Background and Objectives: While there is increased attention to underrepresented in medicine (URiM) faculty and students, little is known about what they value in faculty development experiences.

Methods: We performed a URiM-focused, 3-day family medicine faculty development program and then collected program evaluation forms. The program evaluations had open-ended questions and a reflection on the activity. We used inductive open coding using NVivo software. We analyzed open-ended responses and reflections, and identified themes.

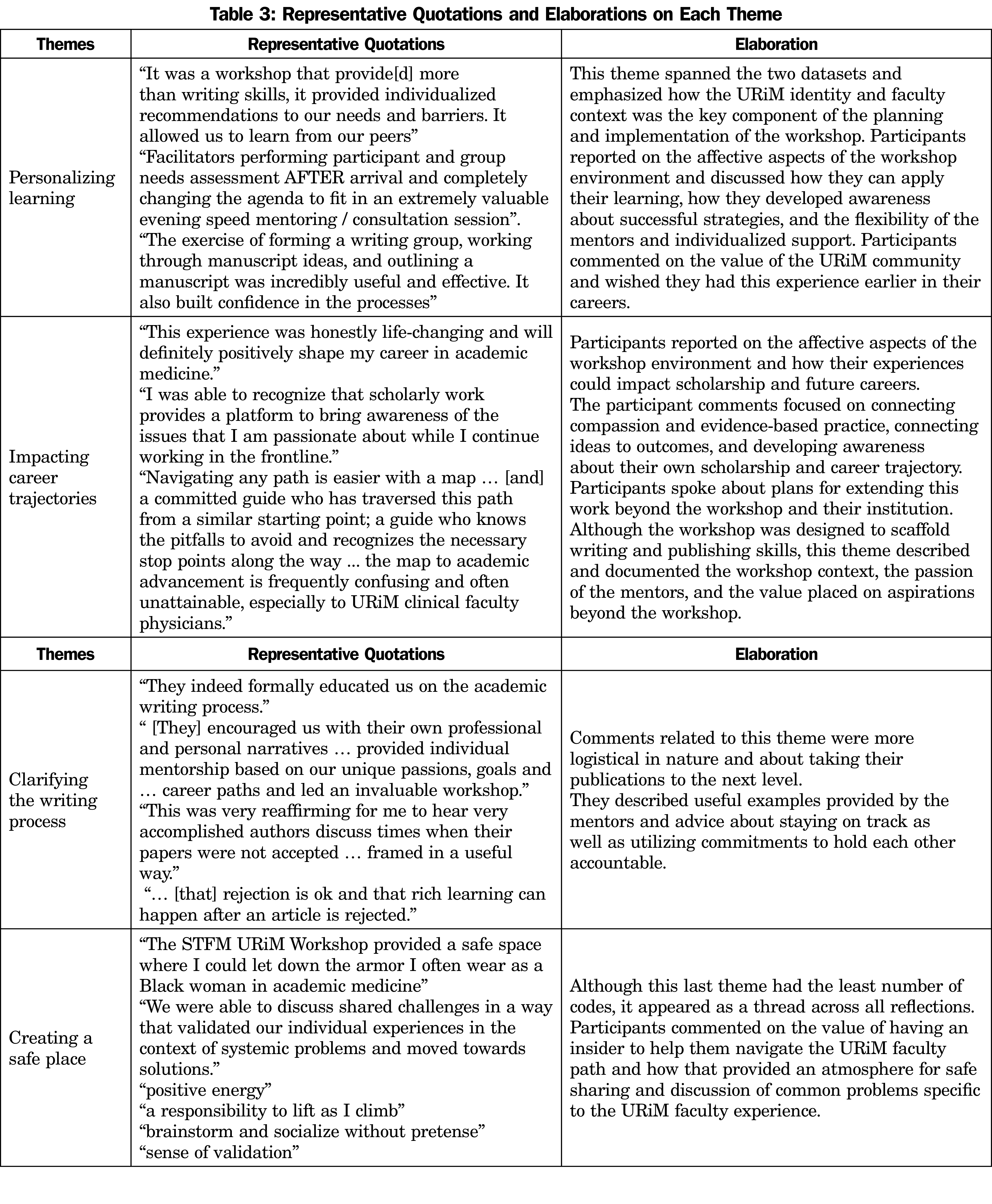

Results: Seven participants provided reflections on the workshop and responses to the evaluation forms. Analysis revealed four major themes in the learners’ responses and reflections: (1) personalizing learning, (2) impacting career trajectories, (3) clarifying the writing process, and (4) creating a safe place, with frequencies of 28.2%, 26.7%, 23.6%, and 20.9%, respectively.

Conclusions: Although this faculty development experience was designed to teach writing skills to URiM junior faculty, their collective responses indicate that they found value beyond the skills taught and appreciated the approach taken in this activity.

The diversity of the physician workforce lags significantly behind the population.1 In academia, underrepresented in medicine (URiM) physicians account for only 10.6% of all US medical school faculty.2 For the purposes of this study, those underrepresented in medicine include people from Black or African American, Latinx (Hispanic or Latino), American Indian/Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian, or other Pacific Islander backgrounds, although other groups may be underrepresented in certain areas.3

