Background and Objectives: Patients are best served by a health care workforce that reflects the diversity of their community. Increasing diversity of family medicine requires a long-term effort to recruit more medical students from underrepresented in medicine (URiM, defined as people of Black/African American, Hispanic/Latino, Native American or Pacific Islander heritage) backgrounds into family medicine residencies. This paper examines factors that influence URiM medical students to choose family medicine residencies.

Methods: Data were collected via a Council of Academic Family Medicine Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine clerkship directors. Correlations examined associations between the percent URiM faculty, percent URiM preceptors, percent clerkship cases addressing health equity, and the percent of URiM students choosing family medicine residencies. t tests determined associations between clerkship director race, preclinical electives on health equity, department faculty champion for diversity, and department diversity activities; and the percentage of URiM students choosing family medicine residencies.

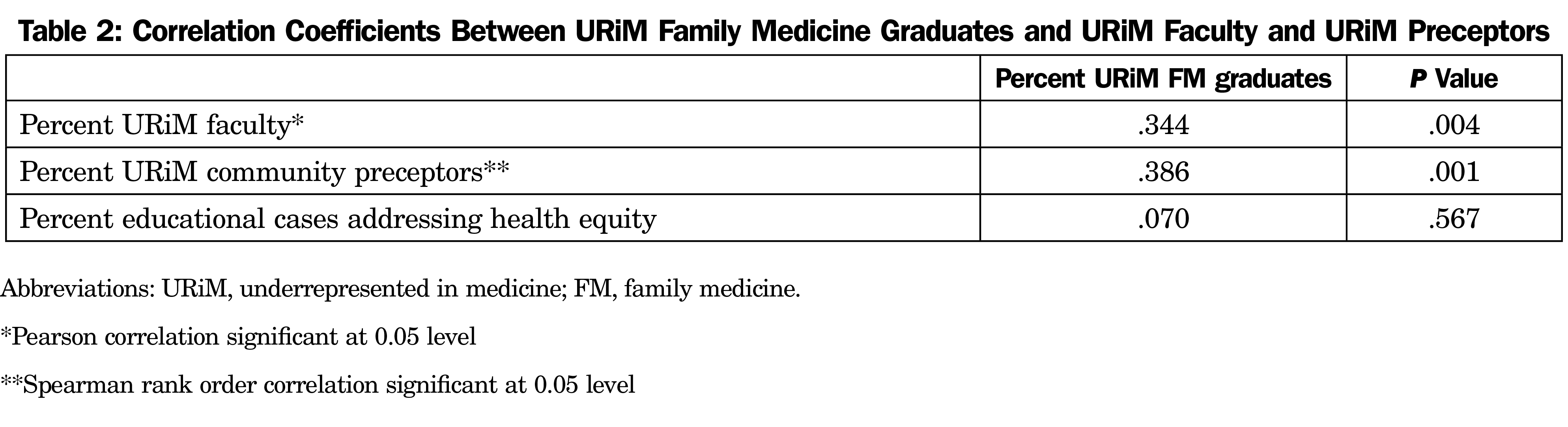

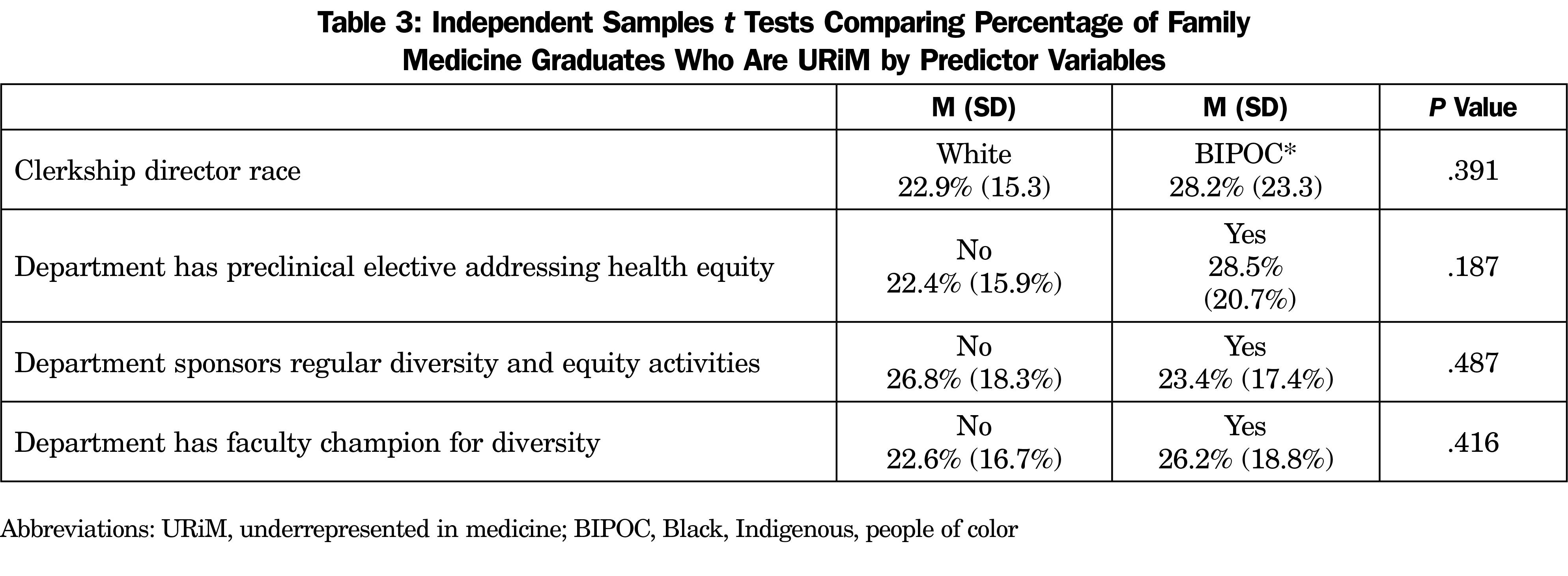

Results: Survey response rate was 49%. Two factors had a positive relationship with the percentage of graduating students who were URiM choosing family medicine residencies: having a higher percentage of faculty who were URiM (r=0.33, P=.004) and having a higher percentage of preceptors who are URiM (rs=.386, P=.001). We found no such association for having cases addressing health equity, offering preclinical electives, departments with a faculty champion for diversity, clerkship director race, or a department’s diversity activities.

Conclusions: The presence of teaching faculty and community preceptors from URiM backgrounds is correlated with the rate at which students who are URiM choose family medicine. People, rather than activities, seem to influence the career choices of students from URiM backgrounds.

A health care workforce that reflects the diversity of the community it serves is ideal for patient care. Over the past 30 years, the percentage of Black physicians in family medicine increased from 1.3% to 7.8% and the percentage of Hispanic/Latino physicians from 2.3% to 9.1%.1 However, the numbers of Black, Native American, and Hispanic/Latino family physicians remain underrepresented compared to the US population.2

