Background and Objectives: Medical educators and researchers have increasingly sought to embed online educational modalities into graduate medical education, albeit with limited empirical evidence of how trainees perceive the value and experience of online learning in this context. The purpose of this study was to explore the experiences of hybrid learning in a graduate research methods course in a family medicine and primary care research graduate program.

Methods: This qualitative description study recruited 28 graduate students during the fall 2016 academic term. Data sources included qualitative group discussions and a 76-item online survey collected between March and September 2017. We used thematic analysis and descriptive statistics to analyze each data set.

Results: Nine students took part in three group discussions, and completed an online survey. While students reported positive learning experiences overall, those attending virtually struggled with the synchronous elements of the hybrid model. Virtual students reported developing research skills not offered through courses at their home institution, and students attending the course in person benefited from the diverse perspectives of distance learners. All stressed the need to foster a sense of community.

Conclusions: Quality delivery of online graduate education in family medicine research requires optimizing social exchanges among virtual and in-person learners, ensuring equitable engagement among all students, and leveraging the unique tools afforded by online platforms to create a shared sense of a learning community.

Distance models of instruction became the dominant mode of course delivery when the COVID-19 pandemic forced virtual learning for health professions and other trainees in medicine.1,2 Hybrid e-learning brings in-person and virtual students together in one synchronous learning environment.3,4 While there is a need for evaluative assessment of e-learning across health professions,5 research on how to integrate virtual learning with existing pedagogical approaches remains especially underdeveloped in family medicine.6-8

This brief report explores a 2016 synchronous hybrid learning initiative in a family medicine research training program—termed HyFlex,9 this educational modality has increased its popularity following the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic.10 We aimed to explore how virtual and in-person learners perceived their learning experience, and their suggestions for improvement.

Research Design and Setting

We conducted a qualitative description study11 of HyFlex learning experiences following a three-credit family medicine graduate course in qualitative research. The course was delivered in person to students in Montreal and virtually to students in Switzerland using the Zoom videoconferencing platform. The 3-month course involved 3 hours of weekly instruction, including interactive activities, as well as prelecture quizzes completed asynchronously.12 The McGill University Institutional Review Board reviewed and granted ethics approval for this study (A03-E24-17B).

Participants

All 28 enrolled students (22 in-person, six virtual) were invited to participate after final grades were submitted.

Data Collection

First author (C.R.) facilitated three focus groups13 with students between March and June 2017: two in Canada in English, and one in Switzerland in French. The interview guideline is provided in Appendix 1. Focus groups, the main source of qualitative data, were complemented with an online survey based on the Community of Inquiry Instrument (COI)14-15 and the Online Learning/Distance Education Questionnaire, which was applied between July and September 2017. We decided to triangulate data from focus groups and surveys to better assess three interrelated elements of the HyFlex learning experience, namely social cohesion, cognitive learning outcomes, and teaching quality.

Data Analysis

We applied an inductive, semantic thematic analysis16 to the focus group data according to Braun and Clarke.16 Focus groups were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim. The first author generated initial codes using the ATLAS.ti software. Codes were then discussed and refined through exchanges with the co-authors before applying the consensus codebook to the remaining qualitative dataset. We calculated basic descriptive statistics (medians, averages) from the survey data.

Four virtual students (67%) and five in-person students (23%) consented to participate in 2-hour focus groups that took place in both Montreal and Lausanne.