URiM faculty experience pressure to take on professional and institutional responsibilities that may not contribute to their academic advancement.4,5 This phenomenon is part of a series of disparities termed the “minority tax.”6 The minority tax includes diversity efforts disparities, isolation, lack of mentorship, faculty development, and racism,6 causing the URiM faculty who persist in the career to be more likely to leave in 5 years than their non-URiM colleagues.7,8

URiM faculty are at the assistant professor rank more often and tenured less often than non-underrepresented colleagues,2 highlighting the need for URiM focused faculty development. We report the participants’ impressions of a URiM focused family medicine early career faculty development workshop led by senior URiM family medicine faculty, entitled the Leadership through Scholarship Fellowship.10 This approach was structured as a racial/ethnic concordant experience between faculty and fellows, as the faculty and participants were Latino and Black. We call this approach “for us, by us,” and describe it as a new approach for URiM faculty development.11 Similar to the literature on improved patient outcomes when Black patients have Black doctors,12-14 this approach was used for faculty development, with the outcomes of peer reviewed publications and readiness for promotion.11 The workshop addressed the unique needs of URiM faculty and allowed for URiM faculty to share the obstacles they face,15 recognizing that they will likely hold multiple positions in each of the domains of family medicine.16 This project adds to the literature in that learner perspectives of URiM faculty development are rarely presented but are an important guide to improving faculty development for this group.17,18

