This century, climate change—a fifth horseman, a new threat of a magnitude unknown to human experience—will ride across our promising landscape of public health. It will ride on a collision course with all the fits and starts of our progress, sometimes fragile, sometimes fundamental.1

COMMENTARIES

Climate Change:

A Crisis for Family Medicine Educators

Monica DeMasi, MD | Bhargavi Chekuri, MD | Heather L. Paladine, MD, MEd | Tina Kenyon, MSW, ACSW

Fam Med. 2022;54(9):683-687.

DOI: 10.22454/FamMed.2022.827476

Climate change poses unparalleled and escalating risks to human health. The increasing frequency of climate-related extreme weather events, heat waves, wildfires, and droughts place unprecedented demands on unprepared health systems and health professionals. Examples like desertification, an ongoing mega-drought, and unrelenting wildfires across the Western United States are all associated with increased outpatient visits, hospitalizations, and death from cardiovascular and respiratory diseases like heart attacks, strokes, and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD).2,3 Globally, loss of life from injuries and disease spread related to flooding, malaria, and diarrhea is expected to increase dramatically as ocean levels rise.3 As the earth warms, we expect infectious diseases such as West Nile virus, dengue, malaria, and Valley fever to reach further north.3 Significant rise in malnutrition related to rising carbon dioxide levels, droughts, and floods are associated with increases in conflict and wars and consequent human displacement3. In addition to physical injury and illness caused by sequelae of climate change, increases in extreme weather events such as hurricanes and tornados lead to displacement, homelessness, and psychological trauma.3

While all humans will be touched by climate change, there is no question that impacts will worsen existing health, gender, and intergenerational inequities.3 Climate change already disproportionately impacts low-income countries that have contributed the least to climate change and people of color living in poverty in high-income countries.3,4 Individuals with unique health needs such as children, women, other sexual and gender minorities, pregnant people, older people, and those with chronic diseases will suffer and die more from heat, unhealthy air quality, malnutrition, and other climate sensitive environmental hazards.3,4 This is relevant as family physicians care for the full life span and are more likely than other physicians to work with underserved populations.

Climate change also damages our capacity to deliver health care.3,4 Extreme climate events impact staff, transportation, utilities, facilities, and supply chains, whose strengths and vulnerabilities have never been more apparent than during the COVID-19 pandemic.3,4 Take for example Hurricane Laura, which caused property destruction, loss of power and access to safe drinking water, and closure of essential services, all leading to mortality and morbidity in Louisiana. Notably, an industrial chemical plant caught fire during the hurricane and was one of many industrial facilities that released millions of toxic emissions contributing to environmental degradation and pollution and worsening existing environmental injustice. A health system already strained by an ongoing pandemic was further impaired when 16 hospitals were forced to evacuate and all temporary COVID-19 testing sites were temporarily shut down. A subsequent heat wave in the state was associated with additional mortality and morbidity due to loss of power, damages to essential infrastructure, and increased heat exposure for outdoor workers and other high-risk groups like older individuals.5

The World Health Organization identified climate change as the greatest threat to human health in the 21st century in 2009. Since then, the American Medical Association,6 American Academy of Family Physicians,7 American College of Physicians,8 American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists9 and American Academy of Pediatrics10 have all advocated for protecting human health by mitigating climate change in legislation, increasing medical education around this topic, and increasing support for health professionals and health systems to adapt and become more resilient to climate change. When surveyed, the vast majority of family physicians in the United States feel that climate change is relevant to direct patient care and more than half report feeling their own patients are already significantly harmed by climate change.11,12 The most trusted source of information on environmental health are family physicians.12 As health providers focused on preventive medicine and advancing health equity, family physicians must better understand effects of climate change on our communities so we can prevent and respond to likely consequences.13,14 As clinicians who care for children, family physicians have an even greater moral responsibility to address climate change because more than 88% of the harms of climate change are estimated to be felt by children under the age of 5 years.10 Most importantly, family physicians can lead at the intersection of climate change and health equity. Family doctors are experts in leveraging long-term relationships with our communities, while utilizing storytelling and interprofessional care to effectively communicate and advocate about health risks as well as lead individual and social behavior change and systems transformations.15