Theme 1: Positively-Perceived Learning Experience

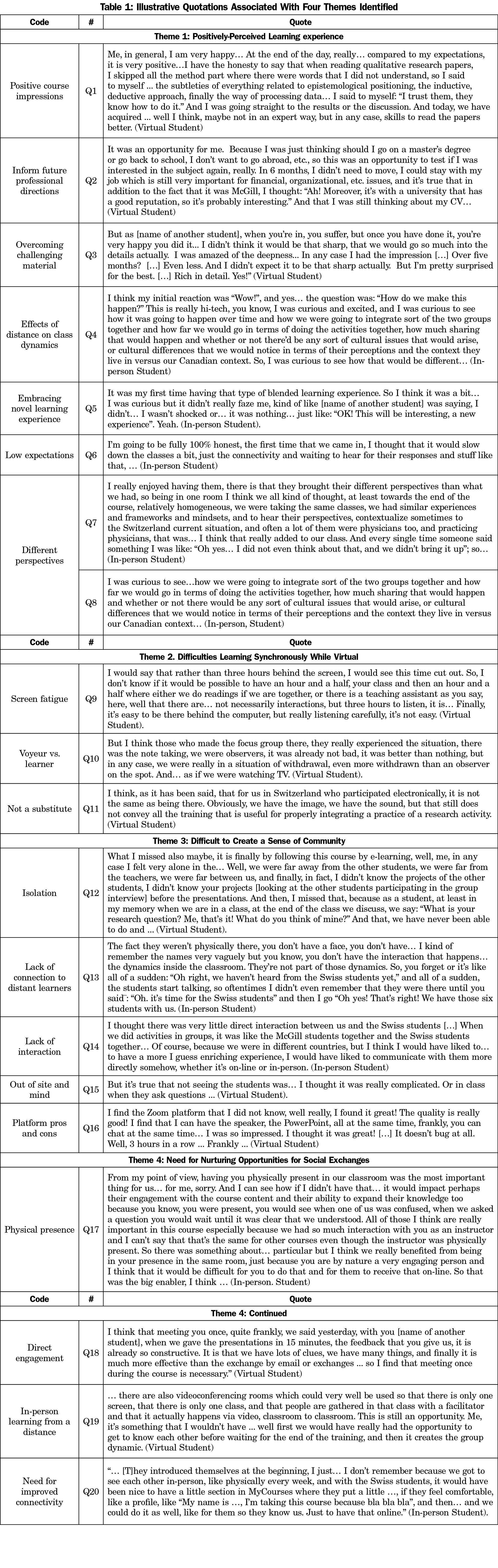

Students expressed satisfaction with the HyFlex learning experience overall (Question [Q]1). Virtual students greatly appreciated the convenience of hybrid learning (Q2 and Q3) and the ability to enroll in a graduate course not otherwise available at their home institution. Most in-person students were motivated by the HyFlex model (Q4 and Q5) despite some apprehension at the start of the course about the quality of the learning experience (Q6). All students found that engaging with virtual peers during open class discussions was especially enriching because they brought “a different perspective” to the discussion (Q7 and Q8).

Theme 2: Difficulties Learning Synchronously While Virtual

Students who attended the course virtually reported that synchronous learning proved challenging given the length and duration of the course (3-hour weekly sessions over almost 4 months) and the time difference contributed to screen fatigue (Q9). Some students reported feeling more like “observers” than active participants during in-class group exercises (Q10 and Q11).

Theme 3: Difficult to Create a Sense of Community

Whereas virtual students felt isolation (Q12), all students lamented the lack of togetherness (Q13 and Q14). In-person learners, in particular, reported greater disconnect when virtual students turned off their webcams (Q15), but nonetheless appreciated diversity and quality of social interactions the Zoom platform afforded (Q16).

Theme 4: Need for Nurturing Opportunities for Social Exchanges

Q17 illustrates how the instructor’s physical presence greatly influenced the quality of the learning experience for in-person students and highlighted the need to improve the quality of these exchanges in the virtual setting. Virtual students likewise emphasized how important direct engagement is to the quality of learning experience (Q18). In addition to the instructor’s physical presence, the need for more frequent and better-quality exchanges was unanimously identified as an area for improvement. Virtual learners suggested gathering during the synchronous online sessions (Q19), whereas in-person students recommended making more use of the learning management system to enhance virtual exchanges (Q20).

Nine students (89% female, 66.7% in-person) consented to participate in the online survey (response rate 32%). Six students reported attending sessions “in-person all the time,” one attended “in-person most of the time” (11.1%), and two attended virtually “most of the time.” Survey responses corroborated findings from the focus groups, notably an overall satisfaction with the course but limited perceived interactions with others. Moreover, most respondents reported having a positive attitude toward the use of computers, felt comfortable and extremely competent working with the video conferencing technology, and appreciated the HyFlex learning environment. Appendix 2 includes a detailed summary of all survey results.