When given a choice, patients tend to choose a physician of their own race, and having a same-race physician improves patient satisfaction.3 Racial/ethnic concordance between physician and patient improves communication,4 and may lead to better patient outcomes.5, 6 Patients were more likely to rate their physician highly if they were racially concordant with that physician.7 In addition, primary care physicians who are underrepresented in medicine (URiM) are more likely to practice in underserved areas.2 Although family medicine has proportionally more URiM physicians than the average of all specialties, we are still not representative of the general population.8

Growing a diverse family physician workforce is a long-term effort requiring a multifaceted approach. Improving the diversity of family medicine demands a sustained plan focusing on increasing the number of URiM students entering medical school; having URiM faculty, chairs, and mentors present; and having more URiM students choose residencies in family medicine. This paper examines how various clerkship and departmental factors may influence URiM medical students to choose family medicine residencies.

Survey

Data were gathered as part of the 2021 Council of Academic Family Medicine’s (CAFM) Educational Research Alliance (CERA) survey of family medicine clerkship directors9 which is an annual survey of clerkship directors at medical schools accredited by the Liaison Committee on Medical Education (LCME, US medical schools) or the Committee on Accreditation of Canadian Medical Schools (CACMS, Canadian medical schools). The final draft of survey questions was modified following pilot testing.

The survey was emailed to 147 US and 16 Canadian clerkship directors in April and May, 2021. Invitations to participate included a personalized letter signed by the presidents of the sponsoring organizations and a link to the survey via SurveyMonkey. Three US emails were undeliverable, resulting in 160 delivered invitations. Nonrespondents received three weekly requests, one final request 2 days before closing the survey, and a personal email. Five clerkship director changes were identified, and all new clerkship directors were invited to participate in the survey. The American Academy of Family Physicians Institutional Review Board approved the study in April, 2020.