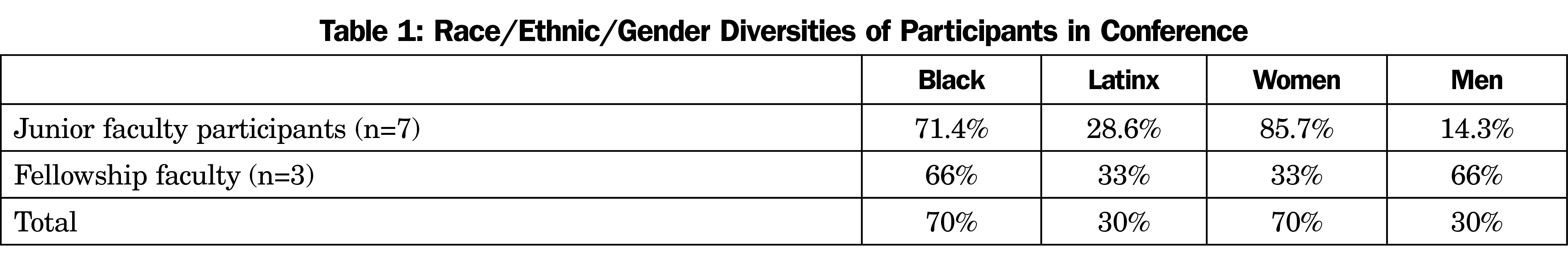

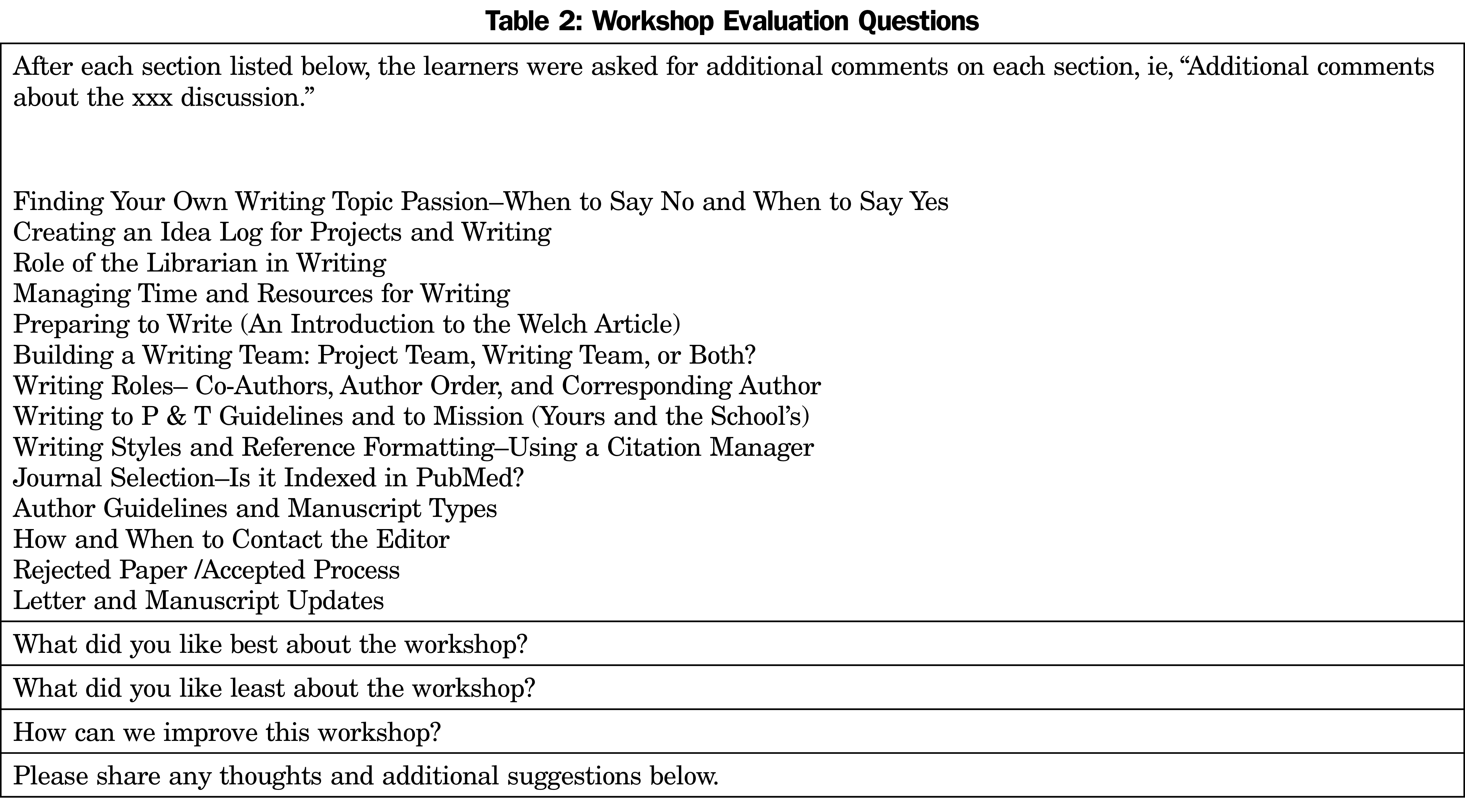

This qualitative study was deemed exempt by the University of Utah Institutional Review Board. We asked each participant to answer 18 open-ended questions as part of the program evaluation at the conclusion of the workshop. In addition to the survey, the participants were asked to submit a reflection on the workshop, using the prompt, “Please reflect upon the faculty development workshop and share your thoughts.” This request was sent out by email and participants responded. We analyzed the responses to the questions (survey data set) and the reflections (reflections data set) through rigorous qualitative methods utilized using Nvivo software (QSR International, Doncaster, Australia). We first was first open-coded the text inductively, allowing themes to emerge from the data using techniques described by Corbin, Strauss, and Saldaña.19,20 Then, we performed axial coding or category/theme organization. Finally, we conducted a process of selective coding to look at the relationships of the coding and categories/themes, as well as the relationship of themes across the two distinct bodies of text. The final stage of this analysis included an abductive reasoning process as outlined by Charmaz.21 Demographic information on the participants is presented in Table 1. Questions from this survey are presented in Table 2.