Family Physicians Must Mitigate the Impact of Climate Change on our Patients and Communities on Many Levels

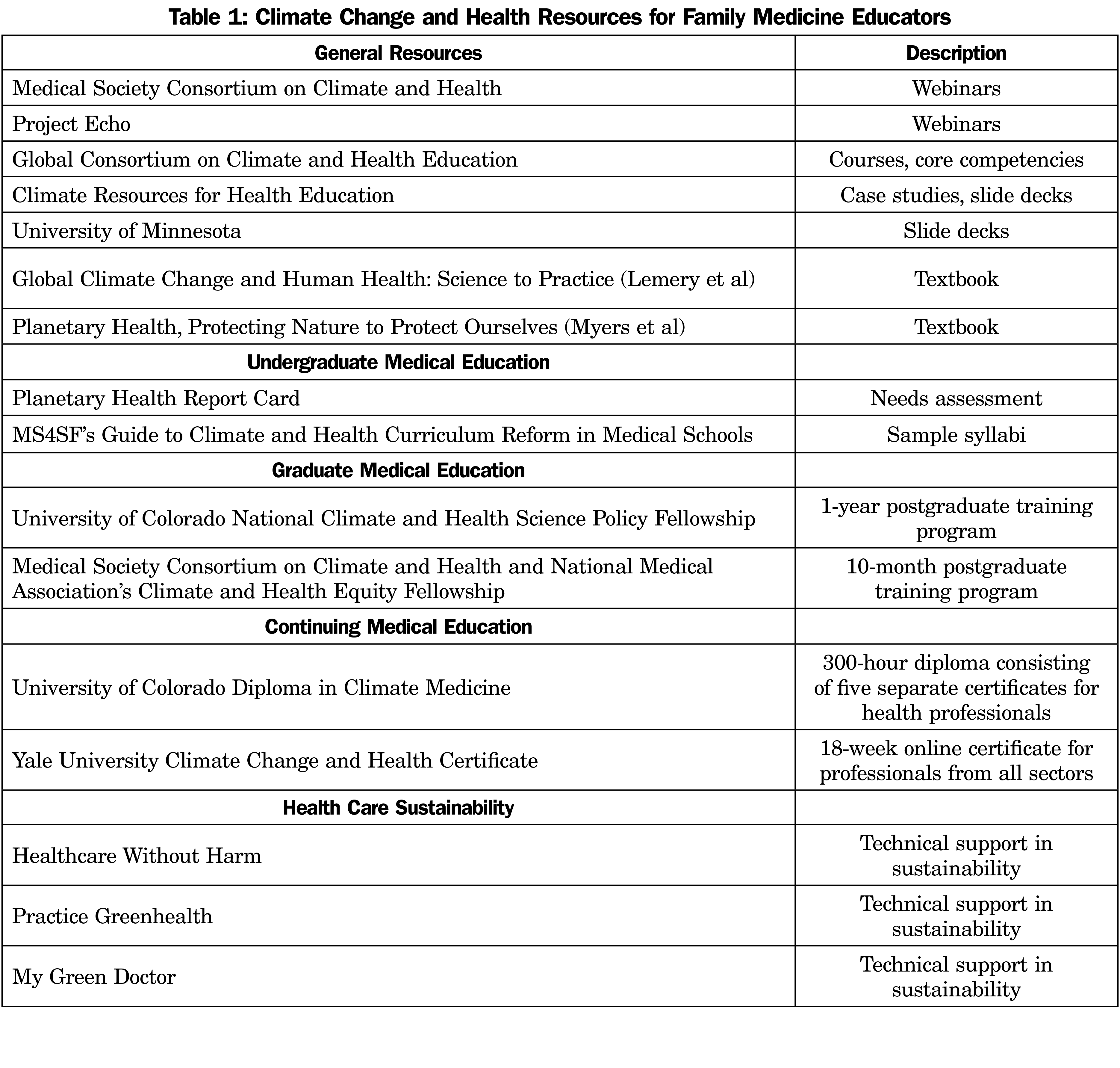

Education. Family medicine educators have a role to play in preventing and mitigating the health impacts of climate change, both in our actions now and in preparing future family physicians to practice in a changing world.13 However, medical schools16 and residencies17,18 in general are not teaching about climate change. As of 2019, only 16% of medical schools have climate change in their curricula. 16 As educators, we can lead and advocate for climate change education at our institutions. The Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) and Association of American Medical Colleges (AAMC) actively promote emergency preparedness and health equity, both inextricably interwoven with climate change. The AAMC states on its website, “All physicians, whether in training or in practice for many years, have to be able to assess for, manage, and effectively treat the health effects of climate change.”19 As family medicine educators, we are poised to provide climate change continuing education to interprofessional care teams within our health systems. We should integrate climate change subject matter into our lectures and curricula for medical students, residents, and fellows.20 The Planetary Health Report Card serves as an excellent needs assessment.21 It provides measurable metrics with which medical schools can track their progress on integrating climate change and health education. The Global Consortium on Climate Change and Health Education,22 Project Echo,23 Climate Psychiatry Alliance24 and the Medical Society Consortium on Climate and Health25 all provide readily available learning competencies, educational webinars, and sample course syllabi which can be adapted and used by individual programs. Family medicine educators can role model climate change awareness in patient care and teach individual or small groups of students about climate change. Postgraduate fellowships in climate change and health provide opportunities for learners wanting to develop further expertise.26,27 Faculty and leadership development in climate change and health is crucial to modernizing the academic family medicine landscape. Resources such as University of Colorado’s Diploma and Certificates in Climate Medicine28 and Yale’s Climate Change and Health Certificate29 are available. Lastly, family medicine educators should participate in and advocate for primary care driven scholarship and research on how to decrease climate change impacts on public health.

