Background and Objectives: The John Peter Smith (JPS) Family Medicine Residency Program participated in two national experiments: Preparing the Personal Physician for Practice (P4, 2007-2012) and the Length of Training Pilot, which began in 2013. In these experiments, JPS created optional integrated 4-year areas of emphasis (AOE). The objective of this study was to examine the career outcomes of JPS graduates differentiated by those who completed a 4-year AOE, versus traditional fourth-year fellowship, vs 3-year only.

Methods: We surveyed each graduate who started residency from 2007-2016 on their scope of practice. We also searched each graduate via Google to identify each of their practice sites and ascertain their status as a Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) or Medically Underserved Area for primary care (MUA-P).

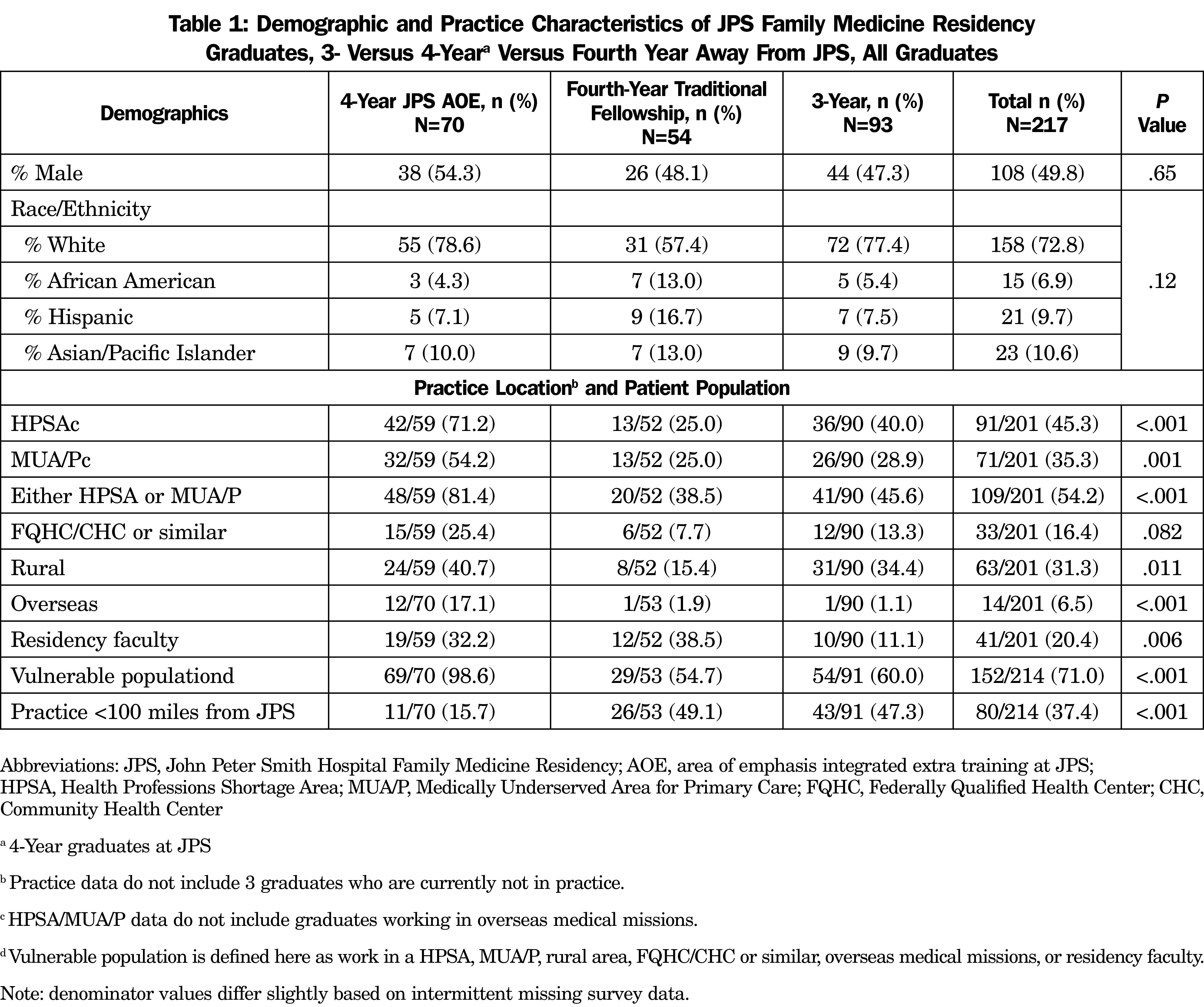

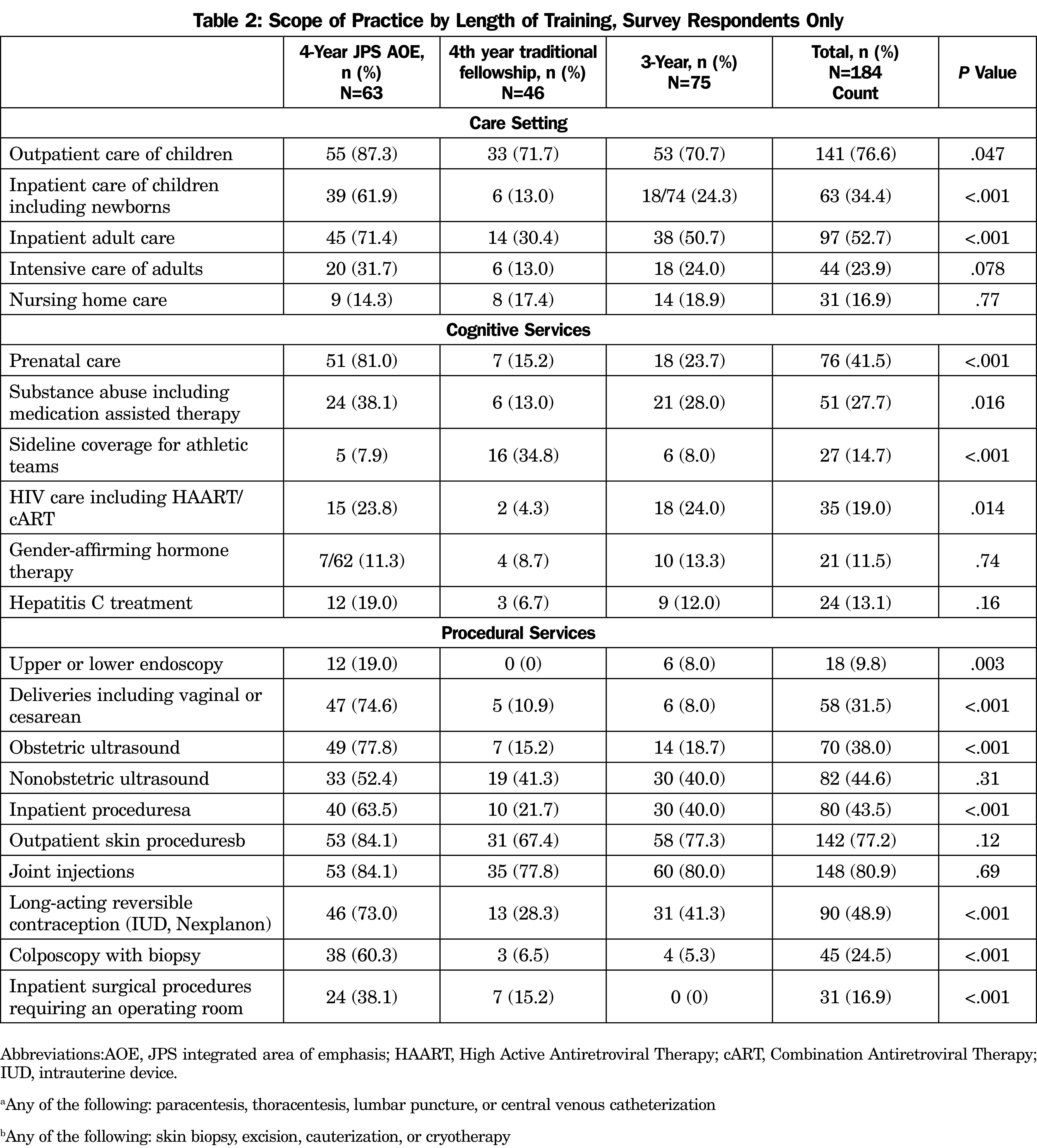

Results: Of the 220 residents who entered the program as interns, 70 completed an integrated AOE (31.8%), 54 completed 3 years of training with a traditional fourth-year fellowship (24.5%, 40 at JPS, 14 at another location), and 93 completed only 3 years of training (42.3%). The overall percentage of JPS graduates who work in the United States (n=201) in HPSAs or MUA-Ps is similar to national numbers (45.3% vs 43.5% for HPSAs, 35.3% vs 33.3% for MUA-Ps). Graduates of a JPS integrated AOE track were more likely to work in a HPSA or MUA-P than other graduates (81.4% vs 38.5% traditional fellowship vs 45.6% 3-year only, P<.001; US practice sites only). Graduates of sports medicine fellowships were particularly less likely to work in HPSAs/MUA-Ps than other graduates (26.1%). Graduates of integrated AOEs provided much broader scopes of cognitive and procedural services than fellowship or 3-year graduates.

Conclusions: In JPS graduates, 4 years of training with an integrated AOE had a large association with serving vulnerable populations, and providing broader cognitive and procedural services.