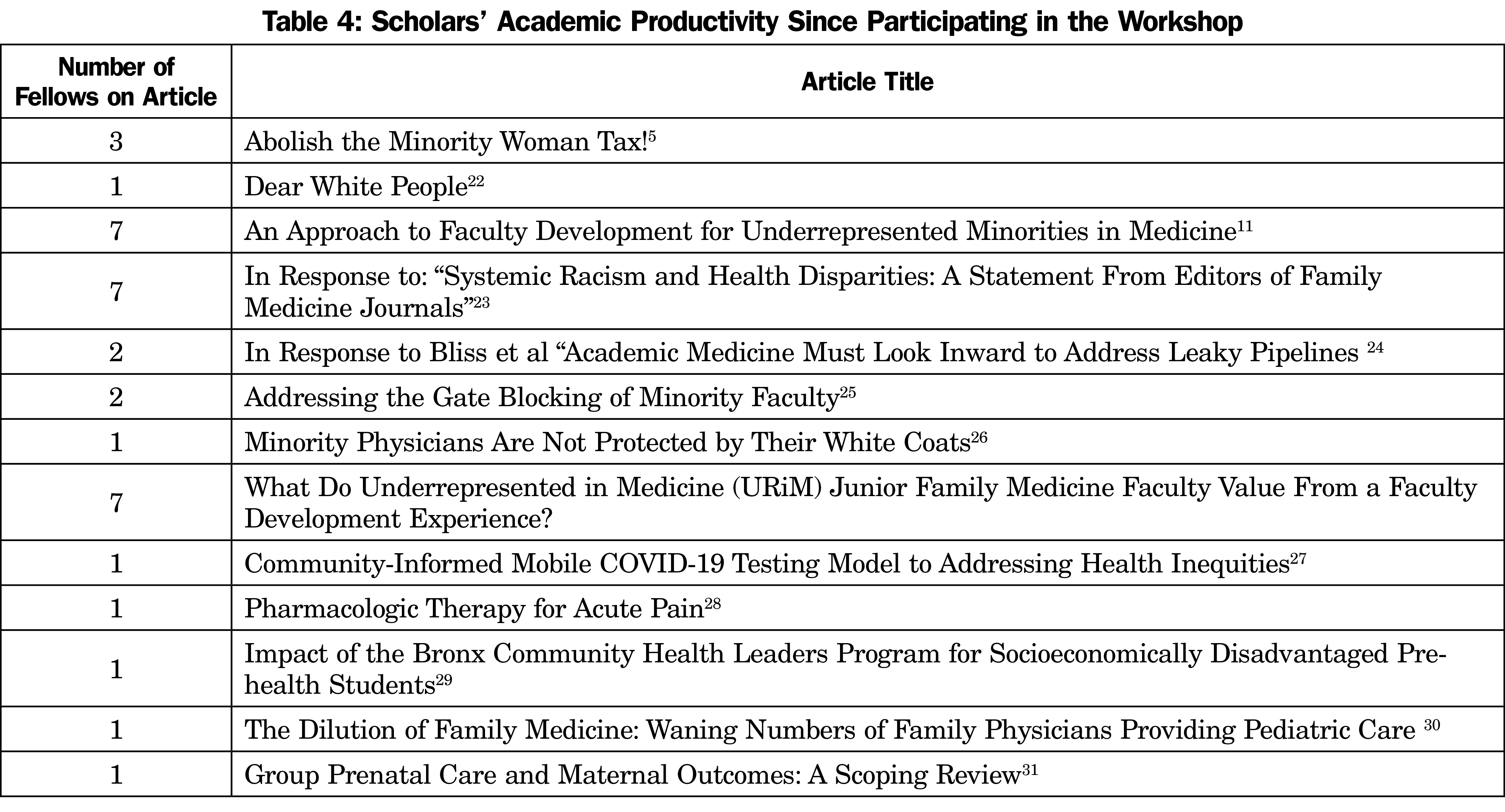

To ensure that the study went beyond Kirkpatrick level 1 (learner reactions) analysis, we followed the participants for 2 years after the workshop and collected their publications and their applications for academic promotion.

We identified 191 unique codes from the seven participants’ responses to open-ended questions and reflections. The survey data set contained 63.6% of the total coding, while the reflections contained 34.4%. We categorized codes into four themes: (1) personalizing learning, (2) impacting career trajectories, (3) clarifying the writing process, and (4) creating a safe place. The coding frequency percentages were evenly proportioned across the four themes: 28.2%, 26.7%, 23.6%, and 20.9%, respectively. The themes, with representative quotations and elaborations, are illustrated in Table 3. It is notable that participants spoke frequently about the adaptation of a general curriculum to meet specific individual needs, as well as the transformative impact that they felt the activity had on their careers. Learners also expressed their gratitude for feeling free to bring their authentic selves to the activity without fear of judgement.

Table 4 presents the participants’ productivity in the production of scholarship from the start of the workshop to 24 months later. In addition, two participants are submitting materials to their promotion and tenure committees for consideration for promotion to associate professor this year.

These findings suggest that URiM early career family medicine faculty value (1) personalizing learning; (2) impacting career trajectories; (3) clarifying the writing process; and (4) creating a safe place. In addition, the increased publications from this group after the fellowship also indicate that the participants could apply the skills learned in the workshop to complete and publish manuscripts and prepare for promotion. The results also suggest that an approach of “for us by us” is valued, and this is a principal innovation of this study.