Patient Care. We should address climate change in our interactions with individual patients at every opportunity.14 We should learn about local environmental health risks to our patients and subsequently provide anticipatory guidance about how to manage them. For example, if you are caring for an elderly patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease in an area that frequently experiences wildfires, you might inform your patient about the benefits of staying inside on smoky days. Furthermore, you might leverage social work programs to help them get air conditioners with filters and discuss when it would be appropriate for them to contact the office. During our annual visits and well-child checks, we can work harder and more effectively to promote plant-forward foods to our patients as this serves as one of the most powerful forms of climate action that improves individual and planetary health simultaneously.

Practice Transformation. We should change our clinics and health systems to be proactive in mitigating and adapting to climate change. The American health sector alone contributes to 7%-10% of total US greenhouse gas emissions.30 One study found that pollution from the health sector is estimated to cause health damages on the same order of magnitude as preventable medical errors.30 Within this context, decarbonizing the health sector has been framed as a patient safety issue30 and in line with family medicine’s core principles of do no harm and preventive medicine. Strong models and roadmaps for greening our clinics and hospital systems exist, such as Health Care Without Harm’s Global Road Map for Health Care Decarbonization31 and Practice Greenhealth’s Climate Impact Checkup tool.32 These can be leveraged to lead innovative quality improvement projects focused on reducing the harms created by our workplaces. The COVID-19 pandemic also provides valuable lessons about sustainability. While waste from personal protective equipment (PPE), test kits, and vaccines have overwhelmed health systems, the pandemic has demonstrated the financial and health benefits of pursuing sustainable solutions like eco-friendly packaging and shipping, reusable PPE, and utilizing nonburn waste treatments. We should lead research and innovation in, as well as advocate for the use of these technologies and policies. Similarly, we should advocate for strengthening and modernizing telehealth services, or having some staff work from home as these policies decrease our carbon footprint and make health systems more resilient during climate-driven disasters. Lastly, we can proactively prepare for the effects of climate change. For example, in a region with increasing heat waves, we can deploy early warning systems and distribute lists of cooling centers, or have community health workers check in on particularly vulnerable patients. By diving into climate action in our own house, the health care sector can lead other industries in building a healthier future.

