We agree with the article by authors Koonce and colleagues, who highlight the importance of incorporating veteran-specific occupational and health questions through case discussions during first-year medical education.1 As health professionals who have served in the military and/or cared for veterans at US Veterans Health Administration (VHA) and non-VHA health facilities, we understand firsthand that military service and deployments embody a significant part of veterans’ identity.2 Following the deployments since 9/11, many veterans have received physical and mental health diagnoses as a result of environmental and occupational exposures.3 The postdeployment reintegration period is defined as 3 to 6 months or longer following a veteran’s return home from deployment. With limited veteran-specific content on mental health topics in health professions education,4-5 family medicine educators can lead efforts to develop short-term learning experiences for medical students and residents that offer guidance on the prompt diagnosis and management of veterans’ mental health during their postdeployment transitions.

The VHA has prioritized veterans’ mental health services for postdeployment needs with increased annual funding to $8.9 billion, expanded telehealth visits for veterans, and other actions to enhance access to mental health services.6 Alarming statistics highlight the reported suicide rate of 17.2 veterans per day,7 and link combat deployment to increased risk of mental health diagnoses like posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD), suicide, and depression.8 Although emotional disturbances may result from combat stressors as reported by the Millenium Cohort Study8 (eg, repeated post-9/11 deployments, postdeployment reintegration challenges), rapidly withdrawing service members from Afghanistan and leaving some Afghan translators in the country9 may have exacerbated feelings of anxiety, powerlessness, shame, or regret. These combined stressors can significantly impact veterans’ and family members’ mental health and well-being needs during the postdeployment transition period.

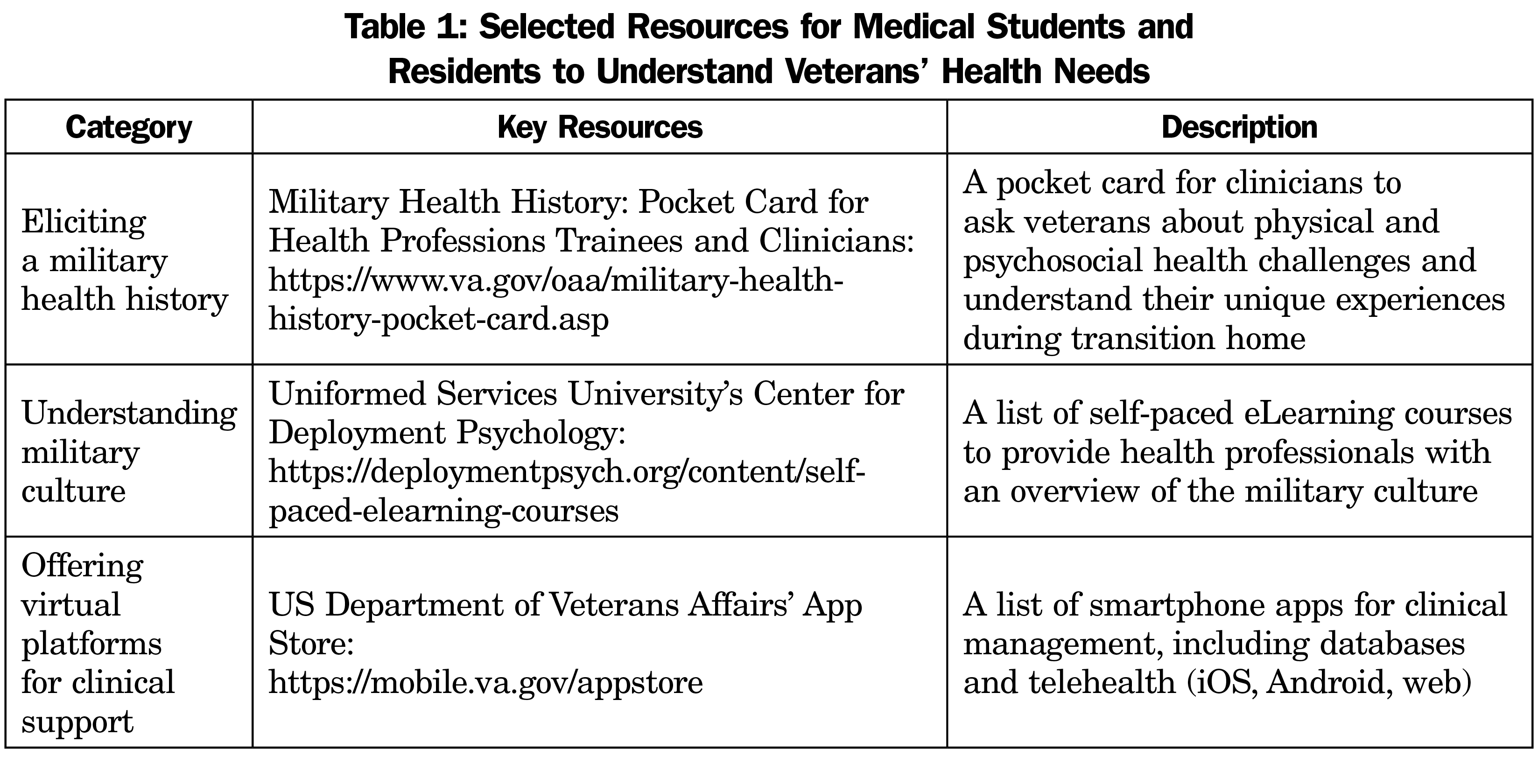

To address this mental health burden, family medicine educators can streamline clinical questioning to elicit veterans’ specific, postdeployment health concerns. First questions should always include: Are you a veteran? What was your service and specialty? Were you deployed overseas? When did you return from deployment? These questions should be followed by recognition of their selfless service.2 Service members are a heterogenous population, with differences in biological (eg, age, ethnicity, gender), sociodemographic (eg, economic status, education, residence), and military (eg, service branches, service components, service era) information. Service members may represent active duty (full-time) or Reserve and National Guard (part-time) forces, with distinct postdeployment transition needs that can influence health-seeking behaviors at VHA and non-VHA health facilities.2 Understanding these individual veterans’ health needs can ultimately enhance doctor-veteran rapport and build trust in shared decision-making activities for optimal mental health service delivery. Short-term courses and workshops that incorporate role-playing exercises, case studies, invited lectures with veterans, and roundtable discussions offer practical opportunities for medical trainees to utilize innovative tools and master clinical skills addressing postdeployment reintegration needs (Table 1).3

As primary care practitioners, serving our nation’s veterans at VHA and non-VHA health facilities is our utmost duty. By better understanding veterans’ invisible wounds, we can identify relevant resources that support their mental health needs as they transition from deployment to civilian life.

There are no comments for this article.