Several limitations challenge the results of this study. First, there was a small cohort of scholars in the first iteration of the fellowship. Second, the more senior-career URiM faculty were not designated faculty development officers at their respective institutions. Third, it is also a possibility that there was a Hawthorne effect, as the participants knew they were being observed, and that could have influenced their responses and could have influenced the questions that they were asked.32 There has been little added to the literature since the authors’ (J.E.R., K.M.C.) work in 2014 that outlines how faculty development for URiM faculty should be structured.37 Few faculty development experiences for URiM faculty provided by URiM faculty exist that address the minority tax and its impact on the retention and recruitment of this group.

One participant’s reflection summarizes the overall sentiments of the participants:

“This 3-day experience was encouraging, energizing, immensely therapeutic and will undoubtedly prove to be a pivotal point in the trajectory of my career. I now have much more than a map, but a clear, strategic design for moving along the path of academic advancement and the blessing of an exceptional cohort of guides and fellow travelers.”

Even though the pilot of this offering was directed only at family medicine faculty, this type of faculty development opportunity has the potential to advance the careers of URiM faculty, regardless of specialty. Personalized mentorship is beneficial for URiM early-career faculty and can and should be extrapolated and refocused to all areas and specialties.

Acknowledgments

Funding Statement: This work was funded by an STFM Grant to the Minority and Multicultural Health Collaborative, now named the Leadership Through Scholarship Fellowship.