Advocacy. Advocacy skills are required in the ACGME Family Medicine Milestones for resident education, and are core to the family physician’s role.33 We must be involved in local and national policy discussions that address the health of our patients and communities and protect the most vulnerable. We can encourage our organizations to divest of fossil fuel investments. We can lobby with colleagues and medical societies to help lawmakers draft new legislation. We can join or collaborate with physician organizations working on this problem such as the Medical Society Consortium on Climate and Health, Healthcare Without Harm, EcoAmerica, or Physicians for Social Responsibility.20 In addition, we should advocate for our organizations such as the Society of Teachers of Family Medicine to officially recognize climate change as an emergent priority. We should urge our institutions such as the AAMC and ACGME to require climate change education as core topics in the formation of new physicians in all specialties. In collaboration with colleagues in other branches of science, we can highlight compelling evidence of the need for policy change. We should leverage our voices as stewards of public health to advocate for change in local and national governmental policies.

There is now ample evidence that human behavior is changing our climate in ways that are having catastrophic and worsening health impacts on humanity. As family physicians and educators, we are uniquely empowered to mitigate and manage these issues. Our learners are the future of family medicine, and indeed, all medical specialties. We can and must prepare them to protect their patients from climate-sensitive environmental health risks and to act as leading change agents in climate action. As stewards of current and future community health, we and our future family doctors must act at local, institutional, and global levels to both prevent the worst impacts of climate change and to buffer our patients from what may become unavoidable.14,20 For more information on what you can do as a clinician and educator, consult resources such as the references cited here and websites such as the Center for Climate Change and Health (https://climatehealthconnect.org/resources/physicians-guide-climate-change-health-equity/). Working together, we can make a positive difference to combat the effects of climate change on the lives of patients, families, the health care team, communities, our nation, and our world.

References

- Chan M. World Health Organization. Climate change and health: preparing for unprecedented challenges. Geneva, Switz: World Health Organization; 2007. Accessed March 26, 2013. www.who.int/dg/speeches/2007/20071211_maryland/en/index.html

- Wegesser TC, Pinkerton KE, Last JA. California wildfires of 2008: coarse and fine particulate matter toxicity. Environ Health Perspect. 2009;117(6):893-897. doi:10.1289/ehp.0800166

- Romanello M, McGushin A, Di Napoli C, et al. The 2021 report of the Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change: code red for a healthy future. Lancet. 2021;398(10311):1619-1662. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01787-6

- Smith K, et al. Human health: impacts, adaptation, and co-benefits. In: Climate Change 2014: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Part A: Global and Sectoral Aspects. Contribution of Working Group II to the fifth assessment report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.Cambridge University Press; 2014:709-754.

- Beyeler, Naomi, et al. Case Study – Compounding Crises of Our Time During Hurricane Laura Climate Change, COVID-19, and Environmental Injustice. 2020 Lancet Countdown on Health and Climate Change, Policy Brief for the United States of America;December2020. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.lancetcountdownus.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/cs-compounding.pdf

- Robeznieks A. Doctors demand presidential action on climate change. American Medical Association; January 10, 2020. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/public-health/doctors-demand-presidential-action-climate-change

- American Academy of Family Physicians. Environmental Health and Climate Change. AAFP; December 12, 2019. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.aafp.org/about/policies/all/environmental-health.html

- Crowley A. Climate Change and Health: A Position Paper of the American College of Physicians. May 3, 2016. doi:10.7326/M15-2766

- Council on Environmental Health; Paulson JA, Ahdoot S, Baum CR, et al. Global Climate Change and Children’s Health. PediatricsNovember 2015; 136 (5): 992–997. doi: 10.1542/peds.2015-3232

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Addressing Climate Change, Position Statement. November 2021. Accessed May 2022. https://www.acog.org/clinical-information/policy-and-position-statements/position-statements/2021/addressing-climate-change?utm_source=redirect&utm_medium=web&utm_campaign=int#references

- Sarfaty M, Mitchell M, Bloodhart B, Maibach EW. A survey of African American physicians on the health effects of climate change. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2014;11(12):12473-12485. doi:10.3390/ijerph111212473

- Boland TM, Temte JL. Family medicine patient and physician attitudes toward climate change and health in Wisconsin. Wilderness Environ Med. 2019;30(4):386-393. doi:10.1016/j.wem.2019.08.005

- Abelsohn A, Rachlis V, Vakil C. Climate change: should family physicians and family medicine organizations pay attention? Can Fam Physician. 2013;59(5):462-466.

