The importance of evaluating competencies in physician education has been prioritized over the last decade by academic governing bodies. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has worked to establish milestones1 to ensure uniform educational standards in graduate medical education. The need for a standardized approach to guide training and progression of academic medicine teachers as they pursue career advancement has been addressed by others as well.2-5 The purpose of this study was to develop an objective set of criteria for levels of development in each area of competency to help guide academicians in scholarly activity and faculty development.

BRIEF REPORTS

Milestones as a Faculty Development Tool for Career Academic Physicians

Rebecca K. Kemmet, MD | Gregory H. Blake, MD, MPH | Robert E. Heidel, PhD | G. Anthony Wilson, MD

Fam Med. 2022;54(3):207-212.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2022.700483

Background and Objectives: The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has implemented milestones for progression of residents. Career academic physicians would benefit from similar concrete guidance for scholarly activity and faculty development. After developing milestones across six recognized competencies among our family medicine academicians, we acknowledged the potential benefit of expanding the development of milestones throughout the academic medical center.

Methods: Milestones that we previously developed were modified by departmental leaders within our institution reflecting levels of career development based on benchmarks in each field. These objective measures for guiding maturation of clinical and academic skill sets were then circulated to clinicians in five residency programs throughout our academic medical center for self-evaluation. We analyzed the completed surveys to determine if an association exists between years in academics and rank across each area of competency.

Results: We received 53 responses from the 91 faculty invited. We noted a significant association in the competency of medical knowledge with progression from assistant to full professor, and we noted a trend toward significance in professionalism and progression from assistant to full professor. These objective measures of clinician development and competency suggest association with levels of academic career development by rank within the institution.

Conclusions: This rubric can be helpful for directing faculty development and faculty mentorship. These milestones are general enough that other physician specialties may be able to adopt them for their own needs.

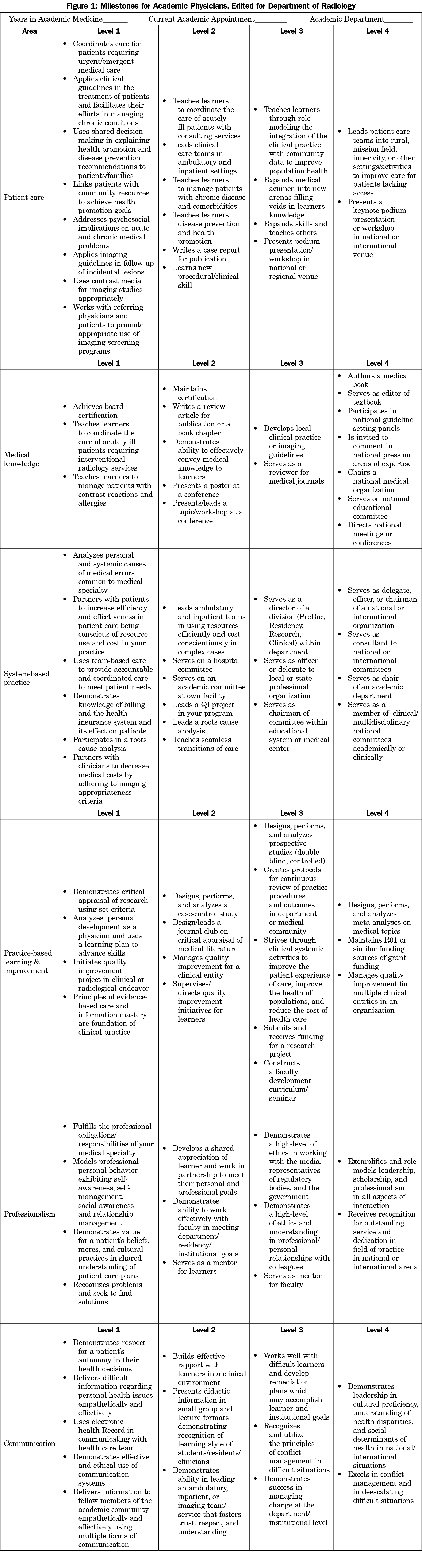

We chose to model the educational milestones created by the ACGME to develop milestones for faculty that we previously developed and utilized in our own family medicine department.6 To externalize our milestones for use in additional medical specialties, we requested input from educators and specialists throughout our medical center. The example rubric (Figure 1) shows the changes made for the radiology department as an example of how the milestones were customized for each discipline. We then administered the milestones as a self-reported survey to physician educators in five residency programs (Ob/Gyn, oral/maxillofacial surgery (OMFS), radiology, pathology, surgery) at the University of Tennessee Graduate School of Medicine.

