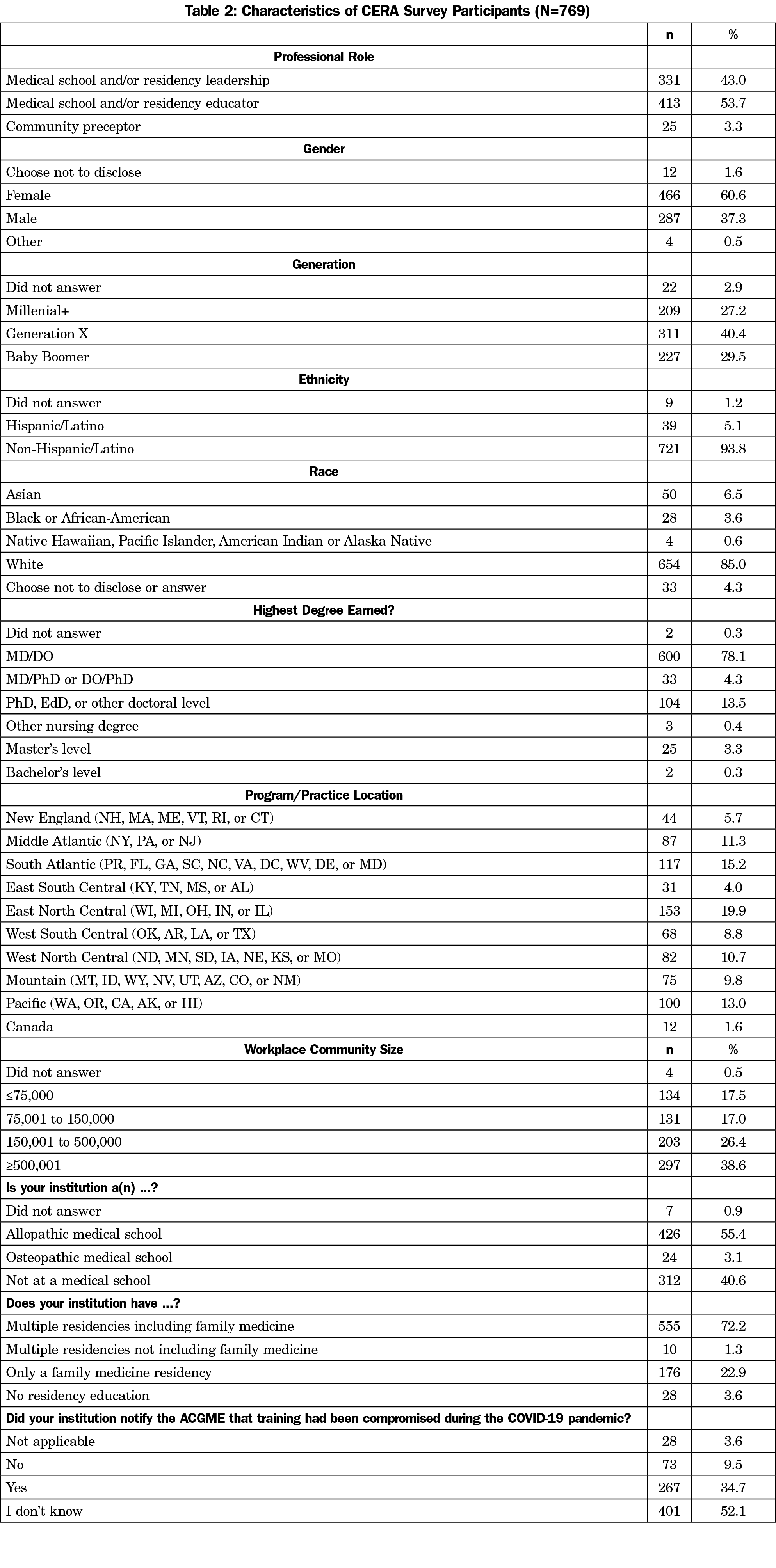

The overall response rate for the survey was 20.1% (n=862/4,283). Ninety-three respondents were excluded because 82 dropped out of the survey before our first question, six did not answer a question about percent time in e-learning, and five skipped the majority of our questions. The remaining (n=769) answered both our first and last questions. Demographic characteristics of respondents are summarized in Table 2. The demographics of our cohort are similar to the sampling cohort, except for a larger White population (85% to 69%). Respondents reported a median of <33% of their time on e-learning prior to the COVID-19 pandemic and reported no significant change in GME/UME education, research, clinical practice, or service obligations during the COVID-19 pandemic.