In 2007, the John Peter Smith (JPS) Family Medicine Residency joined the Preparing the Personal Physician for Practice project (P4).1,2 Given the freedom to innovate, JPS created a fourth-year option it described as flexible longitudinal tracks3 that allowed residents to pursue niche training in areas of interest (“areas of emphasis,” or AOE). Residents could choose a fourth year of training or to graduate after the traditional third year. In 2013, JPS joined the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education Length of Training (LoT) project, which is ongoing.4, 5 The most popular AOE tracks created included Maternal Child Health (MCH) and Advanced Rural/Global Medical Services (ARMS). Generally, residents pursuing a 4-year AOE formally apply to these tracks as second-year residents, but they can have some exposure to an AOE their first and second years. They spend an average of 6 months during both their third and fourth years pursuing rotations dedicated to their AOE training. We reported previously that the MCH AOE graduates were more likely to provide not only maternity care services, but also other advanced procedural services.6

The ARMS AOE was created out of the acknowledgement that the infrastructure to provide common general surgical procedures is lacking in much of the developing world,7 the lack of these services are a significant source of avoidable disability and death,8 and other countries have experimented with training their family physicians to provide common general surgical skills.9 JPS ARMS graduates receive training in procedures such as laparoscopic cholecystectomies, herniorrhaphies, appendectomies, large skin procedures including skin grafts, and others.