E-learning experiences in family medicine education have been reported in postgraduate education17 and continuing professional development,18 but thus far there has been no reports concerning HyFlex learning experiences. Both in-person and virtual students considered the experience worthwhile, and our findings suggest there is a perceived value-add for HyFlex modalities in family medicine and primary care research training. This study therefore integrates the current body of knowledge that highlights the benefits of e-learning and other virtual learning in relation to traditional modes of teaching and learning in medical education.19,20

Challenges associated with the instructional and learning processes of this educational experience were particularly acute among virtual students, who reported feeling isolated from the instructor and their in-person classmates. Indeed, some in-person students were concerned with how students attending virtually would affect in-class dynamics. Our experiences support the findings of others that fostering a sense of community is critical to the effectiveness of all learning environments.21-24 This could be attained, for instance, if virtual learners gathered in a shared space with a local teaching assistant during the synchronous session. Working with the course instructor, the virtual teaching assistant could coordinate in-class activities, diversifying content delivery using both didactic and interactive approaches. Also, distance learners could remain on webcam for the duration of the session to enhance togetherness and facilitate more fluid engagement. Additionally, the local presence of the course instructor at least once at the end of the course would facilitate in-person feedback, something considered paramount as a capstone to the hybrid learning experience reported here.

In summary, our findings highlight that to better sustain hybrid learning experiences, (i) social exchanges among virtual and in-person learners should be maximized; (ii) the instructor should engage with virtual students several times during the course to exchange and provide feedback in-person; and (iii) the various capacities afforded by online platforms to create a shared sense of a learning community should be optimized.

The COVID-19 pandemic brought about a swift and immediate change to course delivery including for graduate medical instruction. The pandemic likewise motivated institutions to discover innovated ways to combine the strengths of in-person learning with those of virtual learning and carved a new empirical agenda for evaluating the effectiveness of new hybrid models going forward.25 Our findings unveil the complexities of offering high-quality courses in hybrid learning environments in graduate medical education ahead of their more widespread adoption and provide insights for how to effectively prepare instructors for such changes.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the 28 graduate students who participated in the hybrid attendance initiative, particularly those who also participated in its assessment.

Presentations: This study was presented as a poster in the Work in Progress section at the North America Primary Care Research Group (NAPCRG) 45th Annual Meeting in Montreal, Quebec, Canada, November 17-21, 2017.

Author Contribution Statement: Author C.R. instructed the course, wrote the research proposal, conducted fieldwork, and led data analysis and interpretation. V.R. served as the teaching assistant in the course, managed the Zoom platform during the sessions, contributed to the development of the research proposal as well as results interpretation. G.B., in her capacity as Director of the McGill Family Medicine Graduate Programs and Research Divisions, supported the experience in-person during her 2016-2017 sabbatical at the École de Santé publique de Lausanne. T.C. advised V.R. in the use of the Zoom platform during the sessions as education lead of the McGill Family Medicine Innovation in Learning (FMIL), collaborated with CR in fieldwork and data analysis, and led the presentation of a poster at the 2017 NAPCRG 45th Annual Meeting. C.R. and V.R. drafted the manuscript, and T.C. and G.B. contributed to its final version.

Conflict Disclosure: Related to the coauthors’ roles when this hybrid attendance learning experience took place, C.R. was the instructor of the course, V.R. was teaching assistant, G.B. was director of family medicine graduate programs, and T.C. was education lead at the FMIL.

References

- Tabatabai S. COVID-19 impact and virtual medical education. J Adv Med Educ Prof. 2020;8(3):140-143. doi:10.30476/jamp.2020.86070.1213

- Pokhrel S, Chhetri R. A literature review on impact of COVID-19 pandemic on teaching and learning. Higher Education for the Future. 2021;8(1):133-141. doi:10.1177/2347631120983481

- Martin F, Parker MA. Use of synchronous virtual classrooms: why, who, and how? JOLT – MERLOT. 2014;10(2):192-210.