Overall perceptions of satisfaction and feasibility of e-learning are summarized in Figure 1. There was no difference in satisfaction scores between Millenial+, Generation X, or Baby Boomers (P=.211). Compared to Millenial+, there was no difference in combined “Somewhat Satisfied/Very Satisfied” responses among Baby Boomers (n=743, OR 0.87 [95% CI 0.60,1.28], P=.495) or Gen X respondents (OR 0.89 [95% CI 0.62,1.27], P=.527; Figure 2A). Similarly, when asked “Using e-learning is feasible to meet my program’s educational goals,” no difference was seen in combined “Agree/Strongly Agree” responses for Millenial+ vs Baby Boomers (N=743, OR 0.74, [95% CI 0.50, 1.07], P=.110) or Millenial+ vs Gen X respondents (OR 0.83 [95% CI 0.59, 1.18], P=.308; Figure 2B). Compared to extroverts, there were no differences in combined “Somewhat Satisfied/Very Satisfied” responses for introverts (N=747, OR 1.08 [95% CI 0.76, 1.55], P=.658) or respondents identifying as equally introverted and extroverted (OR 1.23, [95% CI 0.85, 1.80] P=.275; Figure 2C). No differences were seen regarding DOIT adopter status (N=764). Compared to aggregated laggard, late majority, and early majority respondents, there were no differences in combined “Somewhat Satisfied/Very Satisfied” responses for early adopters (N=764, OR 0.95 [95% CI 0.69, 1.29], P=.731) or innovators (OR 0.91 [95% CI 0.56, 1.48], P=.703; Figure 2D).

Perceptions of key features of e-learning and obstacles to using e-learning are summarized in Table 3. We observed similar responses among the groups in which e-learning features are most important. Millenial+ vs GenX vs Boomer responses were not significantly different for the questions “Which of the following factors is most helpful in adopting e-learning?” (P=.439, Fisher’s exact test), “Which of the following is most important for your satisfaction with an e-learning curriculum” (P=.345); or “Which is the most important factor for e-learning to be effective?” (P=.887).

We observed some differences between generational cohorts regarding “What is your greatest obstacle in adopting e-learning” (P=.001, Fisher’s Exact Test). Boomers selected “platforms not user-friendly” (6.2%) more frequently than Millennial+ (2.4%) and GenX (1.3%). Boomers selected “insufficient prior experience” (14.1%) more frequently than Millenial+ (7.7%) or GenX (8.0%). Boomers selected “insufficient time” (22%) less frequently than Millenial+ (30.1%) and GenX (32.2%).

No differences were seen among the DOIT adopter status groups with respect to most helpful feature (P=.296), most important for satisfaction (P=.537), most important factor to be effective (P=.391), or regarding greatest obstacle to implement (P=.193).

E-learning use was increasing prior to COVID-19 and was integral to medical training during COVID-19.10 However, there is limited information regarding its use and effectiveness in family medicine education. Less than half of survey respondents were satisfied with e-learning, agreed that e-learning is feasible, or agreed that e-learning met their educational goals. We found no differences in satisfaction or perceived feasibility among generational cohorts, introvert/extroverts, or DOIT adopter groups. All groups similarly reported the ability to communicate and collaborate as being most important for e-learning satisfaction and effectiveness. Further investigation may elucidate whether to prioritize collaboration among learners, among faculty, or between learners and educators.

Negative perceptions of e-learning may be due to a variety of factors. Groups reported sufficient time and resources as most important to adopting e-learning. Though poor satisfaction scores in this survey may reflect the sudden mandatory pivot to e-learning due to the unforeseen COVID-19 pandemic, faculty in a qualitative study reported online curricula required more time than live lectures.14 Educator satisfaction and perceived feasibility may increase if given ample time, resources, and training.

Recent studies of students and faculty have highlighted the importance of interactive capabilities for successful e-learning.14, 15 Similarly, our survey respondents cited lack of interactive capabilities as the most significant obstacle in adoption. This frustration may reflect inherent limitations of e-learning, or indicate the need for increased training or further development of e-learning platforms.

Negative perceptions of e-learning may be even more pronounced for students and residents. A 2021 survey of medical students and educators assessed perceptions and effectiveness of online medical curricula developed in response to COVID-19 pandemic shutdowns. It found that fewer students than educators found e-learning equivalent or superior to face-to-face learning (33% vs. 51%), and more students than instructors reported increased difficulties with e-learning (69% vs 51%).16 Technological and connectivity barriers were frequently cited as barriers, highlighting potential disparities in learning access depending on resources available to off-campus learners. Sixty-seven percent of students reported fatigue and losing interest with e-learning, which supports our findings regarding the importance of interactive capabilities.

This study has several limitations. Survey respondents may be more likely to feel comfortable with online technology than nonrespondents. Some respondents skipped questions, limiting interpretation of these respondents’ perspectives. Furthermore, the survey was exclusively distributed to family medicine educators. It is possible that few differences were found in this survey because the individuals surveyed represent a homogenous group despite differences in age or personality factors. It is also possible that the rapid shift to e-learning programs during the COVID-19 pandemic may not accurately reflect e-learning attitudes if given sufficient time and resources to craft a curriculum. Nonetheless, leadership in medical schools and residency programs can use these findings to maximize e-learning curricula, such as investing in platforms with interactive capabilities and providing sufficient time for course design and upkeep.