Other residents have completed 4-year AOEs in homeless and street medicine, hospital medicine, behavioral medicine, and adolescent medicine. Traditional fourth-year family medicine fellowships in sports medicine and geriatrics were available at JPS before P4 began and continue to be available. Some graduates chose traditional fourth-year fellowships at other institutions and graduated from JPS in 3 years.

Our aim was to examine whether graduates of JPS who completed 4 years of training in our integrated AOEs were more likely to practice in underserved communities, have a more advanced scope of practice, or provide a broader array of procedures than other graduate types. As the largest residency in the length-of-training project and the only to offer an optional fourth year, JPS offers a unique opportunity to serve as its own control group.

We surveyed graduates who matriculated at JPS from 2007-2016 by email or text message reminders. The survey instrument included elements of care locations (clinic, hospital, nursing homes, etc), procedures performed in both their initial and current jobs, reasons they did or did not work in certain locations or perform certain procedures, and whether they changed jobs since their first job out of residency. We used Likert scale responses to ascertain factors influencing their current scope of practice.

We used publicly available data from Google and Doximity to identify the practice location of each graduate who did not respond to the survey. We obtained practice locations of survey responders from survey data. We used the Health Professions Shortage Area lookup tool from the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) (https://data.hrsa.gov/tools/shortage-area/by-address) to determine if each of their practice locations were in a Health Professional Shortage Area (HPSA) or Medically Underserved Area for Primary Care (MUA-P). We received national HPSA and MUA-P data for family physicians from Stephanie Quinn at the American Academy of Family Physicians (AAFP). This classification for all graduates was determined in the summer of 2021, regardless of when they graduated.