References

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Rayburn WF. Full-time faculty in clinical and basic science departments by sex and underrepresented in medicine status: a 40-year review. Acad Med. 04 01 2021;96(4):568-575. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000003925

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Syed ZA, Shakil A, Schneider FD. Recent trends in faculty promotion in U.S. medical schools: implications for recruitment, retention, and diversity and inclusion. Acad Med. 10 01 2021;96(10):1441-1448. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000004188

- Underrepresented in Medicine Definition. Association of American Medical Colleges. Accessed January 31, 2014. https://www.aamc.org/what-we-do/equity-diversity-inclusion/underrepresented-in-medicine

- Campbell KM, Rodríguez JE. Addressing the minority tax: perspectives from two diversity leaders on building minority faculty success in academic medicine. Acad Med. 2019;94(12):1854-1857. doi:10.1097/ACM.0000000000002839

- Rodriguez JE, Wusu MH, Anim T, Allen KC, Washington JC. Abolish the minority woman tax! J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2020. doi:10.1089/jwh.2020.8884

- Rodríguez JE, Campbell KM, Pololi LH. Addressing disparities in academic medicine: what of the minority tax? BMC Med Educ. 2015;15(1):6. doi:10.1186/s12909-015-0290-9

- Cropsey KL, Masho SW, Shiang R, Sikka V, Kornstein SG, Hampton CL; Committee on the Status of Women and Minorities, Virginia Commonwealth University School of Medicine, Medical College of Virginia Campus. Why do faculty leave? Reasons for attrition of women and minority faculty from a medical school: four-year results. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2008;17(7):1111-1118. doi:10.1089/jwh.2007.0582

- Carr PL, Palepu A, Szalacha L, Caswell C, Inui T. ‘Flying below the radar’: a qualitative study of minority experience and management of discrimination in academic medicine. Med Educ. 2007;41(6):601-609. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2923.2007.02771.x

- Bonifacino E, Ufomata EO, Farkas AH, Turner R, Corbelli JA. Mentorship of underrepresented physicians and trainees in academic medicine: a systematic review. J Gen Intern Med. 04 2021;36(4):1023-1034. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06478-7

- Leadership Through Scholarship Fellowship. Society of Teachers of Family Medicine. Accessed January 24, 2022. https://www.stfm.org/facultydevelopment/fellowships/leadershipthroughscholarship/overview/

- Robles J, Anim T, Wusu MH, et al. An approach to faculty development for underrepresented minorities in medicine. South Med J. 2021;114(9):579-582. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001290

- Greenwood BN, Hardeman RR, Huang L, Sojourner A. Physician-patient racial concordance and disparities in birthing mortality for newborns. Proc Natl Acad Sci. 09 2020;117(35):21194-21200. doi:10.1073/pnas.1913405117

- Ma A, Sanchez A, Ma M. The impact of patient-provider race/ethnicity concordance on provider visits: updated evidence from the medical expenditure panel survey. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 10 2019;6(5):1011-1020. doi:10.1007/s40615-019-00602-y

- Meghani SH, Brooks JM, Gipson-Jones T, Waite R, Whitfield-Harris L, Deatrick JA. Patient-provider race-concordance: does it matter in improving minority patients’ health outcomes? Ethn Health. 2009;14(1):107-130. doi:10.1080/13557850802227031

- Robles J, Anim T, Wusu MH, et al. An approach to faculty development for underrepresented minorities in medicine. South Med J. 2021;114(9):579-582. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000001290

- Coe C, Piggott C, Davis A, et al. Leadership pathways in academic family medicine: focus on underrepresented minorities and women. Fam Med. 2020;52(2):104-111. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.545847

- Weber RA, Cable CT, Wehbe-Janek H. Learner perspectives of a surgical educators faculty development program regarding value and effectiveness: a qualitative study. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2016;137(3):1057-1061. doi:10.1097/01.prs.0000475825.09531.68

- Guevara JP, Adanga E, Avakame E, Carthon MB. Minority faculty development programs and underrepresented minority faculty representation at US medical schools. JAMA. 2013;310(21):2297-2304. doi:10.1001/jama.2013.282116

- Corbin JM, Strauss AL. Basics of qualitative research : techniques and procedures for developing grounded theory. 3rd ed. Sage Publications, Inc.; 2008:xv, 379 pages. doi:10.4135/9781452230153

- Saldana J. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 3rd edition. Sage; 2016:xiv.