Survey Questions

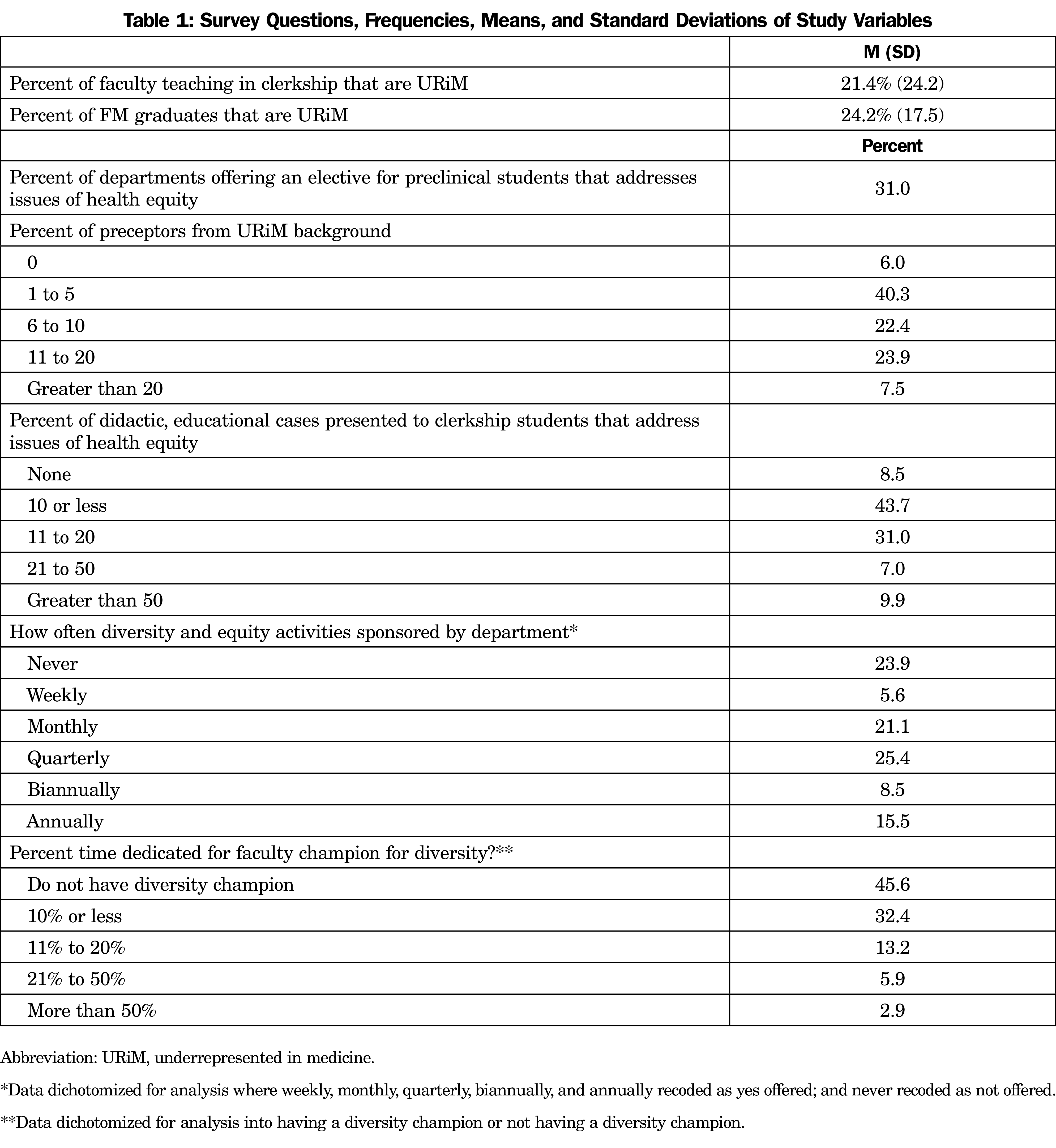

Participants answered questions about their medical school’s class size, family medicine graduates, and URiM status. They also answered questions about the number of URiM faculty, URiM preceptors, departmental faculty champion for diversity, clerkship educational cases addressing health equity, preclinical electives addressing health equity, and diversity and equity activities sponsored by their departments (Table 1).

Analyses

We summarized study variables using descriptive statistics. We calculated percent URiM faculty by dividing the number of faculty who teach in the didactic portion of the clerkship by the number of URiM faculty. We calculated the student variable for URiM status by dividing the average number graduating students who chose a family medicine residency, “family medicine graduates in the last 2 years by the number of family medicine graduates who were URiM averaged over the last 2 years.

Bivariate correlations determined associations between the percent URiM faculty (Pearson correlation), percent URiM preceptors, percent clerkship cases addressing health equity (Spearman rank order correlations), and the percent of URiM students choosing family medicine residencies. t tests determined associations between clerkship director race (White vs Black, Indigenous, People of Color), preclinical electives on health equity (yes vs no), department faculty champion for diversity (yes vs no), and department diversity activities (eg, faculty development, book club, invited lectures; yes vs no); and the percent of URiM students choosing family medicine residencies.