We also examined if the graduates cared for vulnerable populations, which we defined as populations that either were in primary care physician shortage areas or were likely predominantly low income. These included graduates who practiced in HPSAs, MUA-Ps, rural locations, global mission facilities overseas, Federally Qualified Health Centers/Community Health Centers or similar, or family medicine residencies. We included family medicine residencies because they are much more likely to care for patients whose funding is Medicaid, indigent, or self-pay than family physicians in nonteaching settings.10 We defined rural practice as working in a zip code with a Rural-Urban Community Area (RUCA) code of 4 or greater.11

We analyzed data using SPSS version 23 (IBM, Inc, Armonk, NY). We used χ2 tests to evaluate relationships between curricular options, using a P value of <.05 to define statistical significance.

The Fort Worth Community Institutional Review Board determined that this was nonhuman subjects research and was exempt from further review.

Of the 220 residents who matriculated at JPS as PGY-1s between 2007 and 2016, 70 completed an integrated AOE (31.8%), 40 completed a fourth-year fellowship at JPS (18.2%, 24 sports, 16 geriatrics), 14 (6.4%) completed a fellowship outside of JPS (eight obstetrics, three geriatrics, one dermatology, one emergency medicine, and one sports medicine), 93 completed a 3-year residency (42.3%), and 3 (1.4%) did not graduate from JPS. See Table 1 for more demographic data of all JPS graduates. Two graduates came into the program as PGY2s and were not counted. Three graduates are currently not in practice.

Table 1 also shows the practice outcomes by HPSA, MUA-P, care for vulnerable populations, and their current worksite distance from JPS. Based on a National Provider Identifier-based study of 144,803 AAFP members, 43.5% (n=63,031) practice in a HPSA, 33.3% (n=48,275) practice in MUA-P, and 53.6% (n=77,671) practicing in a HPSA or MUA-P. Data for JPS graduates were 45.3% (n=91), 35.3% (n=71), and 54.2% (n=109), respectively overall, which are very similar to national numbers (JPS data do not include 13 graduates who are currently working overseas or who are soon leaving to go overseas, or three graduates not currently in practice).

The survey response rate was 84.8% (n=184) but current practice location was determined even for those who did not respond to the survey. Four-year AOE graduates were more likely than fourth-year fellowship or 3-year-only graduates to work in the rural United States (40.7% [n=24] vs 15.4% [n=8] vs 34.4% [n=31], P<.011), overseas (17.1% [n=12] vs 1.9% [n=1] vs 1.1% [n=1], P<.001), and care for a vulnerable population (98.6% [n=69] vs 54.7% [n=29] vs 59.3% [n=54], P<.001). AOE and fourth-year fellowship graduates were more likely to work at a family medicine residency as faculty (32.2% [n=19] vs 38.5% [n=12] vs 11.1% [n=10], P=.006; Table 1). If the graduates who were classified as caring for vulnerable populations only by their academic job status are removed from that designation, the results become 92.9% (n=65), 49.1% (n=26), and 57.1% (n=52, P<.001).

There were many differences between AOE, 4-year fellowship, and 3-year graduates on the cognitive and procedural services they provide (Table 2). AOE graduates were more likely to work in nonclinic facilities such as hospitals, provide cognitive services such as prenatal care and substance abuse care, and perform a wide array of procedures, particularly procedures related to women’s health and hospital care.