Statistical Methods

We performed frequency and descriptive statistics to describe the demographic characteristics of the sample. We assessed the distributions of each professional rating for the statistical assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variance. Since we considered the response sets for the ratings ordinal in terms of measurement, if both statistical assumptions were met, we considered the ratings to be at an interval level of measurement and we utilized parametric one-way analyses of variance to compare the academic appointment groups. If a significant main effect was detected, then we employed post hoc tests using Tukey’s test for pairwise comparisons. Means (M) and standard deviations (SD) were reported for the parametric analyses. If either or both statistical assumptions were violated, then we performed nonparametric Kruskal-Wallis tests to test for significant main effects. We used Mann-Whitney U tests to test for post hoc effects. We reported medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) for the nonparametric analyses. We performed all analyses using SPSS Version 26 (Armonk, NY: IBM Corp.) and statistical significance was assumed at an a value of 0.05.

The Institutional Review Board at the University of Tennessee Graduate School of Medicine examined and approved this study.

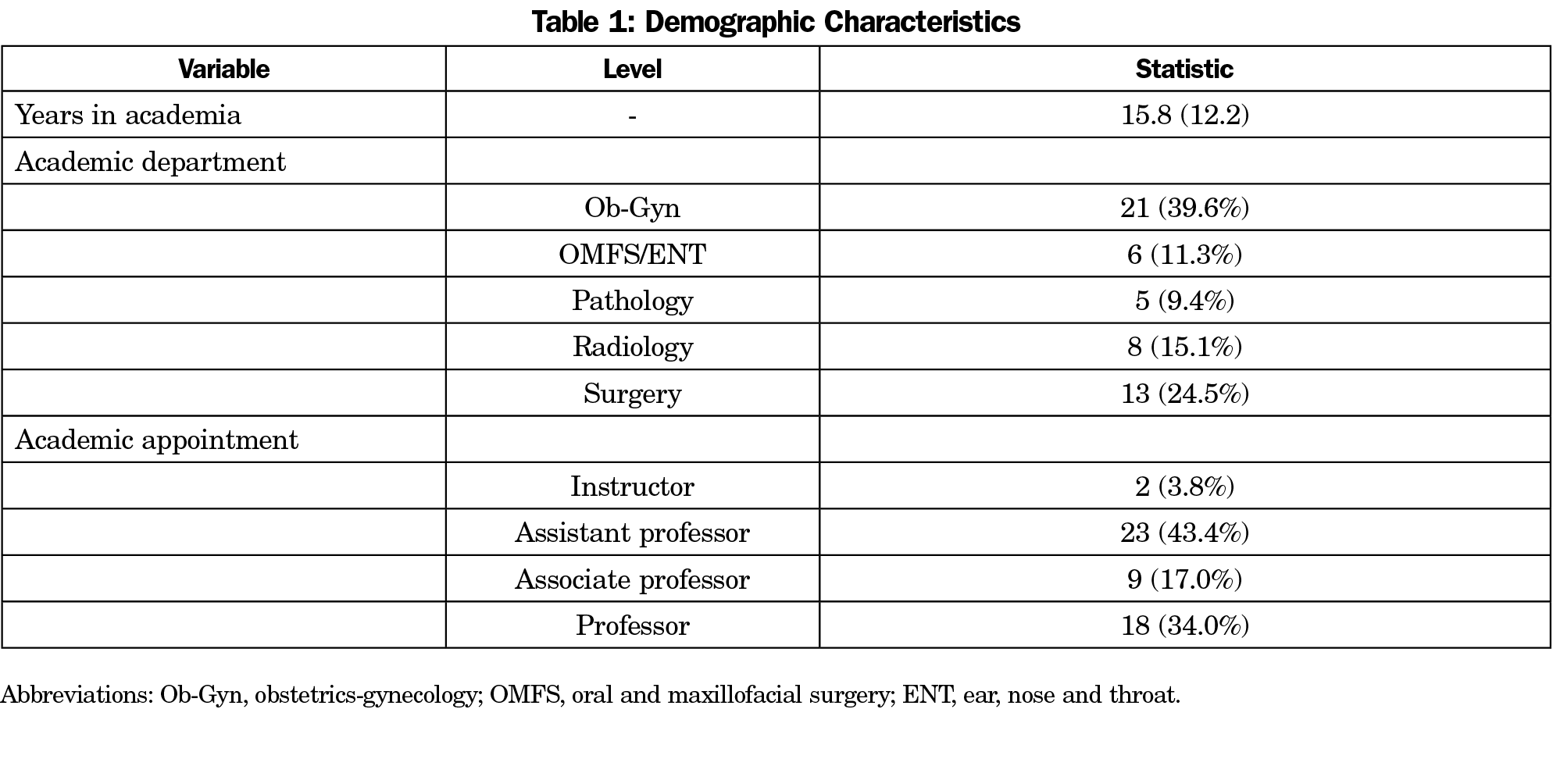

The demographic characteristics of the sample are presented in Table 1. The average number of years in academics was 15.8. The majority of faculty members were in the Ob-Gyn department, and most participants were assistant professors.

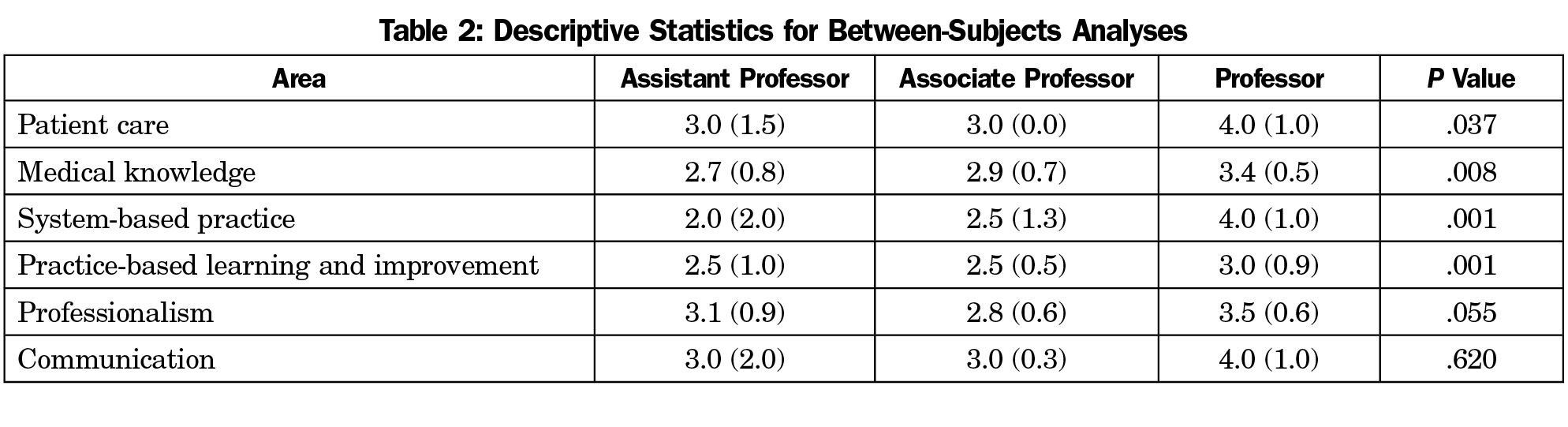

In total, 53 academic physicians responded. The milestones were administered for self-report and the results are analyzed in Table 2. The most significant findings showed correlation between academic rank (assistant vs full professor) and levels of progression in the competencies of medical knowledge and professionalism. Competencies of patient care, systems-based practice, and practice-based learning also showed statistical correlation with progression from assistant to full professor. The levels of associate professor did not show significant correlation to levels of academic achievement when compared to academic rank above or below.

The milestones (Figure 1) identify four levels of progression in a career in academic medicine. The initial level defines those skills based on the six core competency categories for physicians who recently graduated from their residency program. Each core competency establishes activities universal in academics, helping to additionally recognize the differences in patient care based on specific fields of medicine. Those faculty reaching level two may be approaching midcareer progression. Level three defines a mature faculty physician with leadership positions. Those academic physicians who reach positions of leadership on the national or international stage will qualify for level four.

The competency of communication did not appear to correlate well with years of teaching and academic rank. This may be for a variety of reasons including the need for physician educators to have established skill sets in communication, or it may be related to self-perceived competency and difficulty on self-evaluation of competency. This may be an area that is more challenging to assess and quantify without external grading and mentorship.