- Goodyear P. Design and co-configuration for hybrid learning: theorizing the practices of learning space design. Br J Educ Technol. 2020;61(4):1045-1060. doi:10.1111/bjet.12925

- Liu Q, Peng W, Zhang F, Hu R, Li Y, Yan W. The effectiveness of blended learning in health professions: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18(1):e2. doi:10.2196/jmir.4807

- Rodríguez C, Bartlett-Esquilant G, Boillat M, et al. Manifesto for family medicine educational research. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61(9):745-747, e398-e400.

- Webster F, Krueger P, MacDonald H, et al. A scoping review of medical education research in family medicine. BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):79. doi:10.1186/s12909-015-0350-1

- Grierson L, Vanstone M. The rich potential for education research in family medicine and general practice. Adv Health Sci Educ Theory Pract. 2021;26(2):753-763. doi:10.1007/s10459-020-09994-7

- Beatty B. Transitioning to an online world: Using HyFlex courses to bridge the gap. In C. Montgomerie & J. Seale (Eds.), Proceedings of ED-MEDIA 2007—World Conference on Educational Multimedia, Hypermedia & Telecommunications (pp. 2701-2706). Vancouver, Canada: Association for the Advancement of Computing in Education (AACE). Accessed October 31, 2021. https://www.learntechlib.org/p/25752

- Kohnke L, Moorhouse BL. Adopting HyFlex in higher education in response to COVID-10: students’ perspectives. Open Learn. 2021;36(3):231-244. doi:10.1080/02680513.2021.1906641

- Sandelowski M. Whatever happened to qualitative description? Res Nurs Health. 2000;23(4):334-340. doi:10.1002/1098-240X(200008)23:43.0.CO;2-G

- Brightspace Software. Kitchener, Ontario, Canada: Desire2Learn. https://www.d2l.com/corporate/products/

- Morgan DL, Ataie J, Carder P, Hoffman K. Introducing dyadic interviews as a method for collecting qualitative data. Qual Health Res. 2013;23(9):1276-1284. doi:10.1177/1049732313501889

- Arbaugh JB, Cleveland-Innes M, Diaz SR, et al. Developing a community of inquiry instrument: testing a measure of the Community of Inquiry framework using a multi-institutional sample. Internet High Educ. 2008;11(3-4):133-136. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2008.06.003

- Swan KP, Richardson JC, Ice P, Garrison DR, Cleveland-Innes M, Arbaugh JB. Validating a measurement tool of presence in online communities of inquiry. e-mentor. 2008;2(24).

- Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res Psychol. 2006;3(2):77-101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Salim H, Lee PY, Ghazali SS, et al. Perceptions toward a pilot project on blended learning in Malaysian family medicine postgraduate training: a qualitative study. BMC Med Educ. 2018;18(1):206. doi:10.1186/s12909-018-1315-y

- Te Pas E, Meinema JG, Visser MRM, van Dijk N. Blended learning in CME: the perception of GP trainers. Educ Prim Care. 2016;27(3):217-224. doi:10.1080/14739879.2016.1163025

- Mens B, Toyama Y, Murphy R, Baki M. The effectiveness of online and Blended Learning: a meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Teach Coll Rec. 2013;115(3):1-47. doi:10.1177/016146811311500307

- Vallée A, Blacher J, Cariou A, Sorbets E. Blended learning compared to traditional learning in medical education: systematic review and meta-analysis. J Med Internet Res. 2020;22(8):e16504. doi:10.2196/16504

- Joyner SA, Fuller MB, Holzweiss PC, Henderson S, Young R. The importance of student-instructor connections in graduate level online courses. JOLT. 2014;10(3):436-445.

- Colpitts BDF, Usick BL, Eaton SE. Doctoral student reflections of blended learning before and during covid-19. JCETR. 2020;4(2):S3-S11.

- Chen BH, Chiou HH. Learning style, sense of community and learning effectiveness in hybrid learning environment. Interact Learn Environ. 2014;22(4):485-496. doi:10.1080/10494820.2012.680971

- Saleh A, Bista K. Examining factors impacting online survey response rates in educational research: perceptions of graduate students. JMDE. 2017;13(29):63-74.

- Garrison DR, Anderson T, Archer W. The first decade of the community of inquiry framework: a retrospective. Internet High Educ. 2010;13(1-2):5-9. doi:10.1016/j.iheduc.2009.10.003

There are no comments for this article.