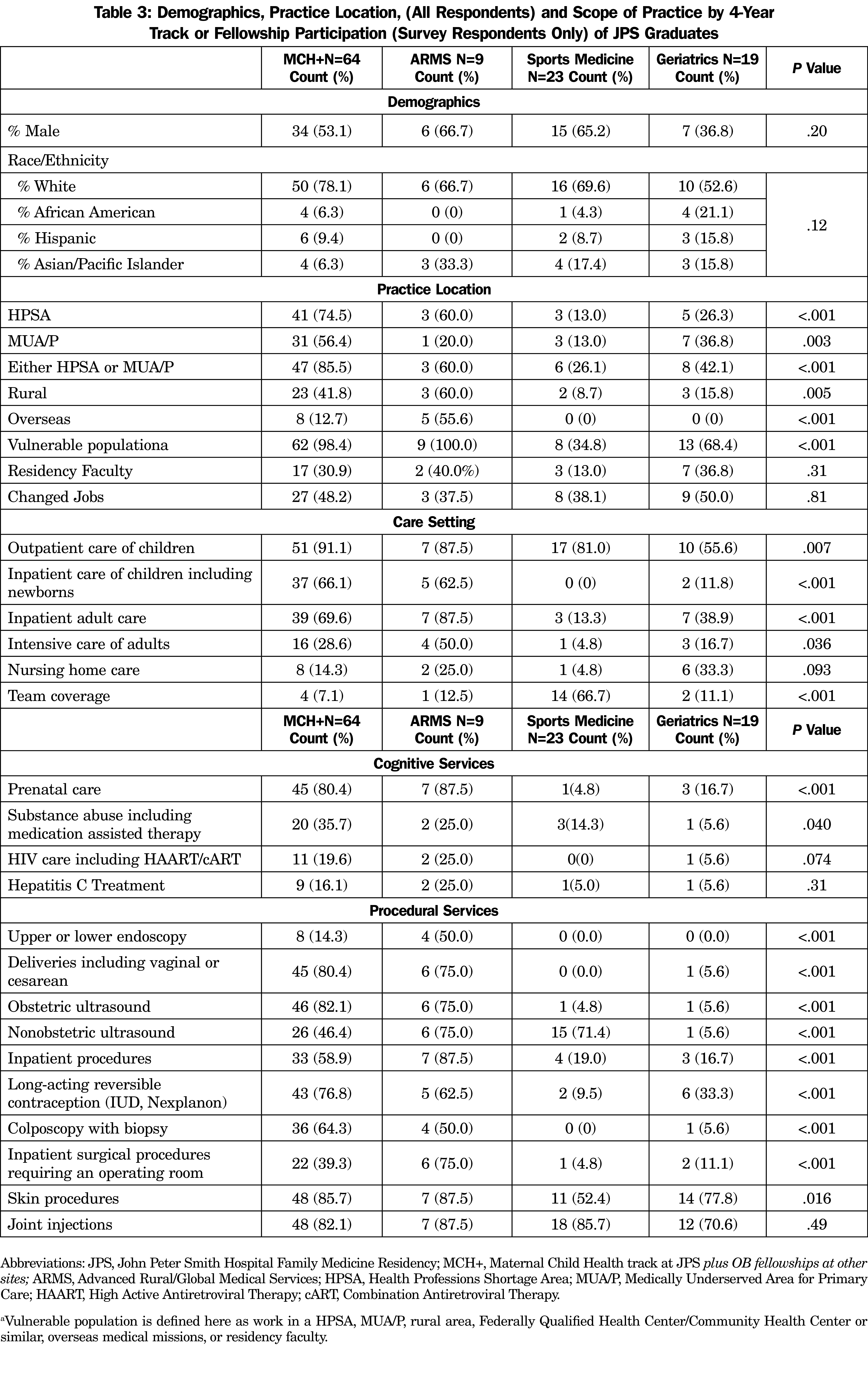

The much greater difference in practice scope is the provision of comprehensive cognitive and procedural services that become apparent when comparing the subsets of 4-year training options (Table 3). Those who completed the MCH AOE (or a non-JPS OB fellowship) or ARMS AOE and practice in the United States were more likely than those who completed geriatrics or sports fellowships to serve in HPSAs or MUA/Ps (for either a HPSA or MUA/P: MCH 85.5% [n=47], ARMS 60.0% [n=3], sports medicine 26.1% [n=6] and geriatrics 40.0% [n=8], P<.001), and serve vulnerable populations (MCH 98.4% [n=62], ARMS 100.0% [n=9], sports medicine 34.8% [n=8]), and geriatrics 65.0% (n=13, P<.001). There was also a marked difference between the MCH and ARMS tracks vs sports and geriatrics in almost every practice location, cognitive service, and procedural service we measured.