E-learning use was increasing prior to COVID-19, was the primary means of medical training during COVID-19, and will likely continue to increase in the future.10 To our knowledge, this survey is the first large, international survey of family medicine educators regarding e-learning experience. More research is needed to compare the e-learning experience between educators, medical students, and residents, and identify which features are most important to highly-skilled adult learners.

This survey of family medicine educators found a wide range of satisfaction, perceived feasibility, and perceived effectiveness of e-learning for medical education. No differences were found in satisfaction, feasibility, or effectiveness scores according to generation, introvert/extrovert status, or DOIT adopter status. Respondents consistently ranked interactive capabilities as the most important factor for e-learning satisfaction and effectiveness. This large international study was sufficiently powered to detect small differences between demographic comparison groups, when differences existed. It is limited by reflecting only family medicine educators’ perspectives. More study is needed to elucidate perspectives regarding e-learning among students, residents, and other medical providers.

Acknowledgments

Presentations: This study was presented in poster format at the 2021 Society of Teachers of Family Medicine Virtual Annual Spring Conference.

References

- de Leeuw RA, Logger DN, Westerman M, Bretschneider J, Plomp M, Scheele F. Influencing factors in the implementation of postgraduate medical e-learning: a thematic analysis. BMC Med Educ. 2019;19(1):300. doi:10.1186/s12909-019-1720-x

- Kornegay JG, Leone KA, Wallner C, Hansen M, Yarris LM. Development and implementation of an asynchronous emergency medicine residency curriculum using a web-based platform. Intern Emerg Med. 2016;11(8):1115-1120. doi:10.1007/s11739-016-1418-6

- Markova T, Roth LM, Monsur J. Synchronous distance learning as an effective and feasible method for delivering residency didactics. Fam Med. 2005;37(8):570-575.

- Schifferdecker KE, Berman NB, Fall LH, Fischer MR. Adoption of computer-assisted learning in medical education: the educators’ perspective. Med Educ. 2012;46(11):1063-1073. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2012.04350.x

- Luo L, Cheng X, Wang S, et al. Blended learning with Moodle in medical statistics: an assessment of knowledge, attitudes and practices relating to e-learning. BMC Med Educ. 2017;17(1):170. doi:10.1186/s12909-017-1009-x

- LaMorte WW. Diffusion of Innovation Theory. Boston University School of Public Health. Behavioral Change Models. Accessed July 20, 2021. https://sphweb.bumc.bu.edu/otlt/MPH-Modules/SB/BehavioralChangeTheories/BehavioralChangeTheories4.html

- Prensky M. Digital natives, digital immigrants. On Horiz. 2001;9(5):1-6. doi:10.1108/10748120110424816

- Minasian-Batmanian LC. Guidelines for developing an online learning strategy for your subject. Med Teach. 2002;24(6):645-647. doi:10.1080/0142159021000063998

- Miller MD. Going online in a hurry: What to do and where to start. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Published March 9, 2020. Accessed July 20, 2021. https://www.chronicle.com/article/Going-Online-in-a-Hurry-What/248207

- Darby F. How to be a better online teacher. The Chronicle of Higher Education. April 17, 2019. Accessed July 20, 2021. https://www.chronicle.com/article/how-to-be-a-better-online-teacher/

- Gannon K. 4 lessons from moving a face-to-face course online. The Chronicle of Higher Education. Published March 24, 2019. Accessed July 20, 2021. https://www.chronicle.com/article/4-lessons-from-moving-a-face-to-face-course-online/

- CNN Editorial Research. American generation fast facts. CNN. Published April 19, 2021. Accessed July 20, 2021.https://www.cnn.com/2013/11/06/us/baby-boomer-generation-fast-facts/index.html

- The Myers & Briggs Foundation. Extraversion or Introversion. MBTI Basics. Published 2020. Accessed July 20, 2021. https://www.myersbriggs.org/my-mbti-personality-type/mbti-basics/extraversion-or-introversion.htm?bhcp=1

- Hayat AA, Keshavarzi MH, Zare S, et al. Challenges and opportunities from the COVID-19 pandemic in medical education: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2021;21(1):247. doi:10.1186/s12909-021-02682-z

- Motte-Signoret E, Labbé A, Benoist G, Linglart A, Gajdos V, Lapillonne A. Perception of medical education by learners and teachers during the COVID-19 pandemic: a cross-sectional survey of online teaching. Med Educ Online. 2021;26(1):1919042. doi:10.1080/10872981.2021.1919042

- Tuma F, Nassar AK, Kamel MK, Knowlton LM, Jawad NK. Students and faculty perception of distance medical education outcomes in resource-constrained system during COVID-19 pandemic. A cross-sectional study. Ann Med Surg (Lond). 2021;62:377-382. doi:10.1016/j.amsu.2021.01.073

There are no comments for this article.