While it is difficult to score accomplishments across a diverse set of faculty respondents, overall higher academic rank resulted in meeting a higher level of competency. Success in an academic career does not necessarily correlate with a level of competency achievement. The development of doctor/patient relationships, clinical skills, and the internal satisfaction gained from helping develop medical learners and heal patients are fulfilling regardless of academic promotion or career progression. Physicians will gravitate to the levels of their interest and expertise based on their personal characteristics and skills. It is for this reason that these guidelines should not function as a ruler or plumb line to evaluate an individual’s success or serve as an essential process in defining a productive academic career, but rather should function only as a tool for faculty development.

Limitations

We scored this rubric as a self-assessment only, possibly limiting the reliability of the data, since physicians can have difficulty with self-assessment.7 It is difficult to ascertain the utility of this tool based on the current methods of administration. The methods could be strengthened if each faculty surveyed also submits a curriculum vitae (CV) for review by the investigators using a rubric to match achievements on the CV to the milestone model. One-on-one interviews with the faculty could allow examiners to explain the criteria to more accurately complete the milestone rubric. Further customization of the rubric may be necessary to reflect alternative tracks for career advancement, such as a primarily clinical track.

This rubric has been helpful in our institution, providing feedback for directing faculty development and establishing career scholarly activity goals and faculty mentorship. We have recently recruited from within our residency program,8 and it has helped our new faculty to quickly become knowledgeable about the expectations of an academician. These milestones are general enough that other physician specialties may be able to adopt them for their needs. The next goals are to externally validate the milestones, first among departments of family medicine, and then among similar academic medical centers, and ultimately establish uniform guidance for the professional development of career physician educators. Further studies could also focus on the usefulness of this rubric to help retain faculty within academic medicine.

References

- Edgar L, Roberts S, Holmboe E. Milestones 2.0: A Step Forward. J Grad Med Educ. 2018;10(3):367-369. https://doi.org/10.4300/JGME-D-18-00372.1

- Srinivasan M, Li ST, Meyers FJ, et al. “Teaching as a competency”: competencies for medical educators. Acad Med. 2011;86(10):1211-1220. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e31822c5b9a

- Görlitz A, Ebert T, Baver D, Grast M, Hofer M, Lammerding-Köppel M, Fabry G. Core Competencies for Medical Teachers (KLM). A position paper of the GMA Committee on Personal and Organizational Development in Teaching. GMS Zeitschrift für Medizinische Austiktung. 2015; Vol. 32(2); 1/14-7/14

- Bing-You R, Holmboe E, Varaklis K, Linder J. Is it time for entrustable professional activities for residency program directors? Acad Med. 2017;92:739-742. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000001503

- Heath JK, Dine CJ, Burke AE, Andolsek KM. Teaching the teachers with milestones: using the ACGME milestones model for professional development. J Grad Med Educ. 2021;13(2)(suppl):124-126. doi:10.4300/JGME-D-20-00891.1

- Blake GH, Kemmet RK, Jenkins J, Heidel RE, Wilson GA. Milestones as a guide for academic career development. Fam Med. 2019;51(9):760-765. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.109290

- Davis DA, Mazmanian PE, Fordis M, Van Harrison R, Thorpe KE, Perrier L. Accuracy of physician self-assessment compared with observed measures of competence: a systematic review. JAMA. 2006;296(9):1094-1102. doi:10.1001/jama.296.9.1094

- Wilson GA, Jenkins J, Blake GH. Recruiting faculty from within: filling the growing need for family medicine faculty. J Reg Med Campuses. 2020;3(1):1. doi:10.24926/jrmc.v3i1.2149

Lead Author

Rebecca K. Kemmet, MD

Affiliations: Department of Family Medicine, University of Tennessee Graduate School of Medicine, Knoxville, TN

Co-Authors

Gregory H. Blake, MD, MPH - Department of Family Medicine, University of Tennessee Knoxville Graduate School of Medicine, Knoxville, TN

Robert E. Heidel, PhD - Department of Surgery, University of Tennessee Graduate School of Medicine, Knoxville, TN

G. Anthony Wilson, MD - Department of Family Medicine, University of Tennessee Graduate School of Medicine, Knoxville, TN

Corresponding Author

Rebecca K. Kemmet, MD

Correspondence: Department of Family Medicine, University of Tennessee Graduate School of Medicine, 1924 Alcoa Highway, Knoxville, TN 37920. 865-305-5056.

Email: rkemmet@utmck.edu

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.