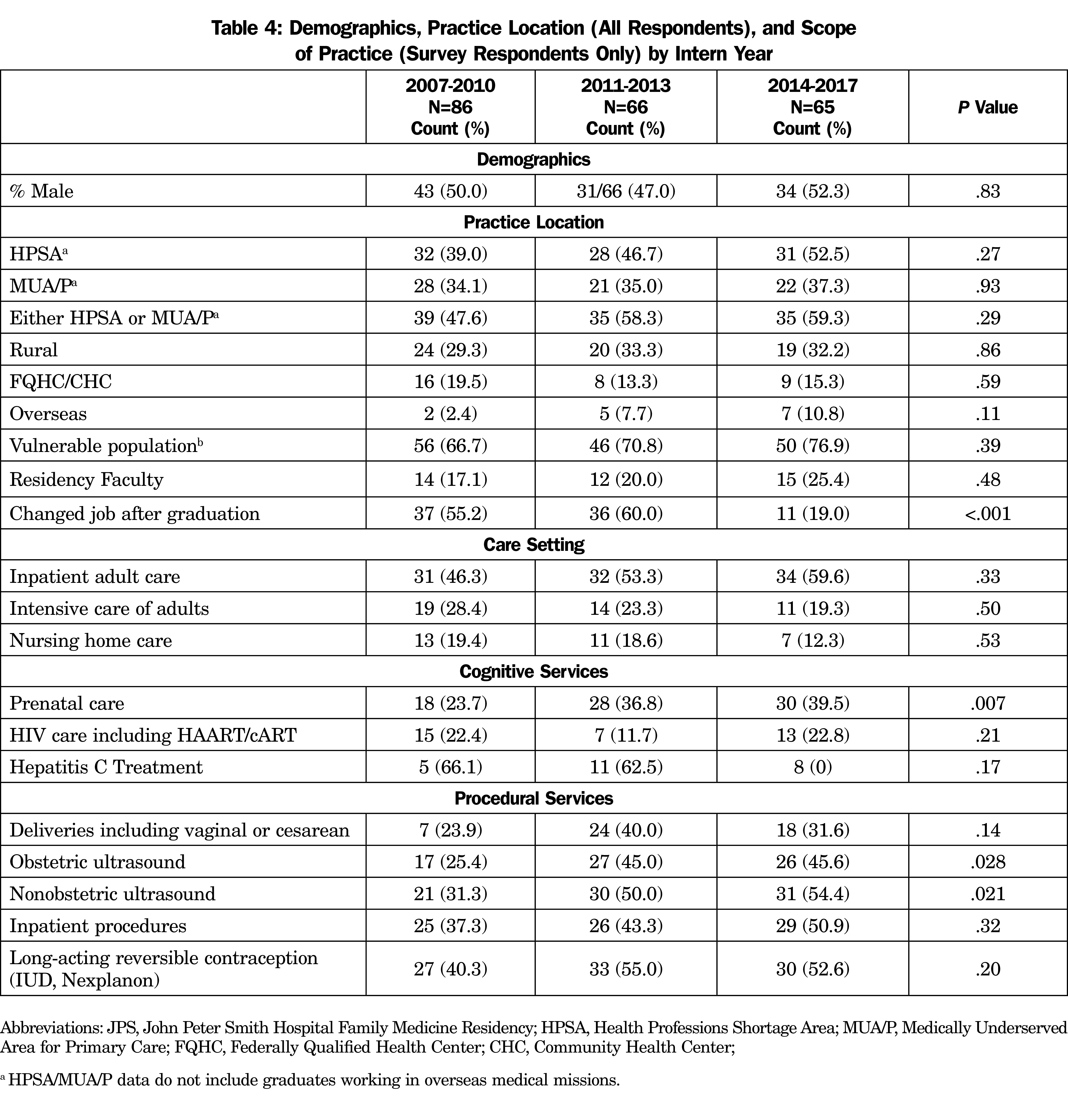

We grouped graduates into 3- to 4-year intern year graduation blocks to look for time effects (2007-10, 2011-13, 2014-16; Table 4). There were very few differences overall. Notably, more than half the graduates in the earlier two blocks had changed jobs from their first job after graduation (55.2% [n=37] vs 60.0% [n=36] vs 19.0% [n=11], P<.001). There were fewer graduates from the earliest block providing prenatal care, OB ultrasound, and non-OB ultrasound than the latter two blocks.