- Lodge A. Anthropogenic climate change is here: family physicians must respond to the crisis. Can Fam Physician. 2015;61(7):582-583, e293-e294.

- Stange KC, Jaén CR, Flocke SA, Miller WL, Crabtree BF, Zyzanski SJ. The value of a family physician. J Fam Pract. 1998;46(5):363-368.

- Earls M. Despite climate change health threats, few medical schools teach it. Sci Am. 2019;(December):27. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://www.scientificamerican.com/article/despite-climate-change-health-threats-few-medical-schools-teach-it/

- AAFP News Staff. What do FM Residents Know About. Environ Health. 2019;17. July 17, 2019. Accessed September 12, 2022. https://www.aafp.org/news/education-professional-development/20190717residentenvirohealth.html

- Philipsborn RP, Sheffield P, White A, Osta A, Anderson MS, Bernstein A. Climate change and the practice of medicine: essentials for resident education. Acad Med. 2021;96(3):355-367. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003719

- Balch B. AAMCNews & Insights. Association of American Medical Colleges. April 22, 2022. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://www.aamc.org/news-insights

- Wellbery C, Sheffield P, Kavya T, et al. It’s time for medical schools to introduce climate change into their curricula. Acad Med. 2018.93(12): 1774. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002368

- The Planetary Health Report Card. May 2022. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://phreportcard.org/

- Global Consortium on Climate Change and Health Education. May 2022. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://www.publichealth.columbia.edu/research/global-consortium-climate-and-health-education

- Climate Change and Human Health ECHO Program. University of New Mexico. May 2022. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://hsc.unm.edu/echo/partner-portal/programs/global/climate-change/

- Learn About Climate Psychiatry. Climate Psychiatry Alliance. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://www.climatepsychiatry.org/learn-1

- Medical Society Consortium on Climate and Health. May 2022. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://medsocietiesforclimatehealth.org/

- Climate & Health Science Policy Fellowship. University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. May 2022. Accessed September 2022.https://medschool.cuanschutz.edu/climateandhealth/education/fellowship

- Climate and Health Equity Fellowship. The Medical Society Consortium. May 2022. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://medsocietiesforclimatehealth.org/climate-health-equity-fellowship-chef/

- Introducing the Diploma in Climate Medicine. University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus. May 2022. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://medschool.cuanschutz.edu/climateandhealth/diploma-in-climate-medicine

- Climate Change and Health Certificate program. Yale School of Public Health. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://ysph.yale.edu/cchcert/program/cme/

- Eckelman MJ, Huang K, Lagasse R, Senay E, Dubrow R, Sherman JD. Health Care Pollution And Public Health Damage In The United States: An Update. Health Aff (Millwood). 2020 Dec;39(12):2071-2079

- Global Road Map for Health Care Decarbonization. Health Care Without Harm. 2021. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://healthcareclimateaction.org/roadmap

- Climate Impact Checkup. Practice Greenhealth. May 2022. September 13, 2022. https://practicegreenhealth.org/topics/climate-and-health/climate-impact-checkup

- ACGME Program Requirements for Graduate Medical Education in Family Medicine. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education. July 2021. Accessed September 13, 2022. https://www.acgme.org/globalassets/pfassets/programrequirements/120_familymedicine_2021.pdf

- Parker CL, Wellbery CE, Mueller M. The changing climate: managing health impacts. Am Fam Physician. 2019;100(10):618-626.

Lead Author

Monica DeMasi, MD

Affiliations: Providence Health & Services Family Medicine Residency Program, Portland, OR

Co-Authors

Bhargavi Chekuri, MD - University of Colorado, Anschutz Medical Campus, Aurora, CO

Heather L. Paladine, MD, MEd - Columbia University Medical Center, New York, NY

Tina Kenyon, MSW, ACSW - Dartmouth Family Medicine Residency Program, Concord, NH

Corresponding Author

Monica DeMasi, MD

Correspondence: Providence Health and Services Oregon and Southwest Washington - Family Medicine, 4104 SE 82nd Ave, Portland, OR 97213-2933

Email: monica.demasi@providence.org

Fetching other articles...

Loading the comment form...

Submitting your comment...

There are no comments for this article.