- Charmaz K. Grounded theory as an emergent method. In: Hess-Bieber SN, Levey P, eds. Handbook of Emergent Methods.The Guilford Press; 2008:155-172.

- Foster KE, Johnson CN, Carvajal DN, et al. Dear white people. Ann Fam Med. 2021 Jan-Feb 2021;19(1):66-69. doi:10.1370/afm.2634

- Parra Y, Anim T, Foster KE, et al. In response to: "Systemic Racism and Health Disparities: A Statement From Editors of Family Medicine Journals." Fam Med. 2021;53(6):470-471. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.423229

- Amaechi O, Foster KE, Robles J, Campbell K. In response to bliss et al: academic medicine must look inward to address leaky pipelines. Fam Med. 2021;53(8):729. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2021.949502

- Amaechi O, Foster KE, Tumin D, Campbell KM. Addressing the gate blocking of minority faculty. J Natl Med Assoc. 2021;113(5):517-521. doi:10.1016/j.jnma.2021.04.002

- Amaechi O, Rodríguez JE. Minority physicians are not protected by their white coats. Fam Med. 2020;52(8):603. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2020.737963

- Jiménez J, Parra YJ, Murphy K, et al. Community-informed mobile COVID-19 testing model to addressing health inequities. J Public Health Manag Pract. 2022 Jan-Feb 01 2022;28(Suppl 1):S101-S110. doi:10.1097/PHH.0000000000001445

- Amaechi O, Huffman MM, Featherstone K. Pharmacologic therapy for acute pain. Am Fam Physician. 2021;104(1):63-72.

- Robles J, Qadeer R, Reyes Adames T, Naqvi Z. Impact of the Bronx Community Health Leaders Program for Socioeconomically Disadvantaged Prehealth Students. Health Equity. 2021;5(1):791-800. doi:10.1089/heq.2021.0065

- Anim T.E. The dilution of family medicine: waning numbers of family physicians proiding pediatric Care. J Am Board Fam Med. 2020 Nov-Dec 2020;33(6):828-829. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2020.06.200544

- Tucker CM, Felder TM, Dail RB, Lyndon A, Allen KC. Group prenatal care and maternal outcomes: a scoping review. MCN Am J Matern Child Nurs. 2021;46(6):314-322. doi:10.1097/NMC.0000000000000766

- Sedgwick P, Greenwood N. Understanding the Hawthorne effect. BMJ. 2015;351:h4672. doi:10.1136/bmj.h4672

- Richert A, Campbell K, Rodríguez J, Borowsky IW, Parikh R, Colwell A. ACU workforce colvumn: expanding and supporting the health care workforce. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2013;24(4):1423-1431. doi:10.1353/hpu.2013.0162

- Kreuter MW, Holmes K, Alcaraz K, et al. Comparing narrative and informational videos to increase mammography in low-income African American women. Patient Educ Couns. 2010;81(suppl):S6-S14. doi:10.1016/j.pec.2010.09.008

- Campbell KM, Brownstein NC, Livingston H, Rodríguez JE. Improving underrepresented minority in medicine representation in medical school. South Med J. 04 2018;111(4):203-208. doi:10.14423/SMJ.0000000000000792

- Campbell KM, Hudson BD, Tumin D. Releasing the net to promote minority faculty success in academic medicine. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 04 2020;7(2):202-206. doi:10.1007/s40615-020-00703-z

- Rodriguez JE, Campbell KM, Fogarty JP, Williams RL. Underrepresented minority faculty in academic medicine: a systematic review of URM faculty development. Fam Med. 2014;46(2):100-104.

- Najibi S, Carney PA, Thayer EK, Deiorio NM. Differences in coaching needs among underrepresented minority medical students. Fam Med. 2019;51(6):516-522. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.100305

There are no comments for this article.