We found that the answer to the question, “Is a fourth year of FM training associated with graduates caring for different patient populations and providing more comprehensive services?” is “It depends.” Overall, JPS graduates worked in similar percentages of HPSAs and MUA-Ps as family physicians nationally. The marked difference came in graduates with integrated AOE training, who were much more likely to provide a broad array of cognitive and procedural services to vulnerable populations in HPSAs and MUA/Ps. The traditional sports and geriatrics fellowship graduates were less likely to provide these services or work in these locations than even the 3-year graduates.

This study was not designed to answer the important question of whygraduates of different curricular tracks have different services and locations outcomes. We hypothesize that traditional fellowship graduates spend a year solely focused on their area of emphasis, often moving away from the practice of broad-spectrum family medicine entirely during this year. This may better prepare them for specialty practice and discourage them from choosing a job practicing the full spectrum of family medicine. Four-year AOE residents continue to practice and learn full-spectrum family medicine across their entire length of training, becoming more accustomed to their AOE being “one thing they do particularly well” rather than the whole focus of their eventual practice.

There is also a chicken-and-egg nature to our findings. While the MCH and ARMS training may inspire some residents to practice differently than other graduates, it is also likely that some of our graduates entered JPS wanting to provide a very comprehensive array of cognitive and procedural services in their careers, and knew that there were certain underserved practice environments where that was most likely to occur.

There are very few family physicians in the United States living in higher-resource settings who deliver babies, and especially who perform Cesarean delivery in those settings. Family physicians are much more likely to be granted privileges to perform those procedures in rural hospitals, especially the smaller ones.12, 13 A noticeable minority of our MCH graduates became FM residency faculty, which is an exception to the pattern that family physicians more typically provide maternity services in rural settings, but is consistent with a previous study of graduates of OB fellowships.12

Our results also likely reflect the realities of patient catchment volumes required to supply a practice. Many of our sports medicine graduates only provide musculoskeletal care. Therefore, a large patient population is required to generate enough specialty referrals. Similarly for graduates who only desire to care for an elderly population, it should be large enough to support several nursing homes and skilled nursing units.

These findings are similar to an earlier study examining only the JPS MCH AOE.6 MCH graduates were not only more likely to provide maternity care services, but also care of children and other hospital-based services. We continue to find that on the whole, JPS graduates were more likely to provide a broader array of cognitive and procedural services than those reported by the P4 initiative and other surveys by the American Board of Family Medicine on practicing family physicians nationally.14-18 This study adds to previous research on MCH graduates and now adds the early outcomes of ARMS graduates and other AOEs, including street medicine. The ARMS graduates are even more likely to care for vulnerable populations in a wide variety of care settings, and provide a comprehensive array of cognitive and procedural services.

Our study was limited to one institution. Some of what has been created at JPS may be difficult to replicate at other programs, particularly smaller residencies. Our response rate of 84% implies that it is unlikely that our results would change significantly if we had full participation. Our reporting of 13 graduates currently (or soon to be) working overseas does not include three graduates who spent several years overseas, but who are now back in the United States working as residency faculty. Because only eight graduates completed traditional OB fellowships away from JPS, we cannot comment on the differences in graduate outcomes between those graduates and JPS MCH AOE graduates.

There were relatively few temporal changes. For this report, we only looked at current practice patterns, therefore we cannot be sure if, for example, the slightly lower percentage of graduates from the earliest cohort providing maternity-related services is because they never provided those services, or they did early in their career, then stopped providing them. We will report in a subsequent study a mixed methods, deeper dive into this and other scope-of-practice findings. The fact that over half of the graduates who had been in practice more than 3 years changed their jobs has implications for future research about the connection between residency education and career outcomes. Our findings emphasize that graduates’ first job out of residency will not necessarily be their lifelong job.