A total of 78 out of 160 clerkship directors (48.75% response rate) responded to the survey. Most respondents were female (56.8%), White (73.1%; 7.7% Black), and non-Hispanic or non-Latino (95.6%). Most clerkships (69.3%) were block only and were either 4 (36.5%) or 6 (26.9%) weeks long. Study variables are shown in Table 1. Correlations showed a positive relationship between both the percent of URiM faculty teaching in the family medicine clerkship and percent URiM preceptors with the percent of URiM students choosing family medicine residencies, but not for percent educational cases addressing health equity (Table 2). We found no associations between offering preclinical electives, departments with a faculty champion for diversity, clerkship director race, or a department’s diversity activities and the percent of URiM students choosing family medicine residencies (Table 3).

A greater number of URiM students chose family medicine residencies if their clerkships had more URiM faculty, or had more URiM family medicine community preceptors. The percent of family medicine clerkship cases addressing health equity, presence of departmental faculty champion for diversity, and existence of departmental diversity activities did not affect the rate of students choosing family medicine residencies. These interventions may have other important effects that were not found by this survey.

The study illuminates the importance of people rather than activities. The results of this study are similar to a study that demonstrated how mentoring positively impacted subspecialty choices by medical students.10 A study in orthopedics confirms that the presence of URiM orthopedic faculty is associated with a greater number of URiM students from that school applying to orthopedics.11 An additional study highlighted the lack of female and URiM role models and mentors as a barrier to diversity.12

Few studies have examined strategies to address increasing the rate of URiM students choosing family medicine residencies. One intervention focused on increasing outreach to URiM candidates, revising interviews to reduce bias, and reviewing recruitment data. After this intervention, the match rate for URiM students increased from 25% to 50%.13

One possible limitation of this study is the low response rate from the clerkship directors (48.75%.) Additional potential limitations include survey hesitancy or social desirability around the topic, and differences related to the geographic distribution of respondents. Due to space limitations, we were not able to inquire about these factors.

The future makeup of the family medicine workforce will depend upon current and ongoing efforts within departments and institutions. Our study calls attention to the importance of human capital in improving diversity in the family medicine workforce.

References

- Peabody MR, Eden AR, Douglas M, Phillips RL. Board certified family physician workforce: progress in racial and ethnic diversity. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(6):842-843. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.06.180129

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA. The racial and ethnic composition and distribution of primary care physicians. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2018;29(1):556-570. doi:10.1353/hpu.2018.0036

- Laveist TA, Nuru-Jeter A. Is doctor-patient race concordance associated with greater satisfaction with care? J Health Soc Behav. 2002;43(3):296-306. doi:10.2307/3090205

- Shen MJ, Peterson EB, Costas-Muñiz R, et al. The effects of race and racial concordance on patient-physician communication: a systematic review of the literature. J Racial Ethn Health Disparities. 2018;5(1):117-140. doi:10.1007/s40615-017-0350-4

- Charlot M, Santana MC, Chen CA, et al. Impact of patient and navigator race and language concordance on care after cancer screening abnormalities. Cancer. 2015;121(9):1477-1483. doi:10.1002/cncr.29221

- Field C, Caetano R. The role of ethnic matching between patient and provider on the effectiveness of brief alcohol interventions with Hispanics. Alcohol Clin Exp Res. 2010;34(2):262-271. doi:10.1111/j.1530-0277.2009.01089.x

- Takeshita J, Wang S, Loren AW, et al. Association of racial/ethnic and gender concordance between patients and physicians with patient experience ratings. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(11):e2024583. doi:10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.24583

- Xierali IM, Nivet MA, Gaglioti AH, Liaw WR, Bazemore AW. Increasing family medicine faculty diversity still lags population trends. J Am Board Fam Med. 2017;30(1):100-103. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160211

- Seehusen DA, Mainous AG III, Chessman AW. Creating a centralized infrastructure to facilitate medical education research. Ann Fam Med. 2018;16(3):257-260. doi:10.1370/afm.2228

- Yang Y, Li J, Wu X, et al. Factors influencing subspecialty choice among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open. 2019;9(3):e022097. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2018-022097

- Okike K, Phillips DP, Johnson WA, O’Connor MI. Orthopaedic faculty and resident racial/ethnic diversity is associated with the orthopaedic application rate among underrepresented minority medical students. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2020;28(6):241-247. doi:10.5435/JAAOS-D-19-00076

- Lightfoote JB, Deville C, Ma LD, Winkfield KM, Macura KJ. Diversity, inclusion, and representation: it is time to act. J Am Coll Radiol. 2016;13(12)(12 Pt A):1421-1425. doi:10.1016/j.jacr.2016.08.008

- Wusu MH, Tepperberg S, Weinberg JM, Saper RB. Matching our mission: a strategic plan to create a diverse family medicine residency. Fam Med. 2019;51(1):31-36. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2019.955445

There are no comments for this article.