Other researchers have identified the larger health care landscape as an influence on the scope of practice of rural family physicians.19 Future research should further explore the effects of these forces vs individual preferences on the scopes of practice of individual family physicians.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest: Dr Richard Young discloses that he is the sole owner of SENTIRE, LLC, which is a primary care documentation, coding, and billing system. The other authors report no conflicts.

Funding Statement: Some funding was provided by the steering committees from the P4 and ACGME Length-of-Training Pilot experiments

References

- Green LA, Jones SM, Fetter G Jr, Pugno PA. Preparing the personal physician for practice: changing family medicine residency training to enable new model practice. Acad Med. 2007;82(12):1220-1227. doi:10.1097/ACM.0b013e318159d070

- Carney PA, Eiff MP, Waller E, Jones SM, Green LA. Redesigning residency training: summary findings from the Preparing the Personal Physician for Practice (P4) Project. Fam Med. 2018;50(7):503-517. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.829131

- LoPresti L, Young R, Douglass A. Learner-directed intentional diversification: the experience of three P4 programs. Fam Med. 2011;43(2):114-116.

- Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical E. Second Call for Proposals. Family Medicine Length of Training Pilot. 2012. Accessed April 16, 2015. https://www.acgme.org/acgmeweb/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramResources/120_LoT_Second_Call_for_Proposals.pdf

- Carek PJ. The length of training pilot: does anyone really know what time it takes? Fam Med. 2013;45(3):171-172.

- Young RA, Casey D, Singer D, Waller E, Carney PA. Early career outcomes of family medicine residency graduates exposed to innovative flexible longitudinal tracks. Fam Med. 2017;49(5):353-360.

- Farmer PE, Kim JY. Surgery and global health: a view from beyond the OR. World J Surg. 2008;32(4):533-536. doi:10.1007/s00268-008-9525-9

- Debas HT. The emergence and future of global surgery in the United States. JAMA Surg. 2015;150(9):833-834. doi:10.1001/jamasurg.2015.0898

- Kim EE, Araujo D, Dahlman B, et al. Delivery of essential surgery by family physicians. Bull World Health Organ. 2020;98(11):766-772. doi:10.2471/BLT.20.252056

- Texas Academy of Family Physicians. Family Medicine Residency Programs Are Critical in Training Texas’ Physician Workforce. Accessed March 7, 2022. https://www.tafp.org/Media/Default/Downloads/advocacy/Support_FM_Residency_Expansion.pdf

- Rural-Urban Continuum Codes. USDA Economic Research Service. Updated December 10, 2020. Accessed June 29, 2022. https://www.ers.usda.gov/data-products/rural-urban-continuum-codes.aspx

- Chang Pecci C, Leeman L, Wilkinson J. Family medicine obstetrics fellowship graduates: training and post-fellowship experience. Fam Med. 2008;40(5):326-332.

- Young RA. Maternity care services provided by family physicians in rural hospitals. J Am Board Fam Med. 1/2 2017;30(1):71-77. . doi:10.3122/jabfm.2017.01.160072

- Bazemore AW, Makaroff LA, Puffer JC, et al. Declining numbers of family physicians are caring for children. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(2):139-140. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2012.02.110203

- Bazemore AW, Petterson S, Johnson N, et al. What services do family physicians provide in a time of primary care transition? J Am Board Fam Med. 2011;24(6):635-636. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2011.06.110171

- Peterson LE, Fang B, Puffer JC, Bazemore AW. Wide gap between preparation and scope of practice of early career family physicians. J Am Board Fam Med. 2018;31(2):181-182. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2018.02.170359

- Tong ST, Makaroff LA, Xierali IM, et al. Proportion of family physicians providing maternity care continues to decline. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(3):270-271. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2012.03.110256

- Xierali IM, Puffer JC, Tong ST, Bazemore AW, Green LA. The percentage of family physicians attending to women’s gender-specific health needs is declining. J Am Board Fam Med. 2012;25(4):406-407. doi:10.3122/jabfm.2012.04.110290

- Reitz R, Horst K, Davenport M, Klemmetsen S, Clark M. Factors influencing family physician scope of practice: a grounded theory study. Fam Med. 2018;50(4):269-274. doi:10.22454/FamMed.2018.602663

There are no comments for this article.